Oscar Jones

Oscar Jones was a man of many talents. In 1903, the Brooklyn Eagle listed them: “all around ball player, champion bicycle rider, sprinter, boxer, tumbler, gymnast, wrestler, cartoonist and cigarmaker.”1 To this list can be added showman, draftsman, farmer, and tire repairman.

Oscar Jones was a man of many talents. In 1903, the Brooklyn Eagle listed them: “all around ball player, champion bicycle rider, sprinter, boxer, tumbler, gymnast, wrestler, cartoonist and cigarmaker.”1 To this list can be added showman, draftsman, farmer, and tire repairman.

As a pitcher, Jones won close to 300 games in a 15-year professional career from 1900 to 1914.2 On the Brooklyn Superbas of the National League, he won 44 games from 1903 to 1905. In the minors on the Pacific Coast, he won 20 or more games in seven seasons, including three seasons with 30 or more wins. When not pitching, he was often on the coaching lines delighting the crowd with handsprings, cartwheels, and backflips. He wasn’t just a pitcher; he was a “pitcher-acrobat,” said the Los Angeles Record.3

Oscar Lafayette Jones was born on October 22, 1879, in Carter County, Missouri. He was the elder child of Shadrack “Shade” Jones and Martha “Mattie” (née Coil) Jones; he had a sister Olive. The family moved to Phoenix, Arizona Territory, about 1888. According to US Census records, Shade was a hotelkeeper in 1880 and a farmer in 1900. Mattie died in 1895, and Shade remarried.

In his late teens, Oscar was a champion bicycle racer. Dubbed “the Phoenix flyer,” he set an Arizona record for fastest time in a half-mile race.4 Further, in a traveling circus, he performed bicycle tricks and acrobatic stunts.5 At age 20, he turned his attention to professional baseball, and in 1900 he pitched for three teams in California (San Bernardino, Hanford, and Oakland)6 and for Great Falls in the Montana State League.

After helping Great Falls win the league’s second-half title, Jones was instrumental in the team’s postseason triumph over rival Helena, the first-half champion. He was the winning pitcher in the first game and losing pitcher in the third game of a tumultuous best-of-five playoff series.7 Great Falls won Game Four by forfeit in Helena on October 4, 1900, evening the series at two games apiece. In that game, Jones pitched and Great Falls led 7-0 in the third inning when umpire Eddie Burke ejected Helena’s Joe Tinker, the future Hall of Famer, for offensive language. Enraged Helena fans rushed onto the field and attacked Burke. His “face was cut, bruised and bleeding” before “some of the decent men in the crowd” protected him from the mob.8

The teams played the fifth and deciding game the next day at Butte, Montana, despite inclement weather described as “a sea of slush, hail, storm, snow and rain.”9 At 5,500 feet elevation, Butte was hardly ideal for a late-season game, but it was a neutral site agreed upon by the combatants. Jones was again called on to pitch; he endured the sloppy conditions, and Great Falls prevailed to win the pennant.

Baseball in California was surely more enjoyable. Pitching for San Bernardino on March 3, 1901, Jones waged a classic 15-inning pitchers’ duel with San Diego’s Luther Taylor.10 Though Jones lost, 1-0, his impressive performance earned him a contract with the Los Angeles Angels of the California League. He pitched the season opener on March 31 and allowed only two hits in a 1-0 loss to Oakland.11 Four days later, he went the distance in a 12-inning victory over Oakland.12

Jones stood 5-foot-7, weighed 163 pounds, and was described as stocky. He was a right-handed pitcher. (Sources disagree on whether he was a right- or left-handed batter.) His fastball was intimidating.13 Also, batters were wary of swinging at Jones’s “swift and deceptive curves, which foul off so naturally.”14 The “foul strike” rule was in effect in 1901, which dictated that a foul with fewer than two strikes was counted as a strike.15

On May 26, Jones hurled a three-hit shutout to defeat Oakland,16 and he allowed only five hits in blanking San Francisco on July 5.17 He was again a “great enigma” to Oakland on July 14 as he pitched and won both games of a doubleheader.18

On the sidelines Jones “turned various kinds of handsprings and was as agile as a monkey,” bringing “bursts of laughter” from players and fans.19 Baseball was a show. Harkening back to his days in the circus, Jones was both athlete and entertainer.

