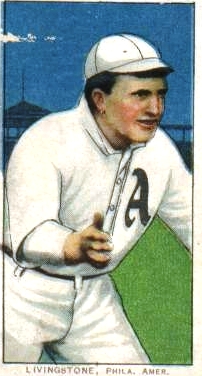

Paddy Livingston

Patrick Joseph Livingston was no Bill Dickey, and he was not even close to Roger Bresnahan, or any other catchers during the Dead Ball Era; but he made his mark on baseball. When he died on September 19, 1977, of an aneurism at the age of 97, he was the oldest former major leaguer at the time, and the last surviving player from the American League’s inaugural season of 1901.

Patrick Joseph Livingston was no Bill Dickey, and he was not even close to Roger Bresnahan, or any other catchers during the Dead Ball Era; but he made his mark on baseball. When he died on September 19, 1977, of an aneurism at the age of 97, he was the oldest former major leaguer at the time, and the last surviving player from the American League’s inaugural season of 1901.

Livingston was born in Cleveland on the near West Side in an Irish neighborhood, on January 14, 1880. He was married in 1902 and he loved his wife and their sons, and this to a large degree might have hurt his baseball career. His wife, Kitty, died in 1959. Both Paddy and Kitty were sincere Catholics and attended Mass nearly every day while in Cleveland.

Livingston spent seven seasons in the major leagues with Cleveland, Cincinnati, the Philadelphia Athletics, and the St. Louis Cardinals. He appeared in 206 games, batting .209 with 45 runs batted in, scoring 48 runs with no home runs. In the field he had a fielding percentage of .969.

His rookie season lasted one game with Cleveland in 1901, the first year of the American League. The Indians had taken Livingston after he did fairly well with a semipro team in Kent, Ohio. But after Livingston appeared in a game against Boston, he was released. Manager Jimmy McAleer didn’t think much of him. Livingston batted against Boston’s Cy Young and, as he put it, Young hit him in the ribs with a fastball. The resulting bruise was a souvenir of his big-league stay. When he returned home his father decided he was done with the big leagues, even though McAleer wanted to send him to the Athletics.

Paddy was then out of baseball until 1905, when he caught on with the Wheeling team in the Central League. He hit .312 and caught 83 games. He always compared what money he could make in the majors, against what he could do at home. It was how he lived his life. Home was important to him.

In that same year the New York Highlanders acquired Livingston’s contract, but contractual issues kept him from reporting. New York told him that they wanted to see how he did in Wheeling. Paddy would get only $150 despite his good year. Paddy later said, “They didn’t even send me a railway ticket! So I stayed in Wheeling.”

In 1906 he was drafted by the Cincinnati Reds. He would rather have gone to a Triple-A team, but the Reds needed him. Livingston didn’t impress the Reds, hitting only .158 and batting in only 8 runs, so he went to Indianapolis for the 1907 and 1908 seasons.

After Indianapolis it looked as though Livingston was ready for another turn in the major leagues but there was a problem. He had caught every game pitched by Rube Marquard in 1908. Marquard pitched 367 innings in 47 games with a 28-19 won-loss record. The Giants bought Rube’s contract for $11,000, the highest purchase price paid by a ballclub for a rookie at that time. Paddy said, “The Giants wanted me too, but Indianapolis demanded the same amount for me that it got for Marquard, and the Giants wouldn’t pay it. I was held back.”

Livingston performed another feat that year. The Indians had a pitcher named Louie Durham. He had been let go by Louisville but under Livingston’s guidance he did well, pitching complete games and winning five doubleheaders with Paddy catching them all. Durham went to the Giants in 1909 but didn’t make the team.

From 1909 through 1911, Paddy was with the Philadelphia Athletics and played on two world’s champions. In reminiscing about his days with Philadelphia, he said the players never cursed. That could have been because of A’s manager Connie Mack, but while Mack oversaw a great Athletics team, he was still on top of his game when it came to money. Today he would probably be called a tightwad.

When Livingston’s contract was bought by the Athletics, the contract talks were short and sweet. Paddy said he wanted to get $800 in the big leagues, but Mack told him he would get what he was paid in Indianapolis, $400.

