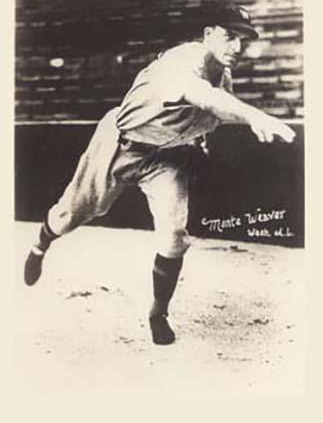

Monte Weaver

Sportswriters treated pitcher Monte Weaver as a curiosity during his nine seasons with the Washington Senators and Boston Red Sox. He was a college professor, a mathematician, a hypochondriac and – most radically – a vegetarian, according to the sports pages.

Sportswriters treated pitcher Monte Weaver as a curiosity during his nine seasons with the Washington Senators and Boston Red Sox. He was a college professor, a mathematician, a hypochondriac and – most radically – a vegetarian, according to the sports pages.

Montie Morton Weaver was born on June 15, 1906, in Helton, North Carolina, a hamlet in the state’s northwestern corner near the present-day Blue Ridge Parkway. His father, Wade, who was born in Virginia about 1872, had a blacksmith shop and later became a farmer. His mother, Mollie, was born in North Carolina. Montie was the youngest of their four children. (There is some confusion about his first name; see notes, below. During his baseball career it was spelled “Monte.”)

The Weaver family moved to nearby Lansing, a town that sprang up along the Norfolk & Western railroad tracks. In 1923 Montie entered Emory & Henry College, a small Methodist school in Emory, Virginia, about 40 miles from home. He pitched for the baseball team, played center on the basketball team, and, because he was 6’1″ tall, joined the track team as a high jumper and pole vaulter. He graduated with honors in 1927 with a major in mathematics and a grade average of “90 or above.” Weaver later told Washington Post writer Shirley Povich that he had applied for a Rhodes scholarship, but lost his chance when the college failed to forward his transcript before the deadline.

He went on to graduate school at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville and taught geometry while earning an M.S. degree in Mathematics in 1929. This became the defining fact of his life for sportswriters; they called him a professor, but the job description was probably more like today’s graduate teaching assistant.

Weaver’s Master’s thesis was titled “The companion to the litnus: the curve whose vectorial angle is proportional to the square of the arc length.” Inevitably, sportswriters would connect this topic to the curveball, no matter how many times he explained that it was an investigation of curves on railroad tracks.

The righthander began pitching for pay in the summer of 1925 with a coal company team in Jenkins, Kentucky – “66 days for $660,” he recalled. That paid his way through college, since his expenses at Emory & Henry amounted to about $450 a year. While pitching semipro ball in Valdese, North Carolina, after graduation in 1927, he impressed several Duke University players. They recommended him to former major leaguer Possum Whitted, the Duke coach, who also managed the Durham club in the Piedmont League.

Weaver pitched for Durham in 1928 and 1929, posting 12 wins and a 1.94 ERA in his second year, then moved up to the Baltimore Orioles of the International League, the highest minor-league level, in 1930. Weakened by appendicitis, he compiled only a 4-6 record. After off-season surgery he won 21 and lost 11 in 1931 and was named to the league’s all-star team.

Washington owner Clark Griffith first spotted Weaver when the Senators and Orioles met in spring training 1931 in Mississippi. Griffith later traveled to Baltimore to scout the prospect. He paid the Orioles $25,000 for Weaver’s contract, crowing, “I regard him as the best minor league pitcher available today.” In his first appearance for Washington on September 20, 1931, the 25-year-old beat the White Sox 6-4.

In a 1932 spring training profile, Shirley Povich wrote that Weaver was trying out professional baseball, rather than being tried out. The pitcher said he could make more money in the majors than teaching, but he would quit rather than go back to the minors. Povich described Weaver as a loner who spent most of his free time walking on the beach or reading the Bible in his hotel room rather than hanging out with his teammates.

The Sporting News headlined Povich’s story “Professor Monte M. Weaver” and referred to him as “the erudite pitching recruit of the Washington Senators.” Throughout the season most stories identified him as “‘Prof.’ Monte Weaver.” (Speaking of names, the Washington club was called “Senators” and “Nationals” interchangeably; “Nats” was popular because it fit easily into a newspaper headline.)

Weaver was the rookie sensation of 1932, winning 22 games. His manager, Walter Johnson (who knew a bit about pitching), commented, “He’s got a great curve ball, one of the best in the league, and enough speed to bust ’em by the batters.”

Starting July 4 Weaver won eight straight decisions. As the wins piled up, he was described as a “lucky” pitcher. His teammates backed him with more than five runs in 14 of his 22 wins, including scores of 15-4, 14-4 and 13-5. But his 4.08 ERA was better than the league average. He finished fifth in The Sporting News Most Valuable Player poll of writers, behind Hall of Famers Jimmie Foxx, Lou Gehrig, Earl Averill and Charlie Gehringer.

The Nats came home in third place with more than 90 wins for the second straight year, but they trailed the pennant-winning Yankees by 14 games. Manager Johnson was fired after the season, though his won-lost record is still the best of any manager in Washington baseball history.

