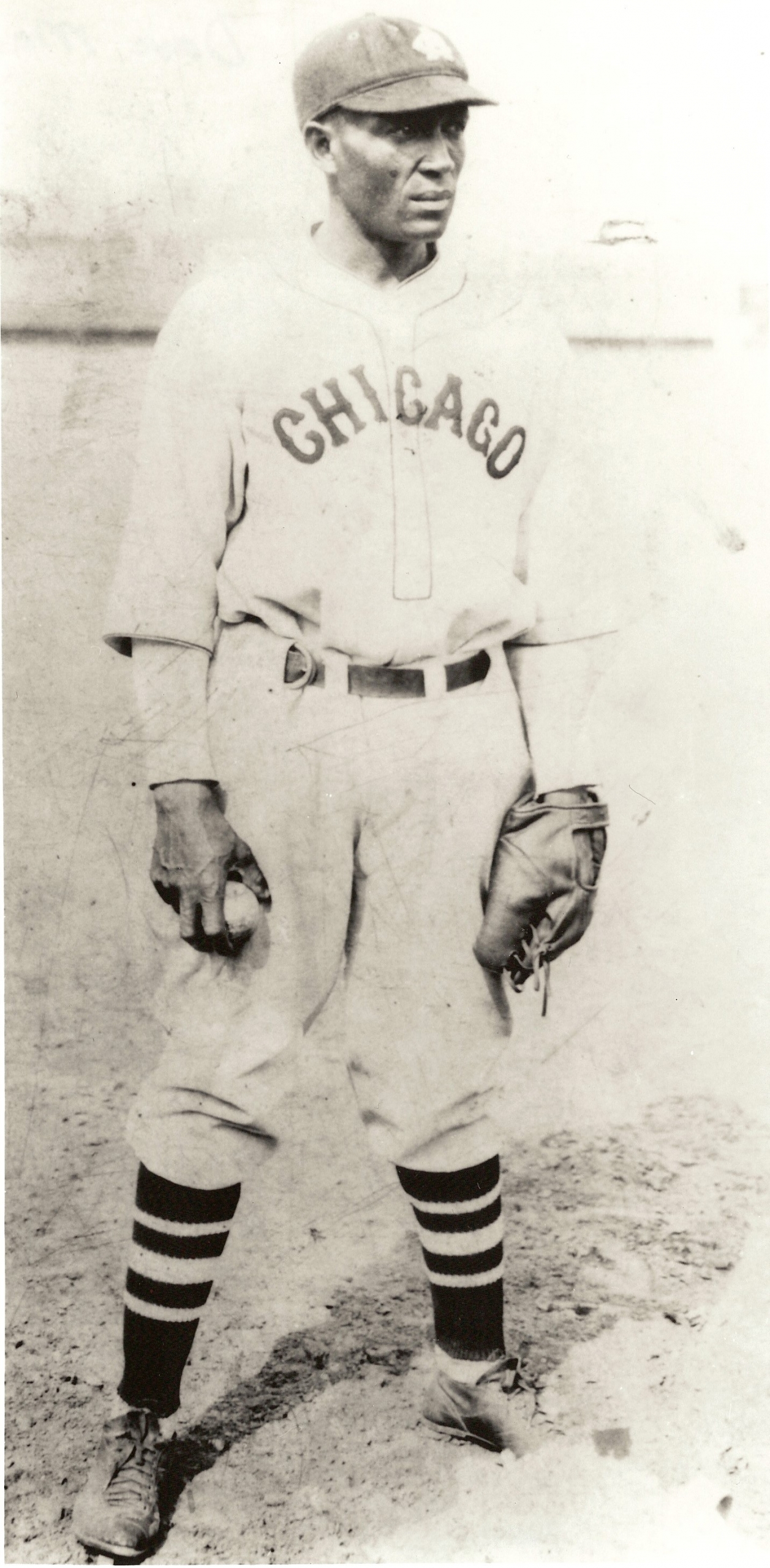

Dave Malarcher

Dave Malarcher was an erudite, disciplined, and reverent man known appropriately as Gentleman Dave. As a player, he was a small (5-feet-7 and 150 pounds during his playing days), speedy, and smart third baseman, whose play embodied the methodology of one of his mentors, Rube Foster. Malarcher later became a manager, utilizing what he learned from Foster and his other great mentor, C.I. Taylor, to great success. Malarcher led his teams to multiple championships and always had the respect of his players. As was written in an article when he left baseball, “he was a perfect model for young ballplayers – he was a credit to baseball in Chicago and the nation over.”1

