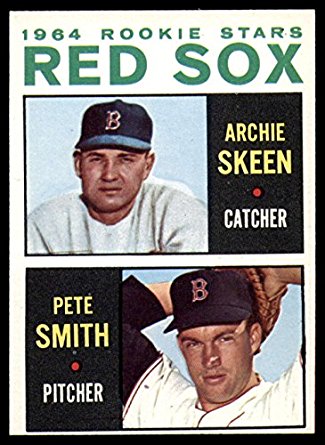

Pete Smith

On the very last ball he fielded as a major-league ballplayer, Pete Smith initiated a triple play. It happened in the seventh inning of the Red Sox game against the visiting Los Angeles Angels on September 28, 1963. It was a Saturday afternoon game at Fenway Park. There weren’t many fans in attendance – official data reports 2,282.1 The game was inconsequential in the standings. Boston was in seventh place, the Angels were in ninth place, and it was the next-to-last game of the season, near enough to the end that neither a win nor a loss was going to affect their ranking.

On the very last ball he fielded as a major-league ballplayer, Pete Smith initiated a triple play. It happened in the seventh inning of the Red Sox game against the visiting Los Angeles Angels on September 28, 1963. It was a Saturday afternoon game at Fenway Park. There weren’t many fans in attendance – official data reports 2,282.1 The game was inconsequential in the standings. Boston was in seventh place, the Angels were in ninth place, and it was the next-to-last game of the season, near enough to the end that neither a win nor a loss was going to affect their ranking.

Through six innings, the Angels held a 3-2 lead, the three runs charged to Red Sox starter Bill Monbouquette. Bob Heffner pitched a scoreless sixth for the Sox. After removing Heffner for a pinch-hitter in the bottom of that inning, manager Johnny Pesky called on Smith to take over in the top of the seventh.

Smith, a right-hander who had appeared in six prior big-league games, gave up a double to the leadoff batter, first baseman Charlie Dees. He then walked right fielder Lee Thomas. The Angels had runners on first and second with nobody out. Third baseman Felix Torres stepped into the batter’s box. He attempted a sacrifice bunt to advance both baserunners, but popped up the ball, described by the Boston Globe as “40 feet toward the mound.”2 But before Smith could catch it, Red Sox shortstop Eddie Bressoud shouted out, “Let it drop!”

After the game, Bressoud said, “I guess several of us called when we saw that Torres didn’t break. Pete never hesitated.”3

He didn’t hesitate, perhaps, because it was a play he’d anticipated. “I thought of a triple play,” he said after the game. “I’d always dreamed of making a play like that.”4 He needed a little help, though. “As I went for the ball to field it, I couldn’t watch the runners to see if they were running or holding up. So I went for the ball. Ed Bressoud called to me to let it drop. So I did. And we got the triple play.”5

The play “took the moxie out of the Angels,” wrote the Boston Record American’s Larry Claflin, Smith had “turned an L.A. sacrifice attempt into mass murder.”6

Both runners had assumed Smith would catch it and neither broke for the next base. Torres himself hadn’t started running to first. Smith let the ball drop, picked it up, and fired to Frank Malzone at third base. Malzone threw to Bressoud covering second, and Bressoud threw to Felix Mantilla who came over from second base to cover first. “None of the Angels on the basepaths moved a step. The same was true of Torres, who never left home plate.”7 It was a 1-5-6-4 triple play. Three outs, side retired, no runs.

The Red Sox didn’t score in the bottom of the seventh. Smith pitched the eighth, and retired all three men he faced on a groundout to short, groundout to second, and a strikeout.

In the bottom of the eighth, Boston’s Lou Clinton singled. Malzone advanced him to second base with a successful bunt. Bressoud then doubled to right-center and scored Clinton to tie the game. Russ Nixon then grounded, second base to first, for the second out, and Smith was pulled for Dick Williams (later a Hall of Fame manager) who grounded out unassisted to first base.

The Red Sox won the game. Dick Radatz got the Angels to go down, with just a single, in the top of the ninth. In the bottom of the ninth, Gary Geiger and Mantilla walked. Carl Yastrzemski sacrificed (with another successful bunt) to move the runners to second and third. Dick Stuart was walked intentionally and Clinton won the game with a ball hit hard off the center-field wall. As the pitcher of record, Radatz took the win. He finished the season with a record of 15-6, astonishing for a relief pitcher. He had a 1.97 ERA.

It was, for Smith, his last major-league game. The last pitch he threw was strike three to Bob Perry, closing out the top of the eighth. He hadn’t fielded a ball in the eighth; the last ball he fielded was the ball he threw to Malzone to start a triple play.