Livingston said Mack was a great manager who helped his players by building their confidence. He said the players didn’t help him much because they were concerned about their own jobs. One player who helped him early on was Billy Sullivan, of the White Sox. He concentrated on defense in his tips to Livingston, for no wonder; Sullivan hit only .213 in his big-league career. You need to save your arm, Sullivan told him, but Paddy didn’t pay much attention to that advice, and many seasons he had a sore arm.

He would often tell Eddie Collins or Jack Barry to stand on second base, and he would chuck the ball to them. Paddy said he improved his aim by that means, but in the end his career was cut short by arm problems and his failure to hit.

During his days with the Athletics Livingston caught the deliveries of Chief Bender, Eddie Plank, Jack Coombs, and Cy Morgan. He handled Morgan’s deliveries more than any other catcher. For some reason Morgan could not win when Ira Thomas was behind the plate. Paddy suggested to Mack that he might have success with Morgan. He succeeded in making Morgan a winner, but at a cost.

Morgan threw a spitball and many times Livingston would have to stop the ball with his bare hand or his whole body. That is why his throwing hand was bent and twisted and his fingers showed signs of being dislocated.

One of Livingston’s memories was being on an American League all-star team that played a game at Cleveland’s League Park for the benefit of Addie Joss’s widow. Of Joss’s fastball, Paddy recalled, “He had a sweeping backswing on his delivery … and you could hardly see the pitch coming.” One day Joss hit him in the head. Paddy said he turned away just before he was hit. Livingston told interviewer Gene Murdock, “I didn’t want to show I was hurt so I ran to first base.” The first baseman was George Stovall, who promptly rubbed Paddy’s legs. Stovall said, “You can’t hurt wood, Paddy.”

In 1912 Harry Davis became the Indians manager and he wanted Livingston to join him. It looked like a good fit; Livingston could be at home and play ball. But it didn’t work out. After 20 games, Paddy got a sore arm. The treatment did not work out and he was released.

After a good year in Indianapolis in 1914, Paddy held out for more money in 1915 and wound up spending the season at home. In 1916 he was sold to Sioux City of the Western League. He hit .300 and caught just over 100 games.

But Livingston’s days as a Cardinal were short; he caught seven games and then was traded to the Milwaukee Brewers to assume managerial duties, while the Cardinals got a pitcher they wanted in return. Paddy didn’t want to go to Milwaukee, but after meeting with Cardinals general manager Branch Rickey and the Brewers at his home, he relented. The seven games caught for the Cardinals were the last in Livingston’s major-league playing career.

Salary was a problem in Milwaukee, and once when the Brewers were in Kansas City, the owner of the Sioux City club visited and asked Paddy to join the club the next year with a hefty salary increase. Paddy agreed, but the owner died in the offseason and the agreement died with him.

Paddy was out of baseball in 1918, but in 1919 he returned to the Athletics as a bullpen catcher. After the 1919 season, Livingston got a job with the Bridge Department in Cleveland. As he put it, “My baseball days were about over, I was 40, and I could be with my family. I stayed with the Bridge Department for 43 years until I was 83, retiring in 1963.”

During his career, he had good luck against Walter Johnson, getting a game-winning hit, but Paddy admitted that he had swung blind and got a lucky line drive hit. Against Ty Cobb he had success by throwing him out at second base twice. Despite only a .200 batting average, he had what he considered a satisfying baseball career in the major leagues.

As for modern players, he didn’t criticize their high salaries, saying they deserve what they could get from owners. And finally, he believed to his dying day that the spitball should be allowed to come back to the majors, despite the problems he had with the pitch.

Livingston died in Cleveland on September 19, 1977. He was 97 years old.

Sources

Personal notes from SABR researchers Gene Murdock and Fred Schuld

Mansch, Larry D. Rube Marquard—The Life and Times of a Baseball Hall of Famer. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 1999.

Livingston’s Baseball Hall of Fame File

Full Name

Patrick Joseph Livingston

Born

January 14, 1880 at Cleveland, OH (USA)

Died

September 19, 1977 at Cleveland, OH (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.