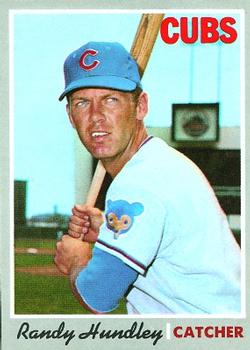

Randy Hundley

Despite having a lifetime .236 batting average, Randy Hundley is one of the most beloved Chicago Cubs of all time.

Despite having a lifetime .236 batting average, Randy Hundley is one of the most beloved Chicago Cubs of all time.

The Virginia native played 10 seasons with the Cubs in the 1960s and 1970s and was considered a leader on the field for the team that endured a historic collapse in 1969. Hundley also introduced the one-handed catching style, a technique that Hall of Famer Johnny Bench and other catchers soon copied. Upon retiring after the 1977 season and managing 3 1/2 years in the minor leagues, he established baseball fantasy camps for adults. To this day, he operates the Randy Hundley Fantasy Camp in January at the Cubs spring training complex in Mesa, Ariz.

Cecil Randolph Hundley Jr. was born on June 1, 1942, in Martinsville, Virginia, to Cecil Randolph Hundley Sr. and Lois Mitchell Hundley, with one brother, Kenn, and two sisters, Mary Lois and Pat. Hundley’s father owned and operated the Cecil R. Hundley Construction Company, Inc. for 40 years before retiring in 1984.1 His father, who taught his son how to catch one-handed, played semi-pro baseball for more than 20 years and was involved with baseball until about 1967–his last year as coach of the Connie Mack Martinsville Pirates.2

As a child, Randy played shortstop and pitched, but he eventually decided playing shortstop was too boring. And his father didn’t want him to pitch even though he “had this big curveball and would knock those hitters down and scare the pee out of them.”3

So when Randy told his dad one day he “needed to be where the action is,” his dad responded, “Son, I’m going to teach you to be a one-handed catcher.”4

After pointing a finger between Randy’s eyes, the elder Hundley said, “If I ever see you put that bare hand up to catch the ball, I’m going to come and personally take you out of the game.”5

As a result, Randy started catching one-handed in Little League, using his father’s mitt.6

Years later, his father observed, “That extra hand does nothing but get in the way. It’s easier to catch one-handed today anyway. The mitts are like a first baseman’s mitt and you can stretch for a bad pitch so much further with one hand, just like a first baseman does.”7

Randy’s athletic prowess was evident at John D. Bassett High School in Bassett, Virginia, where he played baseball for four years, basketball for two years, and football for two years. Named the “Most Athletic Boy” his senior year, he played guard on the state champion basketball team as a junior and was the starting quarterback on the football team before he decided to drop the sport his senior year.8

He and his high school sweetheart, Betty Foster, attended the Bassett High School prom in 1960 and were married on September 30, 1961, at the Tabernacle Baptist Church in Bassett, Virginia.9 Randy and Betty went on to have four children: Todd, who played in the major leagues for 15 years, Chad, Julie, and Renee.10

Randy started drawing the attention of professional baseball scouts between his sophomore and junior years of high school. One afternoon in the middle of February during his junior year, San Francisco Giant scout Tim Murchison came to see him at school.

“Well, you can just imagine what my heart did. He had just seen me play between my sophomore and junior year during the summer in American Legion ball. The scout had been looking at the older kids, and I happened to have a good series,” Randy said.11

In the spring of 1958, Randy and his father made an oral agreement in which his dad agreed to train Randy extensively and to serve as Randy’s coach, business agent, manager, publicity director, and sales agent in contract negotiations with professional baseball teams. In addition, Randy’s father Cecil was to receive 50 percent of any signing bonus. Later, Randy and his dad estimated Randy might get — at most — a $25,000 bonus, as bonuses had been limited to $4,000 before 1958.12

After graduating from high school in June 1960, Randy signed a contract with the Giants and received a $110,000 bonus payable over five years. Under the two-year-old oral agreement, Randy also was to receive not less than $1,000 a month during the baseball season because he and his father figured it might take him at least five years to get to the major leagues.13 The Cubs also had been watching him play in high school, but lost interest when they signed bonus baby Danny Murphy, a 17-year-old outfielder from Massachusetts.

