Moe Hill

“Moe was just scary. The whole league was afraid of him.” – Terry Ryan, future Minnesota Twins GM and teammate of Moe Hill’s in 19731

“A living legend, the Hank Aaron of Class A ball.” – Rick Wolff, a Midwest League opponent of Hill’s in 19742

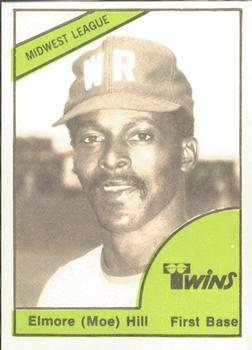

If ever a player personified minor-league baseball, it was Elmore “Moe” Hill. He was a hard-working, hard-playing young man from North Carolina who had one dream: to make it to the big leagues. Unfortunately, he never got there as a player, despite establishing himself as perhaps the Midwest League’s best hitter ever. During 15 seasons in the minors (1965-68, 1970-80), Hill hit 263 home runs—159 of which came in a run of five big years with the Wisconsin Rapids Twins from 1974 through 1978.

If ever a player personified minor-league baseball, it was Elmore “Moe” Hill. He was a hard-working, hard-playing young man from North Carolina who had one dream: to make it to the big leagues. Unfortunately, he never got there as a player, despite establishing himself as perhaps the Midwest League’s best hitter ever. During 15 seasons in the minors (1965-68, 1970-80), Hill hit 263 home runs—159 of which came in a run of five big years with the Wisconsin Rapids Twins from 1974 through 1978.

Yet Hill climbed only as far as Class AA and that for just 56 games in 1971 and 1979. The denial of his advancement remains a mystery. He still rendered ongoing service to the game as a minor-league instructor between 1980 and 2011. In September 2007 he was justly rewarded with a stint in the majors as a coach. This is the story of Hill’s trials and tribulations along the way.

Elmore Hill was born on June 21, 1947, to Raymond and Louveria (Brandon) Hill in Gastonia, North Carolina. The Hill family was composed of nine children: five boys and four girls. Raymond was a machinist, while Louveria was a homemaker.3

Hill played football and baseball at Highland High School, graduating in 1964. He was the first Black to play for an American Legion (Post 23) team in North Carolina. “I know what Jackie Robinson and those guys after him went through because I went through it in Gastonia,” Hill recalled.4

The youngster was only 16 when he graduated, but that didn’t keep several teams—Cincinnati, Minnesota, and Pittsburgh among them—from showing interest. Hill eventually signed with Baltimore and scout Ray Scarborough late in the summer of 1964 for the princely sum of $2,000.

He made his professional debut the following spring in Appleton, Wisconsin, playing for the Fox Cities Foxes of the Class-A Midwest League. The 18-year-old Hill, who batted and threw right-handed, had a nice rookie season, hitting .275 with seven home runs in 107 games. Not bad for a player who was playing one classification higher than he was supposed to. “Actually, I was supposed to go to rookie ball that year, but I got in a few ballgames and did pretty decent, so they kept me at Appleton,” Hill said.5

That winter, Hill played for the Orioles’ team in the Florida Instructional League. He had a slash line of .345/.392/.586 and was second in the league in batting average and slugging percentage. Hill also placed in the top six among leaders in homers and RBIs.

That earned him a promotion in 1966 to Miami of the Florida State League, which was a higher classification of A ball. He performed poorly there, hitting .135 in 89 at-bats. He was sent to Batavia of the New York-Penn League—an unaffiliated team—and heated up there, earning a promotion to Stockton of the California League. Hill struggled there, slashing only .159/.213/.318 in 44 at-bats. That earned him a trip back to Batavia.

In his first game back, he was hit in the face while trying to break up a double play. Hill spent the next three months at Johns Hopkins. “I got a broken nose, a skull fracture and a jaw fracture,” Hill said. “The doctors told me I was lucky to be alive.” The injury had repercussions later in life—he lost sight in his right eye. At the time it didn’t deter him from playing.6

After recovering Hill once again went to Florida for the Instructional League but hit a meager .204 in 93 at-bats. “I didn’t do too well,” Hill said. “I got off to a rough start.”7 His composite stat line for 1966 showed four homers in 305 at-bats and a slash line of .220/.290/.334. Basically, it was a wasted season.