Dave Malarcher was an erudite, disciplined, and reverent man known appropriately as Gentleman Dave. As a player, he was a small (5-feet-7 and 150 pounds during his playing days), speedy, and smart third baseman, whose play embodied the methodology of one of his mentors, Rube Foster. Malarcher later became a manager, utilizing what he learned from Foster and his other great mentor, C.I. Taylor, to great success. Malarcher led his teams to multiple championships and always had the respect of his players. As was written in an article when he left baseball, “he was a perfect model for young ballplayers – he was a credit to baseball in Chicago and the nation over.”1

David Julius Malarcher was born on October 18, 1894, in Whitehall, Louisiana. He was the youngest of 11 children, with seven sisters and three brothers. His mother, Martha (Campbell) Malarcher, had been born into slavery and later worked as a midwife and caretaker for the children in the homes of plantation owners. His father, Henry Louis Malarcher, was a field laborer on the local sugarcane plantations. Martha Malarcher valued education and made sure that all her children received some teaching. One of Dave’s older sisters ran the first school that he attended. Malarcher reported having a pleasant childhood that included swimming in the Mississippi River and playing baseball.2

In 1907 Malarcher moved to New Orleans, where he worked as a laborer for a wealthy family. While there he attended New Orleans University, which offered African American children opportunities that ranged from elementary education to college-level studies. Malarcher continued to attend New Orleans University through his college years and played for the school’s baseball team, serving as team captain.3 From 1913 to 1916, Malarcher also played for the New Orleans Black Eagles, a strong semipro team that played throughout Louisiana and East Texas. It was at this time that Malarcher developed his ability to switch-hit. While playing in a game for the Black Eagles against the Indianapolis ABCs, who were barnstorming their way north from a trip to Cuba in the winter of 1915-1916, Malarcher caught the attention of C.I. Taylor, the ABCs’ owner and manager.4 Taylor offered Malarcher $50 a month to play for the ABCs, and he jumped at the chance, although he joined the ABCs to play in the summer and continued to attend college in the winter.5

Malarcher joined a strong Indianapolis team. The 1916 ABCs featured such great players as Bingo DeMoss, Dizzy Dismukes, 19-year old Oscar Charleston, and three of C.I. Taylor’s siblings: Ben Taylor, Candy Jim Taylor, and Steel Arm Johnny Taylor. In addition to learning from his fellow players, Malarcher was under the tutelage of one of the greatest baseball mangers of his or any time, C.I. (for Charles Isham) Taylor. Taylor had an enormous impact on Malarcher, teaching him a great deal, especially about how to run a baseball team. Taylor stressed physical conditioning, nurturing his players as they developed, and he concerned himself with what his players did off the field, including strongly discouraging them from drinking both in and out of baseball season.6 As a 21-year-old rookie, Malarcher played 16 games at second base and two games at shortstop and compiled a slash line of .275/.339/.373. After the season, Malarcher returned to college in New Orleans. In 1917 he rejoined the ABCs as the starting right fielder. In addition to the 39 games he played in right field, Malarcher also played 13 games at third base, three games at second, one at shortstop, one as a pitcher, and three games as a catcher when both catchers on the team were out with injuries. For the season, Malarcher posted a slash line of .233/.308/.285. He began to show what would become his trademark patience at the plate and he led the team in sacrifice hits.

