Ray Herbert

Ray Herbert entered professional baseball at the age of 19 with the sinking fastball that major-league franchises dream of, but lacked the knowledge and skill to convert his great “stuff” into immediate success. For 11 years he toiled with mostly second-division teams, both in the majors and minors, rarely winning more than he lost, surrounded by ineptness. Then, in 1961, he became a member of the Chicago White Sox, where, over a three-year period, he won 42 games.

Ray Herbert entered professional baseball at the age of 19 with the sinking fastball that major-league franchises dream of, but lacked the knowledge and skill to convert his great “stuff” into immediate success. For 11 years he toiled with mostly second-division teams, both in the majors and minors, rarely winning more than he lost, surrounded by ineptness. Then, in 1961, he became a member of the Chicago White Sox, where, over a three-year period, he won 42 games.

Raymond Ernest Herbert was born in Detroit, Michigan on December 15, 1929, to Oliver and Iola (Fredette) Herbert. Oliver, a deliveryman for Silvercup Bakery, played hardball for semipro teams in the Detroit area, and raised his daughter, Patricia, and three sons, Ray, Don, and Dick, to be active in sports and to cheer for the Detroit Tigers. Ray achieved great success as a pitcher at Detroit Catholic Central High School, leading his team to the Catholic First Division Championship in both 1947 and 1948, including an 11-0 won-lost record and two no-hitters; brother Don was his batterymate during his junior year. After his senior season in 1948 he signed with the hometown Detroit Tigers for $4,000 under the guidance of local Tigers scouting legend “Wish” Egan.1

Herbert began his professional career with the Toledo Mud Hens, Detroit’s AAA club in the American Association. This was, perhaps, a very high level for a young man to start his career, but the Tigers had done it before — and with success. Other Detroit teenagers — Hal Newhouser and Art Houtteman — had succeeded at the major-league level with the Tigers, so why not Herbert? Pitching against the Kansas City Blues on April 25, 1949, Herbert twirled a complete game (seven innings), two-hit shut-out, winning the second game of the doubleheader, 3-0. The success did not last, however, as Herbert finished the year with a 6-17 record and a 5.81 ERA. His efforts were not helped much by his teammates; Toledo had a 64-90 record, the worst in the league, precipitated by the worst fielding. Toledo wasn’t much better the following year, but Herbert made strides; his record improved to 11-12, and his ERA dropped by more than two runs-per-game (3.69). Herbert did get a brief reprieve from Toledo’s travails late in 1949 when he was called up by the Tigers; the club was, at the time, fighting for the American League pennant.

Herbert made his major-league debut at Philadelphia on August 27, 1950, as the Tigers starting pitcher, losing a complete-game effort 4-3 on a late homer by Sam Chapman. The 5-foot-11, 180-pound righty was able to even his record three days later in relief against the Washington Senators. Entering the game down by a run, he held the Senators scoreless for 2⅔ innings, while his teammates exploded for three runs in the ninth. By season’s end, the Tigers had faded to finish second, three games behind. Herbert had started two more games in the thick of the pennant race, but had been given an early fifth-inning hook in both. His last four appearances were in relief, an indication of his future role on the Detroit staff.

But the Tigers’ plans for Herbert in the 1951 season had a big caveat — Herbert’s military requirement. The team knew they would lose him early in the season, and perhaps that sealed his fate to duty in the bullpen. Herbert appeared in five early-season games, all in relief. While his effectiveness was not dominant — 17 baserunners in 12⅔ innings — the results were spectacular, four winning decisions in five appearances. Twice, the young pitcher gave up a go-ahead run but was bailed out by a winning Tigers rally. Herbert’s wildness had to be disconcerting to Tigers management — but 4-and-0 was 4-and-0.

Herbert joined the Army in May, and was stationed at Fort Custer, Michigan, for the next two years, serving as corporal with the military police and pitching dominantly for his service team. In June of 1952, while in the service, he married Merrilyn Nickols, a hospital employee from Battle Creek. The Herberts’ first child, daughter Roxan Marie, was born the following February.

