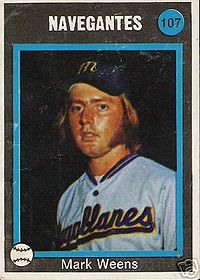

Mark Weems

“I watched him go. He never came back…It made me realize how fragile life really is.”[1]

Righty pitcher Mark “Dutch” Weems displayed promise as a Baltimore Orioles farmhand in the early 1970s. After turning pro in 1969, he reached Class AAA as early as 1971. He was playing winter ball in Venezuela after the 1973 season with an eye toward contending for a spot in the O’s bullpen in 1974.

Righty pitcher Mark “Dutch” Weems displayed promise as a Baltimore Orioles farmhand in the early 1970s. After turning pro in 1969, he reached Class AAA as early as 1971. He was playing winter ball in Venezuela after the 1973 season with an eye toward contending for a spot in the O’s bullpen in 1974.

Instead, fate took a hand on New Year’s Day 1974. Weems and three teammates with Navegantes del Magallanes were at Patanemo Bay, in the state of Carabobo. While playing in the water, Weems was swept out to sea and drowned. He was only 22 years old.

Mark Edward Weems was born on May 12, 1951, in Seattle, Washington, to Frank Calvert Weems III and Charlene Mae Weems (née Savage). Frank, a Navy veteran of World War II, was engaged in work related to the Hanford nuclear site in south central Washington. In the early 1950s, the Weems family – which also included Mark’s elder sister Laura – moved to the Los Angeles area. Frank embarked on a new career as an insurance claims adjuster. Charlene was an accountant, with an eye for spotting the smallest discrepancies. She wouldn’t rest until they were settled.[2]

The family lived in a few different L.A. suburbs, most notably La Puente. Mark played Little League, Pony League, Colt League, and Connie Mack ball.[3] A curious note is that he was naturally left-handed; pitching was one of the few exceptions.[4] His father was a coach – in 1964, Frank Weems led a team from La Puente to a berth in the Little League World Series. That was the year after Mark had stepped up to Pony League, but Frank stayed with the younger boys.[5]

Weems went to La Puente High School. As both a sophomore and a junior, the pitcher was named to the second team of the All-Southern California Interscholastic Federation (CIF).[6] He followed that up with first-team honors in 1969.[7]

In 1970, a year after he graduated, Weems said that his greatest thrill was to pitch and win the championship game in the nation’s largest high school baseball tournament.[8] That was the 34th edition of the tourney sponsored by the Pomona Elks Lodge.[9] As local writer Jim McConnell noted, “At its height, the tourney boasted a 48-team field, attracting most of the top high school baseball teams in Southern California.” In 1935, the event featured Jackie Robinson and Ted Williams. Eventually, over 150 future major leaguers played in it, including other Hall of Famers.[10]

Weems wasn’t just an athlete. As he recalled in 1973, “I enjoyed playing baseball in high school, yes, but my real pleasure was playing the drums. I was good at the drums.”[11] That musical pursuit was another thing he shared with his father.[12]

The Orioles made Weems their fifth-round pick in the amateur draft in June 1969 on the recommendation of scouts Al Kubski and Jim Foster. The news came as a surprise to Weems. Speaking in 1973, he said, “I knew that the draft was coming up, that was about all. I hadn’t taken myself or baseball seriously, hadn’t given a thought to anyone drafting me and I was shocked to hear that the Orioles drafted me.”[13]

For a short time in between getting drafted, graduating, and signing with the Orioles, the young man played for the San Bernardino team in the Southland collegiate circuit. On June 17, he struck out 17 against a visiting team from Bend, Oregon.[14]

The new pro’s first assignment was Aberdeen, South Dakota, in the Northern League. “I’d rather forget that one,” said Weems in 1971. “My earned run average was about nine. Couldn’t get the ball over.”[15] In 17 games (five starts), he was 0-3 with an 8.49 ERA. Although he struck out 35 in 35 innings, he also walked 24 and gave up 47 hits. In addition, the climate in Aberdeen was oppressively hot and humid. Weems told his family that after pitching, there wasn’t a dry spot on him.[16]

His 1973 memories continued, “I wasn’t thinking baseball yet, didn’t know whether I wanted to play baseball, and there the season was over and I had done terribly.”[17] Upon reflection, however, Weems took heart. “Over the winter I decided that the Orioles, a great club, must have thought I had the ability or they would not have drafted me, and that I owed it to the Orioles to make a good effort. I had a good high school record, and I decided to take the game seriously.”[18]

Indeed, things turned around for Weems in 1970 with Stockton in the Class-A California League. In 48 games, all in relief, he had a record of 5-4 with a 1.87 ERA. He struck out 113 batters in 82 innings pitched.

