Joe Evans

Joseph Patton Evans was born on May 15, 1895, in Meridian, Mississippi, the fourth of nine children born to Albert and Ida Evans. Albert supported his family by working as an engineer on a locomotive.1

Joseph Patton Evans was born on May 15, 1895, in Meridian, Mississippi, the fourth of nine children born to Albert and Ida Evans. Albert supported his family by working as an engineer on a locomotive.1

Eventually a 5’9”, 146-pound man, Joe Evans was given the name “Little Joe” by his classmates much earlier. In truth, there was nothing “little” about his exploits on the athletic field, or in the classroom; he excelled in both. After he graduated from Meridian High School, Evans enrolled at the University of Mississippi. Despite his stature, he was the star quarterback on the football team. In a game against Arkansas in 1914, Evan’s 20-yard touchdown run in third quarter was the final margin in the Rebels’ 13-7 win. The Jackson Daily News noted that Evans’s “end runs are the feature of every game in which he participates.”2

The Ole Miss baseball team had a special instructor as it prepared for the 1914 season. Casey Stengel, an outfielder for the Brooklyn Superbas, came to Mississippi to try his hand at coaching. His former high school coach, Bill Driver, was now at Ole Miss and invited Stengel to camp, and by most accounts Stengel worked well with the players before he headed off to spring training with Brooklyn. The team presented Stengel with a gold-handled cane as a token of their appreciation for his tutelage. “Yes sir, when they call me the ‘professor’, they ain’t kidding. There’s a good reason,” said Stengel.3

On the baseball field, Evans played third base and his batting averaged hovered around .450 in 1914. Ole Miss won the state baseball championship, and Evans played a key role their success. During the summer of 1914, he played for a semipro baseball team, which made him ineligible to play any longer with the Rebels. But his play on the diamond had drawn the interest of local and national scouts, and even though he was prohibited from suiting up for the Rebels in 1915, the Cleveland Indians signed him. Evans was a rarity in those days: few players in the major leagues were college educated then. Many never finished high school or grammar school.

Charles Somers not only owned the Indians but he also owned Cleveland’s entry in the Double-A American Association, the Cleveland Spiders. And that’s where Evans began the 1915 season. In an article in the Cleveland Plain Dealer, Evans was reported as one of the more well-liked players on the Spiders roster. “He is now about the most popular player on the team. Not because he is a great batter, because he is only hitting .235. It is not because of his all-around fielding ability because no Spider makes more errors than he. Why is it then? Because he is the livest wire among the many live wires on the Spider payroll. He goes down to first base like a shot and is probably the fastest runner in the A.A. He is a good man on grounders, but rather weak on thrown balls.”4 Evans Idid most of his playing with the Spiders that season, batting .259 in 55 games. Playing third base, Evans fielded his position at a .917 clip.5

Evans joined the Indians on June 26 as infielder Roy Wood was sent to the Spiders. He made his major league debut on July 3, 1915, at Sportsman’s Park. On the hill for the opposition St. Louis Browns was none other than George Sisler, the future Hall of Fame first baseman. He was also in his rookie year, and like Evans was a college man who had attended the University of Michigan. Officially, Evans went 0 for 0 at the plate, walking twice. In his rookie season, Evans got 109 at-bats in 42 games and hit for a .257 average.

But the Indians were in turmoil in 1915. Somers was facing financial ruin. Cleveland, which finished in in the upper division, third place in 1913, dropped to dead last in 1914. The following year, they won just a paltry 57 games and finished seventh. The team’s sour fortunes brought a sea of empty seats to League Park. Among other unpopular moves Somers made was to cut ties with Nap Lajoie and his $9,000 yearly salary. Lajoie had been in Cleveland for 13 seasons and was a popular player, not to mention one of the greatest players of all time.

The Federal League came to being in 1914, and the ownership of those teams were offering sweetheart deals in an attempt to lure the major league talent over to the new league. Rumor had it that one of Cleveland’s star players, Joe Jackson, had been offered a yearly salary of $10,000 by one team. Jackson was receiving $6,000 a year from Cleveland, and Somers feared losing him without any compensation. After receiving multiple offers, Somers sent Jackson to the Chicago White Sox on August 21, 1915. in exchange for outfielder Braggo Roth, pitcher Ed Klepfer, and $31,500. Pitcher Larry Chappell arrived on February 14, 1916 to complete the deal.

But the influx of cash had not been sufficient. It was critical to American League President Ban Johnson to have a team located in Cleveland, the sixth largest city in the United States. When his attempts to find viable ownership in Cleveland failed, Johnson widened his search to find his man. The team was sold to Chicago businessman Jim Dunn before the 1916 season.