In 1953, Herbert, anxious to resume his career, had saved up furlough time to attend spring training, and arrived in time to pitch in three early-season games. But he did not resume his career full time until May 18; by then, the Tigers were already mired in the cellar, with a 9-22 record, 11 games out. Herbert returned to the Tigers’ staff for the 1953 season, but not to a settled role, unless “mop-up” is a role. He appeared in 43 games, three of them starts, with a 5.24 ERA. Wildness continued to plague him, specifically with breaking pitches, and his fast ball, though very good, was not enough to succeed by itself. But over the last two months of the season, Herbert was given the ball late in games where the Tigers were ahead, an uncommon occurrence, and he managed to do well.2 The Tigers again, if only briefly, had hope for his future.

Ray Herbert was given the start for the second game of the Tigers’ 1954 season, on April 14, facing the weak Baltimore Orioles in Detroit; the outing was far from successful. Herbert allowed five of the eight batters in the first inning to reach base; three of them scored. When the first two batters reached in the second, Herbert was removed. The Tigers lost 3-2, the first loss in a long, unhappy season. Herbert was relegated to the bullpen, then given a chance to redeem himself with a start on May 29 at Cleveland; he lasted 1⅓ innings, the loser in a 12-0 Indians’ romp. The Tigers finished the season 68-86, fifth in the American League. Herbert was 3-6 with a 5.87 ERA, bad enough; even worse was his 1.945 WHIP. No pitcher could succeed while allowing two men on base per inning.

The Sporting News had Herbert tabbed as the top man in the 1955 Tigers’ bullpen,3 but it didn’t pan out. On May 11, Herbert’s contract was sold to the Kansas City Athletics for an estimated $20,000.4 The deal was not a surprise. The Tigers, 15-11, in third place, had not found one instance where Ray Herbert’s pitching skills might be of use. The Detroit Free Press stated that “he’s been in manager Bucky Harris’ ‘dog house’ all spring.”5 In Kansas City, Herbert “particularly pleased” to be an Athletic, told reporter Ernest Mehl “What I want is work. All I did in Detroit was pitch batting practice and that’s not enough.”6 The Herberts, now parents to a second daughter, Melanie7, purchased a mobile home as their residence, and headed west.

Ray Herbert and his family were going to a very different atmosphere in Kansas City. The Tigers and their fans were spoiled by the success of the 1940s, also goaded by comparisons to the championship teams of the local football Lions (with Bobby Layne), and the hockey Red Wings (with Gordie Howe). But the Athletics’ fans had a brand new (albeit historically unsuccessful) franchise, with no other local pro teams to compete with.

In a “wives interview” with the Kansas City Times,8 Merrliyn Herbert expressed her satisfaction: “I am glad Ray is with the Athletics now. Mr. [Lou] Boudreau is a wonderful manager. He gives his pitchers a chance to build self-confidence by not pulling them out of a game as soon as they seem to falter.”9

Herbert’s first season in Kansas City was much like 1954 in Detroit: A 1-8 record, a few starts, mostly mop-up relief stints; his walk rate and WHIP became marginally better, but nowhere near acceptable. At age 25, he had become a major-league journeyman. Rather than let him waste away, the Athletics sent him back to the minors for seasoning and education; this time he accepted the demotion.10

Herbert spent two entire seasons in the International League (AAA), with the Columbus Jets in 1956, and the Buffalo Bisons in 1957. In Buffalo, he was re-acquainted with the experience of winning as the Bisons went 86-66, missing the league championship by half a game, then going deep into the Junior World Series before losing to Denver in the finals. Herbert’s 13-8 record was accompanied by much better control and a manageable WHIP; although teammate Walt Craddock had a more impressive 18-10 record, Herbert had become manager Phil Cavarretta’s most reliable pitcher as the season wore on. The Athletics now saw him as a viable asset, and a candidate for the Athletics’ staff.

Ray Herbert came back to the Athletics to stay at the start of the 1958 season, competing for starts with Ned Garver, Ralph Terry, and Jack Urban. He compiled an 8-8 record for an Athletics team which was a pleasant surprise with a 73-81 record; optimism abounded. Kansas City pitching coach Johnny Sain, a teammate of Herbert’s with the Tigers who described Ray’s progress “He has perfected a good curve to team with his fastball, and is developing a better change of pace.”11 Sain later remarked, referring to Herbert, that “it is not unusual for the length of time it takes for a young pitcher to find himself.”12