The new manager was Joe Cronin, the 26-year-old shortstop who was married to Clark Griffith’s niece. Cronin and Griffith proceeded to turn over the roster. They dumped the last holdovers from Washington’s pennant winners of 1924-25, pitcher Fred Marberry and first baseman Joe Judge, traded for Earl Whitehill and other pitchers, and brought back the best hitter in the franchise’s history, Goose Goslin, who had a big nose and a big ego to go with his big bat.

New York sportswriter Dan Daniel later reported that the Yankees offered to trade their righthander Red Ruffing for Weaver in May 1933, but Griffith wouldn’t bite. This tale is not as far-fetched as it sounds; although Ruffing went on to a Hall of Fame career, he was not yet an established star in 1933 and was pitching poorly. Daniel repeated the story several times to illustrate the importance of a trade not made.

On April 29, New York was torturing Weaver with “squibs, rollers and pop-fly singles,” Povich wrote. Cronin commiserated, “Don’t worry, Monte, they’re not hitting you hard.” Weaver replied, “I know, Skipper, but they’re tapping the hell out of me.” Povich said that was the first curse ever to escape the pitcher’s lips.

In that game Weaver was the beneficiary of what Povich called “the play of the century.” Lou Gehrig reached base on a topped ball that traveled only four feet. Gehrig advanced to second and Dixie Walker was on first when Tony Lazzeri hit a drive to right-center. Gehrig held up until he was sure Goslin couldn’t catch the ball. Then he took off, with the speedy Walker close behind. The relay – Goslin to Cronin to catcher Luke Sewell – cut down Gehrig at the plate, and Sewell spun around to tag Walker for a double play at home. Clark Griffith said, “Forty-eight years in baseball and I’ve never seen the likes of it before.”

The revamped Nats won the 1933 pennant, the last for a Washington team. Weaver pitched even better than in his rookie season – when he was able. He missed more than a month with a sore right shoulder. Without him, the Nats charged into a pennant race with the Yankees. When he recovered, he contributed six wins to the club’s successful stretch drive, two of them over the Yankees.

That summer Povich commented that Weaver was “given to worrying over every ailment, be it hang-nail or toe-nail.” It was the first mention of what would become a familiar criticism. He also acquired a new sports-page nickname: “Brain Truster” Monte Weaver, after the college professors who advised the new president, Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Weaver finished with a 10-5 record in 21 starts; his 3.26 ERA was ninth best in the league. Cronin chose him to start the fourth game of the World Series, with Washington trailing the New York Giants two games to one. His opponent was Carl Hubbell, that season’s National League MVP, who had beaten the Nats in game one.

After Weaver pitched three perfect innings, the Giants’ player-manager Bill Terry lofted a fly ball into the temporary bleachers in Griffith Stadium‘s short right field for a cheap home run. Washington scored an unearned run in the sixth, and the two starters matched zeroes into extra innings. New York’s Travis Jackson led off the eleventh with a bunt single and was sacrificed to second, bringing up weak-hitting shortstop Blondy Ryan. His solid single to left sent home the go-ahead run. The Nats loaded the bases in the bottom of the eleventh, but Ryan started a double play to end the game. The Giants won the Series the next day on Mel Ott‘s tenth-inning homer. Terry later said Weaver was the Senators’ best pitcher.

Weaver started strongly in 1934 and had won nine games by mid-July. But the Nats lost 11 of his last 13 starts as they sank to seventh place, crippled by injuries to Cronin, catcher Sewell and first baseman Joe Kuhel.

The sporting press turned on Weaver. He had been portrayed as an oddball, but a respected, educated one; now his quirks were blamed for his poor performance, an 11-15 record with a 4.79 ERA. In September The Sporting News labeled him a “hypochondriac” and made the first mention of his vegetarian diet: “addicted to the spinach habit.”

The next spring Washington Star sports editor Denman Thompson wrote that he “does not resemble even remotely the well-built pitcher bought by Griffith from Baltimore five [actually four] years ago. Monte sticks to peas and carrots and passes up the starches and meats so necessary to the profession that is his. As a result the gaunt Weaver has been unusually tardy in hitting his stride and fails to promise much improvement when warmer weather comes.” The Post reported that his weight was down to 146 pounds, from 170 when he broke in.

Other writers of the meat-and-potatoes school ridiculed Weaver. Dan Daniel of the New York World-Telegram wrote, “They tell a strange story about Weaver down in Washington… [A] disciple of a certain school of bone manipulation and starvation came to Monte and sold him the idea of taking treatments – for $500.” According to Daniel, the quack showed Monte an alarming x-ray of his sore back – actually an x-ray of a hunchback – and promised to cure him with a vegetarian diet. Months later he displayed an x-ray of Weaver’s own straight back – “a marvelous cure.” Daniel said Weaver was hooked on the diet, and his weight and his pitching declined.

“It seems you can’t throw strikes on collard greens,” the sportswriter-nutritionist concluded.