Hill played for Miami in the Florida State League the next two years. Although he struggled in 1967, his next season was better: 23 doubles, 13 triples, and 10 home runs. Hill tied for the league lead in triples, was second in doubles, and placed in the top six in homers, RBIs, and slugging percentage.

Hill sat out the 1969 season because of a stomach disorder, which caused him to lose 20 pounds. He was released by the Orioles during the offseason. The Minnesota Twins picked him up and assigned him to Orlando in the Florida State League for the 1970 season. His Orlando teammates nicknamed him “Creeper” because off the field, Hill didn’t move like a man in a hurry.8 But on the field his swing propelled baseballs posthaste over fences 22 times, setting an Orlando record and leading the league. His 230 total bases also paced the circuit, while he placed second in RBIs (84) and slugging percentage (.474).

In 1971 Hill started the year at Double A with Charlotte in the Dixie Association. However, he played only 11 games there, hitting a paltry .139 with no home runs. Hill was demoted to Lynchburg in the Class-A Carolina League, where he hit seven homers and batted .221 in 76 games. In early August the Twins moved him to the scene of his greatest success: Wisconsin Rapids in the Class-A Midwest League. There Hill showed his power, smacking eight homers in just 78 at-bats.

Hill would spend the next seven seasons in Wisconsin Rapids. He wasn’t promoted at any point, despite hitting 186 homers in that time frame and leading the league four consecutive seasons. He bested future major leaguers such as Clint Hurdle, Willie Aikens, Gary Ward, and Pedro Guerrero.

The hard-hitting outfielder hit 20 homers in 1972, good for third in the league. The following season Hill hit only seven homers but raised his batting average to .271, a 26-point increase over the previous year.

The following spring Hill spent time with a couple of Minnesota Twins players during camp and learned a little about the intricacies of hitting. Those two players were future Hall of Famers Tony Oliva and Rod Carew. “I started talking to Oliva and Carew, and they told me to start looking for (certain) pitches in situations,” Hill said. “And that’s when the power started coming.”9 Did it ever. Hill won the Triple Crown that year, with 32 homers, 113 RBIs, and a .339 batting average. It was one of the best seasons ever by a player in the Midwest League. But it still wasn’t enough to merit a promotion for the slugger.

Extensive firsthand descriptions of Hill’s Triple Crown exploits came from future author, editor, coach, and sports radio host Rick Wolff. In 1974 Wolff played for the Clinton Pilots of the Midwest League. His diary of that season, What’s A Nice Harvard Boy Like You Doing in the Bushes?, devoted a full day’s entry of roughly two pages to Hill and another briefer entry later. Wolff asked, “Why is Moe Hill still in ‘A’ ball?” He further stated, “All that matters is that when we go to the ballpark to play Wisconsin Rapids tonight, we’re going to have to pitch around Moe Hill and not give him any fastballs in game-winning situations if we are to win.”10 That is the kind of respect the Midwest League had for Hill.

Hill was a popular player in the Midwest League and was adored by fans in the mill town of Wisconsin Rapids. He had a habit of playing with a toothpick in his mouth. “It was just something I picked up along the way,” Hill recalled. “I had a different color one for every day.”11

When the 1975 campaign began Hill was back in Wisconsin Rapids, doing time in the Midwest League. Even though Hill was one of the brightest stars in the Twins’ dismal galaxy, his exceptional season didn’t warrant a promotion, and that was a cause for confusion for the 27-year-old slugger. “That’s what was puzzling,” Hill said. “They didn’t tell me anything until I went to them. That’s just the way George Brophy was.” Brophy, who passed away in 1998, was the Twins farm director from 1970-1985. There were several meetings between Brophy and Hill, and the slugger usually walked away with a bad taste in his mouth. “I kept asking the question: Why am I not moving up?” Hill said. “They kept saying, ‘We want you to go back and help the younger players.’”12