The 1918 season started with the threat that the United States’ entry into the Great War would impact professional baseball and its players. Malarcher and several of his teammates had registered for the draft and were notified that they could be conscripted at any time. Malarcher returned to the ABCs and assumed a new starting position, third base, which became his primary position for the remainder of his playing career. He had a strong arm and gained renown as one of the best defensive third baseman in Negro League history.7 Batting second in the order, Malarcher played in 39 games before he was drafted in late July. He compiled a slash line of .250/.364/.297 and, despite leaving in midseason, led the team in walks and sacrifice hits. Malarcher’s approach at the plate embraced the small-ball strategies employed by C.I. Taylor.

After being drafted, Malarcher reported to Camp Dodge in Johnston, Iowa, on August 22, where he was assigned to the 809th Pioneer Infantry Regiment, an African American unit. A number of his ABCs teammates and other Negro League players also served in the 809th. Malarcher shipped out to France, arriving in September, but never saw action as the war ended soon after he arrived (on Armistice Day, November 11, 1918). While in France, Malarcher played baseball for his unit’s baseball team in the American Expeditionary Force League. His baseball prowess was also on the mind of a stateside rival baseball manager. While stationed in St. Luce, France, Malarcher received a letter from Rube Foster, the Chicago American Giants’ owner and manager, inviting him to play for the American Giants after his military service.8

Malarcher was discharged from the Army on August 2, 1919.9 Upon his return to the United States, he was given $60 by the Army and returned to Indianapolis. He wanted to go to Louisiana to see his mother and girlfriend but did not have enough money to make the trip. Malarcher requested a $75 loan from C.I. Taylor, who declined to lend the money right away; thus, Malarcher decided to head to Chicago to see Rube Foster. Foster lent him the money without hesitation, establishing a business and personal relationship between the men for years to come.10 In addition, Foster facilitated the signing of Malarcher to play the remainder of the 1919 season with the Detroit Stars.11 Foster had backed the Stars’ ownership; therefore, he had an interest in the team’s success. Oscar Charleston joined Malarcher in playing out the season with the Stars. Malarcher played only eight games for Detroit, all at third base, but showed little rust from his time away, collecting 11 hits and scoring eight runs in the limited action.

In 1920 Malarcher played for Foster’s Chicago American Giants in the newly formed Negro National League. Then 25 years old, Malarcher was the best third baseman in the Negro Leagues. The 1920 Chicago American Giants were a great team, led on offense by Cristobal Torriente, who posted a league-leading 1.085 OPS, and Bingo DeMoss, who had a .799 OPS. Malarcher had a .669 OPS for the season. The team’s pitching staff, which featured Dave Brown, Tom Williams, and Tom Johnson, was the strength of the team. For the season, the American Giants’ team ERA was 2.32, which was 1.20 runs per game better than the league average. The team finished with a record of 43-17-2 in the Negro National League, far and away the best record in the league. In addition to having on-field success, Malarcher also experienced joy away from the baseball diamond when he married Mabel Sylvester on June 16, 1920.12

Malarcher quickly became a disciple of Foster’s brand of scientific baseball, and his skill set matched up well with Foster’s approach to manufacturing runs. Malarcher was a patient hitter and a fast and smart baserunner, and was proficient at advancing runners – an ideal Deadball Era player. Additionally, Malarcher was eager to learn from Foster, both in terms of baseball strategy and in terms of leadership and business management. These skills benefited Malarcher later in life both as a manager and in his post-playing career.13

The 1921 Chicago American Giants relied on pitching, defense, and manufacturing runs to finish atop the Negro National League standings once again with a record of 44-22-2 in league play. Malarcher batted only .209 for the season, but he continued to draw walks and steal bases, and he also contributed solid defense at third base.

