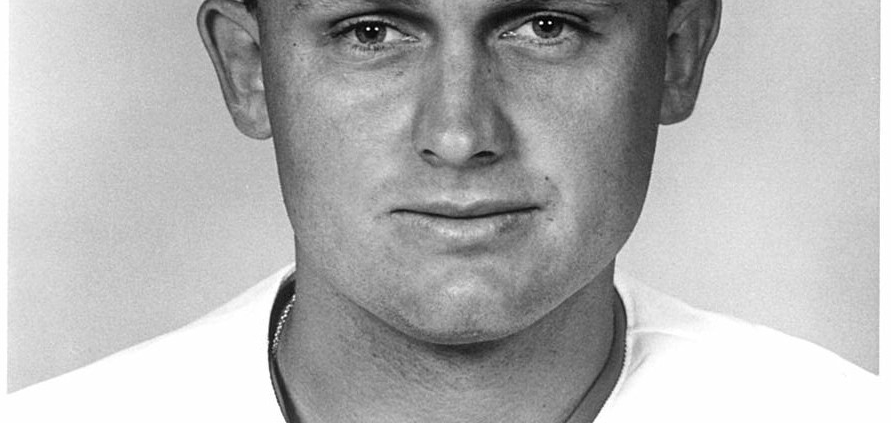

Randy Knorr

Randy Knorr spent 11 seasons as a catcher in the major leagues from 1991 to 2001, and 19 years overall in professional baseball, mostly as a backup catcher. Knorr appeared in 253 regular-season games at the major-league level and one postseason game. He played one inning of Game Five of the 1993 World Series. Knorr never batted but received two World Series rings with the 1992-93 champion Toronto Blue Jays. Knorr finished his career with Montreal in 2001 and remained with the organization in several capacities after it relocated to Washington, where he won another World Series ring in 2019 with the champion Nationals. No one can question Knorr’s persistence and determination: he appeared in 1,170 minor-league games.

Randy Knorr spent 11 seasons as a catcher in the major leagues from 1991 to 2001, and 19 years overall in professional baseball, mostly as a backup catcher. Knorr appeared in 253 regular-season games at the major-league level and one postseason game. He played one inning of Game Five of the 1993 World Series. Knorr never batted but received two World Series rings with the 1992-93 champion Toronto Blue Jays. Knorr finished his career with Montreal in 2001 and remained with the organization in several capacities after it relocated to Washington, where he won another World Series ring in 2019 with the champion Nationals. No one can question Knorr’s persistence and determination: he appeared in 1,170 minor-league games.

Randy Duane Knorr was born on November 12, 1968, in San Gabriel, California, to Carlos Ranson Knorr and Judith (Krumme) Knorr. After playing baseball for Baldwin Park High School, Randy was drafted by the Toronto Blue Jays in the 10th round of the June 1986 amateur draft. He attended his high-school graduation party at Disneyland and had no sleep by the time he stepped off the plane the next morning. He arrived at Medicine Hat, the Blue Jays’ Rookie Pioneer League affiliate in Alberta. “That was basically my first plane trip ever,” Knorr remembered. “They had to show me on a map where it was. I flew into Lethbridge and took a little prop into Medicine Hat, so I went from a nice comfortable ride to a knuckleball express.”1

He arrived bleary-eyed at 10 A.M. that first day. “They’re all waiting on me,” he remembered. “I walk in and they said, ‘Let’s go, we got to go out and hit.’ I said, ‘What?’ So, I go out and hit. They told me, ‘Go back to the hotel, get some sleep. You’re in the lineup tonight.” Sleep was not easy as the music blared at the Silver Buckle Hotel. The 17-year-old was hungry and went looking for a sandwich. He went into the lounge. “There’s this naked lady swinging down the pole. I go, ‘What a country.’ I just grabbed me a sandwich and sat right there in front. Watched her dance a little bit.”2 Knorr had two productive seasons at Medicine Hat, batting .277 with 14 home runs, but appeared in just 55 games his first season due to a dislocated shoulder.3

Perhaps the most important training Knorr received at Medicine Hat was his transition to catcher. Knorr spent his first season playing the familiar first base he had in high school. Blue Jays farm director Bobby Mattick had other ideas. During spring training in 1987, Knorr was asked to help warm up a pitcher. The next day, he found catcher’s equipment in his locker, thinking it was a mistake. He discovered it was not. Mattick soon had Knorr on his knees blocking pitches in the dirt. “He didn’t tell me how to do it,” Knorr said. “He just told me to get in front of the ball. The ball hit me in the ear and hit me in the chin. I took off all the equipment and threw it on the ground.”4

“I’m not doing this!” he yelled.

