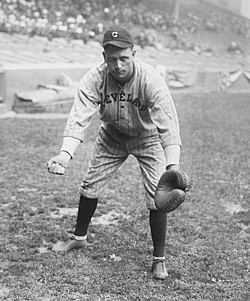

John Peters

During the Deadball Era, physical size was considered a huge asset for a catcher. A big man was thought to be better able to withstand the physical demands of the position and thus be more durable than a smaller man. The success of Detroit’s Charlie “Boss” Schmidt (5’11”, 200 pounds) was probably one of the reasons the Tigers gave another big catcher, John Peters, a look. His Baseball-Reference page lists him at an even six feet and 192 pounds, but many contemporary reports said that Peters was either 6-foot-2 or 6-foot-3 and weighed over 200 pounds. He picked up the nicknames “Big Pete,” “Big John,” “Long John,” and even “Moose.” However, despite his physical attributes and a respectable .265 career batting average in the big leagues, a strong but erratic throwing arm (which led to another nickname, “Shotgun”) limited Peters to just parts of four major league seasons.

During the Deadball Era, physical size was considered a huge asset for a catcher. A big man was thought to be better able to withstand the physical demands of the position and thus be more durable than a smaller man. The success of Detroit’s Charlie “Boss” Schmidt (5’11”, 200 pounds) was probably one of the reasons the Tigers gave another big catcher, John Peters, a look. His Baseball-Reference page lists him at an even six feet and 192 pounds, but many contemporary reports said that Peters was either 6-foot-2 or 6-foot-3 and weighed over 200 pounds. He picked up the nicknames “Big Pete,” “Big John,” “Long John,” and even “Moose.” However, despite his physical attributes and a respectable .265 career batting average in the big leagues, a strong but erratic throwing arm (which led to another nickname, “Shotgun”) limited Peters to just parts of four major league seasons.

John William Peters was born July 14, 1893, in Kansas City, Kansas. Peters could not be found in the 1900 US Census, so his childhood history and genealogy is mostly unknown. On his death certificate, the name of his father is listed as unknown but his mother is identified as Hanna (or Hannah) Brown of Gallatin, Missouri. She was born around 1873 and in the 1885 Kansas State Census, when she was around 12 years old, Hanna was living in Kansas City along with another household member named George Fortune. No birth records could be found for John, but in the March 1, 1905, Kansas State Census John Peters, age 14, was listed along with George Peters, age 12, possibly a younger brother, in the household of George and Mary Fortune in Kansas City. The relationship between the families is not known but this George Fortune was in all likelihood the same man who was living with Hanna Brown, John Peters’s future mother, twenty years earlier.

By the time of the 1910 US Census, when John would have been in his late teens, he was on his own, living as a boarder in Kansas City and working as a hostler in the stock yards. He started out catching for a semipro club in the Kansas City Intercity League in 1910 managed by Hall of Fame pitcher Kid Nichols. He also spent some time with an independent club in Colorado and early in 1912 it was reported that he had been signed by Topeka of the Western League and offered a tryout.[1] No record could be found of him playing for Topeka, and likely he returned to Colorado. Early the following year, 1913, he signed with the Davenport, Iowa, Blue Sox of the Class B III League. According to one report, the chief of police of Davenport was spending some time at a farm he owned in Colorado, had seen Peters play there, and recommended him to club officials.[2] He batted just .174 in 67 games in his first season in professional baseball.

The following season Peters joined the Grand Forks, North Dakota, Flickertails of the Class C Northern League. He enjoyed success at a lower classification, batting .307 in 101 games, and began to attract attention from major league scouts. In June, Chicago White Sox owner Charles Comiskey sent a letter to Grand Forks inquiring about a selling price for Peters[3] and followed that up by sending former White Sox catcher Billy Sullivan to look Peters over.[4] Peters also drew interest from the Cleveland Americans and Buffalo of the Federal League, but Flickertails player-manager Ed Wheeler, knowing he had a valuable commodity, kept holding out for a higher offer.

