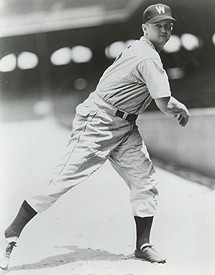

Roger Wolff

The 1945 Washington Senators1 intrigued war-weary baseball fans with an improbable pennant run. The team’s success stemmed largely from a unique pitching staff, dominated by four knuckleballers. The top performer was Roger Wolff, a journeyman right-hander who led the team with a career-high 20 wins.

The 1945 Washington Senators1 intrigued war-weary baseball fans with an improbable pennant run. The team’s success stemmed largely from a unique pitching staff, dominated by four knuckleballers. The top performer was Roger Wolff, a journeyman right-hander who led the team with a career-high 20 wins.

The second of ten children born to Leo and Eleanor (Schifferdecker) Wolff, Roger arrived on April 10, 1911. The family resided in the rural farm community of Evansville, Illinois, south of St. Louis. Census information from 1930 traced the Wolff family lineage back to France. As one might surmise from the German name, Leo’s father was born in the Alsace region.

A skilled butcher by trade, Leo Wolff took advantage of an opportunity to become the proprietor of a small grocery store in nearby Chester, Illinois. Thus, the family relocated in 1922. The hard-working patriarch involved all ten children in the family business, with young Roger becoming a skilled butcher in his own right.2

Wolff started throwing the knuckler as a little boy, and because his hands were so small then, he used a three-fingered grip. He threw it that way ever after, even though it was unorthodox.3 Infrequent work breaks might find Roger playing catch with one of his brothers, in a vacant lot next to the store. Already experimenting with trick pitches, Roger delighted in making each offering increasingly difficult for his sibling to handle.4

Wolff played baseball at Chester High School before dropping out in 1929. The decision was prompted by an opportunity to play independent ball in another nearby town, Red Bud, Illinois. Manager Red Burgdorf was also an unofficial scout for the St. Louis Cardinals. Watching young Roger in action, Burgdorf alerted Branch Rickey to Wolff’s potential; the tip led to a contract.5

The prospect reported to Danville, Illinois in 1930, going 4-5 with a 4.98 ERA in the Three-I League (Class B). It was the start of an arduous 12-season trek through the hinterlands of the lower minor leagues in Depression-era America.

The young Wolff reportedly had a dazzling fastball. His catchers were also loath to handle his knuckler and talked him out of throwing it. Rickey, however, ordered Wolff to keep working on it.6

After the season ended, Wolff returned to Chester to help his father at the family market, On the side, he pitched with the Southern Illinois Penitentiary team (the prison was located in the same town). That squad beat Max Carey’s All-Stars in one match. Wolff hastened to add, “I got out of the prison immediately after the game.”7

Assigned to the Mississippi Valley League (Class D) in 1931, Wolff’s 15-9 record led the Keokuk Indians to a first-place finish. During the tough economic times, teams (or even leagues) regularly folded. Wolff saw action with four different clubs in 1932; his itinerary ranged from Single-A Denver (where his knuckler wouldn’t break in the thin air) to AA Indianapolis, before wrapping up in Class B with Springfield and Terre Haute. Wolff’s combined season record was 5-5 in 20 games.

His 1933 assignments included a 1-1 mark in Class A with Fort Worth, followed by an 8-7 record at Class C Dayton. Returning to Dayton in 1934, Wolff improved significantly to 17-12, accompanied by a 3.84 ERA. Wearing the Dayton uniform again in 1935, Wolff finished 14-14, 3.42.

A 1936 stint with Davenport in the Western League (Single A) produced an 8-6 record with a stingy 2.31 ERA. Moving to Oklahoma City in the Texas League, Wolff finished the season 3-7, 4.08. The 1936 season was his third in the Brooklyn Dodgers organization.

In 1937, Wolff made stops with four teams in three different leagues, with a collective record of 9-11 and a 3.97 ERA. That year he was a Detroit Tigers farmhand.