He was a talented sketch artist. Displaying yet another side of him, his charming, cartoonish drawings of ballplayers were published in August by the San Francisco Examiner.20

In 470 innings pitched, Jones compiled a 29-24 record for Los Angeles in 1901. In the offseason he worked as a cigarmaker in nearby Pomona,21 and he returned to the Angels in the spring of 1902. His second season was even better than his first: He appeared in 66 of the Angels’ 174 games and achieved a 36-25 record. His 36 wins were the most in professional baseball that year, according to Baseball-Reference.com. Signed by the Brooklyn Superbas, he headed to the majors.

Jones debuted on April 20, 1903, at the Polo Grounds by pitching all 11 innings of Brooklyn’s 5-5 tie against the New York Giants. In his second start three days later, he earned his first major-league win by defeating the Philadelphia Phillies, 4-2, in Brooklyn. He delivered his first shutout, a three-hitter at Cincinnati, on June 10; his pitching that day “sparkled with brilliancy throughout the entire nine innings.”22

Brooklyn manager Ned Hanlon was proud of him. “He’s an all-around athlete,” said Hanlon, and is the “fastest man on his feet in the National League.”23 Jones was willing to race anyone in a 100-yard dash.

During a game in May, Jones was “chased off the coaching line” by umpire Augie Moran for turning a handspring. Dismayed by this killjoy, the Brooklyn Standard Union quipped, “Hereafter Umpire Moran will require all players … to wear full dress suits and talk in a whisper.”24

Umpire Hank O’Day tolerated Jones’s sideshow, which brought life to a listless game in St. Louis on July 18. When Jones “is on the coaching line he introduces enough new features to warrant the price of admission,” reported the St. Louis Republic. “Not since the days of Arlie Latham has a coacher used such original methods along the side lines as Jones. At dull moments, when the game was dragging, Oscar would oblige the spectators by a series of thrilling handsprings and flip-flops that always brought the crowd to their feet.”25

Jones’s rookie season was a success: a 19-14 record with four shutouts and a 2.94 ERA. He carried a heavy workload for Hanlon’s fifth-place team; his 324 1/3 innings pitched ranked fourth in the National League.

The next year, Jones carried a heavier load: 377 innings pitched, second most in the league. His disappointing 17-25 record was due in part to Brooklyn’s anemic offense: the team’s runs-per-game average dropped by one-third from 4.8 in 1903 to 3.2 in 1904. Twelve of his 25 losses were by one run. On August 11, in one of his finest performances, he went the distance but lost, 4-3, in a 17-inning pitchers’ duel with the Cardinals’ Kid Nichols.

“Though I did not win so many games [in 1904], I don’t think I ever pitched better in my life,” said Jones. “I seemed to have more this year than ever. I had a spitball this year and a good one, and it helped me out of many a hole.”26 Jones said he was taught to throw the spitball by National League pitcher Frank Corridon.27

After Brooklyn’s season ended in early October, Jones pitched another 93 1/3 innings for Los Angeles at the tail end of the Pacific Coast League (PCL) season. That made a total of 470 1/3 innings pitched in 1904. He returned to Brooklyn in 1905 but had an off year. Through the games of June 20, 1905, his season record was 7-8, quite good considering Brooklyn was in last place with a dismal 17-40 mark. But after June 20, he won only one of eight decisions.

He complained publicly that he wanted out of Brooklyn.28 Hanlon gave him his wish by releasing him on August 24, and he finished the year with Seattle in the PCL. His major-league career was over. Henceforth, he pitched only on the West Coast.