Randy made his professional baseball debut with Salem in the Class D Appalachian League after turning 18. He spent the next two seasons with Fresno, the Giants’ Class C affiliate in the California League. Despite batting .239 with Fresno in 1962, he was promoted the next season to El Paso in the Double A Texas League where he hit .325 with 23 homers and 81 RBI as a 21-year-old. In the process, he helped El Paso set a Texas League record for most home runs by a team in one season.14 He also made the Texas League All-Star team and led the league’s catchers in fielding.

The Giants had a surplus of catchers at the time so Randy was optioned to the Minnesota Twins for one year. The Twins sent him to their International League team in Atlanta, Georgia, which lost 93 out of 148 games that season. Nevertheless, he made his major-league debut against the Cubs on September 27, 1964, at Wrigley Field as a pinch-runner for Duke Snider in the top of the seventh inning of the Giants’ 4-2 loss.

He split the 1965 season between Tacoma, the Giants’ Triple A affiliate in the Pacific Coast League, and San Francisco. When the Giants’ regular catcher Tom Haller was injured, Randy was inserted into the lineup and faced Los Angeles Dodger aces Sandy Koufax and Don Drysdale the first two nights.

“The first time I batted against Drysdale he threw right at my head,” Randy said. “I got up, dusted myself off and hit the next pitch foul down the left-field line. Believe me, I was proud of that foul.”15

Still, Giants’ manager Herman Franks frowned on Randy’s one-handed catching style, to which the latter replied, “My dad was a semi-pro catcher and he taught me to protect my hand that way.”16

After six years in the Giants’ organization, Randy gave the Giants an ultimatum: “Play me, replace me, or trade me.”17

On December 2, 1965, Randy and pitcher Bill Hands were traded to the Cubs for pitcher Lindy McDaniel and outfielder Don Landrum–one of the better trades in Cubs’ history.

When Leo “The Lip” Durocher took over the Cubs’ managerial duties in 1966, he claimed the Cubs weren’t an eighth-place team–their finish in 1965. Durocher was right! Even though the North Siders finished in tenth place in 1966, Randy had a banner rookie season, catching 149 games to set a National League record for most games caught by a rookie, leading NL catchers in assists and finishing third among catchers in homers.

On May 19, 1966, he doubled, tripled, and stole home in a 7-1 win over the Houston Astros. A month later, he hit his first major-league grand slam off of Drysdale. He also hit for the cycle in a 9-8 win over the Astros in 11 innings on August 11, 1966. He was named to the All-Star rookie team as a result of his accomplishments.

“We had a terrible year trying to learn how Leo wanted us to play the game,” Randy said.18

And, Randy recalled, “My first year, Leo drove me nuts. I thought, if this is major-league baseball, I don’t want it, I don’t need it, take this job and shove it.”19

But the Cubs’ fortunes started turning around in 1967 and their catcher played an instrumental role. The 25-year-old ex-Giant earned his first and only Gold Glove Award that season, establishing a major-league record for fewest errors by a catcher in 150 or more games and breaking the NL mark for fewest passed balls in 150 or more games. His skipper did an about face, telling Randy, “Randy, you’re my manager on the field and whatever you say goes.”20

Although he missed the first three games in ’67 due to injuries to his left knee and left ankle– both ailments suffered during the same play in spring training–he had caught every inning of every Cubs game since the fourth game of the season through June. In fact, when the Cubs were tied for the National League lead on July 2, 1967, Randy had played in 74 straight games and caught both ends of all nine doubleheaders up to that point.21

On July 3, 1967, Randy’s two-run homer was part of a record-tying five round trippers by the Cubs and Atlanta Braves in the first inning. Billy Williams slugged a three-run homer and Ron Santo added a solo shot for the Cubs in the top half of the first; Felipe Alou and Rico Carty belted homers in the home half of the inning.22

As the first half of the ’67 season ended, sports writer Jerome Holtzman said Randy should get the club’s MVP honor. Holtzman cited the catcher’s .300-plus batting average and noted that Randy had caught every inning of 78 straight games.

“He is probably the finest defensive catcher in the league,” Holtzman wrote. “Moreover, he is now learning how to take charge of a game and is handling the Cub staff with the poise of an established veteran.”23

In 1968, Randy caught a major-league-record 160 games, which may help explain his unusually low .226 batting average that season.

