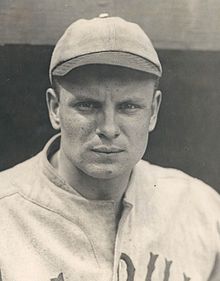

Pickles Dillhoefer

The Philadelphia Phillies have a long history of trading away future Hall of Famers for lesser players. In 1982 they swapped a young Ryne Sandberg and veteran Larry Bowa for Ivan DeJesus. In the 1960s they sent 23-year-old Fergie Jenkins to the Chicago Cubs for two pitchers with a combined age of 72. The very first trade they made of this nature occurred in December 1917. They sent Grover Cleveland Alexander and catcher Bill Killefer to the Cubs for pitcher Mike Prendergast, catcher Pickles Dillhoefer and $55,000. Prendergast finished his career winning 13 games for Philadelphia. Alexander had 173 wins left in his arm. Because of World War I, Dillhoefer played a mere eight games before entering the service. The Phillies traded him to St. Louis for the 1919 season.

The Philadelphia Phillies have a long history of trading away future Hall of Famers for lesser players. In 1982 they swapped a young Ryne Sandberg and veteran Larry Bowa for Ivan DeJesus. In the 1960s they sent 23-year-old Fergie Jenkins to the Chicago Cubs for two pitchers with a combined age of 72. The very first trade they made of this nature occurred in December 1917. They sent Grover Cleveland Alexander and catcher Bill Killefer to the Cubs for pitcher Mike Prendergast, catcher Pickles Dillhoefer and $55,000. Prendergast finished his career winning 13 games for Philadelphia. Alexander had 173 wins left in his arm. Because of World War I, Dillhoefer played a mere eight games before entering the service. The Phillies traded him to St. Louis for the 1919 season.

William Martin Dillhoefer was born in Cleveland on October 13, 1893, to William and Ottilia (aka Della) C. (Butter) Dillhoefer. He had two older brothers. His mother died in 1895 and the family moved in with his maternal grandparents. The elder Dillhoefer worked as a clerk or salesman over the years and died in 1907. In 1910 teenaged William and his brothers were living with his paternal aunt on the east side of Cleveland.

Coming from German Catholic lineage, Dillhoefer attended school at Villa Angela and then went to St. Ignatius High School, both in Cleveland. He learned his baseball in the schoolyards and sandlots. He started to draw attention for his catching but was comfortable anywhere on the diamond. In 1910 he played for the Zeitz Stars. In 1911-12 he played in the Industrial League, first for American Can (he batted .475)1 and then for Cleveland Twist Drills.

The Class A League (one step below the semipro City League) in Cleveland was touched with a scandal in 1913 when it was found that four players on the Strollers were ineligible. Dillhoefer was recruited as their new catcher in late July. The Strollers made the playoffs but were eliminated quickly. Dillhoefer’s performance in Cleveland earned him a place with the Portsmouth Cobblers in the Class D Ohio State League for 1914.

The nickname “Pickles” was hung on Dillhoefer while he was growing up in Cleveland. The combination of Dill and Pickle was too much for friends to avoid. He was most often called Pickles by scribes, who also used “Dilly.” On rare occasions the St. Louis Post-Dispatch called him “Doodle.”2

With Portsmouth Dillhoefer split time behind the plate with Red Munson and Nick Francisco. The league started with eight teams in three states but closed out with only four entries. Dillhoefer usually batted eighth and played in 97 games with a .226 batting average.

Dillhoefer returned to Portsmouth for the 1915 season and met 10 new teammates, including outfielder Austin McHenry. The Cobblers captured the first-half pennant easily. In September they defeated Maysville (second-half champ) in a playoff series, four games to one. Dillhoefer played in 103 games and batted .280 with four home runs. He balked at returning to Portsmouth for a third season, signing a contract at the last minute.

The Cobblers were nearly unstoppable in 1916. They ran away from the contenders by winning over 70 percent of their games. Dillhoefer was moved up to the number-five spot in the batting order. He responded with a .327 batting average before a smashed finger sidelined him.3 The league reorganized at midseason and started the second half with only four franchises. Dillhoeffer took over at second base and batted leadoff when he returned from his injury. After six games the league disbanded. McHenry and Dillhoefer were both sold to Milwaukee of the American Association.

