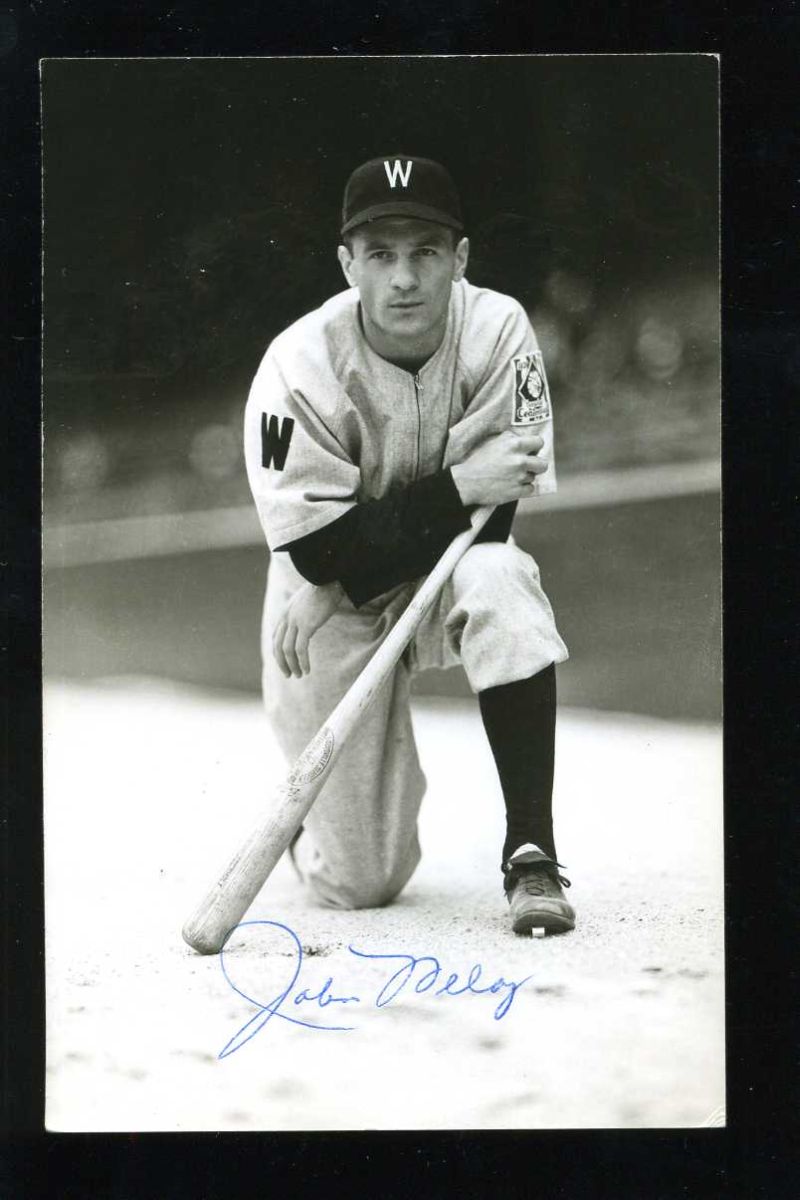

Johnny Welaj

In the 1970s, three decades after his four-year major-league playing career had come to an end Johnny Welaj (pronounced “WELL-eye”) wrote to author Harrington E. Crissey Jr. to reminisce. “It was great to be associated with [Philadelphia Athletics manager] Connie Mack,” he said. “There are not enough good things that baseball can say of him. He . . . w[as] baseball itself.”1 Being an ambassador for “baseball itself” Welaj, a favorite of fans and owners alike, spent seven decades in the profession as a player, coach, manager, and front office executive. “[L]acking a greater chance to show his stuff” during his playing career, he hung around the sport long enough to earn the title of a “baseball-lifer.”2

In the 1970s, three decades after his four-year major-league playing career had come to an end Johnny Welaj (pronounced “WELL-eye”) wrote to author Harrington E. Crissey Jr. to reminisce. “It was great to be associated with [Philadelphia Athletics manager] Connie Mack,” he said. “There are not enough good things that baseball can say of him. He . . . w[as] baseball itself.”1 Being an ambassador for “baseball itself” Welaj, a favorite of fans and owners alike, spent seven decades in the profession as a player, coach, manager, and front office executive. “[L]acking a greater chance to show his stuff” during his playing career, he hung around the sport long enough to earn the title of a “baseball-lifer.”2