Jones reeled off consecutive stellar seasons in the PCL, going 31-23 in 499 2/3 innings for Seattle in 1906 and 29-22 in 458 2/3 innings for San Francisco in 1907. A notable highlight was his shutout of Portland on Opening Day, April 6, 1907.29 That game was played at newly constructed Recreation Park in San Francisco, replacing the old Recreation Park, which was destroyed by the 1906 earthquake. On October 19, 1907, fans enjoyed twin sideshows at the new ballpark. While Jones performed backflips on the first-base coaching line, his teammate Larry Piper did the same on the third-base side.30

In Jones’s estimation, a faster fastball and new change of pace made him more effective in the PCL than during his time in the National League.31 He shut out Portland on Opening Day, April 4, 1908, in San Francisco.32 But he was inconsistent throughout the 1908 season and posted a lackluster 11-24 record. Some observers believed he was washed up, and even Jones doubted that he could continue to compete in the PCL.33

Jones was married in 1906.34 In January 1909, he went with his wife Margaret (née Conroy) to Calexico, California, on the Mexican border, for two reasons: to pitch for the Calexico team in the winter Imperial Valley League and to work as a draftsman for a hydrological engineering firm. He fanned 20 batters in his first game for Calexico, though the same opponent beat him, 7-1, a week later. Margaret served as an official scorer in the league.35 His engineering manager said Jones was an excellent draftsman and seemed to prefer drafting over baseball.36

For the 1909 season, Jones broke his contract with San Francisco by signing with Santa Cruz in the independent California State League. This got him branded as an “outlaw,” and he was blacklisted by professional baseball; however, the move revived his career. Facing weaker competition, he was the most dominant pitcher in the California State League. In 451⅔ innings, he achieved a remarkable 39-14 record with nine shutouts. He was 25-6 for the Santa Cruz club, which disbanded in July, and 14-8 for Fresno.37

Against Stockton that year, Jones was a perfect 13-0. It is “his peculiar style of delivery,” explained Stockton manager Macdonald Douglass. He “turns his back on the batsman, describes a circle with his right arm and almost turns himself upside down. Then suddenly he turns around and shoots the ball over the plate before you know it’s coming.”38 Though unconventional, it was a smooth overhand delivery, not herky-jerky, and pleasant to watch.39

In 1910 Jones again pitched for Fresno in the California State League, and he had a 16-8 record when the club disbanded in June. He then traveled the state, pitching for any independent team that would hire him, and there were several. Among them were teams representing the towns of Coalinga, Lemoore, Visalia, Hanford, Tulare, and Whittier.

In February 1911, Jones pitched two games for the Doyles, a semipro team in Los Angeles, against the visiting Chicago Giants, a leading Negro team. Each game was a pitchers’ duel, Jones versus the Giants’ ace, Cyclone Joe Williams. The Giants won the first contest, 3-1, on February 2, and the Doyles won the second, 2-0, on February 19.40

In 1911 and 1912, Jones pitched for Lemoore and Hanford in the independent San Joaquin Valley League. Games were played only on Sundays. He devoted most of his time to his Lemoore pool hall and cigar store in 1911 and to his 40-acre farm near Lemoore in 1912.41 After his ban from professional baseball was lifted in late 1912, he launched a comeback.

In 1913, the California State League was a modest four-team circuit now affiliated with professional baseball. Jones pitched for the pennant-winning Stockton team and showed his old-time form. His 24-8 record included a streak of 14 consecutive victories from May 4 to July 16.42 His 8-3 triumph over Watsonville on September 5 was a special thrill for him. He was a weak hitter, but on this day, he slammed the first home run of his 14-year career.43

Jones pitched in 1914 for Vancouver, Portland, and Tacoma in the Northwestern League. He returned to California and pitched for semipro teams in Fresno and Turlock in 1915 and a Santa Barbara team in 1916 and 1917.