Wolff finished 1938 at 16-11 with a 2.87 ERA, pitching for Cedar Rapids, back in the Three-I league. Returning to Cedar Rapids in 1939, he compiled a fine 15-5 mark with a 3.08 ERA. The Raiders had become an affiliate of the Cleveland Indians that year after being in the Cardinals chain in 1938.

Wolff wed Mary Rose Montroy, his hometown sweetheart, on November 23, 1939. He later commented how marriage helped mature him into a more serious ballplayer.8

After 10 years in Organized Baseball, Wolff finally rated a picture in The Sporting News in its issue of January 18, 1940. The article noted, “Roger is a workhorse who not only takes his regular turn but also serves frequently in relief. His chief asset is a finger-tip knuckler which sails sharply. He’s a difficult thrower to catch and lost one game last season when his catcher missed a third strike, enabling a runner to score from third. He also has a good fast ball, a sweeping curve and plenty of mound craft.”9

Wolff had signed a contract with the Williamsport Grays, a farm team of the Philadelphia Athletics in the Eastern League (Class A). His productive season (10-6, 2.80) quietly caught the attention of loop president Tommy Richardson, on the lookout for talented players. Richardson had been a close friend of A’s owner-manager Connie Mack since the early 1920s.10

Returning to Williamsport in 1941, Wolff improved to 16-9, 2.66. Richardson now proactively recommended the knuckleball specialist to Mr. Mack. The introduction led to a contract with the big club.11

At age 30, Wolff made his major league debut on September 20, 1941 at Griffith Stadium in Washington. The right-hander pitched a gutsy three-hitter but lost the 1-0 duel to fellow knuckleballer (and future teammate) Dutch Leonard. Wolff also pitched a complete game in his other appearance that year but lost it too, giving up five runs, all earned. Yet he won praise: “That was the best knuckleball we’ve seen all summer,” said Lou Finney of the Red Sox.12

The Pearl Harbor attack on December 7, 1941, suddenly thrust the country into war. Washington owner Clark Griffith lobbied President Franklin Roosevelt, seeking a directive allowing baseball to continue. Roosevelt concurred: “I honestly feel it would be best for the country. . .Americans will need to take their minds off work even more than before.”13 He officially issued the “Green Light” letter on January 15, 1942, ensuring the continuation of baseball as essential to the morale of the country.

Rosters were systematically depleted during the 1942 season, as volunteers and drafted players left the diamond to serve in the military. Wolff, with bad feet and even worse teeth, was classified 4-F (unfit for active duty). He became a regular starter in 1942 for the last-place Athletics, going 12-15 with a 3.32 ERA.

Ahead of the 1943 season, Washington purchased left-handed knuckleballer Mickey Haefner from the Minneapolis Millers to team with Leonard. That August, the Nats acquired a third knuckleballer when Johnny Niggeling arrived from the St. Louis Browns. Washington catcher Jake Early viewed these acquisitions as additional opportunities to get beaten up behind the plate.14

Reading the tea leaves, Early speculated, “Suppose Mr. Griffith buys Roger Wolff from the Athletics? Then I’ll have all the top knucklers in captivity throwing at me. I promise you, if this club ever signs that Wolff, I’m either quitting or getting a raise.”15 Meanwhile, the A’s remained in the AL cellar. Wolff retained his regular spot in their rotation, also pitching 15 times in relief. He contributed a 10-15 record, with a 3.54 ERA.

After finishing seventh in 1942, Washington improved to second place in 1943. Thus, Griffith was cautiously optimistic going into the winter meetings in New York. Conferring with his friend Connie Mack on December 13, 1943, the owners agreed to swap starting pitchers. Griffith sent veteran Bobo Newsom to the A’s in an even-up deal for Wolff.