Hill almost walked away from the game that year. “Not many people know this, but I almost quit after that year,” Hill said. “I don’t think I ever showed a negative attitude, except for that year.” But after talking over the situation with friends and family, Hill decided to stay in baseball and perform to the best of his abilities.13

He slammed 31 homers in 1975 while hitting a solid .275 for the Twins. Although his season was not as spectacular as the previous campaign, it still was solid by any standard. Even though Hill knew why he was still playing in the Midwest League, he couldn’t help but believe that he was being taken advantage of. Nonetheless, he said, “I just decided to go out and do my job the best that I could.”14 Hill swallowed his pride and did the two jobs he was asked to do—play baseball and mentor young Black players.

While Americans celebrated the country’s bicentennial in 1976 by watching big ships sail into New York’s harbor, Hill worked on his game in the backwaters of the Midwest League at Wisconsin Rapids. He continued to wonder about his situation, but that didn’t affect his play—he smacked at least 30 home runs for the third consecutive year and batted at a .272 clip.

Sometime during this period, the Minnesota Twins were looking for a manager for Wisconsin Rapids, and Hill tossed his hat into the ring. “I asked (to be considered) for the manager’s job,” Hill said. “Brophy had promised me that (the Twins) would consider making me a manager, but they never did. I hate to be negative toward anything, but a couple years later, I was interviewed by Sport magazine. They also interviewed Brophy, and he denied everything. He even denied talking to me (about the manager’s job).”15 So once again Hill wasn’t promoted. Was it because he was Black? We will never know.

But Hill again tried to put all the difficulties behind him, and based on his 1977 season, he was successful. Big Moe (6-feet-2, 190 pounds) smacked 41 home runs—a record for most homers in league history—and knocked in 112 runs, hitting .304 in the process. Hill had led the league in home runs four straight years, led in RBIs in three of those seasons, and even collected a batting title. And what did he have to show for it? Another year in Wisconsin Rapids.

Although he didn’t get the respect he deserved from the Twins organization, he got plenty from the rest of the league. “Dick McLaughlin (then managing the Clinton Dodgers) told me he had a ‘contract’ out on me,” Hill laughed. “It was all in fun. I was just tearing his pitching staff apart.” Those same Dodgers tried to trade for Hill, but the Twins, for whatever reason, were not interested. “The Dodgers tried to make a deal for me,” Hill said. “But I found out later that Brophy would not let me go.”16

Hill played one final year in Wisconsin Rapids and hit 25 homers while batting .279. He was 31 years old and still in Class-A ball. In June a fan wrote to Minneapolis Star Tribune baseball writer M. Howard Gelfand and asked why the Twins wouldn’t give Hill a chance at playing in Minnesota.17 That began a three-month campaign by Gelfand in which he wrote several columns extolling the virtues of Hill and why Minnesota owner Calvin Griffith should call the player up in September. In late August Griffith said, “If it’s humanly possible, I’d like to bring him up. I’m going to do my best to get him in (Minnesota) for a while.”18

Hill, whose minor-league season had ended in late August, stayed in Wisconsin Rapids and waited for the call from the Twins. After 14 years he felt he had a good shot at finally playing in the majors. “It feels good,” he said. “I think there’s a 50-50 chance. It would be a dream come true.”19

There was even talk about having a “Moe Hill Day” at Metropolitan Stadium in Bloomington, Minnesota. The Twins’ advertising agency, Martin-Williams, was eager to promote the special day. The Minneapolis Chamber of Commerce also was looking forward to the promotion and to present Hill with its Outstanding Achievement Award.20

On September 1 Hill’s dream was shattered when Griffith decided not to promote the 31-year-old to the big leagues. Griffith discussed the idea with Brophy and Brophy’s assistant, Bruce Haynes. “They felt bringing up Moe Hill would be an injustice,” Griffith said. “If you did it with him, you’d have to do it with other players who spent so much time in the minors.”21

