John Schorling

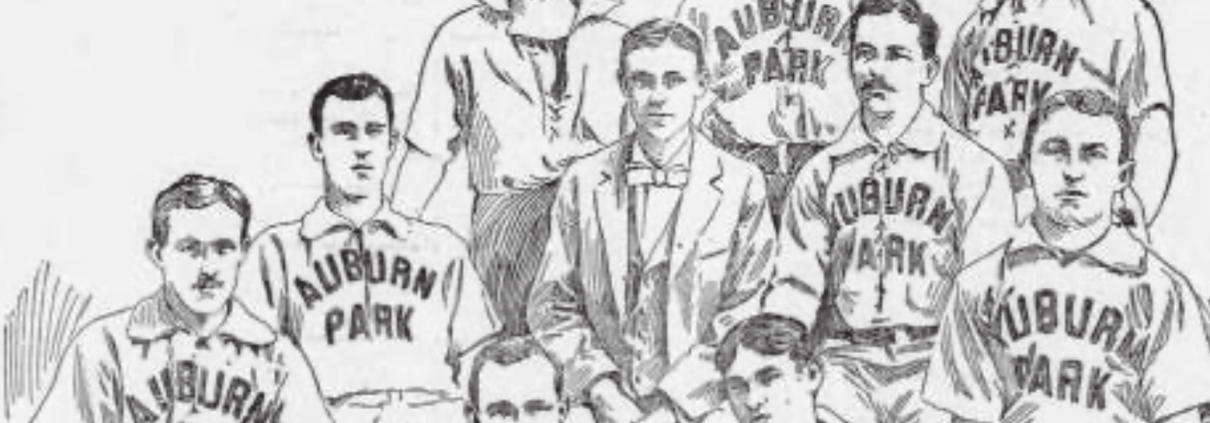

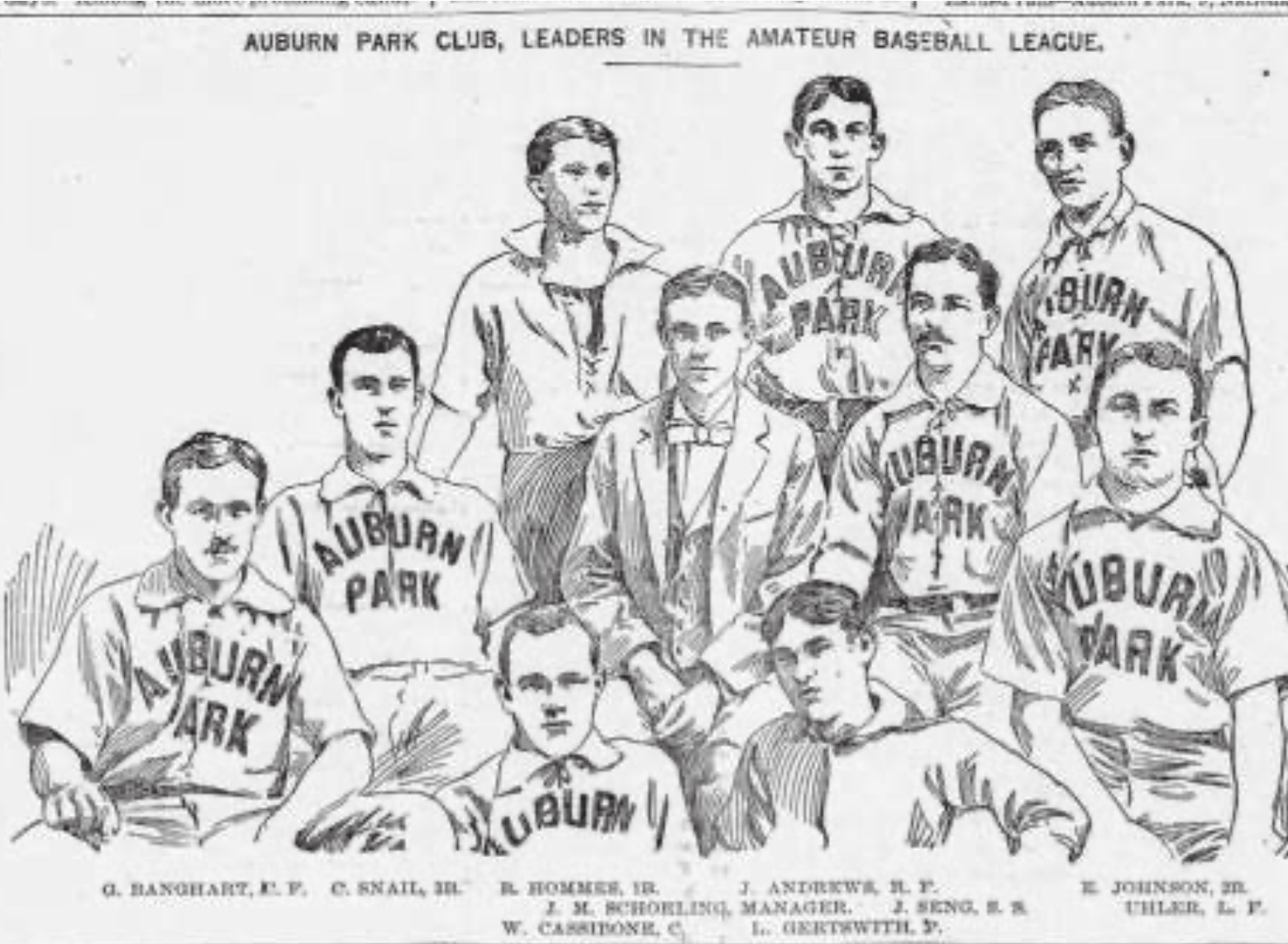

John Schorling (center in suit and bow tie) was Rube Foster’s business partner and the American Giants’ home field, Schorling Park, bore his name for several years (Photo: Chicago Defender, September 21, 1986)

An examination of John Schorling’s life yields more questions than answers. This is true of many individuals who lived in pre-internet times, especially those who were not famous or who had no offspring to further their story. It seems especially true for Schorling. How did he get involved with baseball? Was he ever a player or did he want to be a manager and booking agent? How did he come to be a business partner with Rube Foster? What was his relationship with Charles Comiskey? What did he do after he divested himself from the Chicago American Giants? Some of these questions can be answered, at least partially, but many mysteries remain.

Schorling was born on December 16, 1865, in Michigan City, Indiana,1 to August (recorded as Angus in both the 1860 and 1880 censuses) and Sophia Schorling. The elder Schorling was a sash and blind maker in Michigan City, but the family relocated to Chicago after the Great Fire of 1871 and settled on the South Side near the intersection of 79th Street and Vincennes Avenue. They lived with Sophia’s father, Charles Duensing, at the Ten Mile House, a tavern for travelers going to or from Chicago, and he soon took over as proprietor.2 The elder Schorling purchased a large tract of land, presumably to develop into homes as Chicago recovered from the effects of the Fire, calling the subdivision Auburn.3 It was here where a ballpark was built that became home to the Auburn Park team that the younger Schorling would manage. No records have been found to determine when the ballpark was built, or if it was August or John who had the idea.

John Schorling was interested in baseball as many young men were in this age but managing a semipro team likely did not pay the bills, so other work was needed. In 1892 Schorling was identified as a coal dealer by the Chicago Inter Ocean in an article about the missing postmaster of the Auburn Park post office. Schorling and two others had posted the bond of postmaster John Hallenbeck, who left a note for his family in one of his shoes and disappeared. Schorling and the other bondsmen went to the post office and began sorting mail to get the office operational. Schorling had also helped to establish the Auburn Park Bank with Hallenbeck, who had a mortgage there as well.4 It was thought that because of overwork the postmaster may have committed suicide.5