Red Sox player/manager Joe Cronin called Wolff’s knuckler “the best I ever saw.”16 Respected umpire Cal Hubbard considered it unique because it broke upward.17 Despite these accolades, Wolf was often dismayed, because many catchers hated to handle the dancing knuckler and could simply refuse to call for the pitch.

Jake Early drew his pay from Uncle Sam in 1944. He distinguished himself as part of an artillery unit, serving in Europe during the Battle of the Bulge. While Early served overseas, the Senators re-acquired Rick Ferrell from the Browns. Ferrell recalled to columnist Arthur Daley: “Every game was an adventure because our four best pitchers were knuckleballers. When they released the ball, they didn’t know where it was going and neither did I.”18

Hopes ran high for Washington as spring training 1944 got underway at the University of Maryland in College Park. Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis’s wartime edict, directing all teams to train close to home, remained in effect. The addition of Wolff to the pitching staff seemingly positioned the Senators as legitimate pennant contenders. Despite such optimism, Washington started badly and fell to last place by the end of the season.

The Senators played their final home game of 1944 on Saturday, September 16. Wolff pitched seven tough innings in an 11-5 loss to the Boston Red Sox. He ended 1944 at 4-15, with a 4.99 ERA. The downcast pitcher left the park that day thinking about the trade that brought him to Washington. Numbers don’t lie; he was certain that Clark Griffith considered the straight-up deal for Newsom a huge mistake. Wolff was so lost in regret he failed to notice a young fan by his side.

With ball and glove in hand, the boy stared up at the pitcher and politely requested an autograph. Wolff was amused, wondering why anyone would be interested in his signature after such a challenging season. He was further taken aback when the boy asked for instructions on how to throw a slider. The pitcher grinned and remarked, “My best ball is a knuckler.” Coach George Uhle had indeed taught Wolff to throw a slider, but he seldom used it.19

Despite not being in the mood, Wolff conducted an impromptu training session while playing catch. Lesson over, he thought about the exchange while en route to his automobile: “Nice kid, maybe he’s got something.”20 Mulling over the discussion, the six-foot hurler, who was listed at 208 pounds, became determined to lose weight and get into shape during the off-season, while practicing his slider.

When the Nats returned to the University of Maryland for spring training 1945, a fit and trim Roger Wolff arrived on the scene. He had lost 15 pounds on a vigorous training regimen. Wolff’s three-finger knuckler certainly remained his primary pitch but was accompanied by renewed confidence in his slider.

Before the start of the 1945 season, Clark Griffith granted early stadium access to the Washington Redskins football team. The decision compressed the baseball schedule, resulting in an inordinate number of September doubleheaders.21

The Senators utilized the Bethesda Naval Base as temporary housing, with limited workouts taking place on the premises. Griffith made a serious judgment error in his zeal to collect extra rent. By uprooting players from their accustomed home base, the move adversely affected a team that legitimately became a pennant contender.

Wolff finished 1945 at 20-10, pitching 21 complete games in 29 starts, with an impressive 2.12 ERA. Two of his ten losses (one in relief) were 1-0 ballgames. His effectiveness helped keep the club in the thick of a tight pennant race – up until the last day of the season. Wolff remarked, “We seemed to find ways to win ball games. And I was sure nobody could hit me when I pitched.”22 That season Rick Ferrell said, “I often wonder how Babe Ruth would hit some of the stuff that Wolff throws. Some nights, especially with a little wind against him, he’s really wicked.”23 And whereas previously big-league hitters feasted on Wolff’s fastball if he fell behind in the count with the knuckler, in 1945 he came back with a slider instead and got them out.24

Washington finished its 1945 schedule on September 23 with a record of 87-67. The Detroit Tigers were in first place at 86-64. After splitting a doubleheader, the Tigers needed one victory in their remaining two games against the St. Louis Browns. If Detroit lost both games, a single-game playoff against the Senators was scheduled in Detroit, on Monday, October 1. A washout in St. Louis on Saturday, September 29 forced a Sunday doubleheader on a rain-soaked field.

