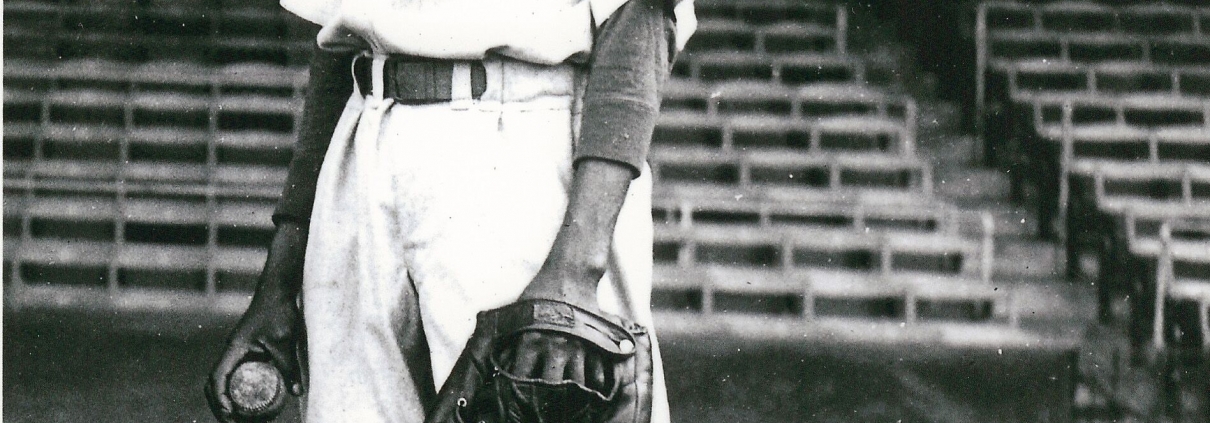

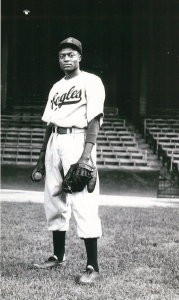

Leniel Hooker

Leniel Charlie Hooker was a right-handed pitcher from 1940 to 1948 with the Newark Eagles of the Negro National League. A 6-footer who weighed about 169 pounds, Hooker had a decent fastball and also threw a knuckleball. He was also considered a fair hitter and an excellent fielder.

Leniel Charlie Hooker was a right-handed pitcher from 1940 to 1948 with the Newark Eagles of the Negro National League. A 6-footer who weighed about 169 pounds, Hooker had a decent fastball and also threw a knuckleball. He was also considered a fair hitter and an excellent fielder.

Hooker was born on June 28 in Sanford, North Carolina, but the year is as foggy as some of the statistics from this time in history. Hooker put 1916 on his draft card, but his death certificate shows 1919, his Social Security Death Index shows 1921, and the 1930 Census lists Hooker — with his first name spelled as “Lyniel” — as being 15 years old, which would make his birth year 1915 or even 1914, depending upon exactly when the census was taken. Hooker was one of nine sons and three daughters of James and Sallie Hooker. The family lived on a farm just outside Sanford. James ran the farm, with all the children working to make ends meet. Sallie kept everyone fed and clothed. Little is known about Hooker’s early life.

Sanford, in North Carolina’s Piedmont country about 40 miles southwest of Raleigh, was the birthplace of three major-league baseball players. Bill Harrington pitched three years with the Philadelphia A’s, and Albie Hood played one season at second base with the Boston Braves. Dick Such pitched one season with the Washington Senators and spent 25 years in the big leagues as a pitching coach.

The first newspaper account in which Hooker is found noted him playing baseball for Captain Cole’s Giants in North Carolina’s prison league in 1936. He pitched a 12-inning complete game, giving up six hits and beating the Print Shop Devils, 3-2, for the Giants’ sixth consecutive victory.1 Hooker’s team represented Central Prison, a state prison in Raleigh. Why Hooker was serving time is unknown. By 1939 Hooker was out of prison, living in a rented room in Raleigh, and working as a dishwasher at the Sir Walter Hotel.

