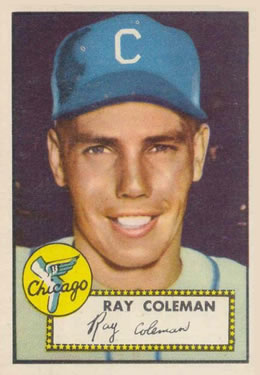

Ray Coleman

Throughout his career, Ray Cole man was beloved by nearly every manager, coach, and sportswriter for his ability to “put a lot of spirit into his game . . . [displaying] much of that ‘Gashouse Gang’ baseball.”1 After coming up as an outfielder with the St. Louis Browns in 1947, Coleman was traded to the Philadelphia Athletics the next season, only to be involved in a remarkable four additional transactions with the Browns over the course of his five-year major league career.

man was beloved by nearly every manager, coach, and sportswriter for his ability to “put a lot of spirit into his game . . . [displaying] much of that ‘Gashouse Gang’ baseball.”1 After coming up as an outfielder with the St. Louis Browns in 1947, Coleman was traded to the Philadelphia Athletics the next season, only to be involved in a remarkable four additional transactions with the Browns over the course of his five-year major league career.

Raymond Leroy Coleman was born on June 4, 1922, the eldest of two children of Orson Leroy and Ruby Leona (Gilmore) Coleman in Dunsmuir, California, a small city 200 miles north of Sacramento. During Ray’s childhood the family moved 45 miles north to Yreka, a former gold rush town that by the 1900s boasted a thriving timber industry. The son of a lumberjack, Ray “grew up riding pack trains into the mountains with grizzly old miners who carried saddlebags on their horses.”2 But the young Coleman had other accomplishments besides this. Ray attended Yreka Union High School where, under the tutelage of Yreka Miners athletic director Walter Foster, he excelled at several sports. He also served as the student council president during his senior year. Coleman also played American Legion baseball, and it was his baseball prowess that attracted the attention of Browns scout Kid Butler.

Originally slotted for the club’s Class-D Paragould Browns in the Northeast Arkansas League, in June 1940 Coleman instead made his professional debut with the Class-B Springfield, IL affiliate after the Indiana-Illinois-Iowa League entry was struck by a string of debilitating injuries. At 18, Coleman was the youngest non-pitcher in the circuit. Likely overawed by the competition, the left-handed hitter got just two hits in 22 at-bats before the return of the injured players permitted his assignment to Paragould. Playing with and against players of comparable age, Coleman rebounded with near team-leading marks in triples (9) and slugging percentage (.456) in 226 at-bats. He also gained recognition for his range in the outfield.

Coleman was reassigned to Class D again the next year—this time to the Mayfield (KY) Browns in the Kentucky-Illinois-Tennessee League. In July, he was selected as the starting centerfielder in the circuit’s All-Star Game while in route to a league-best 52 doubles and 122 RBIs. Coleman’s .346 average was second-best in the league. During the offseason, the Browns assigned him to the Class-AA Toledo Mud Hens—the club’s highest minor league affiliate—before a challenging 1942 spring training resulted in Coleman’s return to Class-B Springfield. After placing among the Three-I League leaders in doubles (25) and total bases (196), Coleman’s rise through the minors was abruptly halted during the offseason when he entered the US Navy.

In December 1942, the United States was entering its second year in the Second World War. “Seaman First Class Coleman was initially stationed at Treasure Island [in San Francisco Bay], California before embarking on overseas service that would take him from the Mediterranean to the Pacific.”3 Throughout the war Coleman served among an armed guard crew on maritime service ships that protected ammunition and supply transports. When the fighting ended he was mustered out of the service having participated in not a single baseball game during his three-year military tenure.

The rustiness of his long layoff did not initially affect Coleman when he returned to the Browns in 1946. Assigned to the Class-AA San Antonio Missions in the Texas League—Toledo had since been elevated to Triple-A status—Coleman’s .301 average midway through the season situated him among the circuit’s batting leaders. But he couldn’t maintain this pace, and got only 46 hits in his final 210 ABs to finish with a still respectable .287 average. But sorely missing in his stroke was any semblance of heft. Though far from a power hitter, in seasons past Coleman had exhibited a slugging percentage upwards of .420 with the occasional home run; in 1946 the percentage dropped to .364 with no homers.

The drop-off appeared to matter little to the Browns. The following spring Muddy Ruel, the club’s rookie manager, exclaimed that he saw “possibilities . . . in outfielder Coleman,” adding that the team had parted with veteran slugger Chet Laabs a week before the start of the 1947 season to clear roster room for the 25-year-old rookie.4 On April 22, Coleman made his major league debut at Cleveland Stadium pinch-hitting against Indians ace Bob Feller where he grounded into a force out at second base and was himself forced out at second on the next play. Coleman made his outfield debut four days later during a lopsided win over the Washington Senators. Inserted into the game in the seventh inning as a defensive replacement for right fielder Al Zarilla, Coleman came to bat in the bottom half of the frame and got his first major league hit—a two-run homer against righty Lou Knerr. A month later, on June 13, Coleman’s 10th inning triple proved to be the decisive blow in a 4-3 win against the New York Yankees.