In 1922 the American Giants captured the Negro National League pennant for the third consecutive season. Malarcher, however, had a tough season, suffering multiple injuries that sidelined him for the majority of the campaign. In May he tore ligaments in his chest, reportedly near his heart, which kept him on the bench.14 When he came back, he was spiked while attempting to steal second and had to be carried off the field. Power-hitting John Beckwith, one of the most feared hitters in the game, took Malarcher’s place in the lineup while he was out. Malarcher eventually returned and had a dramatic hit in one of the most intense games of the 1922 season. On August 16, the American Giants faced off against the Bacharach Giants at Schorling Park in Chicago. Beckwith started the game at third base but was replaced by Malarcher when the scoreless game went into the ninth inning. The game continued to be a scoreless affair until the bottom of the 20th inning, when Cristobal Torriente drew a leadoff walk, advanced to second on a sacrifice bunt, and scored on Malarcher’s base hit to give the American Giants a 1-0 win.15

Malarcher was healthy again for the 1923 season and, at age 28, was entering the prime of his career. He manned the hot corner once again, with John Beckwith moving over to first. For the season, Malarcher hit .304/.386/.411, batting over .300 and slugging over .400 for the first time in his career. Despite Malarcher’s strong season and stellar performances from teammates Beckwith and Torriente, the American Giants regressed as a team and did not finish in first place for the first time since the inception of the Negro National League.

After the season, the American Giants faced the American League’s Detroit Tigers in a three-game set. Although Ty Cobb did not play in the series, the Tigers still featured Harry Heilmann, Heinie Manush, and Bobby Veach in their lineup. The American Giants fortified their lineup by adding Oscar Charleston. The teams played to a 5-5 tie in the first game, the Tigers prevailed by a score of 7-1 in game two, and the American Giants won game three, 8-6.16 Malarcher had an excellent series, batting .364 and playing flawlessly at third base. After the 1923 season Commissioner Kenesaw M. Landis decreed that only all-star White teams could play Negro League teams in the future as Negro League teams were regularly defeating White major-league teams.

Malarcher again manned third base for Chicago in 1924 and had another solid season, batting .280 and leading the team in runs scored with 69 (over 77 games) while also stealing 22 bases. Nevertheless, the American Giants finished a distant second to the Kansas City Monarchs, who defeated the Eastern Colored League’s Hilldale Club in the first Negro League World Series.

In 1925 Malarcher was paid $225 a month, with a $500 bonus at the end of the season.17 He split his time between third base and second base, covering the keystone sack while regular second baseman Bingo DeMoss left the team for a time in midseason. On offense, Malarcher had perhaps his best season and was arguably the best hitter in the American Giants lineup, sporting a slash line of .324/.410/.381 and again leading the team in runs scored and stolen bases. The American Giants, however, did not have great season, finishing in third place behind the Monarchs and St. Louis Stars.

The 1926 season proved to be a monumental one in the life of Dave Malarcher as well as in the history of the Negro Leagues. After their third-place finish in 1925, Rube Foster chose to dismantle much of the American Giants roster. He traded Cristobal Torriente, the team’s best player over the previous six seasons, to the Kansas City Monarchs, and dealt Bingo DeMoss and two other players to the Indianapolis ABCs. The trades made for a younger roster for the American Giants, and perhaps also brought about greater parity in the league. Malarcher took over as Chicago’s team captain, a role that had previously belonged to the departed DeMoss.18 His pay was increased to $250 a month, reflecting his increased responsibility and importance to Foster’s squad.19 The team played well over the first half of the season; however, during that period, Rube Foster occasionally displayed erratic and unstable behavior. At the halfway mark in the season, Foster agreed to a vacation, and Malarcher took over as manager. Later that summer, Foster was arrested after several violent incidents. He was eventually deemed mentally irresponsible and was committed to an asylum in Kankakee, Illinois, where he remained until his death on December 9, 1930. Rube Foster, the most important figure in the history of the Negro Leagues to that point, never returned to baseball.20

Despite the turmoil of the first half of the season, the American Giants had played well. In the second half of the season, under Malarcher, they excelled. Pitcher Willie Foster, Rube’s half-brother, blossomed and became the rotation’s ace. The American Giants won the second half of the Negro National League season with a record of 30-7-2 and earned the right to face the Monarchs in a best-of nine championship series. Although the American Giants lost the first three games, they came back to win three of the next four. The teams agreed that if two more games were required, they would play a doubleheader. Willie Foster matched up against Kansas City’s ace pitcher and manager, Bullet Rogan, in game eight of the series, and the American Giants prevailed, 1-0, on a ninth-inning run. Incredibly, with the series on the line, Foster and Rogan both pitched the second game of the doubleheader as well. With darkness coming on, the teams agreed to limit the game to five innings. Foster again was dominant, and the American Giants won, 5-0, which propelled the team to the Negro League World series, in which they faced the Atlantic City Bacharach Giants.