“Well, you can just go back home, then,” Mattick replied. By the time Knorr’s long career finished, he had played 1,201 games behind the plate, logging 1,698 innings at the major-league level. But it sure wasn’t easy in the beginning. “I was really horrible when I started,” he admitted. “No one wanted to throw to me. Balls were going back to the screen the whole time.” The toughest part, he said, was throwing to second base “because everything has to work so perfect.” But the mental focus required for the position was also demanding. “You have to be on your toes,” he said, “and it does wear and tear on you mentally after a while.”5

In 1988 Knorr was at Class-A Myrtle Beach, where he batted .234 with 9 home runs. He remained at the “A” level with Dunedin in 1989, batting .262 with six home runs. Knorr was on the Toronto 40-man roster in the spring of 1990, third on the depth chart for catchers behind Pat Borders and Greg Myers. But Knorr wasn’t called up that season because the Jays opted to give rookie Carlos Diaz a try. Knorr spent the entire year with Knoxville of the Double-A Southern League (.276, 13 home runs, 64 RBIs).6

Knorr spent three winters (1989-1991) playing for the Melbourne Monarchs and the Williamstown Wolves of the Australian Baseball League. “It was a great time,” he said. “I stayed at Black Rock Beach. I’m right on the ocean, and I walk across the street, and there’s a nude beach. Then, one year, we make the playoffs. It’s February 2, and I get a phone call at 2:00 a.m. – it’s Pat (Gillick, Toronto GM), and wants to know why I’m not in big-league camp. I was playing A ball, and they were inviting me to their camp.”7

Knorr began 1991 with Knoxville, then was promoted to Triple-A Syracuse, batting a combined .245 for the two teams. He was called up to Toronto near the end of the season and made his major-league debut on September 5 when he entered the game defensively in Cleveland in the bottom of the ninth with Toronto ahead, 13-1. His first at-bat was in the last game of the season, when he struck out against Allan Anderson. Knorr played three games for the AL Division champion Blue Jays, who lost to the Twins in the ALCS.

The 1992 season was a magical one for the Blue Jays and all of Canada as they won their first World Series title. Knorr spent most of the season at Syracuse but was recalled on July 31. At the trading deadline, the Jays sent Myers and reserve outfielder Rob Ducey to the Angels for reliever Mark Eichhorn. Knorr played eight games as Borders’ backup, starting five of them. Before he even unpacked his suitcase, Knorr was in the game on July 31, replacing Borders in a 13-2 rout over the Yankees. Knorr singled off Jerry Nielsen for his first major-league hit. On August 16 he smashed his first home run, off Cleveland’s Dave Otto. A few days later, Knorr tore ligaments in his thumb making a tag at the plate in Milwaukee, forcing him to miss all of September. He returned in time to be on the postseason roster but didn’t see any action in Toronto’s championship run.8

It was a different story in 1993, as Toronto sought back-to-back World Series titles. Knorr was with the Blue Jays all season, serving as Borders’ backup. He played in 39 games, starting 28 of them and batting .248. On July 19, the Jays were in a first-place tie with the Yankees, with the Orioles and Tigers each only a half-game back. Knorr batted .389 in 20 games (21-for-54) and had a .441 on-base percentage from that time on to the end of the season, helping the Jays win the AL East. On July 19 Knorr had a career-best three hits and three RBIs with a three-run home run in a 15-7 rout of Chicago. On September 1 he homered against Oakland in an 8-3 win that kept the Blue Jays 2½ games ahead of the Yankees. In the four final games of the regular season, September 28-October 1, Knorr was 7-for-14 and was just a home run away from the cycle on September 28. Toronto had all but wrapped up the division at that point. In nine starts since August 12, Knorr had 11 RBIs.

The Blue Jays defeated Chicago to return to the World Series against the Phillies. Knorr appeared in Game Five, his only postseason appearance, replacing Borders in a 2-0 loss. It was still memorable for Knorr. In the bottom of the eighth, his batterymate, Danny Cox, called time to chat with his catcher. “He tells me to settle down, look around where you are,” Knorr remembered. “You may never be here (World Series) again. That was an incredible moment for me, as I looked around at the crowd.”9 Joe Carter’s memorable walk-off home run in Game Six gave Toronto its second straight title.

