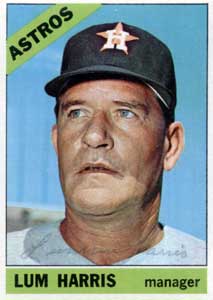

Lum Harris

Luman Harris said, “I wish baseball went on 12 months a year.”1 He spent 35 years in the game as a pitcher, coach, and manager, and enjoyed most of it, despite more losing seasons than winners.

Luman Harris said, “I wish baseball went on 12 months a year.”1 He spent 35 years in the game as a pitcher, coach, and manager, and enjoyed most of it, despite more losing seasons than winners.

Chalmer Luman Harris was born in New Castle, Alabama, on January 17, 1915, the third of six children of Chalmer and Lula Jane Harris. The family lived on a farm near Birmingham. His name was often shortened to “Lum” during his baseball career, but his friends called him Luman, pronounced “LOO-man.”

The 22-year-old Harris was pitching in semipro ball while working at a cotton mill in Buck Creek, Alabama, when an Atlanta Crackers scout offered him a contract with the Southern Association club in 1937. He traded shifts with a fellow worker, took a train to Atlanta to sign, and returned home in time for the night shift. After starting in Class B ball with Charlotte, he was called up to Atlanta in midseason.

Atlanta was the powerhouse of the Class A-1 league, equivalent to Double-A today. The Crackers had won two straight pennants, but fell to third in 1937. The right-handed Harris pitched primarily in relief, compiling a 1-1 record and a 3.00 earned-run average in 16 games. He also met the man who would shape his career. The Crackers’ catcher was Paul Richards, a 28-year-old Texan who had failed in big-league trials with the New York Giants and Philadelphia Athletics. The two forged a close friendship.

With Richards installed as manager in 1938, Atlanta took over first place in June and stayed there. The club sailed through the postseason playoffs and beat the Texas League champion, Beaumont, in the Dixie Series. Harris, starting and relieving, contributed ten victories and a 3.28 ERA, but did not pitch in the Dixie Series. After several of the pennant winner’s front-line pitchers were sold to the majors, Harris became a mainstay of the staff in the next two seasons, compiling a 32-17 record with a 3.70 ERA.

That earned Harris a promotion to the majors, but just barely. The Philadelphia Athletics acquired him before the 1941 season. The Athletics had sunk to the bottom of the standings after owner-manager Connie Mack sold his stars during the Depression. The club had endured seven straight losing seasons, finishing last four times. Mack was 77 years old and had been managing the A’s since they joined the American League in 1901.

Harris was happy to be there. “I’m one of the many ballplayers who is proud to say that I pitched for a fellow like Mr. Mack, the Grand Old Man of baseball, and I enjoyed every minute,” he said years later.2 When he joined the team in spring training, Mack told him, “Son, pitch up here like you did in Atlanta. That’s all it takes.”3 Unfortunately, the Athletics probably could not have beaten the Crackers. “We wasn’t in the thick of nothing but last place,” Harris recalled.4 The club finished last for his first three seasons in Philadelphia.

Harris was not the ace, but he wasn’t the worst pitcher on the staff, either. His stuff was a little short of big-league quality. He threw a fastball, a changeup he had learned from Paul Richards, and a knuckleball. He sometimes twisted his wrist when throwing the knuckler, producing a knuckle curve. During the three years in the cellar his record was 22-40 with an ERA over 4.00. He and the club hit bottom in 1943, when Harris was charged with 21 of Philadelphia’s 105 defeats. He had his moments: a four-hit shutout of Cleveland followed by a three-hit, one-run victory over Detroit in July. Sportswriters described him as unlucky, but he was often ineffective. He gave up five or more runs in 12 of his 27 starts, including a painful stretch when he surrendered 31in 47 innings.

