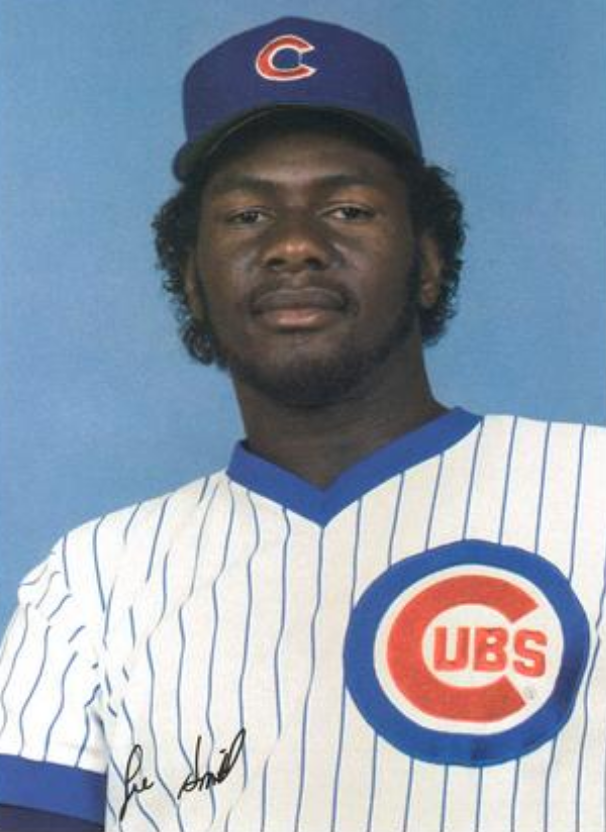

Lee Smith

With the game in the balance, Lee Smith would walk ever so slowly1 from the bullpen to the mound. The 6-foot-6, 250-pound Louisianan was in his time one of the most feared relief pitchers in the game.2 In his 18 major-league seasons (1980-1997), the right-hander pitched for eight different teams, and his records are notable for endurance and consistency.3 He’s the Chicago Cubs’ career saves leader (160); he also held the St. Louis Cardinals record for 13 seasons.4 When he retired after the 1997 season, he was the major leagues’ career saves leader (478). As of 2018, when he was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame, he still ranked third behind Mariano Rivera (652 saves) and Trevor Hoffman (601).

With the game in the balance, Lee Smith would walk ever so slowly1 from the bullpen to the mound. The 6-foot-6, 250-pound Louisianan was in his time one of the most feared relief pitchers in the game.2 In his 18 major-league seasons (1980-1997), the right-hander pitched for eight different teams, and his records are notable for endurance and consistency.3 He’s the Chicago Cubs’ career saves leader (160); he also held the St. Louis Cardinals record for 13 seasons.4 When he retired after the 1997 season, he was the major leagues’ career saves leader (478). As of 2018, when he was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame, he still ranked third behind Mariano Rivera (652 saves) and Trevor Hoffman (601).

A daunting sight was watching Smith throwing “pure gas from the shadows” when Wrigley Field didn’t have lights.5 “You didn’t want to face him in the shadows because you really couldn’t see the ball that well,” remembered former pitcher Steve Stone, who watched Smith from the TV booth.6

Then there was Smith’s scowl. Jay Johnstone, a teammate on the 1984 Cubs, once asked the fierce-looking reliever, “Hey, Lee, why bother washing your car? Just glare at it and the dirt will fall off!”7 (But Chicago newspaper columnist Mike Royko wrote that he liked Lee because his scowl seemed to say being a Cub caused him deep anguish.8)

Smith logged 11 seasons with 30 or more saves. His lifetime save percentage was 82%, in the middle of the pack among the 50 closers with the most saves. He led the National League in saves three times – once with 47 –and the American League once. Smith had a career record of 71-92 and 3.03 ERA, with 486 walks and 1,251 strikeouts in 1,289 innings pitched.