Knorr revealed the managerial mindset he would use later in life by grilling pitcher Dave Stewart on what philosophy he used to get batters out. Or, just talking to anybody. “I talk to a lot of the guys as much as I can to be ready when I get to play,” Knorr said.10 “When I’m down there in the bullpen, I play games. I think of game situations, what to do with the hitters, trying to stay ready all the time.”11

Rookie Carlos Delgado made his major-league debut at the end of 1993 and many felt he was the heir-apparent to Borders as the Jays number-one catcher. Where would that leave Knorr? No one knew, but Knorr took advantage of his opportunities in 1994, batting .368 (.400 OBP) with four home runs in a 7-for-19 month of June. Knorr had a career-best day on July 23 against Texas. The Blue Jays pounded starter Hector Fajardo for six runs in the bottom of the first, including a two-run single by Knorr. He was just getting warmed up, homering off Fajardo in the fourth and reliever Rick Honeycutt in the eighth. Knorr finished 3-for-3 with 4 RBIs with three runs scored in addition to the two blasts. “I want them to think about me,” he said after the 9-1 victory. “I’ve been up for two years and I want them to say, ‘Hey, let’s give Randy a shot.’ I want (manager Cito) Gaston to come in in the morning and say, ‘I’m going to put Randy in there’ and not be worried about losing.”12 Knorr had seven home runs in 97 at-bats through July 23. There weren’t many opportunities left, however, as the players strike soon ended the season. Knorr batted .242 in 40 games that season.

Borders was a pending free agent after the 1994 season and Knorr made it known he felt he should be the starting catcher. “If they trade Pat and make Carlos (Delgado) No. 1,” Knorr said, “I want to go somewhere else.”13 The plan seemed to be a platoon situation with Knorr and Delgado. In hindsight, Delgado’s major-league debut in 1993 was the only game he would start behind the plate in the major leagues. He returned to the minors, learned to play first base, and his 336 home runs (of his 473 total in his 17-year career) rank first in Blue Jays history. Borders moved on, but Knorr was bumped from the top spot again. Just before Opening Day, the Blue Jays acquired 39-year-old veteran Lance Parrish from the Royals. Parrish was playing his 19th and final season.14 Much like his interactions with Stewart, Knorr welcomed Parrish’s insights on catching. “That man has played in the major leagues for 18 years. I’m going to milk him of everything he’s got if he’ll let me.”15

Knorr struggled defensively early in the season, allowing 22 stolen bases while throwing out only four runners through the end of May. The Royals alone had three players swipe two bases each in a game on May 23. Knorr quickly fell into Gaston’s doghouse, starting only seven games in June while Parrish started 16. Also in the mix was rookie Sandy Martinez, called up from Knoxville at the end of June. The problems continued for Knorr in June as he allowed 11 more stolen bases with just two caught stealing. “I’ve been struggling,” Knorr said in June,” but I’ve been around long enough that I know I can play. I just felt that rather than sitting around I’d like to be in there trying to get myself squared away.” He fractured a finger at the end of June and spent July rehabbing. It allowed him time to look at his mechanics on video. “It was a minor mechanical thing that caused a major problem,” Knorr realized. “I wasn’t keeping my shoulder square to the bag when I threw. I wasn’t using my legs, it was all arm and I just wasn’t getting any velocity.”16 Knorr returned in mid-August and showed improvement, allowing seven stolen bases while throwing out four in 16 games. He finished the season throwing out only 20 percent of basestealers (10/40), well below the league average of 31 percent. He batted just .212 with three home runs and the Blue Jays fell to fifth place (56-88). Martinez caught the bulk of Toronto’s games from that time on.

Knorr was sent back to Syracuse to begin the 1996 season, then was purchased by the Houston Astros for cash. His defense improved with his 37 Houston games: 12 stolen bases allowed and nine caught stealing (43 percent), but he batted a woeful .195. Houston assigned him to its Triple-A affiliate in New Orleans for the 1997 season. He returned to Houston for four games in September. Knorr was a free agent at the end of the season and signed a minor-league deal with the World Series champion Florida Marlins, who were quickly being dismantled. Knorr didn’t see much of Florida, anyway, since he was farmed out to Triple-A Charlotte. He finally returned to the Marlins for 15 games late in the season, batting .204.