Anticipating the possible playoff, the Nats sent Wolff, Leonard, Niggeling, and Ferrell ahead to Detroit. The quartet huddled in the hotel, intently listening to the Sunday game on radio. The rain returned, but it didn’t deter Hank Greenberg from smacking a game-winning grand slam in the ninth inning of the opener, ending any speculation of a playoff. The disappointed Washington players packed their bags and caught the next train to DC.

Ahead of the 1946, wealthy Mexican baseball magnate Jorge Pasquel offered many players salaries well above the big-league norm to jump leagues and pitch south of the border. Representatives from the Mexican League contacted Wolff during the off-season, offering the pitcher $115,000. Wolff weighed the lucrative offer but eventually declined it to remain with Washington.25

In deference to Wolff’s 20-win season, manager Ossie Bluege named the 35-year-old righty his Opening Day starter for 1946. Post-war rosters began filling with players returning from military service, greatly improving the overall level of play. On April 16, as the Boston Red Sox faced the Senators in DC, Tex Hughson topped Wolff, 6-3. Wolff finished April with a 2-2 record but did not reach .500 again until early June, despite an ERA below 2.00. After that he won just one of his remaining five decisions.

On Thursday, July 4, in Washington, Wolff pitched the second game of a doubleheader against the New York Yankees. In the fourth inning, with one out and Joe DiMaggio on first, the Yankees’ Nick Etten hit a tapper fielded by first baseman Mickey Vernon. Vernon threw to shortstop Cecil Travis for a force-out at second, but Travis’ errant throw forced Wolff (covering first) to lean back awkwardly. The pitcher tripped over the base, injuring his back.

Ray Scarborough replaced the hurting knuckleballer in the fifth inning. The Nats ultimately lost, 5-0. Wolff was sent to be examined by Griffith’s personal physician, who advised the pitcher not to throw under any circumstances. Griffith disagreed with the prognosis, insisting that Wolff play through the injury. He next appeared on July 19 against Detroit, pitching two innings in relief.

At the time, Wolff was approaching the five-year mark of his major-league career, then the minimum amount of time in service needed to qualify for a pension. Not willing to jeopardize his retirement, he acquiesced to Griffith’s orders, boarding a Cleveland-bound train on July 25 to join his teammates.

Griffith phoned Bluege, ordering his manager to have Wolff pitch batting practice. Bluege complied, and following the workout, Wolff returned to the hotel in excruciating pain. He was barely able to get out of bed the next morning.

Wolff arrived at the ballpark and discussed the situation with Bluege. A decision was made to see Dr. Robert Hyland, the highly regarded team physician of the Cardinals and Browns, known and trusted by both the player and manager.26 Following that exam in St. Louis, Wolff was advised that he’d suffered a serious muscle tear and instructed not to pick up a baseball, again (ostensibly) under any circumstances.27

Yet Griffith once more countermanded the doctor’s orders, insisting that Wolff continue to pitch through the pain. He was able to appear just once in August and twice in September. With a complete-game victory in his last outing, he finished the season at 5-8, with a respectable 2.58 ERA. Washington ended the season in fourth place at 76-78.

The Nats traded Wolff to the Cleveland Indians on March 4, 1947, in a deal that returned speedy outfielder George Case to Washington. In seven games with Cleveland, Wolff recorded no decisions, while posting a 3.94 ERA in 16 innings. The Tribe sold the knuckleballer’s contract to the Pittsburgh Pirates on June 15, 1947; he went 1-4 in 13 games with a bloated 8.70 ERA.

After the season, Pittsburgh released Wolff to Sacramento in the Pacific Coast League, but he chose instead to retire. He finished his big-league career with an overall record of 52-69, and a 3.41 ERA.

After leaving baseball, Wolff worked as a food broker, sold insurance, and ran a nightclub. He then landed a long-term position as Athletic Director at Southern Illinois Penitentiary (which became known in 1970 as Menard Correctional Center).