Lee Arthur Smith was born to Willie and Bessie Smith on December 4, 1957, in Jamestown, Louisiana, in the northern part of the state.9 In his youth he enjoyed hunting, fishing, and swimming. On Sundays, he played the guitar at services in the Ebenezer Baptist Church.10 His family made a living hauling pulpwood. If you asked him his favorite sport, he would have said basketball in a second. Baseball? No way.11

During his boyhood Lee endured experiences that shaped his view of the world. He awoke at 5:30 A.M. to catch a bus that passed three all-white schools on the way to his all-black school. After Louisiana integrated its schools in 1969, when he was 11, he crossed picket lines of protesting students and parents to arrive for class. The segregationist feeling died hard: Six times in his senior year at Castor High School, all-white schools forfeited basketball games rather than compete against a team with a black player.12

One day in his junior year of high school, as he walked across the outfield of a softball field during practice, a ball rolled to his feet, beyond the outfielders. Lee picked it up and heaved it to home plate. After the softball coach witnessed this, Smith was switched from the softball team to the baseball team.

“My brother and I used to throw little plum peaches that grew on our property by our mailbox. We tried to hit the flag on the mailbox. I guess that is why I have always had pretty good control,” Smith also later noted.13

A high-school senior in 1975, Smith planned to play basketball at Northwestern State Louisiana in Natchitoches, 50 miles from Jackson.14 But in June the Cubs drafted him in the second round of the free-agent draft, at the recommendation of former Negro League player and scout Buck O’Neil.15 (When he was called up to the Cubs in 1978, Smith became the last player drafted by the Wrigley ownership to make the major leagues.)

After being drafted, Smith sought out former major-league slugger Joe Adcock, who lived in nearby Coushatta, for advice. “Are you going to Northwestern to play basketball or get an education?” Adcock asked Smith.

“An education,” Smith told him.

Adcock’s advice: “Go (to Northwestern State) unless (the Cubs) offer you $50,000.” Smith was startled by the figure. But when O’Neil paid a visit to get his name on a contract, Smith asked for a $50,000 bonus and $8,000 for his education. To his surprise, O’Neil obliged. Smith regretted asking for so little, “I should have asked for $80,000!” he said later.16

Smith figured he could play for two years to qualify for the full bonus, then return home to haul pulpwood. “Those first few years, I made more money in pulpwood than in baseball,” he said. “That signing bonus was what kept me in it. I was going to play two years and then come back to the thickets.”

The Cubs assigned Smith to the Gulf Coast Rookie League. The next season he was promoted to Pompano Beach in the Class A Florida State League. After two seasons, mostly as a starter, he opted to continue in baseball rather than the wood business. By his fourth season he was at Double-A Midland (Texas League), throwing a blazing fastball but walking large numbers of batters, a habit that made a return to the thickets a possibility. But in 1978 Cubs minor-league pitching coach Randy Hundley moved Smith to the bullpen. 17

Smith resisted the move and briefly played basketball at Northwestern State.18 “Billy Williams (Cubs coach and Hall of Famer) came to my house. I can’t tell you in public what he said to me, but he convinced me to come back and play baseball,” Smith told a biographer.19

Smith returned to Midland as a reliever in 1979.20 (“The opportunity to pitch every day and be the ‘stopper’ became a thrill,” he said after a few years as a closer.21) In 1980 Smith was promoted to Triple-A Wichita, and was among the league leaders in saves.22 For his efforts, he earned a September call-up to Chicago.23

When Smith made his major-league debut on September 1, 1980, there was a shortage of optimism at Clark and Addison – the Cubs had the worst record in the National League.24 Bill Jauss of the Chicago Tribune wrote: “The Cubs celebrated Labor Day like most of the nation’s labor force Monday – by taking the day off, losing to Atlanta.” A sparse crowd at Wrigley Field cheered the big 22-year-old rookie when he retired the dangerous Dale Murphy on a chopper and fanned Glenn Hubbard. “Smith was the bright spot,” said Cubs manager Joey Amalfitano. “He’ll be out again.”25

A year later, on August 29, 1981, Lee whiffed Reggie Smith of the Los Angeles Dodgers to log his first major-league save. Joe Goddard of The Sporting News observed that the Cubs had “found relief in relief.”26 In his first two major-league seasons, Smith was 5-6 with one save.27

After the Wrigley family sold the Cubs to the Tribune Company,28 Dallas Green became the Cubs general manager and hired Lee Elia to manage the team.29 At the beginning of the season Elia used Smith in a set-up role “to keep his feet on the ground.”30

Future Hall of Famer Ferguson Jenkins befriended Smith and helped him with the art of pitching. Pitching coach Billy Connors showed him how to throw a slider to set up his fastball and suggested that Smith push off the mound with the ball of his foot rather than his heel. Connors observed: “He has a sound delivery, and he knows the hitters.”31

In 1982 Smith was 17-for-18 in save opportunities, establishing career highs in appearances (72) and innings pitched (117).