Weems explained how he became a reliever as a pro. “When I signed, I was barely 18, and I was only 5-foot-10 and 160 pounds. The scouts said, ‘If he’s going to be this small, how’s he going to pitch 250 innings in the big leagues? Two years after I signed, I had put on three inches and 30 or 40 pounds, but I was doing a pretty good job in short relief, so they kept me there.”[19]

At some point in the minors, Weems was dubbed “Dutch” for his longish blond hair. According to Dyar Miller, a fellow pitcher with Weems at various levels, “I believe one of his teammates thought (correctly) that he looked like the Dutch painter boy on Dutch Boy paint cans.”[20]

Bob Bailor, who was Weems’s roommate with Magallanes, called Weems “a beautiful guy. . . he loved life and was a super ballplayer.” [21] A March 1974 feature that was devoted to Weems also described his character. Author Al Cartwright called him, “A nice kid, but with a bit of the devil in him. . . ‘The kind of guy,’ an Oriole said, ‘that when the game was over, you knew there was no way he was going back to his room and read a magazine.’”[22]

To start the 1971 season, Weems moved up to Dallas-Fort Worth in the Dixie Association (Class AA). In 18 games for manager Cal Ripken Sr., he was 4-1 with an impressive 1.39 ERA. Thus, at the start of June he was called up to Baltimore’s top affiliate, the Rochester Red Wings.

“I haven’t seen him pitch,” said Red Wings manager Joe Altobelli. “But reports indicate that he can throw that fast one. It’s what you’d call a rising fastball. His problem at this level will be to keep it in the strike zone. Hitters in Triple-A ball are more selective and won’t go after the high one.” But Altobelli added, “He has really come along fast.” Weems himself said, “I’m excited about pitching. I know I’m very lucky to be this high in baseball when I just turned 20.”[23]

The initial trial at Triple-A did not go well. Weems posted a 6.88 ERA in 11 outings in roughly one month, going 0-1 in 17 innings. The organization then returned him to Dallas-Fort Worth, where he finished the season.

The big club gave Weems a look during spring training in 1972. Among other things, he relieved one of the team’s star pitchers, Jim Palmer, in an intra-squad game in mid-March.[24] He opened the season with Rochester but spent the bulk of it at Double-A again, this time with Asheville of the South Atlantic League. He led the circuit with 22 saves while going 4-2 with a 2.96 ERA. He struck out 74 men in 70 innings, but he also walked 43. “I was disappointed when they sent me down to Asheville,” said Weems in 1973. “I had done well, but they didn’t have any room on the Rochester staff for me that I could get enough work, and Asheville needed pitching.”[25]

Ahead of the 1973 season, Weems was in big-league camp with the Orioles again. Baltimore exec Frank Cashen remarked, “It is not inconceivable that Weems can make the jump from Double-A.”[26] Pitching coach George Bamberger, a noted developer of young talent, noted, “What I’ve seen of Mark, I like – definitely – and I want to see some more. He throws hard and has very good control for one so young.”[27] The latter remark conflicts with the numbers, though – over the course of his career, Weems walked 5.0 batters per 9 innings pitched.

Don Hood, who was Weems’ best friend and spring training roommate in 1973, offered another view: “Mark had a tendency to pitch wild, but just young wildness. Good fastball and slider. He had a pretty good curve to throw to lefthanders. We talked about pitching all the time. Two heads are better than one.”[28]

Al Cartwright described Weems and his approach to pitching. He called him, “A strong-armed, strong-willed kid . . .who had the daring you need to be a short reliever, to get the other side out in a jam. He would go in there and throw. Plain as that. Slam. Bang. Get ’em out. . . No tricky stuff.”[29]

Weems was back in Rochester in 1973, remaining with the Red Wings for the whole season and compiling a 9-7 record in 39 games. He had four saves and a 3.91 earned run average, striking out 57 – and walking 57 too – in 91 innings pitched. His main role was long relief. “It really puzzled me why I was used that way,” he said shortly after the season ended, “but I think Joe Altobelli had more confidence in Dave Johnson, and he was having a better year.”[30]