The Athletics regressed to a 66-88 record in 1959, 63-91 in 1960. But Herbert, along with Bud Daley, became the stalwarts of the pitching staff, combining for 57-55 record while the team was 129-179 during the two-year period. Athletics owner Arnold Johnson had died, and general manager Parke Carroll along with personnel manager George Selkirk were pulling straws to find an effective manager: Harry Craft (1958-1959), then Bob Elliott (1960), then Joe Gordon (at the start of 1961) had each tried. Both the 1959 and 1960 seasons might have been much better for Herbert had his team and health been more stable. “I would have won 15-18 games in 1959 if not for the cold in my back. I couldn’t follow through well.”13 In 1960, after a tremendous spring (only 9 hits in 18 shutout innings) and winning his first two starts, Herbert continued to have good stuff, but went through a frustrating 1-10 losing stretch before finishing 14-15. His 3.28 ERA was much better than the league average, 3.87; his wildness from the early years had disappeared. The woeful Athletics, despite the steady performances by Herbert and Daley, had given up 141 more runs than they had scored (615-756).

And then the whole franchise was turned on its head. On December 20, 1960 Charles O. Finley bought controlling interest in the Athletics for $2 million; on January 3, 1961, Finley hired Frank “Trader” Lane as general manager and executive vice-president. The new leadership would insure that no Kansas City player was immune to being traded. Upon arriving in Kansas City, Lane pointed out the many flaws in the Athletics’ personnel; he did, however, point out that both Herbert and Daley were “outstanding pitchers.”14 Herbert believed Lane’s estimation, and refused to sign his contract; Lane’s admiration became a bit dissipated. “I have been attacked before, but never so inexpertly,” Frantic Frank remarked.15 And Herbert’s “inexpert response” to his new general manager? “Lane told me I could do one of three things with the contract: sign it, hang it on the wall, or tear it up. So I tore it into little pieces and sent it back to him.”16

Herbert eventually signed a contract, and was named the A’s starter for the opener in Boston on April 11. Herbert and the A’s won the game, although he exited the game after six innings with a slight groin pull. He continued to make his starts, but was ineffective. After a loss in New York to the Yankees, he had a 3-6 record with a 5.38 ERA. He had been pummeled for nine hits by the Bombers, including long home runs by Mickey Mantle and Roger Maris. The next day he was part of an eight-player trade with the White Sox: Herbert joined Don Larsen, Andy Carey, and Al Pilarcik in going to Chicago, while the Athletics received Bob Shaw, Gerry Staley, Wes Covington, and Stan Johnson. Larson, Carey, Shaw, Staley, and Covington all had World Series credentials — they were on baseball’s list of household names — but all appeared to be receding from their days of glory.

Herbert seemed to have no luck — he was again going to a losing team. The Sox had been American League champions only two years before, but now they were struggling, in ninth place with a 19-32 record; they even trailed Herbert’s former team, the A’s, by 4½ games. But the move seemed to rejuvenate Ray. In his first appearance with the White Sox on June 14, he pitched a complete-game, three-hit victory over the Angels, winning 4-1. And the success continued to the end of the season: Herbert was 9-6 with the Sox, finishing with a 12-12 record after the mediocre start in Kansas City; the ugly ERA with the Athletics had receded to a somewhat more palatable 4.55. The White Sox had rebounded, going 67-44 after the June trade to finish with an 86-76 record, in fourth place.

Upon arriving in Chicago, Herbert had come under the tutelage of pitching coach Ray Berres –who had been watching the righty for a long time — and had plenty to say. “You get too many pitches inside to right-handed hitters. The ball you want to get away from right-handers, you’re bouncing into the dirt.” Berres described Herbert’s wind up as bringing his head forward during the wind up “like you’re ready to have your picture taken — the ‘Spaulding Guide look.’ And when you do that, the body sneaks forward, and you throw inside.”17

The effects of Berres’ instruction were gradual. Through mid-June, 1962, Herbert had made twelve starts, with a 4-4 record and mediocre 5.04 ERA. But on June 20, Ray pitched a one-run, complete-game win against the Minnesota Twins; Berres’ ideas had caught up with Herbert’s mechanics. Over his last 22 starts, Herbert compiled a 16-5 record, giving him a 20-win season with 12 complete games. His improved showing was enough to get him a roster spot for the second All-Star Game.18 Herbert pitched the middle three innings for the American League team, getting the win.19