Nevertheless, his manager said about Hundley, “His indispensable quality is fierce, aggressive leadership on the field. He advises, praises, scolds, and browbeats the pitchers and hollers at the infielders to keep them alert.”24

His best day at the plate in 1968 occurred during a July 28 doubleheader when he drove in three runs in the opener and doubled in the only run of Game Two of the Cubs’ sweep over the Dodgers–8-3 and 1-0–before 42,261 fans.

For Randy and other Cub mainstays such as Ernie Banks, Santo and Williams, the 1969 season was the highlight and lowlight of their time in Chicago. On August 14, the Cubs enjoyed a nine- game lead over the St. Louis Cardinals and a 10-game cushion over the New York Mets after being in first place for 155 straight days.

But the lead had shrunk to a half-game in early September when the Mets beat the Cubs twice in New York. Randy was in the middle of a game-deciding play in the 3-2 loss in the first game. With the Mets’ Tommie Agee on second base in the sixth inning, Wayne Garrett lined a single to Cubs’ right fielder Jim Hickman, whose throw to home appeared to beat Agee. But rookie umpire Dave Davidson called Agee safe for the third and deciding run. With that, Randy exploded and jumped into the air several times.

“I was there, and I know how hard I tagged Tommie Agee on the play,” Randy said years later. “The ball went from the pocket of my glove up into the webbing. I knew I couldn’t bump an umpire or I’d get suspended, so that’s why I tried to go straight up and down.”25

It only got worse for the Cubs when they lost twice to the Philadelphia Phillies, while the Mets rolled over the Montreal Expos four times, putting the upstart New Yorkers in first place for good.

Like most of the other Cub regulars, Randy’s performance at the plate declined greatly in September. On June 1, he was hitting .307 with eight homers, but he hit only .151 in the last month of the season.

Nevertheless, the ironman catcher was named to the National League All-Star team for the first time and led the league’s catchers in fewest errors and double plays turned by a catcher and tied for most games and assists. He also hit a grand slam and a double on May 28, 1969, in a 9-8 win over the Giants.

During 1966-69, Randy caught a remarkable 612 of his team’s 647 games. During his career, he caught both ends of a doubleheader 55 times.

As the 1970 season opened, Durocher announced Randy would be dropped to the eighth spot in the batting order after batting sixth much of the time. A chip fracture on his left thumb sustained in a spring training game against the Oakland A’s caused him to miss the first week of the season. It got worse for “The Rebel” when he tore the cartilage in his left knee during a collision with the Cardinals’ Carl Taylor at home plate on April 21. He missed 89 games in another disappointing season for Cub fans. However, the Cubs had a .612 winning percentage when Randy played.

Some believe Randy’s prolonged absence in 1970 may have cost the Cubs the National League East Division title. “He meant at least 10 games in the standings,” Durocher said in early September. “No one ran on him when he was catching, and he was a good hitter. They took away more than just a catcher. They took away my general out there.”26

Nevertheless, baseball scouts still rated Randy as the top defensive catcher in 1970, according to sportswriter Holtzman. He was followed by Bench, Jerry Grote of the Mets and Manny Sanguillen of the Pirates.27

The injury bugaboo struck again early in the 1971 season when he hurt his right knee during a rundown play in spring training against the California Angels. After missing the opener, he returned to action on May 12, only to reinjure the same knee three days later. He came back to pinch hit two weeks later wearing a special knee brace but collapsed after hitting a pop fly and was carried off the field on a stretcher. On June 3, he underwent surgery to fix a torn cruciate ligament and suffered an acute gall bladder attack. “We almost lost him,” one hospital spokesman said.28

Randy came back in 1972 to play in 114 games and catch rookie Burt Hooton’s no-hitter against the Phillies on April 16 and Milt Pappas’ no-hitter against the San Diego Padres on September 2. He was home recovering from a severed tendon in a toe when Ken Holtzman no-hit the Braves on August 19, 1969, before 37,514 fans at Wrigley Field. He also led the league’s catchers with a .995 fielding percentage and hit a grand slam off the Giants’ Don Carrithers on June 20.

Although Hundley played in 124 games and doubled his home run total the next season, his inability to throw out base runners was noticeable.