With most major leaguers in military service during World War II, teams made do with youngsters and veterans too old or infirm for the draft. Spring training in Florida was banned; the A’s trained in Frederick, Maryland, often in the snow. Harris put it in perspective: “It was tough, but I’ll say this: I think anything was better than the war.”5

In 1944 the Athletics climbed over most of the weakened competition into third place in late May. During the month Harris spun a two-hit shutout against the Browns and a three-hit victory over Detroit. He was having his best year, with a 3.30 ERA, an AL-best 1.3 walks per nine innings, and a 10-9 record, his only season above .500. But in August the military draft caught up with Harris. Teammates filled a bag with dollar bills as a going-away present and Mack paid him his full year’s salary.

He spent the next 17 months in the Navy, where his primary duty was playing ball. He joined a Navy all-star team that entertained sailors and troops in Hawaii. The players slept on board a barge; Harris had a lower bunk below Ted Williams. He remembered that Lieutenant Williams refused to move to officers’ quarters because he wanted to stay with his teammates.

The Navy staged a Little World Series in Honolulu in 1945 pitting American League against National League players. Harris won two games over the NL squad that included Stan Musial, Billy Herman, and other big leaguers. He wrote to Mack to recommend one of his teammates, a minor-league first baseman. The Athletics drafted Ferris Fain from the Pacific Coast League and he won two batting titles.

Harris came home in 1946 to find Philadelphia back in last place. Mack was counting on him to pick up where he had left off and gave him a raise over his 1944 salary, but Harris’s arm was sore. The A’s lost 105 games; he was charged with 14 of the defeats against three victories, with a 5.24 ERA. The Washington Senators claimed Harris on waivers during the winter, but released him in May 1947.

For four years Harris bounced around Triple-A from the Red Sox to the Giants to the Tigers to the Indians farm systems. In 1948 he rejoined Paul Richards, who was managing Triple-A Buffalo, and pitched in relief (not very well) for the Bisons’ 1949 International League pennant winners. He wound up his playing career with the International League Baltimore Orioles in 1950.

Returning home to Alabama, Harris worked as a carpenter with his brother Tom. On a hot day they were putting a roof on a house when Luman got word that the Chicago White Sox general manager, Frank Lane, had called. Lane had hired Richards to manage the White Sox in 1951 and Richards wanted Harris as batting-practice pitcher. Harris was back in the big leagues. He and Richards would stay together for 21 years.

Richards surrounded himself with cronies. One coach, Jimmy Adair, was a childhood friend; another, Doc Cramer, had played with him on the Athletics and Tigers. Harris soon became the manager’s third-base coach and consigliere (adviser). Richards said, “Luman reads me like a book.” Harris played the good cop to Richards’ bad cop. Richards held himself aloof from his players, seldom speaking to them and even more rarely patting them on the back. Harris listened to their gripes, repaired the wounded egos Richards left in his wake, and played the court jester, “relaxed, laughing and cutting up.”6

After four seasons in Chicago, where he revived a perennially losing franchise, Richards moved on to the Baltimore Orioles, an even more hopeless building job as a recent replacement for the St. Louis Browns. Harris went with him. They were so closely allied that the Orioles players called Richards “Number 12,” his uniform number, and Harris “Twelve-and-a-half.” Richards sent his alter ego to the mound to change pitchers, so the man being relieved couldn’t put up an argument.

Harris became an offseason ambassador for the team, speaking at civic-club luncheons and sports banquets in Maryland and Pennsylvania. He had turned into a polished raconteur, telling stories and showing off his country wit. Baltimore News-Post writer John Steadman called him “a beast of burden for the Orioles in training camp and pre-game workouts.”7 Harris pitched batting practice and hit fungoes to infielders. He claimed he could hit curves and screwballs with the skinny fungo stick and proved it by “pitching” batting practice with the bat.

It took five years, but by 1960 the Orioles had built a young team known as the Baby Birds and they hung in the pennant race until September. They finished second to the New York Yankees and were in third place at the end of August 1961 when Richards left to become general manager of the expansion Houston Colt .45s, the first major-league team in his home state. Harris replaced him as interim manager of the Orioles.