Wheeler finally sold him to St. Paul of the American Association in September, but soon thereafter Peters was acquired by the Detroit Tigers in what was called a “secret”[5] or “gumshoe”[6] draft. It was expected that he would compete with Red McKee and Del Baker for the backup role to starting catcher Oscar Stanage. Not yet 22 years old, Peters was at first reluctant about reporting to Detroit, feeling he did not have the necessary experience and would embarrass himself against big league competition. But once he reported to spring training in Gulfport, Mississippi, he quickly became the star of the camp. Manager Hughie Jennings said, “Pete’s work has impressed me very favorably and I believe that he is the man we have been looking for. … He looks as good now as any young catcher who has broken into the American League recently…”[7]

He made the club’s opening day roster and made his major league debut on May 1, 1915, against the White Sox in Chicago, going hitless in three at bats in a 5-0 Tiger loss. Other than rapping a single in an exhibition game against the Cincinnati Reds, Peters rode the bench the next couple of weeks before being optioned to the Chattanooga Lookouts of the Southern Association at the end of May. He backed up starting catcher Pop Kitchens and filled in in the outfield but batted just .187 in 67 games.

Initially Jennings and the Tigers remained high on Peters’s potential, claiming his demotion to the Southern Association was to get him regular work, rather than sitting on the bench in Detroit. He remained in Chattanooga the next two years (1916-1917) but his hitting went sour, batting just .222 and .215. One of the reasons for his drop-off may have been concerns over his wife’s health. Peters married Lucy Weakley in Kansas City on January 20, 1916. In September of that year, it was reported that his wife “was hovering between life and death from typhoid malaria for three months.”[8] Lucy recovered and the couple eventually had six children.

In March 1918 the Detroit Tigers, who still held his rights, sold him to the New Orleans Pelicans of the Southern Association. Being married and having a new baby, Peters was exempted from military service during World War I. Josh Billings, the backup catcher to Steve O’Neill in Cleveland, enlisted in the naval reserves, and Peters was purchased by the Indians before ever playing for New Orleans. With O’Neill out with an illness, he was given a start against the Athletics in Philadelphia on May 15. His return to the American League couldn’t have gone worse.

Three Athletic base runners attempted to steal second base in the first inning and each time Peters threw wildly and “…because neither [shortstop Ray] Chapman or Wamby [second baseman Bill Wambsganss] had a net,”[9] Peters, citing “shaky nerves,”[10] was charged with three errors. In the fourth inning Philadelphia’s Red Shannon attempted to steal second and Peters “thought he was playing catch with [centerfielder Tris] Speaker,”[11] as he overthrew the bag again for his fourth error of the game. To make matters worse, Shannon circled the bases and spiked Peters while sliding into home. This is where Peters picked up the nickname. “Shotgun.” Mercifully, he was pulled from the game in the fourth inning after going hitless in his only at bat.

The Indians kept him around for another couple weeks, mainly to throw batting practice, but he never appeared in another game. He was finally released on June 4 and returned to Kansas City where he played in a few games with the Blues of the American Association and area semipro teams. In spring 1919, he signed with the Birmingham Barons of the Southern Association, where regular work put his career back on track. Peters was given a third shot at the major leagues when in September of 1920 the Barons sent him to the Philadelphia Phillies in a deal to complete an earlier trade for Stuffy Stewart.[12] Apparently having solved his throwing accuracy problems, Peters showed well in spring camp and opened the 1921 season as the Phillies starting catcher. Later Frank Bruggy took over as the team’s regular catcher, but Peters had a solid season, batting .290 in 55 games. His highlight was a home run in the bottom of the ninth off Dolf Luque to give the Phillies a 5-4 win over the Cincinnati Reds on July 16.[13]

During an exhibition game in spring training the following March, Peters was hit above his heart by a pitched ball. He was revived after a few minutes and took his base. But after running from first to third when the next batter singled, he experienced intense pain in his chest and had to leave the game.[14] From all appearances, there were no lasting effects, and he spent the entire 1922 season with Philadelphia, backing up starting catcher Butch Henline. He repeated his late-inning heroics of the prior year on June 19 at home against the Cubs. Chicago scored two runs in the top of the ninth to take a 6-4 lead. The Phillies scored one in the bottom of the inning and with two on and two out Peters was sent up to pinch hit for pitcher Jesse Winters. Peters hit a three-run homer into the left field bleachers at the Baker Bowl to give the Phillies an 8-6 walk-off win.[15] For the season Peters again appeared in 55 games and batted .245.