As if to put an exclamation point on the refusal to call up Hill, the Twins sold his contract to the Kansas City Royals in December. He found out when Royals vice president of player personnel John Schuerholz notified the slugger. “John called me and told me,” Hill recalled. “It was discouraging, and it still is. I don’t have a chip on my shoulder for baseball. I just have a chip on my shoulder for the Minnesota Twins. I had a bitter taste in my mouth. They waited until I was almost 32 when they sold my contract to Kansas City.”22

Hill played in the Royals organization in 1979 at Double-A Jacksonville and was released after 45 games while hitting only .181/.246/.330. The following year he began the season at Single-A Fort Myers as a coach in the Royals chain, but when the team lost several players to injury, he played some games in left field. He was doing well, hitting .364 with two home runs in 18 games, when he collided with shortstop Brad Wellman while chasing a pop fly in a game in late May and suffered a shoulder injury.23 That ended Hill’s season and his playing career.

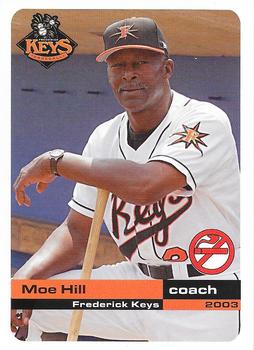

The North Carolina native spent most of the next 30 years in baseball. Hill served as a minor-league instructor and hitting coach in the Royals organization (1980-1984), hitting coach in the Mariners chain (1987-1989), scout and hitting coach in the Cubs organization (1990-1997), and hitting coach and interim manager in the Rangers chain (1999-2002); and finished his post-playing career as a hitting/field coach in the Orioles organization (2003-2011).

The North Carolina native spent most of the next 30 years in baseball. Hill served as a minor-league instructor and hitting coach in the Royals organization (1980-1984), hitting coach in the Mariners chain (1987-1989), scout and hitting coach in the Cubs organization (1990-1997), and hitting coach and interim manager in the Rangers chain (1999-2002); and finished his post-playing career as a hitting/field coach in the Orioles organization (2003-2011).

Prior to the 1991 season Hill was considered for a manager position in the minors for Cincinnati. Howie Bedell, the Reds director of player development at that time, later testified in a trial that he had been blocked by Reds owner Marge Schott from hiring Hill. Two other men also under consideration for similar positions at that time were both hired. Frank Funk and PJ Carey were both white.24

In 2007 Hill finally made it to the big leagues, serving as a coach in September for the Orioles.25 Orioles beat writer Roch Kubatko noted Hill’s close ties to O’s manager Dave Trembley. That October, Kubatko called Hill a strong candidate for the first-base coaching job with Baltimore in 2008.26 “I was politicking for a coaching job for the 2008 season, but they brought in John Shelby from outside the organization, and he got the job,” Hill said years later. “I thought I had a chance to get it, but nope, another turndown.”27 Shelby had played with Baltimore from 1981 to 1987, and Hill thought that might have benefited Shelby. As it developed, Hill returned to the Bowie Baysox, the organization’s Double-A affiliate, in 2008.

In 2010 Hill was invited back to Wisconsin Rapids, where he signed autographs, had his number 24 retired, and threw out the ceremonial first pitch at Witter Field during the inaugural season for the Wisconsin Rapids Rafters, a team in the collegiate Northwoods League. The mayor of Wisconsin Rapids even proclaimed June 7, 2010, as “Moe Hill Day.” Hill returned in 2017 and was honored with a bobblehead celebrating his Triple Crown season of 1974.

