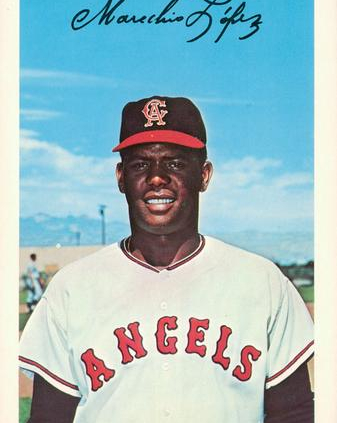

Marcelino Lopez

As of 2010 he had won more major-league games than all but one left-hander born in his native Cuba, but when considering that he had 14 victories by the end of August as a 21-year-old rookie, his 31-40 career mark could be seen as a disappointment. Though he did not establish himself further as a starter, he did play a valuable role as a reliever of the champion Baltimore Orioles of 1970.

As of 2010 he had won more major-league games than all but one left-hander born in his native Cuba, but when considering that he had 14 victories by the end of August as a 21-year-old rookie, his 31-40 career mark could be seen as a disappointment. Though he did not establish himself further as a starter, he did play a valuable role as a reliever of the champion Baltimore Orioles of 1970.

Marcelino Pons Lopez was born on September 23, 1943, in Havana, Cuba. “He told me he knew (Fidel) Castro and even played ball against him,” said Roy Firestone, the Orioles spring-training batboy as a child. “He told me Castro was a huge baseball fan, but a lousy player.”1 Lopez initially appeared to be on the fast track, signing with the Philadelphia Phillies in the fall of 1959 just 10 days after his 16th birthday, and leading the Florida State League with a 2.35 earned-run average a year later. Just 5-feet-11 and weighing 160 pounds at the time, he struck out 231 batters in 199 innings and earned a spot on the Phillies roster after the season.

Unwilling to rush Lopez, the Phillies sent the 17-year-old to the Williamsport Grays of the Eastern League (Single A), where he caught the eyes of the big-league brass again when the Phillies visited for an exhibition. Lopez went 10-5 before a blister ended his season after 22 starts. When he returned to action that winter in the Venezuelan League, Sports Illustrated reported that he “handled major-league hitters with ease.”2

Lopez and his fiancée, Zoraida, were married in January 1962, and he became the father of a son, Eduardo, in October; but most of the news concerning him that year was not good. His arrival two weeks late to spring training because of visa problems was just the beginning of his troubles. A tender elbow prevented Lopez from letting loose and, though he impressed anyway, more elbow soreness contributed to a disappointing performance at Triple-A Buffalo (3-7, 5.57 ERA) as his walk total soared to 95 in 126 innings.

Wildness continued to plague Lopez that winter in Venezuela, but he went 9-6 for La Guaira and hurled 10 complete games, including a 15-inning masterpiece in stifling heat to beat Caracas 2-1.

By 1963 a more mature (and on-time) Lopez showed up in spring training. Physically, he’d grown to 6-feet-3 and 195 pounds, and his ability to speak English had come a long way since his first pro season in Tampa. He had an opening to make the team after fellow southpaw Dennis Bennett fractured an ankle in an automobile accident in Puerto Rico in January, and Lopez seemed ready to take advantage of it. He was so impressive that a poll of National League writers named him Philadelphia’s Most Improved Pitcher, Best Young Pitcher, and Likeliest to Improve.

With his elbow problems behind him for the time being, Lopez made a believer out of Gene Mauch and opened the 1963 season in the big leagues. “Whenever I saw him before, he never threw hard. This spring, he’s been throwing bullets,” Mauch observed. “He’s got a good curve, and a change, too. He’s a natural athlete. He can hit, and he’s one of the fastest runners on our squad. He can field his position, too. Lopez has a lot of poise for a kid of 19.”3

Lopez’s major-league debut, against the St. Louis Cardinals at Busch Stadium on April 14, was hardly memorable. He started the game and was taken out in the first inning after walking the first two batters and giving up a double to Ken Boyer. He escaped being saddled with the loss when the Phillies scored five runs in the last four innings and won the game. He pitched briefly in relief on the 16th, then on the 20th he started against the Cardinals again, at Shibe Park, and pitched five innings to get his first major-league victory, 6-2. He pitched briefly on the 27th before suffering an elbow injury, and was sent to Triple-A Arkansas at the end of the month. Two months went by before Lopez was able to pitch, and he was generally ineffective in 69 innings, going 3-5 with a 5.74 ERA in 17 appearances (12 starts). It was a frustrating season, as evidenced by Lopez’s reaction to being yanked in the second inning of a start against Jacksonville in August. Rather than hand the baseball to manager Frank Lucchesi, Lopez fired it over the stands, earning a $27.50 fine. “$25 for the throw, and $2.50 for the ball,” explained Lucchesi.4