Invited to participate in numerous old-timers’ games, Wolff decided not to participate in view of his weight (approaching 250 pounds) plus the foot issues from his playing days. He commented, “I’m not gonna get out there and make a fool of myself at my age and condition.”28 Another factor was lingering after-effects from his back injury.

Mary Rose Wolff passed away on February 16, 1981; the couple had no children. Roger Wolff was a resident at St. Ann’s Healthcare Center in Chester when he passed away on March 23, 1994, just shy of his 83rd birthday.

How good was Roger Wolff’s knuckleball? He recalled an incident on a long-ago train ride. “I was sitting by myself in the dining car and Ted Williams comes in, and he plops down. Williams remarks: “Goddam, I can’t hit you. I can hit Leonard and Niggeling, but I can’t hit you.”29

Acknowledgements

Thanks to the National Baseball Hall of Fame, for sharing the content of Wolff’s player file.

This biography was edited by Rory Costello and fact-checked by David Kritzler.

Additional Sources

Online

Ancestry.com

Finadagrave.com

Notes

1 The team’s official name was the Washington Nationals, and thus they were often known as the Nats.

2 Red Smith, “Nats Net Butterfly-Ball Roger Wolff, Who Rambled to Majors on Knuckles,” The Sporting News, December 23, 1943, 7.

3 J.G. Taylor Spink, “From Woeful Wolff to Jolly Roger,” The Sporting News, August 16, 1945, 2.

4 Michael Fedo, One Shining Season (New York: Pharos Books, 1991), 6.

5 Smith. “Nats Net Butterfly-Ball Roger Wolff.”

6 Ibid.

7 L.H. Addington, “In the Bullpen,” The Sporting News, October 30, 1930, 7.

8 Smith. “Nats Net Butterfly-Ball Roger Wolff.”

9 “Raiders in Front Ranks,” The Sporting News, January 18, 1940, 7.

10 “Tommy Richardson Inducted into Bowman Field Hall of Fame,” MILB.com, January 15, 2009 (http://www.milb.com/gen/articles/printer_friendly/clubs/t449/y2009/m04/d07/c551902.jsp)

11 Spink, “From Woeful Wolff to Jolly Roger.”

12 Smith. “Nats Net Butterfly-Ball Roger Wolff.”

13 Ted Leavengood, Clark Griffith, The Old Fox of Washington Baseball (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2011), 258-259.

14 Shirley Povich, “This Morning,” The Washington Post, December 15, 1943.

15 Shirley Povich, “This Morning,” The Washington Post, August 23, 1943.

16 Shirley Povich, “This Morning,” The Washington Post, December 15, 1943.

17 “The Old Scout,” clipping from Hall of Fame file, May 1943 (no other identifying information is available).

18 Arthur Daley, “The Man in the Iron Mask,” The New York Times, June 22, 1944.

19 Spink, “From Woeful Wolff to Jolly Roger.”

20 Ibid.

21 Ted Leavengood, Clark Griffith, The Old Fox of Washington Baseball (North Carolina: McFarland, 2011), 264.

22 Fedo, 10.

23 Frank (Buck) O’Neill, “Weaker Hitters Best Against Knuckleballers,” The Sporting News, June 14, 1945, 7.

24 Spink, “From Woeful Wolff to Jolly Roger.”

25 “Mexican League Offer,” Tennessee Kingsport News, March 13, 1946, 2.

26 “Dr. Robert Hyland, Baseball Surgeon,” New York Times, December 15, 1950, 31.

27 Fedo, 11-13.

28 Fedo, 3.

29 Fedo, 1. Indeed, Williams was just 6-for-33 (.182) against Wolff in his career, whereas he was 12-for-38 (.316) against Leonard and 16-for-40 (.400) against Niggeling.

Full Name

Roger Francis Wolff

Born

April 10, 1911 at Evansville, IL (USA)

Died

March 23, 1994 at Chester, IL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.