Harris faced his first big test when the Yankees came to town on September 19. Roger Maris had hit 58 home runs; Baltimore was Babe Ruth’s hometown and fans wrote to Harris advising him how to keep Maris from breaking the Babe’s record of 60. Maris went hitless in the first game. The second game was the Yankees’ 154th of the season. By decree of Commissioner Ford Frick, it was Maris’s last chance to pass Ruth or else he would be recognized only as the 162-game record holder. Baltimore’s starter, the veteran junkman Skinny Brown, asked Harris whether he should pitch around Maris. “No, let’s get him out,” the manager told him. Maris managed one single in four tries against Brown, then Harris brought in knuckleballer Hoyt Wilhelm to pitch to the beleaguered slugger in the ninth. Maris topped Wilhelm’s knuckler for a weak dribbler back to the mound. After the game a reporter asked Harris why he hadn’t walked Maris and pitched to Yogi Berra. “I said I’d been a manager only two weeks and I wasn’t smart enough to walk Maris to get to Berra,” he replied.8

The next day, in game 155, Maris hit his 59th homer, off Milt Pappas. When the two teams met again at Yankee Stadium six days later, Maris tagged Baltimore’s Jack Fisher for number 60. He hit his 61st on the season’s final day, off Boston’s Tracy Stallard.

Baltimore went 17-10 under Harris in September and held onto third place. Harris told sportswriters he would like to stay on as manager if the club would give him a two-year contract. The Orioles didn’t offer, perhaps wanting to make a clean break with Richards.

That didn’t worry Harris; a coaching job was waiting for him in Houston, where Richards was loading the staff with his pals, under manager Harry Craft. The expansion team was predictably bad, losing 96 games in each of its first three years. Meanwhile, Richards was stockpiling young talent, as he had in Baltimore. Joe Morgan, Rusty Staub, and Jimmy Wynn debuted in 1963. When the Colts didn’t improve in 1964, Craft was fired in September and Harris became manager.

At 49, he had spent 20 of his 28 years in baseball as a player or coach under Richards. His only managing experience, aside from 27 games as the interim leader of the Orioles, had been in the Venezuelan and Puerto Rican winter leagues. “I learned practically all I know about managing from Mr. Mack and Paul Richards,” he said. “But there isn’t anybody who can manage like somebody else. Sure, I’ll make use of a lot of their ideas and methods, but I’ve got some thoughts of my own. So I’ll manage like Luman Harris.”9 After Houston lost to the Dodgers in the next-to-last game, Harris locked the clubhouse doors and told the players what he expected of them next year.

In 1965 the club had a new home, the Astrodome, and a new name, the Astros. The world’s first indoor stadium proved less than ideal for baseball—the grass died and fielders sometimes lost sight of fly balls against the roof. Batted balls didn’t carry well in the air-conditioning; the Astrodome was one of the worst hitters’ parks in the majors. That helped Houston’s pitchers allow the second fewest runs in the league, but the offense scored the second fewest. After the Astros finished ninth with 97 losses, a sportswriter asked Harris to assess the season. He replied, “I’d rather not.”10

The franchise got a new majority owner in 1965 when Judge Roy Hofheinz bought out oilman Bob Smith. Hofheinz and Richards had been at odds almost from the beginning; Richards wanted total authority, and so did Hofheinz—and the Judge signed the checks. After the season Hofheinz fired the general manager and one of his underlings fired Harris by telephone.

Out of baseball for the first time since 1937, Harris returned to his Alabama farm with his wife, Margaret, their two sons and their daughter. He didn’t have to look far for a new job. In August 1966 Richards became the Atlanta Braves’ vice president for player personnel, with the authority of general manager, and began reassembling his team of cronies. The next season Harris took over as manager of Atlanta’s Triple-A farm club in Richmond, Virginia.