The Cubs commenced the 1983 season on a losing note.32 The nadir came early, in late April against Los Angeles. Smith entered the game and uncorked a wild pitch to allow the eventual game-winning run to score. Chicago plummeted to 5-14 in the National League East standings.33 The Cubs left the field to the taunts of fans behind the third-base dugout. Players had to be restrained from climbing onto the dugout roof to pursue them. The irate Elia, in one of his most notorious postgame rants, told reporters, “About 85 percent of the world is working. The other 15 percent come out here!”34 Elia later apologized but his diatribe would be a contributing factor in his being fired before the end of the season.35

Despite these distractions, Lee Smith thrived in the closer role, perhaps with the exception of his inaugural All-Star Game appearance, when he gave up two runs in the eighth inning as the American League scored a record 13 runs. 36

Still, Smith had his admirers. “There’s no doubt in my mind he’s the hardest thrower in the game,” said Cubs catcher Jody Davis. Catching Smith “was scary, very scary!” said Keith Moreland.37 Dusty Baker of Los Angeles admitted, “I don’t run from anybody, but the opinion around the National League is that you’re in no real hurry to get to him.”38

In 1983, when Smith posted an NL-high 29 saves, he was the co-winner (with the Phillies’ Al Holland) of The Sporting News Fireman of the Year honors.39 After the season Smith was re-signed to a five-year contract. Meanwhile GM Green engineered multiple trades to bolster the organization.

Green’s changes seemed to be paying off. On June 23, 1984, the Cubs were just 1½ games out of first place as they hosted St. Louis on the nationally televised Saturday afternoon Game of the Week on NBC.40 The packed Wrigley Field crowd thrilled as Ryne Sandberg smacked two game-tying home runs off former Cubs closer Bruce Sutter. Smith earned the extra-inning victory and Chicago went 59-34 for the remainder of the season.41

If Sandberg’s heroics seemed unreal, Cubs fans discovered that their 1984 team was for real by August 2. That day saw the “Immaculate Deflection,” when Pete Rose of Montreal hit a liner off Smith’s shoulder that resulted in a game ending double-play.42

Smith earned a save at Busch Stadium in St. Louis, on Sunday, September 23, when Chicago clinched a tie for the NL East, which they captured the next evening. Acquired from Cleveland in mid-June, Rick Sutcliffe pitched a complete game for his 16th victory since the trade. “That 1984 year was awesome,” said Smith. “I still remember the game in Pittsburgh when Rick Sutcliffe clinched it.”43

Smith was reliable but not as sharp as the previous year. He finished the 1984 regular season with a 9-7 record and 33 saves.44

Smith earned what turned out to be his only postseason save in Game Two of the National League Championship Series against San Diego, and the Cubs led the best-of-five series, two games to none. Excitement reigned among Cubs fans; their team was only one win away from its first World Series appearance since 1945.

The Padres won Game Three. The Cubs tried again in Game Four, at San Diego’s Jack Murphy Stadium. In the bottom of the ninth, with the score tied, the Padres’ Steve Garvey clubbed an opposite-field two-run home run off Smith to drive the Padres to a dramatic 7-5 victory.

“I tried to forget about it as soon as possible, because I don’t linger on things,” Smith recalled of the tough playoff loss. “I don’t regret the pitches I threw. I would try them again. Garvey is human; he can hit or miss. But the weird thing about that is the thing everybody remembers about me. The whole year wasn’t good for me because of injuries. It really hurts me career-wise, because I didn’t have to go out there. But I went out for the team, there are very few team players anymore.”45

The next afternoon, the NL pennant slipped out of the North Siders’ hands in almost literal fashion when first baseman Leon Durham misplayed a key groundball. The series loss was another harsh disappointment for Cubs fans and the franchise nicknamed the “lovable losers” – at least until they won the World Series in 2016, breaking a 108-year drought.