John Ludwig Welaj Jr. was born on May 27, 1914, the eldest of five children of Polish immigrants John Ludwig Welaj, Sr. and Catherine Mastalska (Steffas) Welaj, in Cambria County, Pennsylvania, 80 miles east of Pittsburgh. His parents arrived in the United States separately around the turn of the century and married in Ebensburg, Pennsylvania, on June 2, 1913. After briefly relocating northwest of Philadelphia, the family moved to the borough of Manville, New Jersey, 40 miles southwest of New York City, where John, Sr. went to work for Johns Manville Corporation, an asbestos manufacturer.

Johnny grew up among talented and athletic siblings. His second eldest brother Walter spent one year in Class-D ball before pursuing a lengthy career as a minor-league umpire. In 1942, Louis, the youngest brother, launched his own professional career culminating with five years of Triple-A ball in the Brooklyn Dodgers organization. Afterward, Louis sought out a career in politics and in 1957 was elected mayor of Manville.3 But in the athletic field these siblings simply followed the path established by their older brother. Attending Bound Brook High School in the neighboring borough of Bound Brook, New Jersey, Johnny was a standout athlete in football, basketball, and especially baseball. After graduating from high school in 1934, Welaj continued his diamond success on the semi-pro sandlots.

Washington Senators scout Joe Cambria discovered Welaj there in 1936. The owner of several minor-league teams, Cambria signed the 22-year-old right-handed hitter and assigned him to his Class-A club in the New York-Pennsylvania League. (Welaj also played two games with the franchise’s highest minor league affiliate, the Class-AA Albany (New York) Senators in the International League.) Though the club split the season between York, Pennsylvania, and Trenton, New Jersey—presumably for financial reasons—the shift did not affect Welaj’s performance. He led the club in hits (171), doubles (30), and triples (11—tied with fellow outfielder Edward Remorenko) while placing among the league leaders with a .339 average in 505 at-bats.

Though a promotion would seem appropriate for Welaj after production like this, the Senators, after parting with its Double-A affiliate following the 1936 season, had few options available. Then on April 4, 1937, acquisition of perennial All Star Al Simmons crowded Washington’s veteran outfield and effectively blocked any potential of Welaj’s jumping to the majors. Thus he spent the 1937-38 seasons patrolling the outfield for Cambria’s Trenton Senators.

During the 1938-39 offseason, following the club’s fourth second-division finish in five years, the Senators traded outfielder Fred Sington and sold Simmons as part of a massive youth movement. Welaj would be one of 20 Senators who either exceeded their rookie status or made their major-league debut during the 1939 season. In spring training, he battled unsuccessfully with 28-year-old rookie Bobby Estalella for the starting left field job. Beginning the season on the bench, on May 2, 1939, Welaj made his major-league debut in St. Louis’s Sportsman’s Park as a defensive replacement for right fielder Taffy Wright. In two plate appearances Welaj struck out and walked. Nicknamed “Legs” for his lightning speed, Welaj stole second following the walk and came around to score in the Senators 9-7 win over the St. Louis Browns. The next day he collected his first major-league hit, a pinch-hit RBI single that helped the team beat the Browns again, this time in an 11-10 slugfest.

On May 5, Welaj earned his first start in right field. With Estalella struggling at the plate (.160 in his first 25 at-bats), three days later he moved over to left. On May 24, Welaj collected his first extra-base hits, two doubles, and drove in four runs in a 16-6 romp over the Browns. When Estalella’s bat came alive in June the Senators began rotating Welaj in a five-player platoon throughout the outfield. Starting in centerfield on July 2, he collected career high marks in hits (four) and RBIs (six) in leading the Senators to a 13-2 win over the Athletics. When the Nats visited New York two days later, a day best remembered as Lou Gehrig Day, hundreds of Welaj’s friends, relatives, and neighbors travelled from Manville to Yankee Stadium to celebrate Johnny Welaj Day before the first game of the scheduled doubleheader. It was only after the proceeding began “that Welaj was notified that Lou Gehrig would be giving his retirement speech in between games.” 4