A seventh-place finish in 1967 cost Atlanta manager Billy Hitchcock his job. Richards wanted Harris to replace him, but the team’s chairman, Bill Bartholomay, resisted reuniting the sidekicks. Bartholomay went along only after exacting a promise from Richards: If Harris didn’t work out, Richards would take the job himself. When Harris was introduced to the press in St. Louis during the World Series, he professed his loyalty to Richards: “First he made me a big-league pitcher, then he made me a big-league coach, and then he made me a big-league manager, so why shouldn’t I admire the man?”11 Sportswriters speculated that Harris was nothing but Richards’ puppet.

Atlanta had talent with Henry Aaron, Rico Carty, Joe Torre, and Felipe Alou in the lineup and Phil Niekro heading the pitching staff. But some of the talent loved a good time off the field. A sportswriter called the team “the playboys of Peachtree” Street. The Braves were tied for second place behind the Cardinals on July 4, 1968, before illness and injuries brought them down. Carty had contracted tuberculosis and missed the whole season. A beaning sent Torre to the disabled list for a month. Third baseman Clete Boyer was lost for nearly half the season after a Don Drysdale pitch broke his hand. Atlanta rose to fifth place but the team’s 81-81 record was only four wins better than the year before.

The 1969 season upended the historic structure of major-league baseball. Both leagues expanded to 12 teams and split into two divisions. There would be no more pennant races, only a “race for half a pennant,” as the sportswriter Red Smith put it.12 The realignment put Atlanta in the National League’s Western Division with Los Angeles, San Francisco, San Diego, Houston, and Cincinnati. The geographical atrocity came about so that the St. Louis Cardinals and Chicago Cubs could be in the same division to maintain their historic rivalry.

During spring training the Braves traded Joe Torre to the Cardinals for Orlando Cepeda, a former National League Most Valuable Player. Torre, serving as the Braves’ player representative in the newly assertive Players Association, had clashed with Richards, one of the most belligerent anti-union voices in baseball’s front offices. Richards traded his powerful 28-year-old catcher for a first baseman who was three years older and had a history of knee problems. Cepeda turned in a mediocre performance and Carty missed much of the season with a separated shoulder, but Atlanta hung in a tight race.

In September five of the six Western Division teams were separated in the standings by just two games. Then the Braves reeled off a ten-game winning streak. Carty returned to the lineup and 47-year-old Hoyt Wilhelm joined the pitching staff. Carty rang up a 1.031 on-base plus slugging percentage (OPS) and knocked in 25 runs in the final month, while Wilhelm saved four games and won two. The Braves clinched the division title on the next-to-last day, igniting a raucous celebration in Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium. Jubilant fans charged onto the field and mobbed the players. Harris lost his watch and glasses in the melee. But it was only half a pennant. The “Miracle Mets” were waiting.

The Mets had won 100 games, seven more than the Braves, and were the clear favorites in baseball’s first playoffs (officially, not playoffs but the League Championship Series). They had Tom Seaver, Jerry Koosman, and Tug McGraw on the mound, backed by the league’s youngest lineup. The Braves could not use Wilhelm in the postseason because he had joined the team after September 1. Felipe Alou was hurt and could only pinch-hit. Henry Aaron questioned his teammates’ attitude; he thought some of them were “satisfied we made it this far.”13 Despite Aaron’s three home runs, the Mets swept the series in three games.

The 1969 season was the highlight of Harris’s major-league career, the only time he finished in first place as a player, coach, or manager. But he got little credit for the club’s success. The Braves had finished fifth in the league in both runs scored and runs allowed; they won their half-pennant by getting hot in September, with a 20-5 record. The next year they fell to fifth in the six-team division.