The following season was a fourth-place hangover for the Cubs. On September 8 at Wrigley Field, Smith struck out Pete Rose, back with Cincinnati, as Rose prepared to eclipse Ty Cobb’s record for hits. 46 Afterward Smith said, “It really wasn’t a good fastball and Pete was out in front of it.”47

Smith fanned a career-high 112 batters in 1985 and four times he struck out a career-high five batters.48 The following year, Smith did not walk a batter in 40 of his 66 appearances, shut out the opposition in 45 games, retired the first batter 70 percent of the time,49 and held opponents scoreless in 73 percent of his appearances.50

“Smitty pitched more innings last year because we couldn’t get our starters that far along,” said manager Gene Michael, who replaced Jim Frey at midseason in 1986. “If we keep Smitty’s innings short, I can get more out of him than using him in those three-inning stints. Three-inning stints kill a good reliever. Power pitchers, especially.”51

In the All-Star Game on July 14, 1987, at Oakland, Smith struck out four batters and earned the NL’s extra-inning victory. He became the last NL pitcher to fan four batters in an All-Star Game until Zack Greinke did it in 2015.52

In 1987 Smith became the second reliever to have four consecutive 30-save seasons. (Dan Quisenberry was the first.) But he also had 12 blown saves and was booed routinely by Cubs fans. Chicago sank to last place and Dallas Green resigned. “I would have been a hell of a lot better pitcher,” a petulant Smith commented, “if they had allowed me to throw the curveball that Fergie [Jenkins] taught me, it would have been great. He taught me a nasty curveball. But they said, ‘You don’t need another pitch.’ Yeah, Dallas knew a lot about pitching, he won 20 games, but it took him eight years to do it!”53

Frey resurfaced as the Cubs’ general manager, and Don Zimmer became the new manager.54 Smith acknowledged that his weight was causing him problems, and organizational discussions about his weight affecting his knees fueled a trade.55 Zimmer thought Smith’s knees wouldn’t last another season.56

“I can remember to this day what I said to Shawon Dunston,” Smith said. “The first sorry sucker to be traded is me, because I had a good year and I am not making much money. I was a prime candidate to get rid of.”57

At the winter meetings in December 1987, Frey traded Smith to Boston for pitchers Al Nipper and Calvin Schiraldi.58 Boston GM Lou Gorman accepted the offer and immediately held a press conference to announce the trade before it could be rescinded.59 “Our deal for Smith shook the whole (winter) meeting,” Gorman said. “Nobody believed we acquired Smith and gave up only Nipper and Schiraldi.” 60

“Frey told me: ‘Smitty, I will trade you, but I won’t take just anything for you,’” Smith said. “Next, he took the first two sorry guys they offered him.”61 Smith, perhaps rejuvenated by the trade, amassed nearly 300 saves over the next 10 seasons. 62

Smith said his time with the Cubs was fraught with unfulfilled dreams. If the trade, he said, “The only thing that ticked me off was that it took so long. I wanted to get traded from the Cubs after 1985 and go somewhere where I could win.”63

As of 2016 Smith was the all-time Cubs leader in saves (180), ranked third in games pitched (458) ,64 and from 1983 through 1987 averaged 32 saves per year.65

The Red Sox expressed no concern over Smith’s weight, and Boston won the American League East title in 1988 as Smith saved 29 games.66 “Boston would not have won the AL East this year without Lee Smith!” Gorman declared.67 But the Oakland Athletics swept Boston in three games in the American League Championship Series. Smith was ineffective as he lost the second game.68

The 1980s were the first decade in which one-inning closers came to the fore.69 Smith during the decade earned 234 saves and had four consecutive 30-save seasons. Jeff Reardon, meanwhile, collected 266 saves, had five straight 30-save seasons, and closed out Game Seven of the 1987 World Series with Minnesota. Reardon signed with Boston as a free agent in December of 1989. Smith, in the last year of his contract, threatened to leave Boston.

