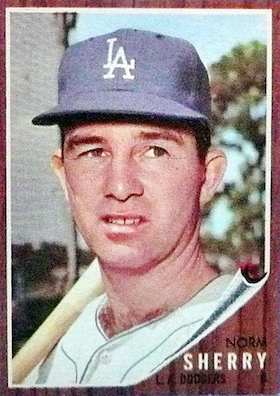

Norm Sherry

Right-handed reliever Larry Sherry captured the 1959 World Series Most Valuable Player award after he appeared in all of the Los Angeles Dodgers’ four post-season wins, receiving credit for the last two. Four years previously, the then 19-year-old considered quitting after a miserable season in the Piedmont League (Class B). He was talked out of it by catcher and older brother Norm Sherry. Following a similarly challenging campaign in the Pacific Coast League in 1958, Norm once again came to the rescue. “He was a smart catcher,” Larry said. “[H]e can spot a flaw in my delivery quicker than anyone.”1 Via Norm’s tutelage Larry developed a slider that launched the righty’s major league career and led to the 1959 Dodgers post-season success.

Right-handed reliever Larry Sherry captured the 1959 World Series Most Valuable Player award after he appeared in all of the Los Angeles Dodgers’ four post-season wins, receiving credit for the last two. Four years previously, the then 19-year-old considered quitting after a miserable season in the Piedmont League (Class B). He was talked out of it by catcher and older brother Norm Sherry. Following a similarly challenging campaign in the Pacific Coast League in 1958, Norm once again came to the rescue. “He was a smart catcher,” Larry said. “[H]e can spot a flaw in my delivery quicker than anyone.”1 Via Norm’s tutelage Larry developed a slider that launched the righty’s major league career and led to the 1959 Dodgers post-season success.

Norm Sherry would go on to assist two Hall of Famers, one of whom is considered the greatest left-handed hurler in history: “The world will little note nor long remember Norm Sherry,” reported The Sporting News in 1971. “[B]ut [on March 23, 1961] Norm played a part in [Hall of Famer Sandy] Koufax’s conversion from a marginal liability to a major asset. ‘Why not have some fun out here, Sandy?’ said Sherry [after the flamethrower walked the bases loaded on 12 pitches in a “B” squad exhibition in Orlando, Florida]. ‘Don’t try to throw so hard’ . . . [In 1961] Sherry [was] the right man with the right way to phrase the right thought at the right time.”2 Seventeen years later he took a young Gary Carter under his wing and helped him develop into a Hall of Fame catcher.

Despite these and many more contributions Sherry, a major league catcher for five years and later manager for portions of two, rarely got noticed beyond, “Oh yeah, you’re Larry Sherry’s brother, aren’t you?”3

Sherry was born on July 16, 1931, the second of four sons of Harry Scharaga Sherry and Mildred “Minnie” (Walman) Sherry, in New York City. Both sides of the Sherry family were Jewish immigrants from Russia, and Sherry’s maternal great grandfather was a rabbi. The two branches escaped separately in the wake of the anti-semitic pogroms that followed the 1881 assassination of Czar Alexander II. Portions of the Walman family immigrated to Europe, and in 1900 Sherry’s mother was born in London, England. A year later she moved with her family to the United States. More than a century passed before Sherry learned that other of his forbears who settled on the European continent perished in the Holocaust.4 Sherry’s paternal grandparents, Max and Sarah Scharaga, arrived in the United States with their newborn daughter in 1898. They initially settled in New Jersey where three sons, including Sherry’s father Harry, were born. Around 1920, Harry and at least one of his brothers changed their surname to Sherry.