Knorr returned to Houston for 1999 and was reassigned back to New Orleans, where he batted .352. He returned to Houston in early July and played in 13 games, batting .167. Knorr signed a minor-league contract with Pittsburgh in the offseason and played 13 games for its Triple-A affiliate in Nashville of the Pacific Coast League before being released. He signed with the Texas Rangers and was sent to Oklahoma, its Triple-A affiliate, where he spent most of the season. Knorr was granted free agency at the end of the season after appearing in 15 games with the Rangers, where he batted .294.

Knorr signed with the Montreal Expos for the 2001 season, and backed up 34 games for Michael Barrett. Manager Jeff Torborg, a backup catcher himself for 10 seasons, recognized where Knorr would one day be. “He hands me a lineup card, no names on it,” Knorr remembered of a day late in the season. “Then (Torborg) tells me to mark down what I should do with the names I’m filling in. Jeff didn’t second-guess me. I learned how to prepare a team, when to bunt, what to do in certain situations during a game.”17 Knorr played in his final major-league game on September 9, 2001.

From 2002 to 2004, Knorr finished his career with the Expos’ Triple-A affiliates, Ottawa and Edmonton. Eleven of his 19 professional seasons were with Canadian teams, starting with Medicine Hat (1986-1987), then Toronto (1991-1995), and the Montreal system (2001-2004). This did not go unnoticed by baseball fans in the Great White North. He was declared an honorary Canadian by fans of the Edmonton Trappers in his final season, 2004. “I’ve never had a bad experience in Canada,” he said, proudly. “I love it up here. It’s just been wonderful.”18 Knorr responded in gratitude by going 3-for-3 with a two-run homer in a Trappers win on the day he was honored.19

The Expos were considering assigning Knorr to be the hitting coach for their Vermont farm team but decided they needed his experience as catching depth in case of emergencies. “I really don’t know anything else,” he admitted. “I’m probably a lifer. I enjoy it. I like being out on the field.”20

Knorr began his coaching and executive career with the relocated Nationals’ franchise in 2005 and has remained through 2022. He managed Savannah of the Class-A South Atlantic League in 2005. From 2006 to 2008 he managed Potomac of the High Class-A Carolina League, and they won the league championship in 2008. In 2009 Knorr returned to the majors as bullpen coach for the Nationals. In 2010 he managed Harrisburg of the Double-A Eastern League. That year he also managed the Scottsdale Scorpions of the Arizona Fall League. In 2011 and 2018, Knorr managed Triple-A Syracuse and between those years served as Washington’s bench coach (2012-2015) and as a senior advisor for player development (2016-2017). In 2019 Knorr managed Fresno of the Triple-A Pacific Coast League. Through 2019, Knorr had managed 1,117 games in the minor leagues with a record of 546-571.

In 2020, when minor-league seasons were canceled because of the Covid pandemic, he ran the alternate site in Fredericksburg, Virginia. In 2021 Knorr was the Nationals’ first-base coach and in 2022 was named catching coordinator.

“I love being on the field, and developing players,” Knorr said in 2018. “What I look for in players, what I learned in the big leagues, how a player carries themselves away from the ballpark is equally important during evaluations.”21

Knorr was married to Kimberly (née Hartwell) for two decades. She was also from the Los Angeles area. They moved to Tampa, Florida, in the early 1990s. Kim studied journalism at Cal State Fullerton and taught Randy how to handle reporters. He was faithful to call her after each game and she could be a sounding board for him.

Tragedy struck on June 23, 2015, when Kimberly died suddenly at the age of 45. “Just when you think you’re getting over it, something comes up some days to make you think of her,” Knorr said in 2017. Kimberly battled rheumatoid arthritis. “Her liver gave out on her,” he said. “She had a lot of migraines because of the arthritis. Her body couldn’t take it anymore. I wasn’t prepared for it.”22 Kim founded the charity Wheelchairs4Kids, which provides equipment and organizes events for children with physical needs. The charity holds an annual golf tournament in her memory.23

The Nationals’ baseball community, Knorr said, is responsible for getting him through this devastating time. Fellow coaches and players rallied for him, even displaying a number-53 jersey in the dugout while Knorr was away. “There was no way I could’ve been alone,” Knorr said. “I couldn’t talk for three days or hold a conversation without breaking down. Not even on the phone. They did all that stuff for me. It’s so touching,” he said of all the support. “Being around them, I love these guys. It’s been great.”24

As of 2022, Knorr still awaited his ultimate dream of managing in the major leagues. It seems he could be a perfect fit for the right team, being a “genuinely positive and authentic guy,” wrote Anthony Oppermann of the Galveston County Daily News. “Knorr is an accessible man, the type of person who calls everyone by name, even the wait staff at restaurants. Even through the trials and tribulations of being in management and having to deal with difficult situations.”25

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted Ancestry.com, Baseball-reference.com, Familysearch.org, Myheritage.com, Retrosheet.org, Wheelchairs4kids.org, and the following:

Dougherty, Jesse. “Back in the Majors, Base Coach Randy Knorr Cares a Lot About the 90 Feet From First to Second,” Washington Post, June 29, 2021.