Dunn made his mark early on. Tris Speaker, who was coming off a year where he hit .322 with the Boston Red Sox, was in a contract stalemate and refused to report to the Red Sox. Boston had won the World Series in 1915, their second one in four years. On April 9, 1916, Speaker was sent to the Indians for pitcher Sad Sam Jones, infielder Fred Thomas, and $55,000 cash. Speaker was not particularly pleased. “If you want to continue in the big show you must go where the owners send you,” he said. “I hate to leave Boston, for I like the people here. I have never played big league ball for any other team than the Red Sox.”6

Cleveland allowed Evans to report to spring training late the following season. He returned to Mississippi to complete his studies toward a medical degree. He broke camp with the Tribe, but Evans was farmed out to Class AA Portland of the Pacific Coast League.

The following spring Cleveland manager Lee Fohl named Evans the starting third baseman for the 1917 season. Evans started 124 games at the hot corner, committing 27 errors and fielding his position at a .939 clip. And although he did hit Cleveland’s first home run of the season on May 17 against Boston, his offensive numbers were horrendous. With an anemic slash line of .190/.271/.242, he amassed only 33 RBI and practically forfeited his chances of being a starter again. But the Cleveland team itself was on the upswing, having finished in third place in the AL, 12 games behind Chicago.

Like many players around the league, Evans’s draft board was pressing to have him serve his country during World War I. Evans and other draftees who were medical students received special dispensation to continue work towards completing their degree. When Evans reported to Camp Pike in Little Rock, Arkansas, he was sent home to complete his medical degree at Ole Miss. Evans agreed to stay in school until completion of the spring semester and leave the team early for the beginning of the fall semester. As it turned out, many players were being called to active duty, and the baseball season was cut short in 1918 to accommodate the war effort. The regular season ended on Labor Day, and the World Series was moved up as well.

Evans did not join the Indians until the end of May, making his season debut on May 29 against Detroit. The lack of spring training did not seem to affect him, as he tripled in a run in the second inning; he also singled and scored in the fourth frame as the Indians beat Detroit 7-1. Apparently Evans saved his best games for the Tigers. On July 1 at League Park, he opened the bottom of the seventh inning with a triple over Ty Cobb’s head in center field. He scored when Detroit catcher Archie Yelle dropped the relay throw from Bobby Veach. Evans also figured in two double plays, one unassisted, to help Fritz Coumbe win his ninth victory.

Evans raised his batting average to .263 in 1918, a terrific improvement. However, his days at third base were over. The bothersome Braggo Roth, who often clashed with Fohl, was traded in the off-season to Philadelphia for outfielder Charlie Jamieson, third baseman Larry Gardner, and pitcher Elmer Myers. It was one of the great trades in Indians history as Jamieson and Gardner would prove to be cornerstones of future Indians teams. Gardner was a terrific third baseman who was a teammate of Speaker’s in Boston, and doubtless Tris pushed for his acquisition. An article in the Cleveland Plain Dealer on January 17 indicated that Evans was initially involved in the trade talks with the Athletics, but he ended up staying put.

With Gardner’s arrival, Evans was moved to an already-crowded Tribe outfield. Speaker, Jamieson, Jack Graney, Smoky Joe Wood, and Elmer Smith were going to see plenty of action. Speaker took over for Fohl as the Indians manager on July 19 and then led the team to a 40-21 record for the balance of the season. The Tribe finished a mere 3½ games behind Chicago.

During the 1919 season Speaker used a platoon system to get his surplus of outfielders into ballgames. Jamieson, Smith, and Graney hit left-handed while Wood and Evans batted from the right side of the plate. Evans had more than enough speed and agility to cover left field. Cleveland employed the platoon system again in 1920 with either Jamieson or Evans manning left field. It worked to perfection as Evans batted .349 in 56 games, and Jamieson .319. On May 29 in the first game of a doubleheader against the White Sox, Evans went 2 for 4 with two doubles, an RBI, and a run. Both two-baggers came off southpaw Claude Williams. Three days later on June 1, Evans collected three doubles, a career high, against Detroit lefty Red Oldham. Dr. Joe also scored two runs and drove in a run.

Evans, who had earned the nickname “Doc” from his teammates in years past, was now being referred to as “Dr. Joe” or “Dr. Evans” in some game stories. Unfortunately, the doc got sick himself during the season: he ate some contaminated food and became violently ill with ptomaine poisoning. He was sidelined from July 15 through August 22.

The 1920 baseball season was historic in several ways. First, Babe Ruth was in his first year with the Yankees, and his tremendous home runs were drawing fans to the ballpark in droves. Coming on the heels of the deadball era where home runs were a relative rarity, the constant barrage of Ruth’s round-trippers polarized the sport. Many newspapers gave daily updates on Ruth’s progress as he marched to an unheard of 54 home runs in 1920.