Hill was inducted into the North Carolina American Legion Hall of Fame in 2015, along with another Gastonia Post 23 player, teammate and close friend Willie “The Jet” Gillispie. The two outfielders were thrust into roles of being teenage Jackie Robinsons in hostile opponent ballparks.28 A few years earlier, Gillispie recalled being the target of pebbles thrown at him by white boys behind the outfield fence at the Hickory (North Carolina) Fairgrounds in the mid-1960s. “Moe, we gotta do something,” Gillispie yelled at Hill. His older teammate calmly responded, “Play ball, Jet. Just play ball.”29

How good was Hill in his prime? In 1999 Baseball America magazine named Hill the top player in the history of the Midwest League. Back in the mid-1970s Hill dominated the Midwest League for five years. To this day the question remains: Why wasn’t he promoted until he was too old? Much like the punch line on the old Tootsie Pop commercial on TV—the world may never know.

Hill lives in Gastonia with wife Sara. They have two sons, Moe Jr. and Christopher.

Last revised: May 22, 2024

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Moe Hill, who participated in a two-hour phone interview in 2000 and responded via text, plus another phone call, to the author in 2024.

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Will Christensen and fact-checked by Jeff Findley. Thanks also to SABR members John Fredland and Paul Proia for additional research.

Sources

In addition to the sources credited in the Notes, the author consulted Baseball-Reference.com, Retrosheet.org, and Thebaseballcube.com for background information on players, teams, and seasons.

Notes

1 Benjamin Hill, “Hill’s Midwest League stay shrouded in mystery,” MiLB.com, February 27, 2007 (https://www.milb.com/news/gcs-183049).

2 Rick Wolff, What’s A Nice Harvard Boy Like You Doing in the Bushes?, (Hoboken, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, 1975), 184.

3 US Census Bureau, 1950 US Census.

4 Kevin Czerwinski, “King of the Hill,” Ballnine.com, https://ballnine.com/2022/06/27/king-of-the-hill/, accessed February 24, 2024.

5 Moe Hill, telephone interview with author, 2000 (hereafter, the Hill 2000 interview).

6 Czerwinski, “King of the Hill.”

7 Hill 2000 interview.

8 Bill Clark, “Let’s Hear It One More Time for Moe, The Champ,” Orlando (FL) Sentinel, August 27, 1970: 1-E.

9 Hill 2000 interview.

10 Wolff, What’s A Nice Harvard Boy Like You Doing in the Bushes?, 186.

11 Czerwinski, “King of the Hill.”

12 Hill 2000 interview.

13 Hill 2000 interview.

14 Hill 2000 interview.

15 Hill 2000 interview.

16 Hill 2000 interview.

17 M. Howard Gelfand, “Baseball,” Star Tribune (Minneapolis), June 18, 1978: 4C.

18 “After 14 Years, Moe Hill May Play for Twins,” Daily Oklahoman (Oklahoma City), August 29, 1978: 13.

19 Mike McNichols, “After 14 years in minors, Hill may get his shot in the majors,” Wausau (WI) Daily Herald, August 31, 1978: 19.

20 M. Howard Gelfand, “Baseball,” Star Tribune, August 27, 1978: 11 C.

21 M. Howard Gelfand, “Moe Hill won’t get shot at big league,” Star Tribune, September 2, 1978: 1C.

22 Hill 2000 interview.

23 Chris Worthington, “FM Royals sweep two from Orioles,” Fort Myers (FL) News-Press, May 31, 1980: 1C.

24 Tim Sullivan, “Schott faces further trials as charges fly,” Cincinnati Enquirer, November 14, 1992: B-1.

25 Roch Kubatko, “Around the horn,” Baltimore Sun, September 5, 2007: C7.

26 Roch Kubatko, “Hill is in the mix to coach first base,” Baltimore Sun, October 30, 2007: C2.

27 Moe Hill, telephone interview, April 5, 2024.

28 Mike London, “Hall of Famers: American Legion baseball inductees include Gantt, Gillispie,” Salisbury (NC) Post, February 1, 2015: 1B.

29 Mike London, “Salisbury resident is baseball pioneer,” Salisbury Post, March 29, 2011: 1B.

Full Name

Elmore Hill

Born

June 21, 1947 at Gastonia, NC (US)

Stats

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.