The nine-game World Series was scheduled to be played in Atlantic City, Baltimore, Philadelphia, and Chicago. After the first game ended in a tie, Atlantic City won four of the next seven games (with another tie game in the mix), including a no-hitter thrown by Red Grier. The Bacharachs stood one victory away from winning the series, but the American Giants again staged a comeback and won the final three games of the series, with Willie Foster pitching a 1-0 shutout in the clinching game. Malarcher had led the team through the challenges of the season, and through two tough series comebacks, to a championship.21

The 1927 season marked a time of continued change for the American Giants. It was clear that Rube Foster would not return to the team, so Malarcher was named as the permanent manager. The team got out of the gate fast and won the first half of the season. Malarcher held down third base and provided a steady managerial hand. The Birmingham Black Barons won the second-half title to set up a championship series against the American Giants. Included on the Black Barons’ pitching staff was 20-year-old Satchel Paige, who started one game in the series but did not factor in the decision. The American Giants toppled the Black Barons four games to one to advance to the Negro League World Series, a best-of-nine set against the Atlantic City Bacharach Giants. Chicago took the first four games in the series but then lost three in a row to Atlantic City. However, the American Giants were able to clinch a second straight World Series title, with Willie Foster again winning the final game.22

The 1928 campaign was a tumultuous one for Malarcher and the American Giants and began with a dispute over the ownership of the team. After Rube Foster had been institutionalized, his wife, Sarah Foster, had tried to assert her rights to the ownership of the team. Foster’s White business partner, John Schorling, rebuffed Sarah Foster and took full control of the team for himself. Then, halfway through the 1927 season, Schorling sold the team to William Trimble, a White racetrack owner. As time passed, it became clear that Trimble was not a fully committed owner: He paid low salaries and devoted little attention to the team. As if these challenges were not enough for Malarcher, in mid-May he broke a bone in his shoulder, leaving him unable to play or to manage the team. He missed more than half the season and, in his absence, veteran pitcher George Harney took over the managerial duties. Several other players suffered injuries during the season, forcing the team to sign other players and use a multitude of lineups during the season. Despite all of this, the American Giants were able to win the second-half league title. This time around, Chicago faced the St. Louis Stars, who featured a lineup that included Cool Papa Bell, Mule Suttles, and Willie Wells, in a nine-game championship series. (There would be no World Series, because the Eastern Colored League had disbanded earlier in the season.) The Stars prevailed in the series, five games to four.23 After the season, Malarcher threatened to leave the Giants, asserting that he had not been compensated as manager of the team since Trimble assumed ownership.24 After a meeting with Trimble did not resolve the matter, Malarcher made good on his threat and left the team. He said he preferred to devote his time to his insurance and real estate businesses, which he had previously pursued only in the offseason.

Malarcher was out of the Black major leagues in 1929 and 1930. Although he did work full-time in insurance and real estate, he also led semipro teams – the American Eagles in 1929 and the All-Stars in 1930 – that featured some former players from the American Giants. The teams played locally in Chicago.25 The end of 1930 brought about another event of huge impact, the death of Rube Foster on December 9. At his funeral, Malarcher’s wife, Mabel, sang a solo as a part of the service.26

In 1930 William Trimble, recognizing the challenges of owning a team during the Depression, sold the team to Charles Bidwill.27 However, the remaining American Giants players jumped to other teams, and Bidwill was unable to field a team in 1931. Meanwhile, Malarcher took a leadership role in a newly formed team that became known as the Columbia American Giants, a squad that essentially took the place of the Chicago American Giants in the still-extant Negro National League. The league was a shadow of its former self, however, without a formal schedule or any plans for playoffs.28 After playing into early July and posting a record of 6-17-1, Malarcher decided to drop out of the NNL and turned the team into a semipro squad.