Harry entered the dry cleaning business. Excepting a short stint as a studio worker in Hollywood around World War II, he continued in the cleaning profession after moving to California in the 1930s. His wife Mildred was a seamstress and milliner. Their youngest son Larry was born in the Golden State. Sports played an integral part in their sons’ lives with both Norm and Larry gravitating to basketball while all four enjoyed baseball. Three of the four boys would go on to play baseball professionally. “We lived about three houses from . . . Fairfax High School in Los Angeles. We were constantly jumping the fences and playing on the grounds . . . And we were not but three or four blocks from Gilmore Field, where the Hollywood Stars of the Pacific Coast League used to play . . . I knew all the guys that played . . . Frank Kelleher, Tony Lupien.”5

The boys achieved success on varied prep school, American Legion, and later semi-pro diamonds. Thus in 1950, after high school, Sherry found himself bound for the University of Southern California under a full baseball scholarship. But then came a Brooklyn Dodgers’ tryout at Gilmore Field, and scout Howie Haak signed Sherry, and the kid was assigned to the nearby Santa Barbara affiliate (Class C). The youngest player on the roster, Sherry’s strong right arm made a deep impression on the team management, who briefly considered turning him into a pitcher (the pursuit taken up by his younger brothers George and Larry). Instead he spent most of the 1950 season behind the plate.

Jumped to Double-A ball in 1951, Sherry struggled (.077 in 65 at-bats), and he didn’t play much behind the Fort Worth Cats catcher-manager Bobby Bragan. In late May Sherry was optioned to the Newport News Dodgers in the Piedmont League where he finished the season. Then came a two-year hiatus while he served in the US Army’s 4th Infantry Division in Frankfurt, Germany..

Released from the service in February 1954, Sherry was reassigned to Newport News. A 1-for-42 slump marred his return though. He broke out notably with a ninth inning homer that ruined a May 6, 1954, perfect game bid by Lancaster righty William Riale. Four months later Sherry came up a home run shy of the cycle as he led the Dodgers to a 10-5 win over the Portsmouth Merrimacs. The right-handed hitter finished among the team leaders in hits (98) and home runs (12). In February 1955, Sherry was invited to the Brooklyn Dodgers’ advance training in Vero Beach, Florida under manager Walt Alston. Sherry was one of eight players—including future Hall of Famer Don Drysdale—to continue training with the parent club as a non-roster invitee.

He was assigned to Fort Worth just one week before the start of the 1955 season. Sherry had barely arrived in Texas when he was sidelined with an injury to his right arm. Bone chips had to be surgically removed from his elbow, and he was held to just 200 plate appearances for the season. Injuries continued to plague Sherry over the next two years. He began the 1956 season recovering from offseason back surgery and had his arm broken by a pitched ball the next year. The injuries affected both his batting line (a .228-2-28 average in 1956-57), as well as his personal life: the broken arm came one day before he married California native Marty Brockway.

Despite the injuries, Sherry remained a prized prospect in the Dodgers chain. Again a non-roster invitee to spring training in 1958, the 26-year-old’s chances had been greatly enhanced following Roy Campanella’s career-ending automobile accident in January of that year. “Sherry had the best arm of any catcher I ever saw,” said farm director Fresco Thompson. And he “can hit as well as any catcher in the majors except the top men.”67 On March 10, 1958, Sherry and his brother Larry (signed by the Dodgers in 1953) formed the Dodgers’ battery in a grapefruit league exhibition against the Milwaukee Braves, probably for the first time the brothers paired since semi-pro ball years earlier. Two years later the brothers made it official by becoming the 11th (and last), and almost certainly the only Jewish, brother-battery in major league history.8

Both were eventually assigned to the Spokane Indians in the Pacific Coast League. On April 27, Norm once again played spoiler when his base hit deprived Vancouver Mounties righty George Bamberger of a no-hitter. Two months later Sherry’s 13-game hitting streak (a blistering .510 pace in 49 at-bats) earned him an All Star berth, and by the time of the game he stood among the league leaders with a .313 batting average. Though he slowed in the season’s second half, Dick Walsh, the organization’s vice-president tabbed him for a roster spot on the parent club in 1959. Norm and Larry spent the winter playing in Venezuela for the Cabimas Oilers; on November 15 Norm’s home run aided Larry in his first Occidental Winter League win. A month later Norm got his first taste as manager after skipper Pete Reiser returned stateside. He was runner-up in the circuit’s home run crown to North Carolina native Billy Queen.