In December the Phillies traded him along with Roy Leslie, John Singleton, and Jimmy Smith to Salt Lake City in the Pacific Coast League (PCL) for Heinie Sand. This ended a four-year major league career that consisted of two brief cups of coffee with the Tigers and Indians in the American League and two more seasons as a backup catcher for the Philadelphia Phillies in the National League. In 112 big league games Peters rapped 80 hits, including 13 doubles, a triple, and 7 homers, for a .265 career batting average. He drove in 47 runs and scored 22 times. His throwing issues resulted in 21 errors in 316 chances behind the plate for a .934 fielding percentage.

He got regular work behind the plate, logging 151, 141, and 139 games during the 1923-1925 seasons, and the high-altitude, hitter-friendly environment in Salt Lake City helped him post batting averages over .300 each season. In 1926 he followed his manager Ossie Vitt to the Hollywood Stars of the PCL and had another strong season, hitting .290 in 143 games. Peters had lost none of his competitiveness as evidenced by an incident late in the season. In the second game of a doubleheader against the San Francisco Seals on August 21, Peters began arguing ball and strike calls with home plate umpire George Goes. Vitt came onto the field, stepped on Goes’s toes, and after Goes swung his mask at Vitt, the two began throwing punches. At that point Peters joined in the fray and he and Goes wrestled until pulled apart by policemen.[16] Both Vitt and Peters drew indefinite suspensions.[17]

In December Peters had a chance to wind up his professional career near his home when Hollywood traded him to the Kansas City Blues of the American Association for Cotton Tierney.[18] He played five seasons for Kansas City (1927-1931) and was a member of the 1929 club that won the Junior World Series by defeating the Rochester Red Wings of the International League, five games to four. Other than missing part of the 1930 season with a knee injury, he caught nearly every game and maintained a .300 batting average in all but one season, when he slipped to .289. In 16 full minor league seasons, Peters hit .300 or better in eight of them.

Throughout his career Peters made Kansas City his off-season home and each winter worked for the Armour Company, at first buying and selling livestock in the stockyards, then working in the packing plant, and later as a member of the “steam fitting gang.” After the 1928 season it was remarked that Peters catching nearly every Blues game “left him so weak he could hardly lift a cow … but ten hours a day at the packing plant has seemed like a vacation to him and he is back to the point where he can lift a good-sized bull in either hand.”[19]

While playing for the Blues, Peters found time to get involved with an organization that helped provide financial assistance to disabled ball players,[20] and provide instruction to prospective young catchers at a youth baseball school in Kansas City.[21] He taught the youngsters about the importance of learning a batter’s weaknesses and how to disguise signals from the opposition. And, for someone who once picked up the nickname “Shotgun,” Peters taught the kids the proper footwork and technique in making strong throws to the bases. “In appreciation for his faithful work,”[22] Blues president George Muehlebach arranged for a “John Peters Day” between games of a doubleheader against St. Paul on July 10, 1929. A collection was taken and Peters was presented with a new green Whippet automobile,[23] a sedan large enough for his growing family.

During the winter of 1931-32 Peters, his wife Lucy, and their five children were temporarily living with his mother-in-law, Alice Weakley, with plans to purchase a new home in the Kansas City suburbs in the spring. On the evening of February 21, 1932, he was sitting in Mrs. Weakley’s living room when he suddenly slumped over and died. A fatal heart attack was later confirmed in an autopsy and his death certificate lists “acute dilated right heart” as the cause of death. He was just 39 years old.[24] It is not known whether the injury sustained earlier in his career, when he was hit by a pitched ball near his heart in a spring training game, was a contributing factor in his death.