The Red Sox traded the 32-year-old Smith to St. Louis for outfielder Tom Brunansky on May 4, 1990.70 Smith wasn’t unhappy to leave but expressed some fondness for his time with the Red Sox. “Oh God, yeah, did I enjoy my time in Boston,” he said. “The club was unbelievable and we had some really good years.”71

The one-inning closer remained the star of the bullpen in the early 1990s.72 When Smith began closing games for the Cubs, 55 percent of his appearances were more than one inning. In his tenure at Boston, that number dropped to 42 percent. In St. Louis, just 17 percent of his appearances were for more than one inning.73

Smith reached his peak in his brief spell with the Cardinals. In two full seasons and parts of two others he averaged 45 saves per season and earned three consecutive All-Star berths. In 1991 he had 47 saves, a Cardinals record and his personal best, and won the NL Fireman of the Year Award. The next year he shared the award with Doug Jones of the Houston Astros.74 During 1993 Smith surpassed Reardon with save number 358. On August 31, with free agency approaching, Smith was traded to the New York Yankees for minor-league pitcher Rich Batchelor.75

Smith had no regrets about his stint with the Cardinals. “I played for my favorite manager in St. Louis, Joe Torre,” he told an interviewer. “You knew what he expected from you. He gave me one of my greatest compliments, ‘Lee Smith is one of two relievers I never had to worry about, and the other is Mariano Rivera.’ For me that was awesome!”76

But Smith was now 35 years old and had just two productive years left as a closer. After a month with the Yankees, he became a free agent at the end of the 1993 season and signed with the Baltimore Orioles. With Baltimore in 1994, he led the American League with 33 saves. A free agent again after that season, he signed with the Angels and racked up 37 saves in 1995. On May 27, 1996, the Angels traded Smith to Cincinnati for relief pitcher Chuck McElroy. Jeff Brantley held the closer role for the Reds and Smith became a set-up man. Released after the season, he signed with Montreal. He had an undistinguished 1997 season (5.82 ERA), and was released by the Expos after the season. After unsuccessful attempts to stay in the majors with Kansas City and Houston, Smith retired as a player in the spring of 1998.77

Smith exited baseball having made seven All-Star teams. In addition to his top ranking on the career saves list, he then led all relievers with 1,016 relief appearances and was only the fourth major-league pitcher to appear in more than 1,000 games.78

Within three years Smith was back in baseball as a coach in the San Francisco organization.79 He was a pitching coach for the South African team in the 2006 and 2009 World Baseball Classic.80 As of 2016, he was a roving scout for the Giants. His busy travel schedule also included baseball clinics for children.81 Smith and his wife, Cheryl, are the parents of twins, Nicholas and Alanna.82 He has three children from a previous marriage, Nikita, Lee Jr., and Dimitri.83

Smith’s pitching philosophy was straightforward. Asked if he should pitch to a hitter’s weakness or his own strength, Smith told an interviewer, “I would pitch to my strength. They’ll tell you that guys were good fastball hitters. Well, who wasn’t? But you couldn’t hit my fastball if I made the pitch where I wanted to make it. Plus I had nine guys on one.

“I’ll tell you, the toughest thing for me was pitching at home when you had two strikes on the last hitter. You try to stay within yourself and not overthrow. But you’ve got the fans cheering and yelling your name, and it’s hard not to overthrow. That’s why I took a lot of time between pitches. I wanted to get it right the first time. Just make sure that you don’t throw a pitch without a purpose. You hear people talk about wasting a pitch. I don’t do that. Every pitch had a purpose, and I stayed within myself. I had to do it right the first time. Even if a guy got a hit, as long as it was a pitch I wanted to make, okay. I never wanted to underestimate the hitter. But I didn’t give him a whole lot of credit, either.”84

Speaking about his prospects for Cooperstown in 2013, Smith talked about how far he had come on his journey. “I came from a small town known as Jamestown, Louisiana, and they still don’t even have a traffic light,” he said. “There were 26 people in my graduating class. Never did I imagine playing in 400 games, let alone dreaming of saving over 400 games. My greatest dream would be for the Hall of Fame to recognize my career. It would mean so much to me given my background.”85

In 2017, Smith’s 15th and final year on the Baseball Writers’ Association of America Hall of Fame ballot, he was favored by 34.2 percent of the writers, almost exactly the same as the 34.1 percent he received in 2016.

His election finally came in 2018, when he was a unanimous selection by the 16 members of the Today’s Game Era committee. He will be inducted into Cooperstown in the summer of 2019.