Schorling continued his work as a coal dealer at the turn of the century, but this was to change. August Schorling had built a tavern at 79th & Vincennes called Schorling’s Corner and, upon his death in 1904, John Schorling added the business to his duties with the Auburn Park team and ballpark.6 The ballpark housed a number of other squads besides the Auburn Park team, notably as the occasional home of the Chicago Union Giants (1900-1904) and Leland Giants (1905-1909), prominent Negro teams that played in the Chicago semipro leagues as well as nationally against other Negro teams. Frank Leland, who managed the Union Giants and the renamed Leland Giants, recruited Foster in 1902 to pitch for his team.7

After several years with the Philadelphia Giants, during which he led them to three consecutive championships.8 Foster rejoined the Leland Giants in 1907 as a pitcher and manager.9 Foster’s relationship with Leland deteriorated over the next several years and, with Schorling continuing to book teams into the Auburn Park facility, a relationship was established. With Foster now controlling all aspects of the Giants’ operations, he decided to break ties with Leland and partnered with Schorling to form one of the most important teams in Negro baseball history, the Chicago American Giants.

After the Chicago White Sox moved to the new “Baseball Palace of the World” at 35th and Shields, their original ballpark at 39th and Wentworth was vacant. Schorling leased the grounds and rebuilt the grandstand that Charles Comiskey had dismantled after he moved his franchise four blocks north.10 “Schorling got hold of the South Side park, constructed a ‘palatial plan,’ and chose ‘yours truly,’ Foster noted, ‘as the best available personage to organize and head a club.’”11

The relationship between Foster and Schorling, which began with only a handshake agreement, endured until Foster’s untimely health issues began in 1926. In a January 1924 Chicago Defender article, Foster wrote:

Mr. Schorling is one of the best and most honorable men I have ever come in contact with. He made it possible for us to enjoy baseball in the city. The park was built exclusively for us, has been used the same way, and is an investment that runs into thousands of dollars. He has allowed to be paid through my hands over $700,000 to Colored people alone. In our 12 years together, there has never been a difference of opinion. He has never asked me why I did anything or censured me for any steps taken. He has paid me more than any man before; he has given me many thousands of dollars that I knew did not come from the games, as it was just three years ago we were able to pay for the park.