Ray Herbert was never called upon to pinch-hit in his 14-year major-league career, but he could handle the stick, compiling a .192 average with seven homers and 21 doubles. Toward the end of his productive 1962 season, he had what might be called his “Babe Ruth moment”: He called his own home run. In a 9-3 laugher in Boston, Herbert came to the plate in the ninth inning, facing 27-year old rookie Hal Kolstad. While Kolstad warmed up, Herbert chatted with on-deck hitter Jim Landis: “This kid is going to think “this is just a pitcher” and throw me a fast ball — and I’m going to hit it out of the park.” Herbert did just that. When he got back to the dugout, all his teammates – instigated by Landis – turned their backs in mock disgust.20

Herbert was named to start the 1963 season opener at Detroit. The Sox won 7-5, but Ray was knocked about, giving up four runs on eight hits in 1⅓ innings. He came back to pitch a shutout against the A’s on April 18, and the outing set the stage for Herbert’s 1963 theme — the shut out. After a bad outing at Boston, a 9-5 loss, Herbert turned invincible. On May 1 – against the Orioles – Ray pitched a four-hit shutout. He then pitched shutouts against the Senators, Yankees, and Tigers in succession; on May 14, his record stood at 5-1 with a 1.81 ERA.

Seeking his fifth straight shutout, Herbert faced the Orioles in Baltimore on May 19, the second game of a doubleheader. Ray got through the first two innings unscathed, but Oriole catcher John Orsino ripped the second pitch of the third inning, sending the ball into the first row of the left field stands.21 The Sox argued fan interference to no avail. Orsino touched up Herbert for a second homer in the fifth, but the Sox went on to win the game, 4-3. The win, though, went to reliever Jim Brosnan, who had replaced Herbert in the bottom of the ninth, and gave up the tying run before Chicago rallied.

Herbert struggled to win throughout the rest of 1963, finishing at 13-10. His 3.24 ERA22 was better than average for the league (3.63), but pedestrian for the Sox (2.97), led by Gary Peters and Juan Pizarro. The White Sox won 94 games and finished second, 10½ games behind the powerful championYankees. Herbert led the league with seven shutouts, but age was creeping up on him.

The White Sox rotation for 1964 — Peters, Pizarro, Joe Horlen, and John Buzhardt – would again easily surpass all other American League pitching staffs, and none of the four were over the age of 27. Ray Herbert, now age 34, was sliding down the Sox depth chart. He began to experience arm trouble. Herbert complained of elbow tenderness on May 24, and again on June 5, both times from swinging a bat while batting during a game. The June incident ended with a diagnosis of a torn flexor muscle, and a trip to the 30-day disabled list.

When Herbert returned in July, the dominant pitcher of the previous spring was hard to find. His vulnerability was shown when Mickey Mantle stepped to the plate on August 12, and hit one of the longest home runs in baseball history, clearing the 461-foot mark on the center-field wall of Yankee Stadium by 15 rows.23 Herbert finished the year with a 6-7 record and 111 2/3 innings pitched, approximately half the number he had delivered each of the previous four years.

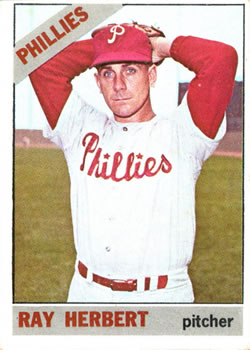

Ray Herbert’s tenure with the White Sox ended on December 1, when the Sox traded him and outfielder Jeoff Long to the Philadelphia Phillies for Danny Cater and Lee Elia. The Phillies had barely missed the 1964 National League pennant, due primarily on a need to work their two best pitchers — Jim Bunning and Chris Short — to a frazzle. Herbert’s excellence was not that far in the past, and Phillies manager Gene Mauch could envision him as much needed asset. Cater, an outfielder, had had an impressive 1964 rookie season at the plate before breaking an arm — and the Sox were always looking for more hitting.

Herbert made 19 starts for the Phillies in 1965, then tailed off to a mere 50 innings pitched in 1966. The Phillies released him and his playing career came to an end at the age of 36. He had recorded a 7-13 record in his two years in Philadelphia, bringing his lifetime major-league record to 104-107 with a 4.01 ERA.

After retiring from the Phillies, Herbert and his family continued to live in the Detroit area. Herbert had been employed by Montgomery Ward as a sporting goods department manager during the offseason, and now this became his full-time occupation. Herbert continued to be involved with baseball, working as batting practice pitcher for the Tigers from 1967 to 1992 when the team was at home. He was also president of the Detroit Tigers Alumni Association. The Tigers appreciated Herbert enough to include him with their traveling group for playoff games, and for the World Series in 1968 and 1984.