Last revised: December 10, 2018

Notes

1 Bob Vorwald, Cubs Forever: Memories From the Men Who Lived Them (Chicago: Triumph Books, 2008), 8.

2 Al Yellon, “A Game From Cubs History: April 29, 1983.” bleedcubbieblue.com/2013/1/26/3890354/cubs-history-game-april-29-1983; Jimmy Greenfield, 100 Things Cubs Fans Should Know & Do Before They Die (Chicago: Triumph Books, 2012), 59.

3 Bill James, The Bill James Gold Mine (Chicago: ACTA Sports, 2008), 234.

4 Terrance Harris, “Lee Smith Is Ranked No. 42 Among Louisiana’s All-Time Top 51 Athletes,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, July 3, 2014.

5 Bruce Nash and Allan Zullo, Baseball Confidential (New York: Pocket Books, 1988).

6 Vorwald, 8.

7 Bob Logan, More Tales From the Cubs Dugout (Champaign, Illinois: Sports Publishing, 2003), 23.

8 Mike Royko, The Chicago Tribune Collection 1984-1997 (Chicago: The Chicago Tribune, 2014).

9 Teddy Allen and John James Marshall, “The Other Lee Smith,” Chicago Tribune, July 26, 1987.

10 Ibid.

11 Ibid.

12 Mike DiGiovanna, “The Big Easy: Smith’s Laid-Back Personality Helps Him Become One Mean Pitcher on the Mound,” Los Angeles Times, April 23, 1995.

13 Kevin Neary and Leigh A. Tobin, Closer: Major League Players Reveal the Inside Pitch on Saving the Game (Philadelphia: Running Press, 2013), 155-157.

14 David L. Porter, Latino and African American Athletes Today: A Biographical Dictionary (Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Publishing Group, 2004), 353.

15 Yellon.

16 Allen and Marshall.

17 Ibid.

18 Fred Jeter, “MLB icon Lee Smith almost had basketball career,” Richmond Free Press, January 29, 2016.

19 Vorwald.

20 Adam Zuvanich, “Time Spent in Midland Made Big Impact on Smith’s Career,” Odessa (Texas) American, August 29, 2012.

21 Fran Zimniuch, Fireman: The Evolution of the Closer in Baseball (Chicago: Triumph Books, 2010), ix.

23 Allen and Marshall.

25 Bill Jauss, “Cubs Take Another Day Off,” Chicago Tribune, September 2, 1980.

26 Porter, 353.,

27 Zimniuch, 110.

28 Sam Pathy and John Thorn, Wrigley Field Year by Year: A Century at the Friendly Confines (Champaign, Illinois: Sports Publishing, 2014).

29 Ibid.

30 Alan Ross, Cubs Pride: For the Love of Ernie, Fergie & Wrigley (Nashville: Cumberland House Publishing, 2004), 43.

31 Porter, 353.

32 Warren Wilbert and William Hageman, Chicago Cubs: Seasons at the Summit, the 50 Greatest Individual Seasons (Champaign, Illinois: Sports Publishing, 1999), 109.

34 Yellon; Jimmy Greenfield, 100 Things Cubs Fans Should Know & Do Before They Die (Chicago: Triumph Books, 2012), 59.

35 Wilbert and Hageman, 109.

36 Joseph Durso, “A Night of Long Hits and One-Liners,” New York Times, July 8, 1983.

37 Wilbert and Hageman, 108-109.

38 Wilbert and Hageman, 109.

40 Dan McGrath and Bob Vanderberg, 162-0: Imagine a Cubs Perfect Season: A Game-by-Game Analysis of the Greatest Wins in Cubs History (Chicago: Triumph Books, 2001).

41 Phil Barnes, “On This Day in 1984: The Sandberg Game,” Vine Line Magazine, June 6, 2015, vineline.mlblogs.com/2015/06/23/from-the-pages-of-vine-line-the-sandberg-game-changed-it-all/.

42 Bob Logan and Pete Cava, The Immaculate Deflection; Amazing Tales From the Chicago Cubs Dugout: A Collection of the Greatest Cub Stories Ever Told (Champaign, Illinois: Sports Publishing, 2012).