But most of Coleman’s success came in a role as backup reserve, which didn’t change until June when Zarilla became immersed in a horrific batting slump that continued throughout the remainder of the season. Almost 75 percent of Coleman’s at-bats came in the second half. He finished with an average three points over the league’s .256, while almost leading the club with seven triples.

Just three years removed from the franchise’s first AL pennant, the Browns collapsed to a miserable worst-in-the-majors 95 losses in 1947, which prompted management to seek wholesale changes to the roster during the offseason. Some of the changes brought additional outfielders on board, so when spring camp opened, nine players were competing for three starting slots. Initially tabbed in February as one of the projected starters, Coleman was instead relegated to a reserve role during spring training, and he performed poorly. After almost six weeks into the regular season, Coleman had garnered just 29 at-bats in 17 games before being abruptly traded to the Athletics on June 5 for outfielder George Binks and $20,000. “[Coleman wi]ll help us,” pronounced A’s owner-manager Connie Mack. “He can run, and he knows how to get under a ball—and how to throw one.”5

Injuries to two of Mack’s starting outfielders had necessitated the trade, and Coleman worked out well. He helped spell the missing veterans by hitting .259 with five double, six triples and 20 RBIs in 189 at-bats until the injured players were able to return to the field. Used sparingly thereafter, Coleman got just two hits in 23 ABs (mostly as a pinch hitter) through the final two months of the season. The following spring the Athletics optioned him to Triple-A Buffalo (NY) Bisons in the International League. “[Coleman]’s only a step away from being a real good ball player,” Athletics farm director Art Ehlers explained. “But he needs regular play every day in order to develop.”6

Indeed, Coleman developed splendidly during his 1949 in Triple-A. Among the league’s leaders in nearly every offensive category, he became a favorite of Bisons manager Paul Richards for his ability to hit to all fields while rarely striking out. Indeed, Coleman helped lead the team to its first pennant in 13 years. Several major league clubs noted Coleman’s resurgence, among them, of course, his former employer in St. Louis. On December 13, the Browns sent third baseman Bob Dillinger and outfielder Paul Lehner to the Athletics for Coleman, infielders Billy DeMars, and Frankie Gustine, minor league prospect Rocco Ippolito and $100,000.

The youth movement begun by the Browns in 1947-48 was still in full ahead mode when Coleman reported to the club’s spring training in 1950. A young budding outfield composed of reigning AL Rookie of the Year Roy Sievers, rookie Ken Wood, and 22-year-old slugger Dick Kokos set Coleman a formidable challenge. But head-to-head competition for a starting spot became a moot endeavor, because Coleman contracted the flu in mid-March and was sidelined through a significant portion of camp. When the regular season began he was once again riding the bench.

The landscape changed rapidly two weeks into the season. On April 29 Colman replaced Sievers in centerfield, when the celebrated rookie of 1949 proved unable to maintain a batting average above his weight (185 pounds). Though he had his own struggles offensively—a .167 average in 54 ABs in May—Coleman was considered a much better fielder. Sievers reemergence in June coincided with Ken Wood’s two-month slump through July that afforded Coleman continued play. As Art Ehlers had predicted, he thrived with regular play: Coleman was one of the Browns hottest bats from the end of May to early September, hitting .318 in 233 ABs. He finished the season tied for the club lead in triples (6), was runner-up in stolen bases with seven, and among the team leaders in nearly every other offensive category.

Coleman’s offensive surge continued into the 1951 season, his sole career year in his short major league career. One of the few fan favorites on a team headed for its second 100-loss season in three years, Coleman’s 11-game hitting streak in June enabled him to maintain a perch among the league leaders in hitting since the start of the season. Coleman also drew lavish praise from Browns management for the mentoring of his younger teammates. “That boy has come a long way in the past couple of years,” Browns manager Zack Taylor exclaimed. “He spends hours on the ball field, practicing his hitting, his fielding and his throwing. . . . He has become a thorough student of the game and I now advise youngsters on my club to watch Ray. . . . He’s a wonderful help to those kids; always glad to show them what he knows about hitting.”7 It therefore came as a surprise to many observers when Coleman was selected off waivers by the Chicago White Sox.

Though the move was one of many that came in the wake of Bill Veeck’s July purchase of the club, observers were stunned that the Browns had received nothing in return for one of its few productive players. (Some sportswriters would later point to the Coleman move as the predecessor to a November 27 eight-player trade between the Browns and White Sox, a claim the latter club vehemently denied.) But from Coleman’s perspective he was delighted: the move not only placed him on a contending team but reunited him with his former Buffalo Bisons manager Paul Richards. Though Coleman’s hopes of postseason play were not realized, he remained a fixture in the White Sox outfield throughout the remainder of the season. He finished with career-high marks in almost every offensive category, including another near-miss major-league best of 12 triples.