Weems was also a swingman in 1973, starting five games. On August 13, at Toledo, he pitched a one-hitter. (It was the nightcap of a doubleheader, so each game was seven innings.[31]) The only hit off Weems was a single by Jerry Manuel to lead off the third inning. It was a deft bunt that stopped between home plate, the mound and third base before any fielder could get to it.[32] After the game, Weems said that it took him by surprise – even though he’d seen Manuel lay down several perfect bunts in batting practice.[33]

Following the 1973 season, Weems was added to Baltimore’s 40-man roster (thus protecting him from the minor-league draft that December). That September, the Baltimore Sun had written, “Sometime in the near future, the Orioles are going to have to put Rochester farmhands Mark Weems and Dave Johnson in the parent club’s bullpen and tell them: ‘Okay, let’s see what you can do.’”[34]

As part of the development plan for Weems, Baltimore sent him to Venezuela. “The kind of year I have in Venezuela is the turning point on everything,” said Weems, also that September. “It’s a better league than the International, and it’s a good opportunity to show what I can do if I can get off to a good start.” That article noted how Enos Cabell had made the majors to stay that year after winning the batting crown in Venezuela in the 1972-73 season. [35]

Weems continued, “Even if I don’t get a chance with the Orioles, another team might want to make a trade for me. It’s not that I don’t want to play with Baltimore. It’s just hard to crack into the majors with them. Maybe I’d have a better chance with someone else.”[36]

The new manager of the Magallanes team was Jim Frey, a member of Earl Weaver’s coaching staff with Baltimore. The Magallanes front office was eager to get a playoff berth after missing for three winters in a row. Among the players who were coming from Organized Baseball to reinforce the team were right-handers Wayne Garland, Tom Dettore, and Don Hood; shortstop Bob Bailor; outfielders Bob Darwin, George Theodore, and Dave Augustine; and first baseman Mike Reinbach. However, two players stood out that season: outfielder Jim Rice, then a top prospect for the Boston Red Sox, and Weems.

The Orioles and Frey planned to refocus Weems on short relief (though he did wind up starting once for Magallanes). Before the winter season started, Weems had let his blond hair grow out close to his shoulders and begun sporting a beard.

Early in the season, Weems became a frequent image at the end of Navegantes games, especially at Valencia’s José Bernardo Pérez Stadium. His unorthodox style of pitching without a windup made many fans think that he wasn’t going to last long in the closer’s role. But on the field, Weems silenced those comments. He was developing finesse: he induced pop-ups and groundouts, and could even fool batters with off-speed deliveries. Soon Weems became Frey’s main reliever. He was called upon in the hardest situations during the eighth or ninth inning, and was quite successful.

With Magallanes, Weems was leading the league with 11 saves in 26 appearances (2-1, 3.29 ERA). He had struck out 34 men in 38 1/3 innings, though his control remained a concern, with 33 walks. Even though his season was cut short, as he sustained a leg injury and hadn’t pitched in a week before his fatal accident occurred,[37] Weems ended in a tie with the Cuban reliever Carlos Alfonzo for the league lead in saves. He might well have broken the circuit’s regular-season record at that time: 12, by Ed Sprague in the 1970-71 season.[38]

The league’s Christmas break was not long enough for Weems to go back to California to celebrate with his family, as he had done the previous year. Around New Year’s Day 1974 came another break in the schedule.[39] Three of the Navigators who were friends from the Baltimore system – Hood, Garland, and Bailor – went with Weems to the beach at Patanemo Bay near Puerto Cabello, about 94 miles west of Caracas. As Al Cartwright noted, the whole team had been warned about the dangers of this particular cove – “the waves were powerful and the undertow was dangerous. But they went anyway.”[40]

Hood told the Baltimore Sun that the four players went to Patanemo on December 31, enjoyed the water, and camped out overnight.[41] Pitcher Gregorio Machado, another teammate with Magallanes, surmised, “Maybe there were very few people at the beach and they didn’t get enough information about the sea. What I heard was that Weems got knocked down by the strong marine or submarine currents, properties of the sea at that place because it’s a real oceanic beach, there isn’t an island or reef or anything that neutralizes those currents and the consequent hard-breaking waves.”[42]

Cartwright went on to describe the subsequent events in more detail. “Weems, Hood, and Garland had been body-surfing in chest-high water. Hood and Garland came out to get a Coke. Weems said he’d join them in about 15 minutes. He wanted to ride a couple more waves. Bailor was on the beach reading.” Cartwright also noted that Bailor was a non-swimmer who went along for the company.[43]