There have been those in baseball who have hit a home run in their last at-bat in the big leagues, most notably perhaps Ted Williams. As far as we know, Pete Smith is the only fielder – pitcher or otherwise – who initiated a triple play with the last ball he fielded.

Smith, in his career, had an unblemished fielding record in the major leagues. He handled five chances, the assist on the triple play being one of them.

He had indeed only played in the seven games, one in 1962 and six in 1963. But he was a major leaguer.

Pete Smith came from Natick, Massachusetts. He was born Peter Luke Smith on March 19, 1940, in the Greater Boston suburb to Donald and Lillian Smith. Donald Smith worked for Dennison Manufacturing, a box manufacturer, in Framingham for 25 years or so. He headed up a division for the company.

Foreshadowing his career in professional baseball, Pete pitched in the first game of Natick Little League history – and threw a no-hitter. He was the offense, too, getting the first hit of the game (and, thus, the league) and scored the only run in the 1-0 game.8

In his sophomore year, Smith threw a no-hitter for Natick High in May 1955. Several other outstanding performances led to him being voted team MVP. His brother Terry played on the team as well. The family moved to Chicago for a year for Donald Smith’s work – Pete’s junior year of high school – but were back in time for Pete to help lead Natick to an undefeated season as Class-B basketball champions of Eastern Massachusetts in the winter of 1956-57. Pete was team and league MVP and also selected All Tech Tourney first team. This 1957 basketball team was part of the Natick Athletic Hall of Fame’s initial inductee class in 2010. In the fall of ‘56 he was the star quarterback on the football team. He was named student athlete at Natick in 1957. Smith also excelled academically, a member of the National Honor Society.9 He was accepted to Harvard but chose Colgate, which offered a better financial deal. Pete also was accepted to Harvard’s MAT (master’s in teaching) program in 1961 but chose to play minor-league baseball in the Boston Red Sox organization.

Smith attended Colgate, as did his batterymate from Natick High, Joe Wignot, and another Natick pitcher, Dave Connell.10 Natick coach Joe Hoague was a Colgate graduate. The summer before Colgate, Smith broke his leg so he was unable to play football and realized he wasn’t good enough for their basketball team. He concentrated on baseball. He was 5-0 as a freshman, then joined the varsity, at one point, striking out 23 Bucknell batters in a game. His varsity record for Colgate was 20-5. He was named student athlete at Colgate in 1961. In June 1961, the month he graduated from Colgate, he signed with the Red Sox.11

Harry Dorish tried to see Smith pitch, but three of the four times he went, the games were rained out. Finally, Smith later said, “I finally made it by showing up for a workout at Fenway Park in June. I worked batting practice, hit a few myself and was signed up by Neil Mahoney.”12 Farm Director Mahoney is credited with the signing, though Rudy York looked him over and “immediately advised Mgr. Mike Higgins to sign him. Pitching coach Sal Maglie liked him.”13

A right-hander, Smith was listed as 6-feet-2 and 190 pounds.

Smith didn’t spend much time in the minors. After signing, for a reported $16,500 bonus, he was initially assigned to the Class-D Alpine Cowboys, in the Sophomore League at Alpine, Texas.14 There he was 4-6 (3.68). He earned a promotion to the Johnstown (Pennsylvania) Red Sox in the Class-A Eastern League and in five games was 4-1 but with a discouraging 5.28 earned run average.

Over the winter, he pursued graduate studies at the University of Southern California and earned a master’s degree in education.

He joined the Red Sox in Scottsdale for spring training in 1962 and, along with Don Schwall, caught the eye of Sal Maglie. “This boy seems the most matured of the younger group,” said Maglie. “He’s smart. He learns fast.”15 On March 22, the Red Sox assigned him to the Seattle Rainiers, managed in 1961 and 1962 by Johnny Pesky. The Pacific Coast League’s Rainiers were then the top club in Boston’s minor-league system. Billy MacLeod, a pitcher from Gloucester, was with Seattle, too, as was Dave Morehead.

Smith pitched out the season in the Coast League, with a 3.09 ERA and a record of 10-12; Seattle finished in fourth place. He struck out 82 but walked 69 batters. He threw seven complete games, four of them shutouts.

Smith made his major-league debut, starting in Detroit on September 13, and it was a rough one. He got through the first inning 1-2-3, but Rocky Colavito led off the bottom of the second and homered. Smith retired the next three. In the third inning, he gave up two singles and a run-scoring sacrifice fly, followed by a walk and a three-run homer hit by Al Kaline. In the bottom of the fourth, Smith gave up another three-run homer to Chico Fernandez. It was 8-0 Tigers, and Higgins brought in Billy MacLeod to secure the final out of the fourth. It was Pete Smith’s only appearance of 1962, 3 2/3 innings, a 14-6 loss, and a 19.64 ERA to ponder over the winter months.