Lopez’s elbow woes continued to cause him control problems that winter for La Guaira, but he rebounded in 1964 to have a solid season for a bad Double-A Chattanooga team. Though he had a decent 3.77 ERA and struck out 115 in 136 innings, his won-lost record was an unimpressive 6-10. “I pitched well but have the bad record because we have a bad club,” Lopez explained. “Our best hitter only hit .270.”5

Hard luck followed Lopez to the Caguas Criollos in Puerto Rico that winter, where he lost a trio of duels to Los Angeles Angels left-hander George Brunet by scores of 1-0, 2-1, and 3-2. Brunet and Lopez would be teammates come springtime, though, because on October 24 he was traded to the Angels in a complicated deal in which the Phillies, who were in a late-season pennant race, in effect “rented” Angels first baseman Vic Power for the last three weeks of the season, then sent him back to the Angels after the season, throwing in Lopez as a dividend for the rental.

Lopez wrapped up a busy winter by heading to the Dominican Republic to pitch in that league’s playoffs, and reported to spring training with no hard feelings towards the Phillies. “I didn’t get mad at Philadelphia because they have two good southpaws (Bennett,Chris Short), and they need more right-handers because of the short fence in left,” he said. 6

For a young pitcher with only six innings of big-league experience, Lopez seemed keenly aware of what the deal could mean for him. The Angels needed help in both their rotation and bullpen, and Brunet and Bo Belinsky were the only left-handers on the roster. Besides, Lopez said, “I also hear that LA park [Dodger Stadium, where the Angels were then playing] is good for pitchers. If you get the ball over, you win.”7

Lopez drew raves from teammates and opponents alike during spring training, and pitching coach Marv Grissom said he had winning stuff if he could get it over the plate, but cautioned, “… Unless he develops a curve, he (can’t) stay in the big leagues. He was choking the ball as he threw the curve. I told him to move it out onto his fingers where he could manufacture greater spin.” Grissom called Lopez “a quick and willing student,” and said he worked on the grip after practice every day. 8

Lopez accepted the challenge and tightened up his self-described “lazy curve.” By the end of April, Grissom called him “a cinch to win 15 games.”9 By August 23 he was 14-10, and he took a no-hitter into the bottom of the seventh two weeks later at Chicago. But he wound up 14-13 after missing the last two weeks of the season with a pulled rib muscle. If he had been able to pitch more at home (where he was 10-3), or less against the Yankees (who won all five decisions against him), he would have made good on his pitching coach’s prediction. Nevertheless, he took home rookie pitcher-of-the-year honors from the The Sporting News, and finished second to Orioles outfielder Curt Blefary for overall freshman honors.

Lopez’s 2.93 ERA and winning record for a 75-87 team were impressive accomplishments for a 21-year-old, but he was even better when he returned to Venezuela to pitch for La Guaira in the winter. Things started out badly. Lopez’s wife was among a group of four players’ spouses forced to disrobe during a robbery while they were grocery shopping, and he lost his first two decisions. After that, though, Lopez reeled off 12 straight wins and hurled 51⅔ consecutive scoreless innings at one point. By the end of the winter campaign, he was 12-3 with a 1.57 ERA, five shutouts, and nearly 150 innings pitched.10

The heavy workload caught up with Lopez in 1966. After a complete-game victory in Chicago in his season debut, Lopez won just six of 20 decisions the rest of the way to finish 7-14 with his ERA increasing by a full run to 3.93. A pair of blisters on his pitching hand prevented him from gripping the ball tightly early in the season, but Lopez had no trouble pinpointing the source of his struggles. “I left my best stuff in Venezuela. I didn’t fool myself,” he said. “I picked up a million bad habits because I am tired. I don’t even know where the ball is going. I don’t stride properly, my arm dips down and I don’t get my breaking stuff over.”11 Hitters started laying off his hard slider, and his ERA away from Anaheim Stadium was a miserable 5.31. The Angels offered Lopez an offseason job in their ticket department if he’d stay away from pitching winter ball, and he agreed. “It will cost me $4,000 not to go to Venezuela,” Lopez said. “But I have the chance to make $30,000, even $40,000, pitching for the Angels.”12