Hood recalled that before he and Garland went to the concession stand, “He was only about 30 feet out and the water was waist deep. I can remember Mark standing there and waving his arms. He looked like a little kid out there. He wasn’t in any trouble at all.[44]

Cartwright’s account continued. “Bailor looked up and there was Weems obviously too far out, and struggling. Bailor yelled, and Hood ran and dove into the seas, but by this time the young pitcher had disappeared and Hood never saw him.”[45] Hood was also imperiled by his rescue attempt. “I was out there about 30 minutes and then a guy in a sailboat came along,” he said.[46]

“It had to be a frightening thing,” Jim Frey told Cartwright, “like being trapped in a giant washing machine. The water is that turbulent.” He added, “There is another theory that he [Weems] got a cramp, because he had been having a little nerve trouble in his back.”[47]

According to a 2014 account, Weems was an experienced swimmer and surfer.[48] However, the March 1974 story in the Sun said the opposite.[49] Weems’ sister Laura had no recollection that Mark had ever surfed, but she said that his natural athleticism carried over into swimming (though it was not a sport in which he had competed).[50]

When Frey heard the news from the son of a Venezuelan friend he’d been visiting, at first he laughed in disbelief. “But the boy insisted,” Frey told Cartwright, “and we turned on the radio just to go along with the gag. Right away we heard the news flash.” Frey and a Navegantes vice-president drove to Patanemo Bay, where a crowd of 500, drawn by the news, had gathered. “You must remember this is the big leagues in Venezuela,” Frey remarked, “and the ballplayers are important to them.”[51]

For three days, the friends of Weems – as well as the Venezuelan Navy and Coast Guard – searched for the body so the young man’s family could take it back home for burial. One of those friends was Ray Miller, a player-coach for Rochester in 1973 who was holding the same role with Magallanes.

In 1978, Miller – by then Baltimore’s pitching coach – stated that the death of Weems prompted him to quit playing and start teaching.[52] Miller told the story again in 1997, by which time he had been named Orioles manager. “On the fourth day, two of us found what was left of Weems’s body washed up in a cove. I’d been thinking during those days about everything in my life. I stayed alone with the body all that night until the authorities came back the next morning. I said to myself, ‘This isn’t a dream world you’re living in.’ Maybe I just grew up.”[53]

Weems was the third Magallanes ballplayer who’d died accidentally in less than five years. Pitcher Nestor “Látigo” Chávez perished in a plane crash at Maracaibo on March 16, 1969, while flying to the San Francisco Giants training camp. In a parallel to what happened with Weems, outfielder Herman Hill drowned at Guaicamacuto Beach on December 14, 1970.

Al Cartwright noted that the Magallanes club “arranged for Weems’ parents to fly in from California, and took care of embassy red tape to have the body shipped. The press played up the tragedy in True Detective fashion, with pictures of the body on the beach, in the morgue. The parents were given little privacy.”[54]

Cartwright also described how the death of Weems took “the spirit out of his ball club. The next three games were postponed. The last seven were played mechanically. The club had been a game out of first place, but lost five out of those seven.”[55] Magallanes finished in fifth place at 30-30. The team would not have qualified for the postseason, but as it developed, the playoffs were wiped out because the native Venezuelan players went on strike in a dispute over receipts from television.[56]

Later that month, a Red Wings fan named Richard Gorski wrote to Rochester’s Democrat and Chronicle to say that he got Weems’ cap at Silver Stadium at the end of the 1973 season and wanted to offer it to the family. Charlene Weems replied, “It’s a very lovely gesture. I’d like to keep it as a remembrance.”[57]

Weems had also made a special girlfriend in Rochester. Her name was Cheryl Miller. She worked for Eastman Kodak, the city’s biggest employer. The young woman had visited Venezuela during the season, and she made a trip to California as well to offer condolences to the family in person.[58]

Mark Weems was laid to rest in Rose Hills Memorial Park in Whittier, California. His father (who died in 1997, still haunted by the loss[59]) and mother (who died in 2009) were subsequently buried alongside him.

Don Hood’s mood was still somber when he reported to spring training in 1974. “It still bothers me a lot, especially at night,” he said. “Things just keep flashing in my mind. That’s why I couldn’t stay at the DuPont [Plaza Hotel in Miami, Orioles spring headquarters] again. I got an apartment instead.”[60]

One may only speculate what might have become of Weems had he not died. According to Earl Weaver, “Weems was a very good prospect. He probably would not have made the club this year [1974] because we have so many pitchers, but we were thinking about him as a future reliever.”[61] Pitching staffs were much leaner in those days. To start 1974, Baltimore carried just nine hurlers on its squad (as did five of the other 11 AL teams).