During those months, Smith was in the United States Army for a six-month stint. He had a low draft number and the Red Sox helped him get into an Army Reserve unit. He served at Fort Dix and then, with an MOS of military intelligence, served at Fort Meade, Maryland. He was in the active reserve for about a year after serving 4 1/2 years in a control group out of St. Louis.

He joined the Sox in Scottsdale about a week late, in early March. Later that month, he was sent to Seattle again. Mel Parnell was the manager, Pesky having been promoted to become manager in Boston. The Rainiers finished in last place, 30 games out of first. Smith won his first start, a 2-0 shutout. He finished with a record of 12-14, with a 4.61 ERA. He improved his strikeout to walks ratio, with 155 Ks to 77 BBs. Smith was the only player from the Sox minor-league system asked to join the Boston ballclub in September. When the Red Sox visited Los Angeles on a road trip in the first half of the month, he joined the team.

His first appearance for the 1963 Red Sox was on September 15 in Kansas City. He started the game and pitched six innings, giving up three runs on a walk and four singles. The Red Sox won the game, 5-3, but with two runs in the top of the ninth giving Jack Lamabe the victory. Manager Pesky was pleased enough, saying of Smith, “I managed Pete last year in Seattle. He is 50 percent better now than he was a year ago.”16

On September 18, Smith pitched a hitless inning of relief in Chicago. He pitched in four more games, all at Fenway Park, the last two of them being scoreless outings, as he progressively brought down his ERA to 3.60 over the course of 15 innings in six September games. Of course, kicking off a triple play in his final game spared him the possibility of a run crossing the plate.

He signed his contract for 1964 but turned up to spring training with something of a sore arm. He pitched for a while, but was once again assigned to Seattle on March 22. On April 7, the Rainiers sent him to Ocala for possible reassignment. It was reported that he had suffered a shoulder separation which may have dated back to a scrub football game in the fall of 1963.17 Smith himself is not sure where the injury occurred but recalls hurting his arm throwing curveballs in the USC batting cage in January 1964.18 He spent almost the entire year on the disabled list. In late September, Smith and several others were sold outright to Seattle, to make room on the Red Sox roster for upcoming rookies, one of whom was Jim Lonborg.

He signed with the Pittsfield Red Sox (of the Double-A Eastern League) for 1965, starting two games and working a total of six innings. He was 0-1 with a 3.00 ERA. They were his final six innings in professional baseball. “I had a calcium deposit in my arm,” he says. “They probably could fix it today. I could do everything but throw a fastball hard. That’s when it would hurt me. I could play tennis, but as soon as I tried to throw that fastball, there was excruciating pain. My last inning was against Elmira. Earl Weaver was the manager and in that inning I faced Mark Belanger – who was from Pittsfield – and Lou Piniella. One inning and then I was done.”19

By the autumn, he was teaching math and coaching at Kimball Union Academy. From there he went to Berwick Academy, again to teach math (and serve as head baseball coach). After that it was out to California for another position for a year or two, and then to Natick High School for 5 1/2 years as a guidance counselor.

In 1971, Smith worked for a year as baseball coach at Beaver Country Day School.20 His longest-standing position followed next, working as a guidance and placement counselor at a vocational school, Putnam-Northern Westchester BOCES in New York, a position in which he served for 27 years. There he coached some golf and tennis.

Pete Smith married in 1976, and remains married to his wife Arlene. With a master’s in nursing, Arlene Smith worked as a registered nurse. Their daughter Kellyn was born in 1977. Kellyn Smith Kenny is Vice President of Marketing for Uber.

Both Pete and Arlene retired early, and moved to The Villages, Florida, at the end of 2002. “This place is paradise for me,” Smith enthuses. “It’s like an adult Disney World. They’ve got so many activities going on…and we’ve got the largest Red Sox Nation club in the country. There’s so many things to do, I meet myself doing things!”21

He keeps active, with golf about four times a week, tennis a couple of times, and even slow-pitch softball twice a week. The question was called for: “When you play softball, do you pitch?” Pete’s response: “You know, I usually don’t but I pitched yesterday and we ended up winning. Pitching slow-pitch softball is difficult. I did enjoy it; when you pitch, you’re in the game. We play six-foot to 12-foot arc. You’ve got to put it on the plate.”