Over a two-week period beginning July 8, Welaj went 11-for-31 with three doubles, a triple, seven RBIs, and eight runs scored. Oddly, this surge “earned” him a demotion to Class-A Springfield (MA) Nationals in the Eastern League (the Cambria-owned club which had transferred from Trenton in 1939). Frequently complemented for his aggressive play, Welaj “did not have the saving grace of power in his bat” so desperately needed by the offensively impaired Senators who were dead last in the league in runs scored and in the entire majors in home runs.5

His stay in Springfield proved short-lived. On August 17 Commissioner Kenesaw Landis, who was embroiled in a dispute with Cambria over the latter’s financial records, ordered Welaj and first baseman Bob Prichard back to the Senators (Prichard had been demoted two weeks before Welaj). Though the dustup between Landis and Cambria was quickly resolved, Welaj stayed with the parent club while Prichard returned to Springfield,. On September 10, in the middle of an eight-game hitting streak, he got his first major-league home run, a two-run shot in Yankee Stadium against New York left-hander Marius Russo in the Senators 4-3 loss. Welaj finished the season with a .274/.318/.363 slash line in 201 at-bats. His 13 stolen bases trailed only George Case’s league pacing 51 thefts for the club lead.

Washington’s offseason acquisition of slugger Gee Walker, combined with the move of third baseman Buddy Lewis to the outfield, once again made for a crowded field in 1940. A month into the season, Welaj was used exclusively in pinch-hitting and pinch-running situations. Given the opportunity to play in May after Lewis temporarily returned to the infield, Welaj set off on a blistering 16-for-44 pace that included a May 26 walk-off, game winning inside-the park homer against Athletics right-hander George Caster. “Welaj belongs in the regular lineup,” wrote Sporting News contributor Denman Thompson. A second surge (12-for-30 through June 8) bolstered the contention. But then Welaj fell into a 2-for-28 slump, and quickly returned to a reserve role. He got just 66 at-bats over the second half of the season.

Despite a strong 1941 spring training, Welaj played even less. Of his 49 appearances, 31 came as a pinch-hitter or pinch-runner. On December 13, the Senators traded Welaj and left-hander Ken Chase to the Boston Red Sox for right-hander Jack Wilson and centerfielder Stan Spence. The Red Sox had been anxious to acquire a lefty after southpaw hurler Mickey Harris was called into active military service two months earlier. Welaj and Spence were ancillary components to a trade of pitchers.

Bolstered by a strong start in the Red Sox 1942 spring training, Welaj was initially projected to platoon in the outfield with veteran Lou Finney. But in the latter weeks of grapefruit league play, as Welaj began spending more time on the bench, his frustration boiled over. Days before the start of the regular season, Welaj told Red Sox skipper Joe Cronin: “I don’t want to play for you!” “Go see [general manager] Eddie Collins,” Cronin shot back. 6 Welaj went to Collins’ office where the GM invited him to arrange his own trade. On April 13, 1942, a day before the start of the new season, Welaj was sold to the Yankees. Promised a quick return to the majors, he accepted an assignment to the Double-A American Association’s Kansas City Blues after Blues outfielder Eric Tipton suffered a broken ankle. A month later, after seeing little play and no signs of a promotion, Welaj was sold to the International League’s Buffalo Bisons (the Detroit Tigers Double-A affiliate).

Finally offered an opportunity for regular play, Welaj opened at a .340 pace before he was sidelined with a pulled leg tendon. “I’m going back to the American League or bust both legs trying,” he declared upon his return to the lineup.7 In one plate appearance in July, Welaj reached base and stole second, third and home in route to a club-leading 30 thefts. Selected to the circuit’s All Star team, he finished the season among the team leaders in nearly every offensive category including a career best 11 home runs. Welaj also placed among the league leaders with a .309 average. On November 2, the Athletics selected him in the rule 5 draft.

Welaj was one of several players the A’s acquired during the offseason as the club filled roster vacancies of those who were drafted or enlisted in the military during the Second World War. One such player was Estalella, who came to the team in a March 21, 1943, trade with the Senators. No fewer than 11 players took the outfield from the Athletics’ patchwork roster during the 105-loss season, a disastrous season that included a then-league tying record 20 straight losses. 8 Throughout this woeful season the speedy Welaj was a favorite of Athletics manager Connie Mack. He stole a dozen bases to tie with outfielder Jo-Jo White for the team lead, in only about half as many at-bats. Despite his sporadic playing time Welaj “ hustled, gave it all [he] had, and never complained, grateful to be back in the bigs” 9 But on September 27, six days before the end of the season, the Athletics traded Welaj and infielder Eddie Mayo to the Red Sox for 24-year-old right-hander Norm Brown and an undisclosed amount of cash. Welaj did not appear with Boston. He finished the season with career high marks in appearances (93), at-bats (281), hits (68), runs (45) and total bases (86).