Whatever the merits of greens, peas and carrots, Weaver was hammered in his first two starts of 1935. In May he was waived by all other American League teams and sent down to Albany in the International League. Clark Griffith said he was too weak to pitch in the hot weather at the Nats’ other top farm club in Chattanooga.

He returned to the Senators in 1936, insisting that he felt fine, and made the team. He was the “forgotten man” until July, when the pitching staff was struggling and manager Bucky Harris gave Weaver a “desperation” start. He won that game and his next start, then went back to the bullpen. He pitched only 91 innings with a 6-4 record and a better-than-average 4.35 ERA.

Weaver bounced back in 1937. During spring training, Sporting News columnist Dick Farrington reported, “Trainer Mike Martin of the Senators talked like a Dutch uncle to Monte Weaver for three years before finally getting him off that vegetarian diet. After gormandizing [sic] steaks, Monte picked up ten pounds and his fastball this spring.” The Washington Star‘s Francis Stan hailed him as “the big pitching surprise,” and commented that he was “heavier and stronger than at any time since his great ‘freshman year.’” As the Senators finished sixth, his 12-9 record was the best on the team and his 4.19 ERA was better than average. However, he completed only nine of his 26 starts (all A.L. starters completed almost half their games), and the Star‘s Denman Thompson was still referring to his “frail physique” and “lack of stamina.” He could not repeat his success in 1938; starting only 18 times, he won seven games and his ERA swelled to 5.20.

During spring training 1939 in Orlando, Florida, the 32-year-old bachelor met Roberta Clifford, a local elementary-school teacher. “Good we met when we did — Monte was traded to the Boston Red Sox 10 days later,” she would recall. They were married in October 1940. Weaver told Shirley Povich, “Was the oldest bachelor in the league, I guess. Then I gave it a little philosophical thought and popped the question. I began to reckon that the older you get, the more particular you get. But also the less desirable you are. So I got hitched.”

The Senators sold Weaver to Boston for less than the $7,500 waiver price. He started the first game of a Decoration Day doubleheader on May 30, beating the Yankees and Red Ruffing 8-4. It was the last of his 71 big-league victories. Weaver later said the Red Sox had bought him for their Louisville farm club, but they could not waive him out of the league until July.

The onetime professor who had “tried out” baseball was not ready to give it up. He spent the ’39 and ’40 seasons with Louisville before being released. In 1941 he paid his own way to the Baltimore Orioles’ training camp in Haines City, Florida, and was signed by manager Tommy Thomas, his former roommate with the Senators. Pitching in relief for the Orioles, he was hailed as “the International League’s No. 1 comeback.”

Weaver had worked for the United States Army at Fort Belvoir, Virginia, as a civilian logistics specialist in the winter of 1940-41. After Pearl Harbor he enlisted in the Army Air Force and was commissioned a second lieutenant. By 1943 he was managing the Eighth Air Force baseball team in England. He was discharged as a captain.

When he came home from military service, the 39-year-old Weaver said he did not return to teaching because he had been away from it too long. Washington, swollen with war workers, was too crowded to suit him, so he and Roberta moved to her hometown, Orlando. He first had an awning business, a good investment in the days before air conditioning was common, then bought orange groves. He returned almost every year to the North Carolina mountains to see relatives and visited Griffith Stadium at least once for an old-timers game.

In retirement the Weavers moved to a house on Lake Adair in Orlando. Their daughter and son-in-law, Betty and Bruce Saulpaugh, and two grandchildren lived nearby. Their son Brian and his family lived in Vero Beach.

Montie Weaver died at age 87 on June 14, 1994.

Sources

Most baseball encyclopedias give the player’s full name as Montgomery Morton Weaver, but he appears as “Montie” in the 1910 and 1920 census records. His daughter, Betty Saulpaugh, says he never used the name “Montgomery.”

Most information about Weaver’s life and career comes from The Sporting News, the Washington Post and the indispensable www.retrosheet.org.

Al Costello, “Make Mine Beefsteak,” Baseball magazine, June 1937, p. 322.

[Dan Daniel,] “Daniel’s Dope,” New York World-Telegram, undated (1935) and April 21, 1937. Clippings in Weaver’s file at the Baseball Hall of Fame library.

Emory & Henry College archives, Emory, Virginia, provided by R.J. Vejnar II, archivist.

Brent Kelley, “Monte Weaver and the Senators’ last hurrah,” Sports Collector’s Digest, March 20, 1992, p. 270.

Henry W. Thomas, Walter Johnson: Baseball’s Big Train. Phenom Press, 1995.

U.S. Census, Ashe County, North Carolina, 1910 and 1920.

University of Virginia Alumni Records, Charlottesville, Virginia.

Clarice Weaver of West Jefferson, North Carolina, interview, August 13, 2004. Mrs. Weaver’s husband is Monte’s nephew and she met him many times. She is a member of the Ashe County Historical Society.

J. Russell White, “Math, Mound Both Part of Pitcher’s Past,” Orlando Sentinel, July 29, 1993, p. 13.

(No byline), obituary, Orlando Sentinel, June 16, 1994, p. B4.

Full Name

Montie Morton Weaver

Born

June 15, 1906 at Helton, NC (USA)

Died

June 14, 1994 at Orlando, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.