43 Fred Mitchell, Chicago Cubs – Where HaveYou Gone? (Champaign, Illinois: Sports Publishing; 2013), 206.

45 Mitchell.

46 Floyd Sullivan, “13 Best Wrigley Field Memories, No. 4: Pete Rose and Ty Cobb,” Chicago Now, August 13, 2014, chicagonow.com/waiting-4-cubs/2014/08/13-best-wrigley-field-memories-a-bakers-dozen-no-4-pete-rose-and-ty-cobb/.

47 Fred Mitchell, “A Tie for Rose, Reds, Cubs – Pete’s Even With Ty,” Chicago Tribune, September 9, 1985.

49 Porter.

50 Porter, 353.

51 Allen and Marshall.

52 Mark Sheldon, “MVP Trout Fuels AL’s Third Straight ASG Win; Greinke Grinds Through AL Lineup,” MLB.com, July 15, 2015. baseball-reference.com/allstar/2015-allstar-game.shtml.

53 George Castle, Where Have All Our Cubs Gone? (Lanham, Maryland: Taylor Trade Publishing, 2005), 177-178.

54 Adam Uirey, “Jim Frey,” SABR Baseball Biography Project, sabr.org/bioproj/person/1245e7ca.

55 Zimniuch, 110.

56 Peter Golenbock, Red Sox Nation: An Unexpurgated History of the Boston Red Sox (Chicago: Triumph Books, 2005), 428.

57 Lew Friedman, Game of My Life Chicago Cubs (Champaign, Illinois: Sports Publishing, 2012).

58 Zimniuch, 110.

59 Golenbock, 428.

60 Russ White, “Stoking Baseball’s Hot Stove Gathering Heats Up Trade Talk,” Orlando Sentinel, December 4, 1988.

61 Paul Sullivan, “Lee Smith Bitter About Return to Wrigley,” Chicago Tribune, June 20, 1990.

62 Ibid.

63 Friedman.

64 James Stacho, “History of the Best/Worst Cubs Trades,” AXS Entertainment/Sports/MLB, July 18, 2011. examiner.com/article/history-of-best-worst-cubs-trades.

65 Friedman.

66 Richard M. Russell, “A Brief History of the Boston Red Sox,” Lulu.com, July 23, 2011.

67 White.

68 Dan Flaherty, MLB History, Sports History Articles, thesportsnotebook.com/2014/11/1988-alcs-sports-history-articles/.

69 Dan D’Addona, “Baseball’s Forgotten Era: The ’80s,” SABR Baseball Research Journal, Fall 2011,

70 “Red Sox Deal Smith, Get Brunansky,” Los Angeles Times, May 5, 1990.

71 Jon Goode, “Close Up With the Ultimate Closer; Catching Up With Lee Smith,” Boston.Com, June 19, 2004.

72 William McNeil, The Evolution of Pitching in Major League Baseball (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company Inc., 2006), 98.

73 Neary and Tobin, 155.

74 Doug Feldmann and Steve Adams, St. Louis Cardinals Past & Present (Minneapolis: MVP Books, 2008), 93.

76 Neary and Tobin.

77 Shepard C. Long; Lee Smith, Baseballlibrary.com, baseballlibrary.com/ballplayers/player.php?name=lee_smith_1957.

78 Associated Press, “Reliever Lee Smith Retires From Expos,” Los Angeles Times, July 16, 1997, http://articles.latimes.com/1997/jul/16/sports/sp-13187. The list of pitchers with 1,000 appearances had expanded to 16 as of 2016.

79 Ibid.

80 Nick Friedell, ‘1984 Chicago Cubs – Where Are They Now?” ESPNChicago.com, http://espn.go.com/chicago/specialFeature?page=1984cubs.

81 Richard Gregory, “Pitching great Lee Smith shares words of wisdom with local ballplayers,” Danbury (Connecticut) News-Times, June 29, 2016.

82 Negron-Radachowsky Family Tree, information about Lee Arthur Smith, genealogy.com/ftm/n/e/g/Michael-L-Negron/WEBSITE-0001/UHP-0031.html.

83 Goode.

84 Zimniuch.

85 Neary and Tobin, 160.

Full Name

Lee Arthur Smith

Born

December 4, 1957 at Jamestown, LA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.