Hooker’s pitching gained notice and in 1940 he was signed by the Eagles. Right around the beginning of the season — on April 27, 1940 — Hooker’s father died in Sanford at the age of 75.2 Hooker started 11 games for the Eagles; he pitched two complete games and finished the year with a 3-5 record.3 The Eagles battled for the pennant that year, but ended up in third place in the Negro National League finishing with a 26-21-1 record.

Before the 1941 season began, Hooker staged a holdout. In his biography of Eagles co-owner Effa Manley, Bob Luke relates that Hooker returned his contract unsigned, noting, “terms not acceptable.” In turn, Manley fired off a missive stating that she was “quite surprised.” She felt that there had been outside influence on him in returning the contract, adding, “I cannot believe it was your idea. I cannot even understand you permitting it to be done.” According to Luke, “Effa told Hooker that anyone familiar with his record last year would certainly feel ‘you had been treated more than fairly. I expect you to sign the enclosed contract, return it, and be ready to meet the bus in Raleigh about mid-night April 3.’”4 Hooker was waiting suitcase in hand, and rejoined the Eagles’ rotation, which included Jimmy Hill and Max Manning. He pitched in 13 games, starting seven of them, and finished the season with a record of 4-2 and a 3.64 ERA as Newark once again finished third in the NNL with a 27-23-1 ledger.

Hooker’s 1942 season was one of his best in terms of his won-lost record. He pitched in 17 NNL games, starting 10 of them, and finished 6-1 with a 4.42 ERA. The team finished in third place again. After the season Hooker returned to Raleigh and on December 30 he married Bettie E. Jones, who was listed as being three years his senior, which indicated a birth year of 1919 for Hooker; in truth, Bettie actually may have been a year or two younger than her husband.

The war years continued to be lean ones for the Eagles. In 1943 the squad finished in fourth place with a 26-32 record. Notably, Hooker and Jimmy Hill delivered a one-two knockout punch in a doubleheader against the New York Black Yankees at Ruppert Stadium in Newark on June 10. In the opener, Hooker hurled a seven-hit, 4-0 shutout in which he “rose to great heights in the 8th inning when he struck out three straight batters with the bases loaded to prevent a score.”5 Hill was even better; he “turned in a brilliant no hit no run game in the seven-inning nightcap.”6 Hooker led the Eagles in pitching victories, posting a 6-4 record with a 3.79 ERA in league play. He also made a two-inning start for the North All-Stars that season.

Things did not improve much for the Eagles in 1944 as they dropped to fifth place with a 27-35 record in NNL play (32-35 overall). Hooker again led all Newark pitchers in wins with only five, and he finished with a losing mark of 5-6 to go with his 4.41 ERA.

In 1945 Newark improved slightly to a 25-24 record and a third-place finish in the NNL, but Hooker fell to 2-5 in spite of a vastly improved 2.62 ERA. He started the season in a more exotic locale than Newark: on May 26, the Wilmington (Delaware) Morning News reported that “[Ray] Danbridge [sic] and Len Hooker have succumbed to the ‘south of the border’ offers.”7 Hooker’s stay with the Veracruz team in Mexico was brief, and he did not pitch effectively there, going 2-5 with 16 strikeouts and a 6.54 ERA in 52⅓ innings pitched in 12 games.8 By July, Hooker was back with Newark as is evidenced by an article that said, “Newark will count on Len Hooker” in a game against the Black Yankees at Victory Field in Indianapolis.9

After the 1945 season Hooker joined Biz Mackey’s Negro All-Stars as they played a five-game series against Brooklyn Dodgers coach Chuck Dressen’s All-Stars. Hooker started two games and was the losing pitcher in both, although he pitched adequately. In 13 innings he allowed 11 hits and six runs (two of them unearned) for a 2.77 ERA.10 Mackey’s All-Stars ended up with a 0-4-1 record, and Hooker’s performance was not enough for the Brooklyn Dodgers to become interested in him. (The Dodgers’ Branch Rickey eventually did sign three of Mackey’s All-Stars, Johnny Wright, Don Newcombe, and Roy Campanella.)