In 1940, Welaj had married Iowa native Pauline Gertrude Smith in Washington, D.C. Seven years earlier Pauline, who was just four months younger than Welaj, had moved to the nation’s capital to attend the Washington School for Secretaries before launching a long career with the Veterans Administration. Sometime after they married the couple moved to Cedar Rapids, Iowa, Pauline’s hometown. On October 12, 1943, they welcomed their only child, a daughter named Janet. The next day Welaj received notice of his induction into the US Army.

Citing the birth of his newborn, Welaj successfully secured a two-month delay to spend time with his daughter. He entered the service on December 21, 1943, and spent most of his 25 months in service overseas where he earned two battlefield stars in the Pacific Theater. In 1945, while serving as a sergeant with the Fifth Replacement Depot in Oro Bay, New Guinea, Welaj played baseball alongside Morrie Arnovich, a National League outfielder, Vincent DiBiasi, “a Yankees’ farmhand, [and] Denn[is] Horton, a Tigers’ farmhand. The team remained together when the Depot was transferred to the Philippines later in the year.” 10 On January 4, 1946, four months following Japan’s official surrender, he was discharged from the service.

Returning to Organized Baseball, Welaj was assigned to the Red Sox Triple-A affiliate in Louisville, KY. One of four fulltime players with a .300 average, Welaj helped pace the Colonels to a 92-win first place finish while placing among the American Association leaders in hits (172), runs (108) and triples (10). He also led the league with 37 stolen bases. On October 1, in Game Four of the Junior World Series, Welaj collected four hits to lead the Colonels to a 15-6 win over the Montreal Royals. Louisville’s chances of returning to the Series in the following year, 1947, received a blow in September when Welaj, who was once again pacing the team leaders in most offensive categories, suffered a broken hand in the playoffs.

In 1948, Welaj was traded to the Triple-A Toronto Maple Leafs in the International League for what he recalled was a sizable package consisting of minor leaguer “Matt Bates, [outfielder-pitcher] Cot Deal and $50,000.” 11 He drew some consideration for the circuit’s MVP after hitting .315 and sharing the stolen base crown with future NL Rookie of the Year Sam Jethroe. But by the next season injuries began to take a toll on the aging veteran. On June 27, 1949, Welaj tore cartilage in his right knee and consequently missed about a third of the season. Groin injuries, an unspecified hand injury, and other nagging ailments would limit him to a reserve role for the rest of his playing career.

In May 1950, Welaj was united with his brother Louis when the Maple Leafs traded him to the Montreal Royals for infielder Bobby Rhawn. Moreover, the trade introduced Welaj to Royals manager Walt Alston. The future Hall of Fame skipper considered Welaj the ultimate team player, and during their two years together Alston began steering him toward a managerial career. In 1954, Welaj signed with the Triple-A Havana Sugar Kings as a player-coach and eventually took over as the interim traveling secretary when the regular secretary took ill. “It was what you might call baseball in the raw,” Welaj said in recalling his experience in Cuba. “The fans really have a good time. They bring drums and instruments into the ballpark and anytime the home team does anything, they pound on those drums.” 12

During Welaj’s time in Washington he had cultivated a close relationship with Senators owner and future Hall of Famer Clark Griffith. In January 1955, at Griffith’s strong urging, Welaj accepted the job as manager of the club’s Class-B affiliate in Hagerstown, MD, in the Piedmont League. “Work your way up,” Griffith told him. “Some day you may get a crack at the big club.” 13 When the Piedmont League folded after the 1955 season, Welaj took over the Class-D Erie (PA) Senators in the Pennsylvania-Ontario-New York League. In what proved to be his last stint as a professional player, Welaj inserted himself into 35 games including one as a pitcher (he had also pitched one game with Trenton 19 years earlier). In 1957, Welaj moved to Texas to run the Class-B Midland/Lamesa Indians in the Southwestern League. But in June, a cost cutting measure forced the club to replace him with first baseman Hank O’Neal. During his three years as a minor league manager Welaj served as the first professional manager for future big leaguers Bob Allison and Sandy Valdespino. And to his advantage, the Spanish he had learned in Havana proved useful with seven Cuban players on the Midland/Lamesa roster.