Lofty projections by team vice-presidents notwithstanding, Sherry’s stay with Los Angeles was brief. On April 12, 1959, he made his major league debut in Chicago. (Joe Pignatano, the Dodgers’ backup catcher, appears to have begun the campaign nursing a minor injury; he did not make an appearance behind the plate until two weeks into the season.) Sherry was on the receiving end of an erratic Koufax who did not survive beyond the 3rd inning. Cubs southpaw Taylor Phillips was no less erratic, hitting Sherry with a pitch in his first plate appearance. Sherry retaliated with a two-run single in his first official at-bat. But once Pignatano healed up, Sherry was reassigned to Spokane. He produced no All Star campaign this time, though. His contributions were sliced by more than 20 percent after he contracted pneumonia in June. But he had displayed enough promise to earn a late-season call-up, and on September 22 he made his second major league appearance as a late-inning defensive replacement.

After the season Sherry again proceeded south, this time to the Dominican League with a large contingent of players from the Dodgers’ organization (most prominently Frank Howard, though it appears Larry Sherry, the 1959 World Series hero, did not join this trek). The season played out nearly the same as the preceding winter’s, with Sherry taking the Escogido Lions’ managerial reins from skipper Pete Reiser. On November 23, Sherry almost single-handedly led the Lions to victory, knocking in four of the five runs in a shutout over Licey. He earned an All Star berth while piloting his club to a league championship. And the following year, in what appears to be his last in winter ball, Sherry was hired as the Lions’ manager from the start.

Throughout his long tenure as the Dodgers’ manager Walter Alston rarely deviated from his two-catcher policy; in only six of his 23 years did the Hall of Fame skipper employ more than two backstops for more than 25 games. Two of those six years came during Sherry’s employ. Why Alston chose to carry three catchers in 1960 isn’t clear, but it appears to have been insurance against starter John Roseboro’s offensive drop the preceding year As events unfolded, the veteran backstop would slide even further this season. Roseboro entered a May 7, 1960, contest against the Philadelphia Phillies mired in a 0-for-17 slump. In the seventh inning Alston lifted him in favor of Sherry. Four innings later Sherry smashed a walk-off homer to give his brother the win (the aforementioned brother-battery game). (Though the brothers maintained a close relationship throughout their lives, in 1959 sportswriters detected an intense competitive streak between the pair after Larry threw a knockdown pitch at his brother during an intra-squad game; “[on the field] they treat each other as if they were not related at all.”9)

Three days after the walk-off homer Sherry earned his first starting assignment of the season and clubbed another home run in a losing cause. He followed this with a game winning grand slam on May 31 against St. Louis Cardinals hurler Ron Kline. Sherry thrived in Los Angeles’ Memorial Coliseum, the club’s four-year home before Dodger Stadium was built. Sherry was adept at hitting balls over or against the 42-foot tall left field screen “wall,” a mere 251 feet from home plate. (He had a .297/.359/.526 line with 11 HR and 30 RBI in 175 career at-bats including the last homer hit in the cozy confines on September 20, 1961). Alston turned increasing to him at home until a pitched ball fractured Sherry’s wrist on August 22, ending his season. In less than half Roseboro’s at-bats during the 1960 campaign, both home and away Sherry produced a line of .283/.353/.500 with 8 HR and 19 RBI; Roseboro’s .213/.323/.369 with 8 HR and 42 RBI.

Sherry’s hopes of stepping into a first-string role the next year were extinguished by an injury-plagued 1961 season. Ten games in he was taken from the field on a stretcher after Phillies pitcher Curt Simmons barreled into him at the plate. Sherry suffered internal bleeding from a kidney laceration, spending a week in the hospital and a considerable amount of time recuperating at home. His May 17 return featured a home run off future Hall of Famer Warren Spahn. Seven weeks later Sherry was warming up a pitcher in the bullpen when Roseboro pulled a foul ball that struck him, fracturing a rib. A sore arm ensued after his August return. “It was like going through three spring trainings for me in 1961,” Sherry recalled. “No wonder my arm went sour. I never did get in good condition after the first injury.”10 On September 4, he tied a major league record for catchers with an unassisted double play. But he only got 121 at-bats for the season.