In 1932 the American Giants team was revived under the ownership of Robert Cole, a Black Chicago-based undertaker who had acquired the franchise. One of the first things Cole did was to hire Malarcher as manager. The team, now referred to as either Cole’s American Giants or the Chicago American Giants, played in the newly formed Negro Southern League. All indications were that the team would have a good season after it signed Willie Foster to anchor the pitching staff and Turkey Stearnes to lead the offense. Malarcher, 37 years old and having not played since 1928, was now a full-time manager, although he made appearances in two games during the season. The American Giants won the first half of the season and finished the season with a 34-12 record in NSL games. They faced the Nashville Elite Giants, the league’s second-half champions, in a best-of-seven championship series and won the pennant in seven games.29

In 1933 the second incarnation of the Negro National League, led by Pittsburgh Crawfords owner Gus Greenlee, began play, and Cole’s American Giants returned to the NNL fold. The American Giants ended up playing most of their home games at Perry Stadium in Indianapolis after they were no longer able to play in Chicago because Schorling Park, their home ballpark since 1910, was being converted to a dog-racing track.30 Willie Foster and Turkey Stearnes returned to the team, and Cole and Malarcher were also able to sign Mule Suttles and Willie Wells to give the team a potent offense. The American Giants averaged 7 runs per game for the season and finished with a 41-22-1 record. The American Giants believed that they had the best record in the first half of the season, and were entitled to a playoff. However, the Pittsburgh Crawfords were named the league champions by their owner and the league commissioner, Gus Greenlee.31

In 1934 the core of the American Giants – Stearnes, Wells, Suttles, Willie Foster, and manager Malarcher – all returned to the team, and the team itself returned to Chicago for its home games after the dog-racing track failed. Over the course of the season, Malarcher experienced the best and worst of Black major-league baseball.

A personal high point took place when Malarcher managed the West team in the second annual East-West All-Star Game, the biggest event in the Negro League season. The game was played on August 26 at Comiskey Park and drew a crowd of 30,000. The game was a pitching duel, with Willie Foster pitching the final three innings for the West and Satchel Paige pitching the final four innings for the East, and the East winning, 1-0.32

The American Giants finished with a 28-20-3 record and won the league’s second-half title. The Philadelphia Stars, winners of the first half, took on the American Giants in a wild best-of-seven championship series. However, the culmination of the series eventually drove Malarcher out of baseball. The American Giants won the first two games in the series, but the Stars came back until the series was tied at three games apiece. The seventh game in the series ended in a tie, thus extending the series by another game. In the eighth game, the Stars won, 2-0, to capture the pennant.33 However, Malarcher was upset about the events that unfolded during the final game and filed multiple protests. His primary complaint concerned the fact that Stars slugger Jud Wilson had punched umpire Bert Gholston during the game but had not been ejected. League Commissioner Rollo Wilson agreed that Jud Wilson should have been removed from the game, but he did not allow Malarcher’s protests to stand.

Malarcher was bothered by what he saw as a growing lack of sportsmanship in the game as well as what he saw as mismanagement of the league. The events in the final game of the series against the Stars were the breaking point for him. He wrote a letter to the sports editor of the Chicago Defender (which published it on January 19, 1935), in which he criticized the commissioner for his lack of action regarding the incidents in the final game of the 1934 championship series.34

Malarcher decided it was time to leave professional baseball and tendered his resignation with a 12-page letter to Robert Cole in mid-February of 1935. Asked why he was resigning, Malarcher simply responded, “I like baseball and I always will, but I think the time is here for me to step out.”35 He was only 39 years old when he walked away from a successful managerial career.

After leaving baseball, Malarcher worked as a real estate broker for several decades. He briefly returned to the American Giants as their business manager in 1940 but stayed in the position for only one year.36 Malarcher’s wife, Mabel, died in 1946; the couple did not have any children. The death of his wife inspired Malarcher to begin to write poetry, an avocation he continued to practice for the remainder of his life. In 1948 Malarcher wrote a poem, “Sunset Before Dawn,” after he had attended a game and watched former Negro League players who were now playing in the White major leagues. Malarcher described the poem as concerning “the host of Negro players, now deceased – the great ones whom the great majority of America’s fans did not see.”37

Sunset Before Dawn

By David MalarcherThou wert among the best

Who wrought upon this earth,

O dead! Thine endless rest

Is merit of thy worth …O, minds of fleetful thought!