After services at Latter Day Saints Church, Peters was buried at Memorial Park Cemetery in Kansas City, He was survived by his wife Lucy and their five children, Alice Hannah, age 15, John William, Jr. 12, Elizabeth, 11, Leonard Scott, 8, and Charles Kenneth, 5. His death notice said, “Another child survives by another marriage”[25] but no information could be found about an earlier marriage or another child. Lucy later remarried and lived to be 97 years old. After her death in 1994 she was also buried at Memorial Park.

John would have been proud of his family. His daughters both married and John Jr. served in the army during World War II and later became a pastor in Ft. Wayne. Indiana. Leonard served in the Army Air Force during the war and later worked as a firefighter and police officer in the Kansas City area. The youngest, Charles, had a long career with the Kansas City Parks Department before his death in 1998.

Dutch Zwilling, his manager with the Blues, said, “[Peters was] one of the most loyal players who ever wore a Kansas City uniform. Never a word from John Peters when he was asked to catch a doubleheader or warm up some pitcher. Although old in point of service, he will be hard to replace on the Kansas City club.”[26] Ed Pollack of the Philadelphia Public Ledger wrote, “Big John Peters was another who was liked by all his companions. All those who knew him read of his death with great sorrow. Measured according to big league standards, Pete wasn’t much of a catcher, but he was a grand chap.”[27]

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Bill Lamb and Norman Macht and checked for accuracy by SABR’s fact-checking team.

Sources

Unless otherwise noted, Peters’s playing statistics were taken from Baseball-Reference.com and family and genealogical information from Ancestry.com.

Notes

[1] “Topeka Signs John Peters,” Kansas City Times, February 9, 1912: 10.

[2] “Another Backstop,” Quad City Times (Davenport, Iowa), March 6, 1913: 7.

[3] “White Sox Want Peters and Ask Concerning Dutch,” Grand Forks (North Dakota) Herald, June 23, 1914: 1.

[4] Scout Sullivan Saw Teams Play”, Grand Forks Herald, June 29, 1914: 11.

[5] “Peters to Tigers,” Grand Forks Herald, September 24, 1914: 9.

[6] Detroit Free Press, September 25, 1914: 12.

[7] “Peters Has Job as Catcher Won,” Detroit Free Press, March 10, 1915: 10.

[8] Kansas City Star, September 23, 1916: 4.

[9] “Fourteen Errors Are Made in Poor Baseball Exhibition,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, May 17, 1918: 13.

[10] “Peters Somewhat Nervous in First Games in Majors,” New Orleans Item, May 17, 1918: 13.

[11] Same as above.

[12] Birmingham (Alabama) News, September 20, 1920: 11.

[13] Hats Off to Peters,” Philadelphia Public Ledger, July 18, 1921: 15.

[14] “Wild Pitch Knocks Out Jack Peters,” Philadelphia Inquirer, March 16, 1922: 16.

[15] “Jack Peters Wins with Timely Homer,” Philadelphia Inquirer, June 20, 1922: 14.

[16] “Goes Defeats John Peters by One Tumble,” San Francisco Chronicle, August 22, 1926: 1H.

[17] “Vitt, Peters Are Suspended,” San Francisco Chronicle, August 24, 1926: 25.

[18] “’Cot’ Tierney is Traded,” Kansas City Times, December 9, 1926: 16.

[19] “John Peters is Getting Back His Strength,” Kansas City Star, December 21, 1928: 28.

[20] “Magnates Offer Assistance,” Kansas City Star, December 22, 1926: 28.

[21] “Hey You Young Catchers, See How It’s Done at the Star’s Baseball School,” Kansas City Times, May 10, 1930: 19.

[22] “Plan A John Peters Day,” Kansas City Star, June 30, 1929: 20.

[23] “John Peters Finds This Present from the Fans Worth Waiting For,” Kansas City Times, July 12, 1929: 12.

[24] “John Peters Dies,” Kansas City Times, February 22, 1932: 10.

[25] Same as above.

[26] Same as above.

[27] “Praises Ex-Pel, John Peters,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, March 2, 1932: 13.

Full Name

John William Peters

Born

July 14, 1893 at Kansas City, KS (USA)

Died

February 21, 1932 at Kansas City, MO (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.