Joking, he was told, “Well, you’ve got to pull off another triple play sometime.” “You know what? Technically, we should have had one yesterday. They had the bases loaded. The outfielder caught a fly ball. The guy on third was tagging up and he scored. I cut the ball off. The guy on second went off a little too far. We doubled him off. The guy on third – he hit the wrong home plate. We have two plates. He hit the home plate where the pitch goes – but we have another plate which is about 15 feet away, so there won’t be any collisions. He hit the wrong plate. A guy hits the wrong base, he’s automatically out. It would have been a triple play but the umpire didn’t see him. Our catcher said, ‘Hey, he hit the wrong plate,’ but the umpire didn’t see it. He was probably watching the play at second.”22

Smith keeps in touch with Bill MacLeod, Dave Morehead, and a couple others from his time. In 2012, Smith was one of over 200 Red Sox alumni who took up the team on their offer to come to Fenway Park and be part of the celebrations of the ballpark’s 100th anniversary. “It was first class all the way,” he said. Pete and Arlene flew to Boston from Florida. “I had been to other Red Sox reunions, but nothing like this one. We had a police escort to the park. We were all introduced. I was the 165th player they announced…The picture of me [on the video screens] was when I was 22. I then took my position on the field.”

A couple of days beforehand, he had shot his age – 72 – at golf, and days after the 100th anniversary party, he and Doug Flutie were inducted into the sports hall of fame at Natick High School.23 Some 25 years earlier, he was inducted into the Colgate Athletic Hall of Fame, primarily for baseball but he had also lettered in cross country and in soccer. In his junior year he was the starting goalie in an NCAA quarter-final 3-2 overtime loss to Bridgeport. That same year he pitched at Cooperstown against Delaware in a regional NCAA game that Colgate lost.

Last revised: July 7, 2017

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Phil Williams and fact-checked by Kevin Larkin.

Sources

Thanks to Pete Smith for a telephone interview on February 26, 2017. Much of the family information comes from that interview.

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed Smith’s player file from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, Rod Nelson of SABR’s Scouts Committee, and the SABR Minor Leagues Database, accessed online at Baseball-Reference.com.

Notes

1 There were apparently quite a few attending the game as unpaid guests. The Boston Globe reported 5,301 with 2,282 paid. See Roger Birtwell, “Sox Chalk Up Triple Play, Win Too,” Boston Globe, September 29, 1963: 29. The McKenna article in the Boston Herald reported the same attendance figures.

2 Roger Birtwell.

3 Henry McKenna, “Sox Scored, 4-3, On Clinton Hit,” Boston Herald, September 29, 1963: 214.

4 “Dream Fulfilled for Sox’ Smith,” Boston Globe, September 29, 1963: 84.

5 Ibid.

6 Larry Claflin, “Sox Share Angels, 4-3,” Boston Record American, September 29, 1963: 24.

7 Ibid. The Associated Press account of the triple play erred in reporting Heffner as the Red Sox pitcher.

8 Pete Smith, email to author, February 28, 2017.

9 Ralph Wheeler, “Smith Back as Pitcher for Natick,” Boston Herald, April 18, 1957, 34. Donald Smith remained in Chicago and ran their distributing facility there. Terry became an English teacher and a football coach at Croton-Harmon High School in New York.

10 Ralph Wheeler, “Melrose Winner, 11-0,” Boston Herald, April 24, 1960: 216.

11 Warren Walworth, “Sox Get Guindon With 135G Bonus,” Boston American, June 10, 1961: 6.

12 Fred Foye, “Natick’s Pete Smith Still Eyes Sox Job,” Boston Traveler, March 19, 1962: 18.

13 D. Leo Monahan, “Sox Coaches High on Natick Hurler,” Boston Record, June 12, 1960: 50.

14 Ibid.

15 John Gillooly, “Maglie Sees Schwall Repeating ‘61 Form,” Boston Record American, March 5, 1962: 11.

16 Bill Liston, “Smith Seen Ready for Majors,” Boston Traveler, September 16, 1963: 25.

17 Hy Zimmerman, “Edo’s Mound Problems Gain as Sore-Armed Hurlers Leave,” Seattle Daily Times, April 7, 1964: 28. The other sore-armed hurler was Dave Busby.

18 Pete Smith, email to author, February 28, 2017.

19 Author interview with Pete Smith, February 26, 2017.

20 “The Sports Log,” Boston Globe, March 23, 1971: 28.

21 Author interview.

22 Ibid.

23 Earl Watson, “Villages Resident and Ex-Boston Red Sox Player Pete Smith Attends Fenway Park Birthday Bash,” Orlando Sentinel, May 13, 2012.

Full Name

Peter Luke Smith

Born

March 19, 1940 at Natick, MA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.