In the spring of 1967 Angels manager Bill Rigney told reporters he was building his pitching staff around Lopez, but the southpaw lasted only nine innings in his first three starts before heading to the disabled list with tendinitis. “I went to a doctor, and he said the worst thing I can do is rest the arm. My muscles are tight, and just need to be stretched,” Lopez said. “He said maybe my arm just got used to pitching after six straight winters, and tightened up when I did nothing. He give me some exercises, and said to throw every other day.”13

Six weeks later, Lopez returned to the mound and failed to retire any of five Baltimore Orioles hitters he faced in relief, walking four of them. Nine days later, on June 15, he was dealt to Baltimore with another minor leaguer for utilityman Woody Held. Lopez returned from a second trip to the disabled list to make his Orioles debut on July 30, then went back on the DL again a week later after failing to get past three innings or display much zip on his fastball in a pair of starts. He was a little better when he returned in late September. The season was a lost cause for Lopez; he pitched just 26⅔ innings, going 1-2 with a 4.73 ERA.

In 1968 Lopez was given a cortisone shot and the Orioles sent him down to the Miami Marlins of the Single-A Florida State League so that he could pitch himself back into shape. After posting a 3.50 ERA in 11 starts, he moved up to Double-A Elmira (3-2, 5.33 in nine starts), where arm woes bothered him again. In September, he finally had a breakthrough of sorts after having his tonsils removed. “It was real bad. I lost 30 pounds in three days. When they took them out later, I saw the worst tonsil on the left side,” Lopez said.”Three weeks later, I threw for 20 minutes. My shoulder felt good. Maybe it was my tonsils.”14

Flashing improved velocity, even if it wasn’t up to his 1965 level, Lopez went 5-3 that winter, again pitching for La Guaira in the Venezuelan League. He was not selected in the October 1968 expansion draft to stock the new teams in Seattle and Kansas City. He acquitted himself well in 1969 spring training with the Orioles, but was the last man cut before Opening Day as Baltimore opted to go with right-hander Mike Adamson. A devastated Lopez couldn’t hold back the tears, but he went to minor-league camp with the right attitude.

“Instead of grumbling, he did more than he was expected to,” said Baltimore Executive Vice President Frank Cashen. “He helped the manager run the pitchers. He coached third base. He even collected bats. Do you know, he was the fastest player in our entire minor-league camp?”15

Lopez went to Triple-A Rochester and pitched well in five starts. After he fired a seven-inning no-hitter at Richmond on May 4, the Orioles brought him back to the majors. Four times in his first six appearances, he hurled at least three scoreless innings out of the bullpen, earning victories on two occasions. Though he tailed off after a strong start, Lopez went 5-3 with a 4.41 ERA in four starts and 23 relief appearances for a Baltimore team that won 109 regular-season games. The club’s leading winner was off-season acquisition Mike Cuellar, the only left-handed Cuban-born pitcher to win more major-league games than Lopez. “Marcelino knew Mike Cuellar really well,” recalled Roy Firestone. “They grew up together in Cuba and ended up as teammates with a couple of teams.” (SOURE) Lopez appeared in the 12th inning of the first American League Championship Series game ever played, retiring another outstanding Cuban player, Tony Oliva of the Minnesota Twins. Then he made way for Dick Hall, who got the victory when the Orioles defeated Minnesota in the bottom of the inning. Lopez didn’t pitch in the World Series as the Orioles were upended by the New York Mets.

Lopez shed 20 pounds over the winter and spent the entire 1970 season with an Orioles team that won another American League pennant en route to the second World Series victory in the franchise’s history. In three starts and 22 relief outings, he posted a 2.08 ERA and held left-handed hitters to a .136 average. He helped Baltimore preserve a one-run lead in the bottom of the seventh inning of World Series Game Two by getting Cincinnati’s Bobby Tolan to pop up with two runners aboard. After the Orioles won the Series in five games, Orioles play-by-play announcer Chuck Thompson interviewed them one after another in the joyous clubhouse. “I just want to say I haven’t seen my mother in 10 years, and she’s probably watching me on TV now,” Lopez told him. “I’d like to say hello, and I’m all right. This is the greatest moment of my life, and I hope next year we can do it again.”16