After Roseboro’s 1961 rebound season, Sherry’s hopes of competing for the starter’s role in the Dodgers’ 1962 spring training pretty well died. “I’m completely satisfied with [Sherry] as my second-string catcher,” Alston said.11 But injuries still dogged him. A bad back limited him to but a single appearance from July 4 to August 5. Four days later, Sherry made his final appearance as a Dodger before a knee injury ended his season. On October 11, the New York Mets bought him along with outfielder Dick Smith for $60,000.

During 1963 Sherry split time with four other Mets catchers. The back injury followed him to New York and greatly hampered his hitting. He suffered a 0-for-29 stretch, for example, before Memorial Day. Midsummer talk of his being involved in a seven-player swap with the St. Louis Cardinals came to naught.. One of his few highlights came against the Houston Colt 45s on July 16 with a pinch-hit, walk-off RBI single. On September 26, he faced his brother for the first and only time in the majors. Ironically, it also proved to be Sherry’s last big league game. When the season ended he was sent to the Buffalo Bisons in the International League.

Sherry did not sign a contract with the team until days before the start of the 1964 season. He strongly considered a coaching proposition from the Dodgers, who offered utility infielder Marv Breeding to the Bisons in order to place Sherry on the sidelines with Spokane manager Danny Ozark. When the deal fell, through the Sherry suited up one last time in hopes of returning to the majors. He built a strong case with a .310 average in the first few weeks of the season, including a two-homer, four RBI game against the Atlanta Crackers on May 1. (Interestingly Sherry’s offensive outburst came against southpaw Jim Merritt whom Sherry had last seen as the Dodgers’ clubhouse attendant years before). Though his offensive would slide, Sherry did manage to stay injury-free and got more play than he’d received since 1959—100 games in a three-catcher platoon. He finished with a .232/.301/.349 line with 7 HR and 43 RBI in his last season as a full time player. He was 31 years old.

The Dodgers hired Sherry within weeks of his retirement. Instead of bringing him on as a coach, the club assigned him as manager in the same city where he began his professional career: Santa Barbara, California. It was a “real pleasure to be coming back,” Sherry joyfully declared.12 A three-year stint ensued in which he ushered along the careers of many notable players including his first Opening Day starter, future Hall of Famer Don Sutton. At various times Sherry was forced to write his own name in the lineup when injuries decimated his catching corps. Before his departure in 1967, Santa Barbara honored him with a new set of golf clubs during “Norm Sherry Night,” an event attended by Sandy Koufax.

Sherry spent a year scouting for the New York Yankees in southern California before being hired by the California Angels in 1969. Initially brought on as a scout and instructor, he ended up managing the club’s Idaho Falls affiliate in the Pioneer League. By year’s end the Angels added him to their coaching staff (the strong Dodgers influence of manager Lefty Phillips and coach Pete Reiser prevailed over an offer from Cincinnati manager and fellow California League skipper Sparky Anderson to join the Reds’ staff). The following season on a flight from Anaheim to Kansas City in September 1970 Sherry nearly came to blows with a 23-year-old pitcher teammate Greg Garrett, a proverbial hothead who was believed to have led the club in fines and was gone by the end of the year. Sherry, however, was no stranger to intermural conflict. In 1965 he had engaged in a fight with a much younger Bakersfield Bears’ outfielder named Mik Mehas.

In October 1971, the Angels released Phillips and their entire coaching staff. The next year Sherry spurned a lucrative business offer to remain in baseball, accepting a job as manager of the Angels’ Texas League affiliate in Shreveport, Louisiana. He stayed in the same circuit in 1973, moving to El Paso, Texas, when Shreveport aligned with the Milwaukee Brewers. In 1974 Sherry was promoted to the AAA Pacific Coast League, a move that suited him fine: “[T]he travel is better,” he joked. “[T]aking a plane to Hawaii will beat riding a bus to Alexandria [Louisiana] anytime.”13 The following year Sherry led the Salt Lake City Gulls to the circuit finals, a masterful job of managing when no fewer than 16 of his players were shuttled between Utah and Anaheim during the season.