O dead who lived too soon!

What pity thou wert brought

To twilight ere the noon!But sleep thou on in peace,

As orchids which did bloom,

Like pure unspotted fleece

Within the forest’s gloom.

In 1978, when Malarcher was a member of the Society for American Baseball Research, he published a paean to Oscar Charleston in SABR’s Baseball Research Journal.38

For the remainder of his life, Malarcher lived in the same home he had built in 1927 at 6441 Vernon Avenue and attended Woodlawn A.M.E. Church in Chicago. “Gentleman Dave” Malarcher died at the age of 87 on May 11, 1982, in Chicago.39 He was buried in Saint James Methodist Cemetery in Convent, St. James Parish, Louisiana.

Sources

Unless otherwise noted, Seamheads.com was used for all Negro League player statistics and team records.

Thanks are extended to Cassidy Lent, manager of reference services at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Library, for providing a copy of David Malarcher’s Hall of Fame player file.

Notes

1 “Malarcher, Ideal Leader, Quits Baseball For Good,” Chicago Defender, February 16, 1935: 17.

2 John Holway, Voices From the Great Black Baseball Leagues, Revised Edition (New York: Da Capo Press, 1992), 41-42.

3 Holway, 44.

4 Paul Debono, The Indianapolis ABCs (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 1997), 66.

5 Holway, 44-45.

6 Debono, Indianapolis ABCs, 74.

7 Steven R. Greenes, Negro Leaguers and the Hall of Fame (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2020), 188.

8 Debono, Indianapolis ABCs, 80-82.

9 From survey found in Malarcher’s Hall of Fame player file.

10 Debono, Indianapolis ABCs, 82.

11 Paul Debono, The Chicago American Giants (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2007), 71.

12 From survey found in Malarcher’s Hall of Fame file.

13 Debono, Chicago American Giants, 77.

14 Debono, Chicago American Giants, 87.

15 “The Game Play by Play,” Chicago Defender, August 26, 1922, 10.

16 Debono, Chicago American Giants, 96.

17 From contract found in Malarcher’s Hall of Fame file.

18 Debono, Chicago American Giants, 108.

19 From contract found in Malarcher’s Hall of Fame file.

20 Debono, Chicago American Giants, 110.

21 Debono, Chicago American Giants, 111-114.

22 Debono, Chicago American Giants, 118-119.

23 Debono, Chicago American Giants, 120-121.

24 “D. Malarcher Threatens to Quit Giants,” Chicago Defender, April 13, 1929: 8.

25 Debono, Chicago American Giants, 126.

26 Debono, Chicago American Giants, 128.

27 Bidwill later owned the Chicago Cardinals of the NFL.

28 Debono, Chicago American Giants, 130.

29 Debono, Chicago American Giants, 132.

30 Debono, Chicago American Giants, 133.

31 Debono, Chicago American Giants, 135.

32 Larry Lester, Black Baseball’s National Showcase (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2001), 61.

33 Debono, Chicago American Giants, 137.

34 Dave Malarcher, “Chicago Hits Ruling by Baseball Head on Protest,” Chicago Defender, January 19, 1935: 17.

35 “Malarcher, Ideal Leader, Quits Baseball for Good,” Chicago Defender, February 16, 1935: 17.

36 “Malarcher Becomes Business Manager of American Giants,” Chicago Defender, May 18, 1940: 24.

37 Holway, 57.

38 David J. Malarcher, “Oscar Charleston,” Baseball Research Journal (Cooperstown, New York: SABR, 1978), 68.

39 David Malarcher obituary, Chicago Tribune, May 14, 1982: C27.

Full Name

David Julius Malarcher

Born

October 18, 1894 at White Hall, LA (USA)

Died

May 11, 1982 at Chicago, IL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.