On December 6, 1973, Randy was traded to the Minnesota Twins for catcher George Mitterwald, reuniting him with his former battery mate Hands. “I found out about it through the papers and the radio,” Hundley said. “But aside from that, this has been a good organization to me. I wish the Cubs well.”29

Randy played in only 32 games for the Twins in 1974 as the result of damaging the cartilage in his right knee when he was pushed to the ground by Twins’ pitcher Ray Corbin during an argument at home plate on June 20.

Due to the nagging injury, he did not play from July 7 until he caught three innings of a game at Boston on August 18. After he consulted a Chicago doctor, he underwent surgery in September 1974 to repair the cartilage damage in his right knee. On October 25, 1974, he was taken off the Twins’40-man roster.

On April 3, 1975, the Padres signed Randy as a free agent after inviting him in February to spring training. He played in 74 games that season and was credited early in the campaign with the improvement in the Padres’ pitching staff.30 A year later, the Padres released the veteran catcher and offered him a job as a player-coach with Hawaii in the Pacific Coast League, but he declined.

However, on April 13, 1976, the Cubs signed Randy for his second stint with the franchise. Entering the lineup on the second day of the season, Randy started the winning rally with a double to right center off Mets’ reliever Bob Apodaca in the seventh inning of a 6-5 victory before 9,307 spectators. After reaching second, he looked down and prayed.

“I paused to give thanks to The Lord for letting me play baseball again,” said the former pre-game organizer of church services. “I was shook. What can I say? It was a very emotional moment.”31

But the injury bug struck Randy again when he sustained a cervical sprain and a stretched muscle in his left shoulder during an altercation between the Cubs and Giants in San Francisco on May 1 of that year. After being placed on the 15-day disabled list, he underwent surgery to remove a disc and fuse two connecting vertebrae in his neck on June 7, 1976, at Northwestern Memorial Hospital in Chicago. As a result, Randy played in only 13 games that season.

“I don’t know what my situation will be next year,” he said after the surgery. “If I don’t play, I’d sure be interested in coaching.”32

In December 1976, new Cubs’ manager Herman Franks named Randy as the club’s bullpen coach and emergency catcher. In two games that season, the Bruins’ former No. 1 catcher went hitless in four at-bats. He was released by the Cubs for the final time on October 12, 1977.

After a year as a major-league coach, Randy managed the Cubs’ rookie league team in Bradenton, Florida. In 1979, he was promoted to manager of the club’s Double A affiliate in Midland, Texas. During his two years in Midland, his team won one division title and almost won another.

“When I came home for my high school senior class’ tenth anniversary reunion (in 1970), I was playing in the major leagues,” he told the Martinsville Bulletin in December 1980. “I had hoped by the time I came back for my 20th reunion that I would be managing there. I’m not there yet, but I’m still working on it.”33

Randy was one step away from managing in the major leagues when he took over the Cubs’ Triple A affiliate in Des Moines, Iowa, in 1981. However, the Iowa Oaks got off to a 12-30 start and Randy was demoted by Director of Player Personnel C.V. Davis on June 1, 1981, which was Randy’s 39th birthday.

Instead of going back to Sarasota in the Florida State League, Randy returned home to Chicago to weigh his options. Ironically, Randy was replaced by former Toronto Blue Jays’ manager Roy Hartsfield, who had a 16-32 record at the time as skipper of Midland in the Texas League. Although the Oaks were 11 games out of first place when Randy was demoted, Hartsfield’s Midland team was in last place in the Texas League’s Western Division when the latter was promoted.

“We weren’t playing well here, but they aren’t playing well in Midland and they aren’t playing well in Chicago, either,” Randy told Des Moines Tribune columnist Marc Hansen after the surprising move.34

Expressing disappointment in the Oaks’ record, Randy said, “We’ve played poorly, there’s no question about that.”35 He added, “We were supposed to have a good club here, but no one considered what our competition would be. I can’t throw the ball for the pitchers. I can tell them what needs to be done, but I can’t execute for them.”36 As for going back to managing in the rookie league, he argued, “That’s absurd. Why should I have to go all the way back to the rookie league? I’ve given an awful lot of my life to the Cubs as a player and a manager, and now this. I’m just not going to the rookie league.”37

Fortunately for Randy, his connection to baseball didn’t end in 1981. A year later, he came up with the idea of operating baseball fantasy camps after talking to Chicago restaurant owner Rich Melman. Thirty-five years later, those camps in Mesa, Arizona, are still in business, much to the delight of diehard middle-aged and older Cub fans throughout the country.