In 1976 the Angels promoted Sherry to serve as third base coach under fiery manager Dick Williams, a future HOF skipper and the club’s fifth hire in eight years. Mired in last place, Williams’s brief tenure ended on July 23 after a near-fight erupted between him and third baseman Bill Melton on the team bus. Sherry learned he was the Angles’ new manager from a radio broadcast the next day. Variously described as honest, uncomplicated, and low key, Sherry was immensely popular with the players. “It seemed like a new atmosphere on the club when he took over,” said outfielder Dave Collins. “[E]verything was better. We can play without worrying about getting jumped on.”14 In his major league managerial debut on July 24, Sherry led the Angels to a doubleheader sweep of the Texas Rangers, and a series sweep the next day. His ball club moved out of the cellar in August and finished in fourth place after a .636 winning percentage in their last 33 games (a remarkable feat for the AL’s worst offense). Despite this success, rumors about a complete management makeover were circulating, and whether Sherry would be retained after the season was doubtful. Moreover, the Rangers’ recently fired skipper Billy Martin had reportedly approached the Angels’ owner offering to take over the helm.

But when general manager Harry Dalton and his staff were retained after the season, the current on-field management staff was spared the ax. Before engaging in the offseason free agent pool, Dalton’s first move was to hire Sherry for the 1977 season. Referring to the one-year contracts of his former skipper, an elated Sherry said, “I hope I’m the Walter Alston of the ‘70s, ‘80s and ‘90s.”15 And the skipper’s expectations quickly vaulted to championship-level heights when Dalton, over a nine-day period in November, spent a then-lofty $5.2 million to acquire All Star free agents Don Baylor, Joe Rudi, and Bobby Grich.

In 1977 Sherry and Grich appeared on the forgettable television program The Gong Show16 while the balding skipper also appeared in a TV commercial for a toupee company (and wore a hairpiece his wife despised because she thought it made him look like sportscaster Howard Cosell). Regrettably, these events represented a couple of the few highlights that year for Sherry and his team. “[L]eading the Hospital League by miles,”17 Sherry was fired on July 11 after the Angels plummeted to fifth place following a dismal five-game losing streak. “I think it is an injustice to Norm. Overall, he deserved a better fate,” said future Hall of Famer Nolan Ryan. “We didn’t play well. And there were the key injuries. . . . He tried everything to shake us up.”18 Sherry finished the year scouting for the Angels.

In 1978 Montreal manager Dick Williams brought Sherry on to the Expos’ staff. Serving as the third base coach, Sherry was assigned the additional responsibility of tutoring slugger Gary Carter on a catcher’s defensive responsibilities. “It’s a good thing,” Carter said. “I definitely don’t feel that I’m 100 percent behind the plate. . . . I’m looking forward to working with Sherry.”19 Excepting 1982, the catcher logged the most games of any one season throughout his 19-year Hall of Fame career.

Sherry remained in Montreal with Williams through 1981 and followed him to San Diego the next year. At the end of the 1982 season Sherry was interviewed for the Rangers’ vacant manager’s slot (a job that went to Doug Rader). Serving as the Padres’ pitching coach, he tutored the staff that helped capture the franchise’s first World Series berth in 1984. But because his heavy hands-on approach disconcerted some of his staff Sherry was released the day after the Series. Two years later he joined the San Francisco Giants’ staff under the helm another former Dodger, Roger Craig. In 1989, the club made its first World Series berth in 27 years thanks to “the master juggling act by Manager Roger Craig and pitching coach Norm Sherry.”20 Sherry remained with the Giants through the 1991 season.