In January 1946 Hooker joined Joe Lillard, a football star, as he led an all-Negro baseball team on a Pacific tour as part of the USO Camp Shows. Players from the Black Yankees, New York Cubans, and some Puerto Rican players also took part. Over three months they played 30 games against service teams in the Central and Southwest Pacific.11

Hooker returned from the USO tour in time to join the Eagles for the 1946 season. The Eagles also welcomed back numerous players who had been away during World War II, including Leon Day, Larry Doby, Monte Irvin, Oscar Givens, Clarence “Pint” Isreal, Charles Parks, and Leon Ruffin. The infusion of talent led the Eagles to soar to their greatest heights as they finished 50-20-2 for the season and won both the first- and second-half NNL pennants. Day, Manning, and Rufus Lewis were all aces that year, and Hooker was relegated to a lesser role than he had played for the team during the war years. Hooker posted a 4-4 mark with a 3.62 ERA in league play; he finished at 5-5 with a 3.86 ERA against all competition that season.

Though his role had diminished somewhat, Hooker was far from an afterthought and he ended up seeing action against the Kansas City Monarchs in the 1946 Negro League World Series. He started Game Three against the Monarchs’ Jim LaMarque at Kansas City’s Blues Stadium on September 23. He had a rough time, surrendering six runs in four innings before reliever Cotton Williams entered the game in the fifth. Hooker was tagged with the loss as the Eagles suffered a humiliating 15-5 defeat. Hooker found redemption in Game Six, on September 27 at Newark’s Ruppert Stadium. After the Monarchs knocked Leon Day’s pitches around the park for five runs in the first inning, Hooker took over in the top of the second inning and went the rest of the way, earning the win as the Eagles evened the Series with a 9-7 triumph.12 Hooker received fielding help from Day, who had moved from the mound to center field. Monte Irvin recalled that “Buck O’Neil hit a deep line drive to right center field and Leon made a great over-the-shoulder catch to save the game.”13

After the World Series, Hooker pitched for the Havana Reds during the 1946-47 Cuban League winter season. He was 0-1 in three games, and the Reds lost a one-game playoff to Matanzas for the league championship.14

The 1947 season found Hooker back in Newark. On May 30 the Eagles took part in a Negro League showcase doubleheader that also featured the Homestead Grays. Branch Rickey was to attend both games as he had an interest in watching both Monte Irvin and Larry Doby play.15 Hooker was not used in either game of the doubleheader, and missed out on another opportunity to try to impress the Dodgers’ general manager. Newark (50-38-1) finished in second place behind the New York Cubans. Hooker’s performance dropped off dramatically. In 14 games — 10 starts — he managed only a 2-6 record and he had a 4.18 ERA.

Hooker finished 1948 with a 6-5 record and a 3.06 ERA. The Eagles, having lost many of their future Hall of Famers, fell to third place in the NNL with a final ledger of 29-28-1 in league play (33-31-3 overall). Hooker pitched in 14 NNL games, starting 11 in what ended up being his final season with the Eagles.

In February 1949 Hooker returned to Havana to play ball. This time, rather than playing in the Cuban winter league, he was a member of Panama’s Spur Cola team in the Caribbean Series. He pitched in only two games (9⅓ innings, 0-0) as Panama placed third in the series.16 Returning to the United States, Hooker barnstormed with the Brooklyn Cuban Giants before he made his way to Organized Baseball, pitching for the Farnham Pirates and then the Drummondville Cubs of the Class-C Quebec Provincial League; no statistics are available from this season.17