Bases on balls were a problematic in an otherwise strong 1970 campaign for Lopez, as he issued 37 free passes in 60⅔ innings, and they drove Orioles manager Earl Weaver crazy. “I used to sit next to Earl Weaver in the Miami Stadium dugout and he was brutal with Marcelino,” Roy Firestone remembered. “He would scream and humiliate Marcelino for his inability to throw strikes … and this was still during spring training!”17

Lopez arrived at spring training in 1971 with a chance to compete for a spot in the starting rotation, and his spot on the team appeared secure when Jim Hardin was placed on the disabled list and Dave Leonhard was sent to the minor-league camp. Two days before Opening Day, however, Lopez was dealt to the Milwaukee Brewers for right-hander Roric Harrison and a minor leaguer. “We’ve been after Lopez for a long time, and I don’t buy that stuff that the Orioles felt he had a sore arm,” said Milwaukee’s director of baseball operations, Frank Lane, a former Orioles superscout. “I know at least three or four other clubs that would like to have his sore arm.”18

The Brewers tried Lopez in the bullpen, then moved him into the rotation in late June, but his control problems worsened. He walked 60 in 67⅔ innings and finished 2-7 with a 4.66 ERA. Late in 1972 spring training the Brewers sold him to the Indians, and he wound up starting the opener for Cleveland’s Triple-A team, the Portland Beavers of the Pacific Coast League. He struggled to throw strikes and finished 8-13 at Portland. In two starts and two relief appearances for the Indians in September, he walked 10 batters in 8⅓ innings and had just one strikeout. The Indians released him after the season. His major-league career was over with a 31-40 record and 3.62 ERA in 653 innings.

Lopez struggled through an 0-6 Triple-A season in 1973 for Hawaii and Oklahoma City, and wound up with Veracruz in the Mexican League in 1974. He resurfaced with the Triple-A Charleston Charlies in August of that season, posting a 1.73 ERA in 26 innings for the Pittsburgh Pirates affiliate, but walked 17. His last chance came in 1976 with the Double-A Columbus (Georgia) Astros of the Southern League, but he lasted only four appearances after walking seven in three innings.

Lopez died on November 29, 2001, in Hialeah, Florida. “Sadly,” Roy Firestone reported, “Marcelino died penniless.”19

Notes

1 Roy Firestone, post at Orioles Dugout web site, http://forum.orioleshangout.com/forums/showthread.php?t=68124, August 4, 2008.

2 “Philadelphia Phillies,” Sports Illustrated, April 9, 1962.

3 Allen Lewis, “Teen-age Hill Flash Tabbed Phils’ Starter,” The Sporting News, April 13, 1963, 38.

4 “Trav Hurler Fined $27.50, Tossed Ball Over Stands,” The Sporting News, August 3, 1963, 33.

5 Ross Newhan, “Rig and Grissom Hand Starting Job To Ex-Phil Lopez,” The Sporting News, April 10, 1965, 15.

6 Newhan, “Rig and Grissom.”

7 Newhan, “Rig and Grissom.”

8 Ross Newhan, “Chance, Newman, May, Lopez – Angels Flashy Big Four,” The Sporting News, May 15, 1965, 22.

9 Newhan, “Chance, Newman, May, Lopez.”

10 Eduardo Moncada, “Lefty Lopez Earns Raves As Mr. Shutout of Latin Loop,” The Sporting News, January 22, 1966, 25.

11 Ross Newhan, “Tired Lopez To Pass Up Winter Ball,” The Sporting News, October 8, 1966, 39.

12 Newhan, “Tired Lopez.”

13 Doug Brown, “Orioles Testing Question Mark Men On Mound,” The Sporting News, October 7, 1967, 29.

14 Doug Brown, “Tearful Exit Scene…Then Sweet Success For Lopez,” The Sporting News, July 12, 1969, 11.

15 Brown, “Tearful Exit.”

16 Marcelino Lopez, interview with Chuck Thompson following final game of 1970 World Series, video available at mlb.com, October 15, 1970.

17 Firestone, post at Orioles Dugout web site.

18 Larry Whiteside, “Brewer Patience Pays Off In Lopez,” The Sporting News, April 24, 1971, 22.

19 Firestone, post at Orioles Dugout web site.

Full Name

Marcelino Pons Lopez

Born

September 23, 1943 at La Habana, La Habana (Cuba)

Died

November 29, 2001 at Hialeah, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.