“Sam Narron, Randy Knorr, Bobby Henley Named Coordinators in Nationals’ Player Development Shakeup,” Washington Post, November 8, 2021.

“Knorr Named 11th Manager in Grizzlies History,” Hanford (California) Sentinel, January 9, 2019: D1.

Notes

1 Norm Cowley, “‘Wow! What a Country!’” Edmonton Journal, July 1, 2004: D1.

2 Adam Kilgore, “Bench Coach Randy Knorr Has Been with the Nationals Over the Long Haul,” Washington Post, March 30, 2012. Retrieved March 19, 2022, https://www.washingtonpost.com/sports/nationals/bench-coach-randy-knorr-has-been-with-the-nationals-over-the-long-haul/2012/03/30/gIQAvyvdlS_story.html. Robin Brownlee, “A Heroes Welcome,” Edmonton Journal, June 7, 1994: F2.

3 “Around the Minors,” The Sporting News, July 20, 1987: 42.

4 Norm Cowley, “Mattick Made Knorr a Catcher,” Edmonton Journal, May 31, 2003: C4.

5 Cowley, “Mattick Made Knorr a Catcher.”

6 “Notebook A.L. East,” The Sporting News, January 22, 1990: 42.

7 Don Laible, “Knorr Knows Value of Chiefs to Nats,” Utica (New York) Observer-Dispatch, April 20, 2018. Retrieved March 19, 2022. https://www.uticaod.com/story/news/columns/2018/04/21/knorr-knows-value-chiefs-to/12595833007/.

8 “Blue Jay Notes,” National Post (Toronto), October 1, 1992: 47.

9 Laible.

10 Associated Press, “Jays Get Straight A’s,” National Post, September 2, 1993: 38.

11 Tom Slater, “Given a Chance, Knorr Shows He Can Produce for Blue Jays,” Ottawa Citizen, September 7, 1993: E3.

12 “Jays Thriving With Knorr,” Victoria (British Columbia) Times Colonist, July 24, 1994: C2.

13 Steve Milton, “Knorr Makes Demand,” The Sporting News, March 21, 1994: 19.

14 Associated Press, “Parrish to Catch for Jays,” Hartford Courant, April 26, 1995: C4.

15 Mike Rutsey, “Knorr Eager for Increased Work,” National Post, April 25, 1995: 59.

16 Bill Lankhof, “Knorr Talks with Ash About Future with Team,” National Post, July 8, 1995: 74.

17 Laible.

18 Cowley, “‘Wow! What a Country!’”

19 “Trap Wrap,” Edmonton Journal, July 2, 2004: D5.

20 Cowley, “Knorr Shows Expos He Can Still Play the Game,” Edmonton Journal, April 30, 2004: D4.

21 Laible.

22 “From Heartbreak to Managerial Track for Former Montreal Expos, Toronto Blue Jays Catcher Randy Knorr,” National Post, March 30, 2017. Retrieved March 21, 2022. nationalpost.com/sports/baseball/mlb/from-heartbreak-to-managerial-track-for-former-montreal-expos-toronto-blue-jays-catcher-randy-knorr.

23 Jeff Rosenfield, “Celebs Tee It Up for Wheelchairs 4 Kids,” Suncoast News (Florida), February 9, 2021. Retrieved Mar 4, 2022.

24 James Wagner, “Nationals Organization Rallies Around Randy Knorr After His Wife’s Death,” Washington Post, September 25, 2015. Retrieved March 21, 2022. washingtonpost.com/sports/nationals/nationals-organization-rallies-around-randy-knorr-after-his-wifes-death/2015/09/25/cde0db1e-6150-11e5-b38e-06883aacba64_story.html.

25 Anthony Oppermann, “Thinking About You, Randy Knorr,” Galveston County (Texas) Daily News, July 6, 2015. Retrieved March 3, 2022. galvnews.com/sports/free/article_7f6bd0ca-2397-11e5-a142-7f8b760091e7.html.

Full Name

Randy Duane Knorr

Born

November 12, 1968 at San Gabriel, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.