In retirement, in 2018, Ray Herbert lived in Stanwood, Michigan with his wife, Patricia. Herbert died after a long battle with Alzheimer’s Disease on December 20, 2022.

Last revised: June 30, 2023 (zp)

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Bill Nowlin and fact-checked by Kevin Larkin.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also used the Baseball-Reference.com and Retrosheet.org websites for player, team, box score, and season pages, pitching and batting game logs, and other material pertinent to this biography.

Notes

1 Lyall Smith, “Army Taps Herbert to Sap Tiger Mound Strength,” Detroit Free Press, May 11, 1951: 26. The Phillies offered $18,000, but Herbert turned it down to avoid the bonus rule stipulation of having to immediately start his career with the parent team; Don Herbert also signed with the Tigers as a catcher, playing one season of Class-D ball. Egan had also signed Detroit Central Catholic star Art Houtteman a few years before. The boys’ fathers were sandlot competitors. Art Houtteman won 15 games for the Tigers in 1948 at the age of 22; perhaps this unfairly set up expectations for Herbert in his years with the Tigers.

2 If the concept of relief pitching “saves” was becoming an important element in baseball, the 1953 Detroit Tigers hadn’t gotten the message. Herbert had earned six saves, by current computations; these were the most “saves” for a Tigers team since 1948 when Art Houtteman earned 10; Detroit’s reaction was to stop using Houtteman at the end of games for the remainder of his Tigers career.

3 Watson Spoelstra, “Kuenn Impressed by Tigers’ Showing — Not His Own,” The Sporting News, April 6, 1955: 6.

4 “Newhouser Given Outright Release,”Detroit Free Press, May 12, 1955: 29.

5 Harris’ demeanor probably turned sour when Herbert refused to accept a demotion to Buffalo (AAA).

6 Ernest Mehl, “New Players Happy to Join A’s,” Kansas City Times, May 13, 1955:31

7 Herbert and his wife would also have two sons: Raymond Mark and Mathew.

8 “Wives of the A’s,” Kansas City Times, July 12, 1955: 8.

9 Herbert had been given five starts in the month of June. He had a 1-4 record, but pitched two complete games and went deep into the other three.

10 See notes 4 and 5 regarding Herbert’s different reaction in Detroit in 1955.

11 Ernest Mehl, “Cerv Swings Pen for $32,500,” The Sporting News, March 11, 1959: 24.

12 Ernest Mehl, “A’s Pitchers Fail to Keep Step with Craft’s Clouters,” The Sporting News, May 20, 1959:14. Sain probably was reflecting on his own history. His career had been interrupted by three years in the service, and he was not able to prove himself in the majors until the age of 28.

13 Ernest Mehl, “A’s Jell after Skidding Start,” The Sporting News, May 4, 1960: 27.

14 The Sporting News, January 11, 1961: 4.

15 Ernest Mehl, “Finley Woos Players, Fans to Give A’s ‘Happy Family’ Air,” The Sporting News, March 1, 1961: 23.

16 Bob Vanderberg, Frantic Frankie Lane (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland and Company, Inc., 2013), 114.

17 Bob Vanderberg, SOX From Lane and Fain to Zisk and Fisk (Chicago: Chicago Review Press, 1984), 115.

18 Herbert was named as a replacement for pitcher Ken McBride of the California Angels who had developed pleurisy in his back.

19 The game was played July 30 at Wrigley Field in Chicago, won by the American League, 9-4. Herbert gave three singles over three scoreless innings.

20 Flyingsock.com. April 3, 2007 interview conducted by Mark Liptak.

21 In the 38 shutout innings, Herbert had given up 16 hits and three walks, a WHIP of 0.50.

22 Herbert expressed frustration with the computation of ERA in a Chicago Tribune article written by Richard Dozer on May 12, 1963. Herbert listed seven situations where he believed earned runs were the fault of lapses by the fielders rather than the pitching — and should be charged as such.

23 Even in the earlier struggles of his career, Herbert had not been especially susceptible to the gopher ball. He had led the American League in avoiding home runs in 1962 — one homer every 18 innings– and was in the league’s top 10 two other years.

Full Name

Raymond Ernest Herbert

Born

December 15, 1929 at Detroit, MI (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.