In the 1930s Welaj had attended Rider College in Trenton, New Jersey, where he studied banking and business. Beginning in 1957, this education proved useful when he moved into the Senators front office as director of sales and promotions. In this capacity Welaj spoke frequently on the rubber chicken circuit. One winter Welaj travelled to Germany with Hall of Fame catcher Mickey Cochrane and Senators vice-president and former hurler Joe Haynes to help conduct a three-day clinic for military personnel stationed overseas. When the franchise moved to Minnesota in 1961, Welaj remained behind and resumed the same sales and promotions responsibilities for the expansion Washington Senators. In 1962 he added advertising to his growing list of responsibilities. Ten years later, he moved with the team to Arlington, Texas, where he served as the Rangers director of stadium operations until his retirement as a fulltime employee in 1984. But over the next 15 years Welaj continued to serve as the “Rangers spring training director coordinating logistics and tickets sales in Pompano Beach and Port Charlotte, Florida. He was ‘a fixture in this organization,’ said Rangers Vice President of Communications John Blake[,] ‘the type of person who would also help out and offer a smile and a kind word.’”14 Around 2000, Welaj was affiliated with the Philadelphia Athletics Historical Society, and three years later, he was inducted into the Bound Brook High School Alumni Association Hall of Fame.

On September 13, 2003, four months after his 89th birthday, Welaj died at the Autumn Leaves of Arlington Assisted Living Center in Arlington, Texas. Preceded in death by his wife Pauline eight years earlier, he was survived by his daughter Janet. Welaj was buried at Moore Memorial Gardens in Arlington.

“I’ve been associated with baseball for [more than 60] years, and the game as a whole has been very good to me,” Welaj said.15 Over his four-year major league career Welaj managed to achieve a meager .250/.298/.323 slash line with 36 stolen bases in 793 at-bats. His impact on the game as a manager, coach, and front office executive for many years after was his real testament.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted Ancestry.com and Baseball Reference.com. The author wishes to thank SABR members Bill Mortell for his valuable research assistance and Tom Schott for review and edit of the narrative.

Notes

1 Harrington E. Crissey Jr., Teenagers, Graybeards and 4-F’s, Volume 2: The American League (Self-Published, 1982), 128.

2 “Kansas City’s Hope High With 3 Players Added,” The Sporting News, April 16, 1942: 3.

3 One source indicates that the third brother Anthony also played professionally, a claim the author was unable to substantiate.

4 N. Diunte, “July 4, 1939 was also Johnny Welaj Day at Yankee Stadium,” Baseball Happenings. Accessed February 13, 2017 (http://bit.ly/2kiOwur ).

5 “Two Shakes and Presto! New Washington Lineup,” The Sporting News, December 18, 1941: 5.

6 Brent Kelley, The Pastime in Turbulence: Interviews with Baseball Players of the 1940s (Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland Publishing, 2001), 35.

7 “Welaj Speedy on Paths,” The Sporting News, November 12, 1942: 5.

8 A dubious honor now held by the Baltimore Orioles who lost 21 straight in 1988.

9 Norman Macht, “Connie Mack and Wartime Baseball—1943,” 2013 The National Pastime. Accessed February 12, 2017 (http://bit.ly/2l2YiAl).

10 Gary Bedingfield’s Baseball in Wartime, “Baseball’s Greatest Sacrifice: Morrie Arnovich,” March 12, 2007. Updated March 27, 2010. Accessed February 13, 2017 (http://bit.ly/2kiKdiQ).

11 Kelley, Pastime in Turbulence, 36.

12 Ted Battles, “Cubans on the Field & Johnny Welaj,” Midland Baseball 1956-57. Accessed February 13, 2017 (http://bit.ly/2kZaGiI).

13 Ibid.

14 Baseball Almanac, “Johnny Welaj Stats.” Accessed February 13, 2017 (http://bit.ly/2lAm8UK).

15 Crissey Jr., Teenagers, Graybeards, and 4-F’s, 128.

Full Name

John Ludwig Welaj

Born

May 27, 1914 at Moss Creek, PA (USA)

Died

September 13, 2003 at Arlington, TX (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.