“It never gets old putting on a uniform. I love doing the camps and I love what everybody else is getting out of it,” he said in 2010. “We were a family who enjoyed playing together, and to now let other people enjoy that with us has really been a fantastic experience all these years.”38

All campers receive a uniform with their favorite player’s number and hat, get tips from such Cub luminaries as Williams, Fergie Jenkins, Ryne Sandberg, Glenn Beckert, Don Kessinger, Bill Buckner, Jody Davis, Rick Reuschel, Lee Smith and Rick Sutcliffe, and participate in intrasquad games as well as one game against players from another major league team’s fantasy camp.

For Randy, the fantasy camps are all about reliving the emotions of a real major league camp.

“The wonderful thing about it is that everybody who goes has the same emotions that a big-league player has when they go to their first big-league spring training or get traded to another ballclub … All those emotions are the same and are the wonderful part about it.”39

Randy has received several other honors as a result of his Major League Baseball career. He was inducted on July 7, 1992, into the Martinsville-Henry County Professional Wall of Fame along with former Cub teammate J.C. Martin, Carl Hairston, Sonny Wade (football), and David Bailey (motorcross). He is in the Lou Boudreau Hall of Fame sponsored by the Pitch and Hit Club of Chicago, whose mission is “to be a preeminent baseball organization by recognizing and honoring the achievements of those in the baseball community.”40 On April 19, 2017, he and seven other former Cubs received World Series rings in conjunction with the Cubs’ first World Series title in 108 years in 2016.

Randy’s wife, Betty, passed away of breast cancer on September 4, 2000, at her home in Palatine, Illinois. She was 58 years old. In addition to Randy and her mother, Elva Foster of Bassett, Virginia, she was survived by her four children, a brother, a sister and eight grandchildren. A story eight days later in the Chicago Sun-Times said she “combined incisive baseball knowledge with a welcoming personality and a deep love of God.”41

Randy still attends the annual Cubs Convention in Chicago in January.

“The Cub fans don’t forget you and won’t let you forget them, either. I’m very proud to have been a Chicago Cub and played with that organization because I don’t know any other place where you could have a relationship like you do with the Cubs,” he commented.42

A main cog in the Cubs’ first division teams of the late 1960s and early ‘70s, Randy’s baseball career was curtailed by serious injuries that forced him to retire at age 35. Despite that, he is generally regarded as the second-best catcher in the team’s history behind only Hall of Famer Gabby Hartnett. And to this day, he is giving hundreds of middle-age adults and beyond a taste of what it’s like to attend a major league spring training camp.

Acknowledgments

The author is indebted to Director Pat Ross and the Bassett Historical Center in Bassett, Virginia, for providing several copies of newspaper articles about Randy and material from Bassett High School Yearbooks. This biography was reviewed by Joel Barnhart and fact-checked by Kevin Larkin.

Sources

Books

Chicago Cubs 1966 Official Press-TV-Radio Roster Book

Chicago Cubs 1967 Official Press-TV-Radio Roster Book

Chicago Cubs 1968 Official Press-TV-Radio Roster Book

Chicago Cubs 1969 Official Press-TV-Radio Roster Book

Chicago Cubs 1970 Official Press-TV-Radio Roster Book

Chicago Cubs 1971 Official Press-TV-Radio Roster Book

Chicago Cubs 1972 Official Press-TV-Radio Roster Book

Chicago Cubs 1973 Official Press-TV-Radio Roster Book

Chicago Cubs 2015 Media Guide

Internet

http://www.baseball-reference.com (http://www.baseball-reference.com)

http://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1964/BO9272CHN1964 (http://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1964/BO9272CHN1964

Archives

Baseball Hall of Fame Library, player file for Randy Hundley

Notes

1 “Cecil R. Hundley Sr.,” Martinsville Bulletin, February 3, 1987.

2 Bill Weekes, “Cecil Hundley’s Biggest Baseball Accomplishment Son’s Rise In Majors,” Martinsville Bulletin, June 29, 1969.