You can see or better judge the type of man he is when you take into consideration that every game, all contracts and permission for the use of the park, what anyone receives, all help and employees, rental of grounds have been trusted to me, and no one has been able to do any business with him until they came to me. This will give you better insight into how some men are made. When he wanted me he said, “I am fixing to invest lots of money in baseball. I want you with me. Name the terms.” I told him. He said: “If that’s what you want you must be worth it.” That was our last business talk. This was 12 years ago.12

Others could see the strength of the relationship between the two as well. Dave Malarcher, an American Giants player who took over as the team’s manager when Foster was stricken, said, “Both must have felt that they would live forever, and that they would need each other as long as they lived.”13 Others in the Negro baseball community were not as impressed with the relationship between the White tavern/ballpark owner and the Black manager. In a response to a dispute regarding gate receipts, Hilldale owner Edward Bolden asked the Baltimore Afro-American in 1923, “Why does Mr. Foster publish the fact that Schorling Park and the American Giants are the property of John Schorling, for whom the park is named, and Foster is but a chattel of his white boss?”14

The lack of a written contract came back to haunt the Foster family when, upon Foster’s confinement to an insane asylum, Schorling took over total control of the American Giants.15 While Schorling attended the Negro National League meetings in January of 1927 with Foster’s wife, Sarah, he also attended a Whites-only dinner of NNL owners who had hoped to take more control of the league.16 Sarah Foster tried to assert that Rube Foster was the team owner and that, as Rube’s guardian, she should control the team. Schorling ignored Sarah’s claim and acted as both owner and landlord of the American Giants until he sold the team to William Trimble in 1928.17

Game action at South Side Park, later Schorling Park, in 1907. (CHICAGO HISTORY MUSEUM)

Once his financial interest in baseball had ended, Schorling turned to other ventures. The 1930 Census records his occupation as “real estate investment.” After Schorling had taken over South Side Park when the White Sox vacated it in 1910 and rebuilt it as Schorling Park, he shut down his Auburn Park facility on 79th Street and began to subdivide the property his father had originally purchased. At this point in his life, John Schorling’s trail grows cold. The only news about him to be found after 1930 is his obituary. Schorling died from pneumonia on March 23, 1940, and was buried at Mt. Greenwood Cemetery in Chicago. He and his wife had no children, and Maud Payro Schorling died in 1950.

Schorling had married Maud Payro in 1898.18 According to the 1900 Census, Payro’s father was Canadian, and her mother was from Michigan. The 1900 Census also indicates that Charles Comiskey and his wife, Annie, had one child, 14-year-old Louis, who was their only living offspring. Several modern sources19 state that Schorling was the son-in-law of Charles Comiskey, attempting to make a connection to Schorling’s acquiring Comiskey’s original ballpark. During the period of 1910-1911, no mention was found stating that it was Comiskey’s son-in-law who took over his ballclub’s former home. The fact that Comiskey removed sections of the grandstand makes it difficult to believe that there was anything but a business relationship involved here, especially considering that Comiskey’s only offspring was his son when the Schorlings married. If there was any relationship between the two, it died when Schorling passed away.

Notes

1 https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/53370878/john-m-schorling.

2 John Drury, “Old Chicago Houses,” Chicago Daily News, April 19, 1940: 18.

3 John Drury, “Pioneer Inn Marked the Beginning of Auburn,” Chicago Daily News, May 1, 1958: 2.

4 “Message in a Shoe,” Chicago Inter Ocean, December 15, 1892: 1.

5 “Did Hollenbeck Kill Himself”, Chicago Tribune, December 16, 1892: 5.

6 “Old Chicago Houses.”

7 Robert Charles Cottrell, The Best Pitcher in Baseball (New York: New York University Press, 2004), 10.

8 Cottrell, 20-29. The term championship, especially in the days prior to the formation of the Negro National League in 1920, is always suspect. For example, the Philadelphia Giants won the “colored world’s championship” in a series against the Atlantic City Royal Giants in 1905. In 1906, the Philadelphia Giants won the loosely formed “League of Independent Professional Ball Players.”

9 Cottrell, 32.

10 “Fire Destroys American Giants Ball Park Seats,” Chicago Defender, January 4, 1941: 24.

11 Cottrell, 66.

12 Andrew Rube Foster, “Rube Foster Has a Word to Say to the Baseball Fans,” Chicago Defender, January 5, 1924: 8.

13 Cottrell, 121.

14 “Bolden Replies to Charges of Rube Foster,” Baltimore Afro-American, January 26, 1923: 12.

15 Cottrell, 171.

16 Paul Debono, The Chicago American Giants (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2007), 115.

17 Debono, 116.

18 https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/53370878/john-m-schorling.

19 An incomplete listing of sources naming John Schorling as Charles Comiskey’s son-in law includes these: Cottrell, 62; James A. Riley, The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues (New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers, Inc., 1994) as published at the Negro League Baseball Museum’s eMuseum page https://nlbemuseum.com/history/players/fostera.html; Debono, 32; Rube Foster’s page at the SABR BioProject: https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/andrew-rube-foster/; Rube Foster’s page at the Baseball Hall of Fame: https://baseballhall.org/hall-of-famers/foster-rube.

Full Name

John Schorling

Born

December 16, 1865 at Michigan CIty, IN (US)

Died

March 23, 1940 at Chicago, IL (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.