Had Weems been assigned to Rochester once more, depending on how he may have performed, he might have earned a callup in midseason or when the rosters expanded in September. As it turned out, however, the Orioles used just 11 pitchers over the course of the 1974 season.

Alternately – as Weems himself had speculated – he might have wound up with another club through a trade. Had the Orioles reversed field and dropped him from their 40-man roster, a change in scenery could have arisen from the Rule V draft. A couple of years down the road, the expansion draft might also have offered an opportunity.

Appropriately, Weems was commemorated on Opening Day 1974 at Silver Stadium during the pregame ceremonies with a moment of silence.[62]

Acknowledgments

This biography was originally published on February 6, 2021. It was updated on February 23 and 24, 2021. Special thanks to Laura Weems Hetzel, sister of Mark Weems, for her additional input (telephone calls with Rory Costello, February 16 and February 23, 2021).

The article was reviewed by Paul Proia and Jan Finkel and checked for accuracy by SABR’s fact-checking team.

Thanks also to Malcolm Allen and Paul Proia for additional research and to Dyar Miller for his input.

Sources

Books

Gutierrez, Daniel, Efraim Álvarez, and Daniel Gutierrez (son). La Enciclopedia del Beisbol en Venezuela. Liga Venezolana de Béisbol Profesional. Caracas (2006.

García, Giner; Bracho, Emil, and Sequera, Luis. 99 + 1. Fundación Magallanes de Carabobo (1996).

Tusa, Alfonso. Una Temporada Mágica. Liga Venezolana de Beisbol Profesional (2006).

Articles

Tusa, Alfonso. “Herman Hill in the Left Field of Guaicamacuto and Mark Weems on the Mound of Patanemo.” Unpublished article from 2018.

Internet resources

baseball-reference.com

pelotabinaria.com.ve (Venezuelan winter league stats)

findagrave.com

ancestry.com

Notes

[1] Earl McRae, “The Blue Jays’ First Choice,” Montreal Gazette, March 12, 1977. Republished as “Goodbye Connellsville” in the collection Requiem for Reggie, and Other Great Sports Stories. Toronto: Chimo Publishing, 1977.

[2] Laura Weems Hetzel, telephone call with Rory Costello, February 16, 2021 (hereafter Hetzel phone call #1).

[3] Mark Weems, “Publicity Questionnaire for William J. Weiss,” May 12, 1970.

[4] Laura Weems Hetzel, telephone call with Rory Costello, February 16, 2021 (hereafter Hetzel phone call #2).

[5] Hetzel phone call #1.

[6] “Area Baseballers Get CIF Honors,” Pasadena Independent, June 13, 1968: 29.

[7] Claude Anderson, “Chaffey’s DiCrasto Named to GIF Team,” San Bernardino Independent, June 25, 1969: 26.

[8] Weems, “Publicity Questionnaire.”

[9] “La Puente Wins Elks Tourney; No-Hitter for Edgewood’s Smith,” Pomona Bulletin, April 4, 1969:

[10] Jim McConnell, “Pomona tourney was historic,” InsideSoCal.com, March 3, 2009.

[11] Jim Elliot, “Mark Weems Wants Chance to Pitch,” Baltimore Sun, March 17, 1973: B1.

[12] Hetzel phone call #2.

[13] Elliot, “Mark Weems Wants Chance to Pitch.”

[14] “Collegiates Romp as Weems Fans 17,” San Bernardino County Sun, June 18, 1969: 40. Anderson, “Chaffey’s DiCrasto Named to GIF Team.”

[15] Craig Stolze, “Fastballer Hits Town,” Democrat and Chronicle (Rochester, New York), June 2, 1971: 45.

[16] Hetzel phone call #1.

[17] Elliot, “Mark Weems Wants Chance to Pitch.”

[18] Elliot, “Mark Weems Wants Chance to Pitch.”

[19] Larry Bump, “Winter’s Key to Future,” Democrat and Chronicle, September 19, 1973: 51

[20] Facebook post from Dyar Miller in response to question posed by Rory Costello about the nickname’s origins, January 8, 2021.

[21] McRae, “The Blue Jays’ First Choice.”