The 1920 season also witnessed the death of Cleveland shortstop Ray Chapman on August 17, 1920, the first and still only player to be killed by a pitched ball. The day before, Chapman had been struck in the head by a pitch from Yankee pitcher Carl Mays. The sidewinder Mays had a reputation for hitting batters, which compounded the situation as many speculated he threw the pitch intentionally. But it had been a gray, misty, and foggy day at the Polo Grounds, and most suspect that Chapman just didn’t pick up the pitch in time. “Chappie” as he was called was not only a great shortstop but was popular with his teammates and opponents alike.

Finally the news of the eight “Black Sox” players who had colluded with gamblers to throw the 1919 World Series reached all corners of the country the following September. Chicago owner Charles Comiskey immediately suspended all of them, putting his team’s chances of repeating for a pennant in peril. Indeed, the White Sox lost two of their last three games after the suspensions, and Cleveland closed the year winning four of six to win their first pennant. They would face off against the Brooklyn Robins in the World Series.

Cleveland’s excellent pitching staff was led by Jim Bagby, who went 31-12 with a 2.89 ERA. He was followed by Stan Coveleski (24-14, 2.49) and Ray Caldwell (20-10, 3.86). Coveleski led the AL in strikeouts with 133.The Indians were also a solid hitting club with Speaker leading the way batting .388 and a league best 50 doubles. Gardner hit .310 and led the team in RBI with 118. Chapman had been hitting .303 before his untimely death. It seemed impossible that he could be replaced, but Joe Sewell stepped in and batted .329 in 22 games.

Evans gave a good account of himself in the Fall Classic. As in the regular season, Evans was in the starting lineup against Brooklyn’s southpaw hurlers, Rube Marquard and Sherry Smith. He batted .308, and going 3 for 4 in Game Six. However, he was picked off first base by Smith after his third safety in the eighth inning.

Cleveland won its first World Championship in seven games. As expected, the entire city went into a jubilant and celebratory mood. After the season, Evans went to St. Louis—where he had completed his medical degree at Washington University— to work in a hospital for his residency.

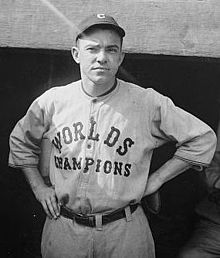

Once again platooned, Evans had another splendid year in 1921; facing mostly left-handed pitching, he batted .333. He also set his own career highs for hits in a game with four on two occasions. The first was against the Tigers on April 26, and he then again on September 15 against the Athletics. The Indians had “Worlds Champions” emblazoned across their uniform tops in 1921. However, they could not give the Cleveland fans an encore; they finished second, 4½ games behind New York in 1921.

Following the 1922 season, Evans decided to hang up his cleats and focus on his medical practice. However, when Senators owner Clark Griffith made it known that he would like Evans to man third base, Doc relented. Playing the hot corner was his favorite position, so he was dealt to Washington for outfielder-first baseman Frank Brower on January 8, 1923.

Offensively, the Senators were loaded. Joe Judge, Muddy Ruel, Nemo Leibold, Sam Rice, and Goose Goslin all batted over .300. Evans managed a .263 average in 106 games, the most action he had seen since the 1917 season. He also set career marks in hits (98), doubles (15), RBI (38) and runs (42). The Senators finished a distant fourth in 1923. But they had laid a strong foundation that would win back-to-back AL pennants in 1924 and 1925.

Unfortunately for Evans, he had moved on and didn’t share in the glory. He was now playing as a spare outfielder for the St. Louis Browns, and he retired for good after the 1925 season. Over the course of 11 seasons, Evans batted .259 with three home runs and 210 RBI. He also totaled 71 doubles and 31 triples. In 1927, Evans tried his hand as a minor league manager, taking the reins of the Class D Gulfport Tarpons of the Cotton State League. But he managed only one season.

In retirement, Dr. Joe Evans returned to his home state of Mississippi. He set up practice as an obstetrician in Gulfport. Evans passed away on August 8, 1953 at his home after a year-long battle with esophageal cancer.7 He was survived by a wife and daughter.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Tom Schott and fact-checked by Alan Cohen.

Notes

1 1910 United States Census

2 “Mississippi Downs Arkansas Eleven”, Jackson Daily News, November 14, 1914: 4.

3 Scott H. Longert, The Best They Could Be, (Potomac Books, Washington D.C., 2013), 58.

4 “Dixie Youth Makes Hit With Spider Fans”, Cleveland Plain Dealer, June 13, 1915: 1C.

5 Joe Evans Player File, Baseball Hall of Fame, Cooperstown, New York.

6 Scott H. Longert, The Best They Could Be (Dulles, Virginia: Potomac Books, 2013), 27-28.

7 Some sources have Evans death occurring on August 9, 1953. But according to the death certificate and the photo of his grave on the Baseball Necrology, August 8, 1953 is correct.

Full Name

Joseph Patton Evans

Born

May 15, 1895 at Meridian, MS (USA)

Died

August 9, 1953 at Gulfport, MS (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.