3 Bob Vorwald, What It Means To Be A Cub (Chicago: Triumph Books, 2010), 61.

4 Vorwald, What It Means To Be A Cub, 61.

5 Ibid.

6 Weekes, “Cecil Hundley’s Biggest Baseball Accomplishment Son’s Rise In Majors.”

7 Ibid.

8 John D. Bassett High School Yearbooks, 1959, 1960, from Bassett Historical Center.

9 John D. Bassett High School Yearbook, 1960.

10 Betty Onida Foster Hundley, https:findagrave.com/cgi-bin-/fg.cgi?page=gr&Grid=74678474 (https:findagrave.com/cgi-bin-/fg.cgi?page=gr&Grid=74678474).

11 Fred Mitchell, Cubs: Where Have You Gone? (New York: Sports Publishing, 2004), 114.

12 Cecil Randolph Hundley, Jr., Petitioner v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, Respondent. United States Tax Court. Filed June 19, 1967. http://leagle.com/decision/196738748aitc339_1353/Hundley%20v.%20Commi…

13 Hundley, Jr., Petitioner v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, Respondent. United States Tax Court.

14 Tom Mitchell, “Playing Days Remembered As Ex-Cub Toils As Manager,” Martinsville Bulletin, December 28, 1980.

15 Mitchell, “Playing Days Remembered As Ex-Cub Toils As Manager.”

16 Eddie Gold and Art Ahrens, The New Era Cubs 1941-1985 (Chicago: Bonus Books, 1985), 148.

17 “Native Bassett Big League Baseball Player Rests At Home in Collinsville For Winter,” Henry County Journal, February 8, 1968.

18 David Claerbaut, Durocher’s Cubs The Greatest Team That Didn’t Win (Dallas: Taylor Publishing Company, 2000), 34.

19 Carrie Muskat, Banks to Sandberg to Grace Five Decades of Love and Frustration with the Chicago Cubs (Chicago: Contemporary Books, 2001), 109.

20 Muskat, Banks to Sandberg to Grace Five Decades of Love and Frustration with the Chicago Cubs, 109.

21 Jerome Holtzman, “Hat’s Off!” The Sporting News, July 15, 1967.

22 “Cubs, Braves Tie Mark,” The Sporting News, July 15, 1967.

23 Jerome Holtzman, “Cubs Stagger at Halfway Point As Swatters Fall Into Swoon,” The Sporting News, July 22, 1967.

24 Gold and Ahrens, The New Era Cubs 1941-1985, 150.

25 Vorwald, What It Means To Be A Cub, 63.

26 “Hundley The Answer?” The Sporting News, September 4, 1971.

27 Jerome Holtzman, “An Ump Has Friends, After All,” The Sporting News, September 26, 1970.

28 Gold and Ahrens, The New Era Cubs 1941-1985, 150.

29 Richard Dozer, “Santo, After Long Count, Still in Cub Corner,” The Sporting News, December 22, 1973.

30 Phil Collier, “Padres Gloating: When Bell Rings, Siebert Is Ready,” The Sporting News, May 3, 1975.

31 Richard Dozer, “Old Idol Randy Brings Cub Fans to Life,” The Sporting News, May 1, 1976.

32 “Lost Year For Hundley,” The Sporting News, August 14, 1976.

33 Mitchell, “Playing Days Remembered As Ex-Cub Toils As Manager.”

34 Marc Hansen, “Should Cubs start from scratch?” Des Moines Tribune, June 2, 1981.

35 Gene Raffensperger, “Oaks’ Hundley out in Cubs’ shakeup,” Des Moines Tribune, June 1, 1981.

36 Raffensperger, “Oaks’ Hundley out in Cubs’ shakeup.”

37 Ibid.

38 Vorwald, What It Means To Be A Cub, 66.

39 Bob Vorwald, Cubs Forever Memories from the Men Who Lived Them (Chicago: Triumph Books, 2008), 25.

40 www.pitchandhitclub.org.

41 “Betty Hundley, 58, wife of former Cub,” Chicago Sun-Times, September 12, 2000.

42 Vorwald, What It Means To Be A Cub, 65.

Full Name

Cecil Randolph Hundley

Born

June 1, 1942 at Martinsville, VA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.