He divorced Margaret in 1918.44

In 1919, Jones had a tire-repair business in El Centro, California and pitched for a team there.45 He moved to Los Angeles about 1921, and there he continued his tire-repair work. In 1924 he pitched in an old-timers’ game and the Los Angeles Record remarked that no pitcher had ever duplicated his distinctive delivery.46

Jones married Charlotte Alice Lowe in Los Angeles in 1921. They moved to Fort Worth, Texas, in 1928,47 and US Census records indicate that they lived on a farm there in 1930 and 1940. Both died in Fort Worth: Charlotte in 1946 and Oscar on March 16, 1953. He was 73. The cause of death was a cerebral hemorrhage.48 His obituary mentions no children, only his sister Olive and a nephew.49 Oscar and Charlotte were interred at the Mount Olivet Cemetery in Fort Worth.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Howard Rosenberg and fact-checked by Terry Bohn.

Sources

Ancestry.com, Baseball-Reference.com, and Retrosheet.org, accessed December 2024.

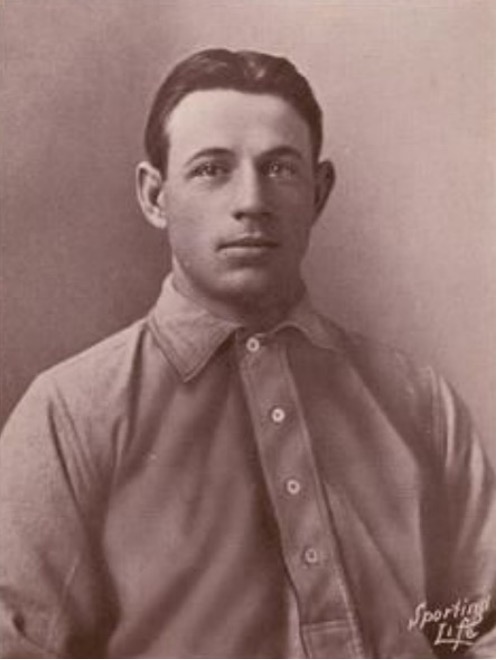

Image: 1903 portrait of Oscar Jones by photographer Carl J. Horner.

Notes

1 “New Superbas Need Introduction to Fans,” Brooklyn Eagle, April 12, 1903: 7.

2 Due to incomplete records, the exact number of Jones’s career victories is unknown.

3 “He’s an Athlete from the Ground Up,” Los Angeles Record, January 1, 1904: 5. Jones was nicknamed “Flip-Flap” and “Flip-Flop” for a particular gymnastic stunt he performed of that name. It is a “back handspring” in which a gymnast flips backward onto his hands and then continues backward onto his feet.

4 “City and County in Brief,” Arizona Republican (Phoenix), February 18, 1897: 5; Tombstone (Arizona) Epitaph, July 17, 1898: 2.

5 “He’s an Athlete from the Ground Up.”

6 “Personal,” Pomona (California) Progress, March 28, 1900: 3.

7 “Great Falls Wins the First of the Championship Games,” Great Falls (Montana) Tribune, September 29, 1900: 10; “Two for Helena,” Great Falls Tribune, October 1, 1900: 4.

8 “Angered by Certainty of Defeat, Helena Rowdies Mob Burke,” Great Falls Tribune, October 5, 1900: 4.

9 “Great Falls Wins the Pennant,” Great Falls Tribune, October 6, 1900: 4.

10 “Victory for San Diegans,” San Francisco Call, March 4, 1901: 6.

11 “Oakland Defeats Los Angeles Team,” San Francisco Examiner, April 1, 1901: 7.

12 “Angels Win Uphill Fight,” Los Angeles Times, April 5, 1901: 13.

13 Forrest D. Lowry, “California Cullings,” Sporting Life, May 4, 1901: 13.

14 “Jones Pitched Good Baseball,” Los Angeles Express, July 13, 1901: 9.

15 Before the National League introduced the “foul strike” rule in 1901, batters could foul off unlimited pitches without penalty. Once the rule took effect, a foul ball counted as a strike, except when the batter already had two strikes. As a result, batters were cautious about fouling off Jones’s pitches.