At least twice during the offseason the White Sox offered Coleman to the Detroit Tigers in varied packages in an unsuccessful bid to acquire outfielders Johnny Groth and Pat Mullin. After these attempts failed, Coleman reported to the White Sox 1952 spring training. A slow starter throughout his career (1951 being the exception) Coleman struggled throughout exhibition play with a .135 average, an anemic performance that carried deep into the regular season. Plus on July 14 he suffered the indignity of being picked off first base by Athletics first baseman Ferris Fain’s excellently executed hidden ball trick. Exactly two weeks later Coleman was traded back to the Browns alongside catcher Jay Porter for catcher Darrell Johnson and outfielder Jim Rivera. On September 26, after paltry playing time, Coleman entered the fourth inning of a game against the White Sox as a defensive replacement in what proved to be his last appearance in the major leagues. Two weeks after the season ended Coleman was traded to the Brooklyn Dodgers with pitcher Bob Mahoney, shortstop Stan Rojek and $95,000 for infielder Billy Hunter.

In an attempt to resurrect his career, Coleman, for what is believed to be the only time in his career, traveled to Cuba to play winter ball during the offseason. Among the league leaders with a .403 average through December, Coleman reported to the Dodgers 1953 spring training with renewed confidence. Unfortunately, the reigning NL champion Dodgers, who were also pennant-bound in 1953 and sported a superb outfield comprised of future Hall of Famers Jackie Robinson and Duke Snider, plus Carl Furillo, did not have spare roster space for an extra outfielder. So Coleman was sent to the Triple-A St. Paul (MN) Saints in the American Association. He remained in the Dodgers organization into the 1954 season before being released.

In 1955, having seemingly hit rock-bottom, Coleman signed with the Class-D Mayfield Clothiers (the small Kentucky city had become his adopted hometown after having played there in 1941). A 22-game hitting streak at the end of the season renewed Coleman’s confidence enough for him to tryout with the Class-AA Birmingham (AL) Barons the following spring. He made the team in April only to be released a month later. After a brief stint with the Mobile (AL) Bears, Coleman signed with the Triple-A Omaha (NE) Cardinals where he served as a player-coach. Released by the Cardinals in October, the 34-year-old outfielder retired with a batting line of .258/.318/.374 in 1,729 major league at-bats.

Coleman had adopted Mayfield because he married a girl from there, Sara Jane Hackney, in September 1941. The union produced two daughters before ending in divorce in 1981. During his 40-year post-playing career Coleman was employed with the American Snuff Company, served as a construction foreman, and farmed tobacco and soybeans. In the 1980s he returned to Northern California where he worked as a medic.8

During his playing career Coleman spent several off-seasons hunting with such St. Louis Cardinal notables as Stan Musial, Red Schoendienst and Marty Marion; his passion for the outdoors did not end with his career. Moreover, Coleman was a renowned storyteller and became a great source for the official newsletter of the St. Louis Browns Historical Society.9

In the late 2000s Coleman moved to Oklahoma. On September 18, 2010, three months after his 88th birthday, he died in Norman, Oklahoma.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the notes, I also consulted Ancestry.com and Baseball-Reference.com. Thanks also to Yreka Union High School administrative assistant Kristen Brown and SABR members Bill Mortell for research assistance, and Tom Schott for review and edit. This biography was fact-checked by Stephen Glotfelty.

Notes

1 Dent McSkimming, “Hats Off: Ray Coleman,” The Sporting News, July 9, 1947: 19.

2 Rich Marazzi and Len Fiorito, Baseball Players of the 1950s: A Biographical Dictionary of All 1,560 Major Leaguers (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 2009), 73.

3 Gary Bedingfield, “Ray Coleman,” Baseball in Wartime, December 24, 2007. http://bit.ly/2BkgYAJ. Accessed January 9, 2018.

4 J.G. Taylor Spinks, “Muddy Moves into the Middle—and Likes It,” The Sporting News, May 7, 1947: 4.

5 Art Morrow, “Mack Shifts—Opens Wallet,” The Sporting News, June 16, 1948: 13.

6 The Sporting News, “Two Players Among Souvenirs Collected by Athletics in Cuba,” April 6, 1949: 10.

7 Ray Gillespie, “Hats Off: Ray Coleman,” The Sporting News, June 20, 1951: 19.

8 “Ray Coleman: Biographical Information,” Baseball_Reference.com. http://bit.ly/2D4GUUU. Accessed January 11, 2018.

9 Ray Gillespie, “Coleman Joins Return Parade of Old Brownies,” The Sporting News, August 4, 1952: 7; Gary Bedingfield, “Ray Coleman,” Baseball in Wartime. http://bit.ly/2BkgYAJ. Accessed January 9, 2018.

Full Name

Raymond Leroy Coleman

Born

June 4, 1922 at Dunsmuir, CA (USA)

Died

September 18, 2010 at Norman, OK (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.