Dilhoeffer debuted with Milwaukee on July 24, catching Jim Bluejacket in a loss to Minneapolis. The Brewers finished last, but Pickles continued his strong hitting by posting a .292 average in 50 games. He missed two weeks after getting a thumb smashed and returned to action just in time to learn that the Chicago Cubs had drafted him. President Weeghman of the Cubs called Dillhoefer “a coming star” and compared him favorably to the White Sox’ future Hall of Famer Ray Schalk.4

Reportedly scouts from every franchise had looked at Dillhoefer. He stood 5-feet-8-inches tall and weighed 155 pounds. He threw and batted right-handed. Those figures matched him well with Schalk and evoked the comparisons. Scouts were impressed with Dillhoefer’s throwing arm, his speed, and the energy and enthusiasm he exhibited.5 The Cubs trained at Pasadena, California, in 1917. Art Wilson was regarded as the number-one catcher, with Rowdy Elliott also returning. Dillhoefer had to compete with former University of Michigan star Leland Benton for the third spot.

Dillhoefer saw plenty of action once the exhibition games began. On March 7 he was forced to the bench by a wrist injury. He had injured it in 1916 and then aggravated it over the winter when cranking an automobile. When he fell awkwardly during action, he jammed it but did not break any bones.6 Doctors thought he would need to sit out a week or two. Dillhoefer had other ideas and was in the lineup four days later. He smacked a home run to beat the Los Angeles Angels 7-5.

Dillhoefer made the Cubs’ Opening Day roster and debuted as a pinch-hitter on April 16. He was used May 3 to rest Art Wilson, then he was sold to Joe Tinker’s Columbus, Ohio, team in the American Association. On July 3 the Cubs sent Earl Blackburn to Columbus for Dillhoefer. Pickles had been on fire in the minors. The wire services reported that he batted .425 in his first 13 games. His average had dropped to .296 by the time he left the team.

Dillhoefer was installed as the regular catcher on July 10 in Brooklyn. He played 23 games in the next month, but his hitting was nonexistent. When his average reached .159 on August 11, he was benched. He closed out the season batting a lowly .126.

The Alexander deal with the Phillies gave Dillhoefer new surroundings. He reported to training camp in St. Petersburg, Florida, without having signed a contract. At least Dillhoefer reported, Cy Williams, Milt Stock, Chief Bender, and others were early no-shows as they dickered over contract terms. While in Florida, Dillhoefer received a notice that he had been classified A1 for the military draft. It was only a matter of time before he would be called to duty.

The Phillies broke camp with Dillhoefer on the roster. He played in eight games in April and May before Uncle Sam beckoned. He had made one hit for the Phils, on May 18 against Claude Hendrix of the Cubs.

Rather than wait for the draft, Dillhoefer choose to enlist, along with teammate George Whitted. (Yes, Philadelphia had both Pickles and Possum on their roster!) He felt being drafted sent the message that he did not want to serve, and said, “I am happy to say I did not take a job in a munitions factory or a shipyard or something that would make me exempt. I want to do my bit and the sooner the better.”7 He went through basic training and then was assigned to the quartermaster unit at Camp Merritt in New Jersey. He rose to the rank of corporal in September and to sergeant in November. He valued his service to the nation and became a member of the American Legion after his discharge.

In January 1919 the Phillies sent Milt Stock, Dixie Davis, and Dillhoefer to the St. Louis Cardinals for Doug Baird, Gene Packard, and Stuffy Stewart. Dillhoefer joined Verne Clemons and Frank Snyder as the Cardinals’ catching corps. He batted better than Snyder (.213 to .182). Statistically his fielding was the weakest of the trio, but statistics did not seem to matter to the Cardinals fans. He became one of their most popular players because of his “fighting spirit, boundless enthusiasm and excellent base-line coaching.”8

In 1920 the Cardinals went with just Clemons and Dillhoefer. Pickles saw action in 76 games and posted his best major-league statistics in runs, hits, doubles, batting, slugging, and on-base percentage.