16 “Kicking Hitter Is Householder,” San Francisco Call, May 27, 1901: 6.

17 “Loo Loos Locate Pitcher Whalen,” San Francisco Examiner, July 6, 1901: 7.

18 “Jones Proves a Great Enigma,” San Francisco Chronicle, July 15, 1901: 10.

19 “Notes of Yesterday’s Home Game,” Los Angeles Express, September 13, 1901: 7.

20 “Pitcher Oscar L. Jones Hands Out a Few Packages of Art,” San Francisco Examiner, August 25, 1901: 38.

21 “Baseball Tomorrow at North Ontario,” Pomona Progress, January 31, 1902: 1.

22 “Jones Had a Merry Day at the Reds’ Expense,” Brooklyn Citizen, June 11, 1903: 5.

23 “Umpires Too Strict in National League,” Brooklyn Eagle, June 22, 1903: 8.

24 “Looping the Loop,” Brooklyn Standard Union, May 22, 1903: 9.

25 “Brooklyn Easily Defeats Cardinals,” St. Louis Republic, July 19, 1903: 7.

26 “Pitcher Oscar Jones Returns from National League,” Grass Valley (California) Union, October 14, 1904: 7.

27 “Stars from the Pinwheel of Fame, Sent Forth by ‘Ned’ Hanlon’s Superbas,” Brooklyn Eagle, April 3, 1905: 6.

28 “Jones Wants a Change,” Los Angeles Express, July 11, 1905: 10; “Jones Anxious to Join Reds,” Pittsburgh Press, July 26, 1905: 12.

29 Waldemar Young, “San Francisco Wins First Game 6 to 0,” San Francisco Examiner, April 7, 1907: Sporting Section, 3.

30 “Baseball Notes,” San Francisco Call, October 20, 1907: 49.

31 “Seals to Return Home Next Friday,” San Francisco Bulletin, March 31, 1908: 7.

32 Harry B. Smith, “First Game of the Season Is Won by Seals,” San Francisco Call, April 5, 1908: Sporting Section, 1.

33 “Jones and Curtis Go to State League,” San Francisco Examiner, March 16, 1909: 11.

34 1910 US Census.

35 “No State League Grounds in This City,” San Francisco Examiner, January 30, 1909: 8.

36 San Francisco Chronicle, January 30, 1909: 9.

37 Jones’s record in the 1909 California League was computed by the author from box scores found at Newspapers.com in December 2024.

38 “When Your Goat Is Got,” Stockton (California) Record, August 18, 1909: 4.

39 “Has Easy Delivery,” Los Angeles Times, March 5, 1911: VII-10.

40 “Giants Annex Lucky Victory,” Los Angeles Times, February 3, 1911: III-2; “Giants Win and Lose,” Los Angeles Times, February 20, 1911: I-6.

41 “Wins a Prize,” Lemoore (California) Republican, June 23, 1911: 7; “Personal Mention,” Hanford (California) Journal, February 5, 1912: 4.

42 Determined by the author from box scores found at Newspapers.com in December 2024.

43 “Producers Made It Three Straight,” Stockton (California) Mail, September 6, 1913: 10.

44 “New Suits, Filings, Etc.,” San Francisco Recorder, June 11, 1918: 8.

45 Advertisement for the Hart and Jones tire-repair business in El Centro in this: Imperial Valley Press, October 28, 1919: 4; and El Centro baseball game account in: Imperial Valley Press, December 15, 1919: 4.

46 “Old Timers Have Not Changed,” Los Angeles Record, July 2, 1924: 15.

47 “Oscar L. Jones,” Fort Worth (Texas) Star-Telegram, March 17, 1953: 7.

48 Texas death certificate.

49 Fort Worth Star-Telegram, March 18, 1953: 23.

Full Name

Oscar Lafayette Jones

Born

October 22, 1879 at Carter County, MO (USA)

Died

March 16, 1953 at Fort Worth, TX (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.