[22] Al Cartwright, “Unheeded Warning Led to Weems Tragedy,” The Sporting News, March 30, 1974: 54. Originally published in the Wilmington (Delaware) News-Journal.

[23] Stolze, “Fastballer Hits Town.”

[24] “[Tom] Shopay and [Johnny] Oates Excel in Oriole Squad Game,” Baltimore Sun, March 8, 1972: 23.

[25] Elliot, “Mark Weems Wants Chance to Pitch.”

[26] Lou Hatter, “No. 4 Starter to Keep Weaver Busy at Wheel,” The Sporting News, March 3, 1973: 25.

[27] Elliot, “Mark Weems Wants Chance to Pitch.”

[28] “Spring Training: One Who Didn’t Make It,” Cincinnati Enquirer, March 16, 1974: 29.

[29] Cartwright, “Unheeded Warning Led to Weems Tragedy.”

[30] Bump, “Winter’s Key to Future.”

[31] See The Sporting News, September 1, 1973: 31. On August 12, in the game before the doubleheader, Rochester beat Tidewater, 2-1. The Red Wings won the opener of the Toledo twin bill, 1-0. The write-up notes that after the shutout by Weems, Rochester pitchers had allowed just one run in 23 innings.

[32] “Red Wings Sweep Toledo,” Syracuse Post-Standard, August 14, 1973: 13.

[33] “Bunt Spoils Weems’ Bid for Red Wing No-Hitter,” The Sporting News, September 1, 1973: 31.

[34] Seymour S. Smith, “Bird Farmhands Relief Prospects,” Baltimore Sun, September 2, 1973: B18.

[35] Bump, “Winter’s Key to Future.”

[36] Bump, “Winter’s Key to Future.”

[37] “Search Continuing for Weems,” Democrat and Chronicle, January 3, 1974: 27.

[38] Only one other pitcher had reached 11 in the regular season at that point in league history: Roberto Rodríguez Muñoz in 1971-72.

[39] Hetzel phone call #2. The Venezuelan league played until December 23, resumed on the 26th, and continued until the 30th.

[40] Cartwright, “Unheeded Warning Led to Weems Tragedy.”

[41] Ken Nigro, “Birds’ Hood Trains, but Thoughts Are of Absent Pal,” Baltimore Sun, March 13, 1974: C1.

[42] Alfonso Tusa, Una Temporada Mágica, Caracas: Liga Venezolana de Beisbol Profesional (2006): 156.

[43] Cartwright, “Unheeded Warning Led to Weems Tragedy.”

[44] Nigro, “Birds’ Hood Trains.”

[45] Cartwright, “Unheeded Warning Led to Weems Tragedy.”

[46] Nigro, “Birds’ Hood Trains.”

[47] Cartwright, “Unheeded Warning Led to Weems Tragedy.”

[48] Jim Mandelaro, “Death, No-Hitters, and Champagne: The 1974 Red Wings,” Democrat and Chronicle, August 16, 2014.

[49] Nigro, “Birds’ Hood Trains.”

[50] Hetzel phone call #2.

[51] Cartwright, “Unheeded Warning Led to Weems Tragedy.”

[52] Thomas Boswell, “‘Rabbit’ Bounces to Major Leagues as Oriole Coach,” Washington Post, February 6, 1978.

[53] Thomas Boswell, “Miller’s Winding Road,” Washington Post, November 15, 1997.

[54] Cartwright, “Unheeded Warning Led to Weems Tragedy.”

[55] Cartwright, “Unheeded Warning Led to Weems Tragedy.”

[56] Pat Frizzell, “Giant Willow Has No More Reason to Weep,” The Sporting News, February 9, 1974: 45.

[57] “A Mother’s Keepsake,” Democrat and Chronicle, January 18, 1974: 13.

[58] Hetzel phone call #1 and #2. Frank and Charlene Weems subsequently moved to Grants Pass, Oregon.

[59] Hetzel phone call #2.

[60] Nigro, “Birds’ Hood Trains.”

[61] “Bird Prospect Believed Drowned,” Baltimore Sun, January 3, 1974: C4.

[62] Brian Bennett, On a Silver Diamond: The Story of Rochester Community Baseball from 1956-1996 (Scottsville, New York: Triphammer Publishing, 1997), chapter 4.

Full Name

Mark Edward Weems

Born

May 12, 1951 at Seattle, WA (USA)

Died

January 1, 1974 at Patanemo, Carabobo (VEN)

Stats

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.