Third baseman Clete Boyer was one of several Braves forced to take pay cuts after the disappointing finish. Early in the 1971 season he vented his anger to a sportswriter and challenged the Richards-Harris partnership. Boyer said he would “go anywhere to get away from Paul Richards” and dismissed Harris as a manager in name only.14 “You know why we lose on the road?” he said. “There’s no telephone direct to the dugout like there is in Atlanta, so Richards can tell Luman Harris what to do.”15 The outburst led to Boyer’s release and turmoil in the clubhouse, because Boyer was popular with his teammates. The Braves improved their record to 82-80 and finished third, saving Harris’s job. But he received only a one-year contract extension.

Before the 1972 season Harris said, “This is the best personnel I have had in Atlanta.”16 He had broken in several promising young players, including Darrell Evans, Ralph Garr, and Earl Williams. But the early results were not good. At the end of May the club stood at 18-22, seven games out of the lead. Harris acknowledged speculation about his job security, but said he wasn’t concerned: “The way I look at it, there’s only one letter difference between hire and fire. I’ll tell you this. I don’t know what I or anyone else could do differently. When people who have proved they are good pitchers lose their stuff, when people make mistakes out on the field, or when fellows you know can hit don’t, there isn’t much anyone can do but sit on the bench and squirm.”17 Richards took the blame for failing to improve the team. “Fire me, not him,” he told the writers.18

The Braves’ chairman, Bill Bartholomay, did just that. In June he reassigned Richards as a scout and promoted farm director Eddie Robinson to director of player personnel. Robinson was another longtime Richards sidekick and a friend of Harris’s. The three men had played golf and hung out together since the Baltimore days. Now Richards warned Robinson, “You’re gonna get to fire Luman.”19 By August Atlanta was 16 games out of first place and Richards’ prediction came true. Fan favorite Eddie Mathews became the new manager.

The bitter ending in Atlanta broke up the friendships. Harris never spoke to Richards or Robinson again, even though Robinson called and wrote to him. Richards and Robinson were estranged for several years, but eventually reconciled. Harris never worked in baseball again, either. Atlanta Constitution writer Wayne Minshew recalled, “The last thing Luman said to me was, ‘I’m going to my farm in Birmingham and I’m never leaving.’ And he was true to his word right up until the day he died.”20

Late in life Harris contracted diabetes and had a leg amputated. He died at 81 on November 11, 1996, in Pell City, Alabama.

Notes

1 The Sporting News, April 11, 1964, 12.

2 Luman Harris, undated interview by Kit Crissey, SABR Oral History Committee.

3 The Sporting News, April 11, 1964, 12.

4 Harris interview.

5 Harris interview.

6 The Sporting News, March 10, 1960, 9.

7 The Sporting News, September 20, 1961, 6.

8 The Sporting News, April 11, 1964, 12.

9 The Sporting News, October 3, 1964, 7.

10 The Sporting News, November 20, 1965, 17.

11 Jesse Outlar, “The Reunion of Richards and Harris,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution Magazine, April 7, 1968, 27.

12 Red Smith, Strawberries in the Wintertime (New York: Quadrangle, 1974), 63.

13 Hank Aaron with Lonnie Wheeler, I Had a Hammer: The Hank Aaron Story (New York: HarperCollins, 1991), 202.

14 United Press International, in Bucks County (Pennsylvania) Times, May 29, 1971, 17.

15 Associated Press, in Lawton (Oklahoma) Constitution, May 28, 1971, 25.

16 “Any One of Five Can Do,” Sports Illustrated, April 10, 1972, online archive.

17 United Press International, in Middlesboro (Kentucky) Daily News, May 31, 1972, 12.

18 The Sporting News, June 10, 1972, 20.

19 Eddie Robinson interview, August 18, 2006, Fort Worth, Texas.

20 Calhoun (Georgia) Times and Gordon County News, December 23, 2000, 3.

Full Name

Chalmer Luman Harris

Born

January 17, 1915 at New Castle, AL (USA)

Died

November 11, 1996 at Pell City, AL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.