The most explosive game of his career was played on July 24, 1920, against the Boston Braves when he smacked four hits. With the game tied, 6-6, he opened the 10th with a triple. Boston loaded the bases intentionally and coaxed a popup, but then watched Jack Smith drive the ball to deep center for the St. Louis victory. Dillhoefer also combined with shortstop Doc Lavan on two strike-’em-out, throw-’em-out double plays.

Dillhoefer moved to St. Louis that winter and took a job as a Ford auto salesman. He was slow to sign with the Cardinals, but reported to Bogalusa, Louisiana, for the start of camp on time. Clemons would be the number-one catcher again in 1921 and the Cardinals would also carry Eddie Ainsmith. Dillhoefer’s hitting was an issue early on. He got two hits in his second start, but after nine more appearances his average was at .091. A three-hit game against Brooklyn on June 10 finally boosted him over the Mendoza line to .222. He closed out the year batting .241 in 76 games.

Dillhoefer’s feisty nature made headlines during the season. He drew a three-game suspension in June for a tirade aimed at umpire Bill Brennan. In August he got into a fistfight with Frank Snyder, now a Giant. Cardinals outfielder Joe Schultz had been beaned and Dillhoefer suggested retaliation would be coming. Snyder threw down his mask and attacked Dillhoefer. Despite giving away 30 pounds, Dillhoefer defended himself well until umpire Ernie Quigley stepped between them. Snyder was ejected.9

Milt Stock was one of Dilhoeffer’s best friends in baseball. He was visiting at Stock’s home in Mobile, Alabama, when he was introduced to a local schoolteacher named Massie Slocum. The pair hit it off immediately. They were married in a lavish ceremony in Mobile on January 14, 1922. They honeymooned in New Orleans before going to their home in St. Louis.

Tragically, Dillhoefer was found to have typhoid fever upon their return to St. Louis. This developed into pneumonia. The infection spread and affected his gall bladder. A surgery offered no relief and Dillhoefer died the morning of February 23 in St. John’s Hospital in St. Louis. He was 28 years old and had been married just under six weeks.

Massie Dillhoefer, accompanied by Pickles’ brother Edwin, returned the body to Mobile. A funeral was conducted with military honors provided by the local American Legion. His pallbearers included Branch Rickey, Milt Stock, and Verne Clemons. Dillhoefer was buried in Magnolia Cemetery. Massie returned to teaching and never remarried. She died on August 10, 1985, in a hospice facility in Daphne, Alabama. Her body was returned to Magnolia Cemetery, where after six decades she was again beside her beloved husband.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Len Levin and verified for accuracy by the BioProject fact-checking team.

Notes

1 “Dillhoefer Tops Hitters,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, October 29, 1911: 21.

2 “Pertica, Aided by Brilliant Support, Hurls Cardinals to Their First Victory at Home,” St Louis Post-Dispatch, May 1, 1921: 6. On Dillhoeffer’s Hall of Fame questionnaire his widow, Massie, listed both Pickles and Dilly as nicknames.

3 “Seven Champs in the .300 Class,” Portsmouth (Ohio) Daily Times, July 1, 1916: 2.

4 “Cubs Are Banking on ‘Pickles’ Dillhoefer,” Portsmouth Daily Times, November 18, 1916: 20.

5 “Sports Up to the Minute,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, November 21, 1916: 11.

6 “Cubs Are Walloped,” Moline (Illinois) Dispatch, March 8, 1917: 8.

7 “Two Phils Are Ready to Jump Team for the Army,” New Castle (Pennsylvania) Herald, May 14, 1918: 10.

8 “ ‘Pickles’ Dillhoefer, Cardinal Catcher, Dies,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, February 23, 1922: 1.

9 “Quigley Quells Incipient Riot,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, August 5, 1921: 12.

Full Name

William Martin Dillhoefer

Born

October 13, 1893 at Cleveland, OH (USA)

Died

February 23, 1922 at St. Louis, MO (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.