In the spring of 1950 Hooker joined the semipro St. Joseph (Michigan) Auscos for a brief barnstorming stint.18 Then he returned to Drummondville for the 1950 and 1951 seasons. During his first full year with the Cubs he posted a record of 11-6 with a 2.53 ERA. He followed that up in 1951 with a 10-9 mark and a 3.79 ERA, after which his professional baseball career came to an end.19

By 1965 Hooker owned a tavern in Newark, New Jersey, that he named Hooker’s Elbow Room. His application for a liquor license listed himself as the president of the corporation and his wife, Bettie, as secretary-treasurer.20 Hooker apparently made a good living from the tavern. By August 10, 1976, when the officers of the United Licensees Beverage Association of Newark were installed at an association dinner, Hooker was listed as one of the organization’s trustees.21

Hooker died in Newark on December 18, 1977. He was survived by his wife; two sisters, Anna Glover and Nordelle Hooker; and a brother, Melvin Hooker. Leniel and Bettie had no children. The funeral service was held at the New Hope Baptist Church in Newark and burial was at the Glendale Cemetery in Bloomfield, New Jersey.22

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted the following:

Ancestry.com.

Baseball-Reference.com.

Riley, James A. The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues (New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers, Inc., 1994).

Seamheads.com was used for Negro League statistics and team records. (It should be noted that statistical variances can be found in different sources, which is quite common for most Negro League players).

Notes

1 “Prison Teams Battle in Overtime Contest,” Raleigh News & Observer, August 20, 1936: 9.

2 Raleigh News & Observer, October 14, 1940: 13.

3 Baseball-Reference.com has Hooker’s statistics at 3-4 starting 10 games with two complete games.

4 Bob Luke, The Most Famous Woman in Baseball: Effa Manley and the Negro Leagues (Dulles, Virginia: Potomac Books, 2011), 70.

5 “Newark Pitchers Blank New York Black Yanks Twice in Twin Bill,” Pittsburgh Courier, June 12, 1943: 19.

6 Ibid.

7 “Newark Eagles Boast Fine Squad of Baseball Stars,” Wilmington (Delaware) Morning News, May 26, 1945: 12.

8 Pedro Treto Cisneros, The Mexican League: Comprehensive Player Statistics, 1937-2001 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2002), 473.

9 “Negro National League Clubs Will Vie Tonight,” Indianapolis Star, July 26, 1945: 12.

10 “1945 Negro All Stars,” seamheads.com/NegroLgs/team.php?yearID=1945&teamID=NST&LGOrd=2&tab=pit, accessed February 2, 2019.

11 “Negro Baseball Stars to Make Pacific Tour,” Baltimore Sun, January 26, 1946: 11.

12 The brief summaries of the World Series presented here were culled from Richard Puerzer’s comprehensive account of the series that appears in the present volume and from Kyle McNary, Black Baseball: A History of African-Americans & the National Game (New York: Sterling Publishing Company, Inc., 2003), 120-24.

13 Monte Irvin with James A. Riley, Nice Guys Finish First: The Autobiography of Monte Irvin (New York: Carroll & Graf, 1996), 106.

14 Jorge Figueredo, Cuban Baseball: A Statistical History, 1878-1961 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2003), 283-85.

15 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, May 29, 1947: 16.

16 Figueredo, 313-14, 317.

17 Barry Swanton and Jay-Dell Mah, Black Baseball Players in Canada: A Biographical Dictionary, 1881-1960 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2009), 85.

18 St. Joseph (Michigan) Herald Palladium, May 20, 1950: 7.

19 Swanton and Mah, 85.

20 “Announcements: Notice of Application,” Newark Star Ledger, July 23, 1965: 34.

21 ‘Officers Named by Tavern Owners,” Newark Star Ledger, August 10, 1976: 28.

22 Newark Star Ledger, December 20, 1977: 72.

Full Name

Leniel Charlie Hooker

Born

June 28, 1916 at Sanford, NC (US)

Died

December 18, 1977 at Newark, NJ (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.