Around 1982 Sherry’s marriage to Marty dissolved in divorce. The union produced three children, two girls and one boy. Sherry had two brushes with death: undergoing open heart surgery in November 1978 and suffering a heart attack in March 1981. Decades later he was able to enjoy the company of nine grandchildren and four great-grandchildren. In December 1985, he married Linda Chadwick, and this marriage lasted more than 30 years. The couple settled in San Diego where Sherry pursued his favorite pastimes, bowling and golf. On February 13, 2011, Sherry was the guest speaker at the San Diego Jewish Film Festival for the screening of “Jews and Baseball: An American Love Story.”21 Throughout the years he cherished the opportunities to reunite with former teammates. In 2014, for example, Sherry was present in Petco Park when the Padres’ celebrated the 30th anniversary of the team’s first World Series.

Though Sherry constructed a mere .215/.279/.346 line with 18 HR and 69 RBI in five major league seasons, his contributions to the game were far greater. Sherry spent more than 40 years in baseball and helped to usher along many players’ careers, including those of his brother, Sandy Koufax, and Gary Carter.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank Tom Schott for review and edit of the narrative.

Sources

Ancestry.com

Norm Sherry, telephone interview, February 1, 2016

Notes

1 “Sherry Lops Off Suet, Seeks Job in Bullpen,” The Sporting News, March 29, 1969: 21.

2 “Sandy Started Slowly … But Oh What a Finish,” ibid., August 14, 1971: 16.

3 “Sherry Already Can Boast One Miracle,” ibid., 1976: 9.

4 Hillel Kuttler, “A Koufax teammate discovers unknown relatives in England,” The Times of Israel, November 8, 2015; accessed February 25, 2016, http://www.timesofisrael.com/a-koufax-teammate-discovers-unknown-relatives-in-england/.

5 Lou Hernandez, Memories of Winter Ball: Interviews with Players in the Latin American Winter Leagues of the 1950s (Jefferson, NC: McFarland Publishing, 2013), 85.

6 “Norm’s Lame Wing Kept Sherry Brother Battery Intact,” The Sporting News, February 14, 1962: 7.

7 “’Weak Spots Can Trip Braves’ – Fresco,” ibid., March 19, 1958: 2.

8“Brother Batteries,” Baseball Catchers; accessed February 25, 2016, http://bb_catchers.tripod.com/catchers/brother_batteries.htm

9 “Never Feud, Sherrys Behave Like Non-Relative in Game,” The Sporting News, May 18, 1960: 2.

10 “Norm’s Lame Wing Kept Sherry Brother Battery Intact,” ibid., February 14, 1962: 7.

11 “Dodgers’ Blue-Chip Flag Stock Skyrockets in Swap for Carey,” ibid., April 4: 22.

12 “Caught on the Fly,” ibid., February 27, 1965: 34.

13 “Sherry Enjoys Triple A,” ibid., July 6, 1974: 36.

14 “Execs Safe . . . But Sherry? Angels Silent on Manager,” ibid., October 9, 1976: 16.

15 “Williams No Angel, Sherry Moves Up,” ibid., August 7: 16.

16 M.J. Lloyd, “Bobby Grich and Norm Sherry Pimp The Gong Show In 1977,” Halo Hangout, December 21, 2011; accessed February 25, 2016, http://halohangout.com/2011/12/21/bobby-grich-and-norm-sherry-pimp-the-gong-show-in-1977/.

17 “Angels Feel Guilty as Sherry Feels the Ax,” The Sporting News, July 30, 1977: 13.

18 Ibid.

19 “Millionaire Carter Returns to Work Bench,” ibid., March 18, 1978: 51.

20 “The Giants’ Subtle Difference,” ibid., October 2, 1989: 12.

21 Kendra Hartmann, “Jewish Film Festival hits the silver screen,” sdnews.com, February 24, 2011; accessed February 25, 2016, http://www.sdnews.com/view/full_story/11247456/article-Jewish-Film-Festival-hits-the-silver-screen?instance=update1 )

Full Name

Norman Burt Sherry

Born

July 16, 1931 at New York, NY (USA)

Died

March 8, 2021 at San Juan Capistrano, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.