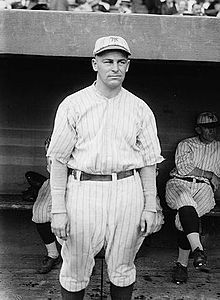

Ross Youngs

It is an oft-told story that legendary manager John McGraw, who led the New York Giants for 30 eventful years, had photographs of only two former players on his office wall: Christy Mathewson and Ross Youngs, today an almost forgotten Hall of Fame outfielder.1 Youngs personified the type of all-out hustle and will-to-win ballplayer that McGraw loved and combined that attitude with consummate skill as a ballplayer. Youngs could hit, run, field, and throw with the best who have played the game. But his is one of baseball’s tragic stories. Felled by a fatal kidney disease in the prime of his baseball career, Youngs was only 30 years old when he died in 1927. In ten years in the major leagues, only seven complete years of which he was fully healthy, Youngs compiled a .322 batting average and played on four pennant winners and two World Series championship teams.

It is an oft-told story that legendary manager John McGraw, who led the New York Giants for 30 eventful years, had photographs of only two former players on his office wall: Christy Mathewson and Ross Youngs, today an almost forgotten Hall of Fame outfielder.1 Youngs personified the type of all-out hustle and will-to-win ballplayer that McGraw loved and combined that attitude with consummate skill as a ballplayer. Youngs could hit, run, field, and throw with the best who have played the game. But his is one of baseball’s tragic stories. Felled by a fatal kidney disease in the prime of his baseball career, Youngs was only 30 years old when he died in 1927. In ten years in the major leagues, only seven complete years of which he was fully healthy, Youngs compiled a .322 batting average and played on four pennant winners and two World Series championship teams.

Ross Middlebrook Youngs was born on April 10, 1897, in Shiner, Texas, the second of three sons born to Stonewall Jackson (Jack) Youngs and Henrie (Middlebrook) Youngs.2 His father was a maintenance supervisor for the San Antonio and Aransas Pass Railroad until a track accident left him unable to continue to work for the railroad. His parents then ran a trackside hotel until they moved the family to San Antonio in 1907 when Ross was ten years old. His father subsequently left the family, leaving Henrie to soldier on to support her three sons by herself. As a result, Ross Youngs became very close to his mother; even after he became a well-known major league ballplayer he would return home and live with her in the off-season.3

In a grammar school track meet Ross flashed the speed that he would eventually take to the major leagues, winning all the sprints, the broad [long] jump, anchoring the winning 440-yard relay, and scoring 23 of the 54 points for his school.4 During the summers he helped the family make ends meet by selling sodas and renting seat cushions to fans attending the San Antonio Bronchos’ Texas League games. He got to know the manager and the players and sometimes took infield practice with the team at his favorite position, second base. In 1913, with the Bronchos far out of the pennant race, manager George Stinson played the 16-year-old Youngs at second base in a regular season game. He went 0 for 3 but the local newspaper made note of his promise.5

Ross had played baseball as a reserve that spring for San Antonio High School where his older brother Arthur was a star for a team that defeated all comers. Although only 5’6” and perhaps 140 pounds, he played high school football that fall. As the season wore on, he became the star running back, even achieving a rare 100-yard rushing game against Southwest Texas Normal in a 32-14 loss.6

In January 1914 Youngs transferred to the Marshall Training School, a vocational school for boys run by the Episcopal Church. He joined the school’s basketball team, which won the Southwest Texas Academy Athletic League Championship. He also was on the school’s baseball team for a time, although it is unclear what role he played or if he even played the entire season.7

That summer Youngs apparently continued to hang around the Bronchos ballpark but the team did not sign him. Instead, the Austin Senators gave the 17-year-old a shot and on August 1 he played shortstop in both games of a doubleheader for the Senators against the Bronchos in Block Stadium. Youngs went 1 for 4 with two runs scored in the first game and 3 for 4 with three runs scored in the nightcap as the Senators won both games. It was a high point of a dismal season for Austin, which set a Texas League record for futility with a 1914 season record of 31 wins and 114 losses. Youngs, who didn’t appear in a game after August 12, experienced his own futility, finishing with eight hits in 55 at bats for a .145 batting average. He had only one extra base hit, a double against San Antonio on August 11.8

That fall Youngs enrolled in the West Texas Military Academy in San Antonio. The Academy was known for its prowess in sports and may have recruited Youngs to play on the football team. Play he did, scoring in every game and leading the team to a 6-2 record with several long touchdown runs along with an 80-yard punt return for the only points in a 6-0 win against a team from Fort Sam Houston. The rival Peacock Military Academy refused to play WTMA for the city championship because of Youngs’s professional baseball stint that summer.9

In the winter Youngs played on the school’s basketball team, once scoring 18 of its 24 points in a 24-14 victory over San Antonio Academy. He did not play baseball for WTMA, however, because he was instead recruited to play for the Bartlett Cotton Kings in the Class D Middle Texas League. Unfortunately, the league folded on June 19 but there was time enough for Youngs to flash some potential. In 59 games he batted .264 with 25 stolen bases and eleven doubles. That showing was enough to get him picked up by Waxahachie of the Central Texas League, also a Class D organization. But in late July after Youngs appeared in 25 games and hit .274 with 16 stolen bases, that league folded as well.10

He then headed east to play for Lufkin in the semi-pro East Texas League where he was noticed by Roy Aiken and Walter Salem, scouts for the Houston Buffs of the Texas League. Upon their recommendation, Buffs general manager Doak Roberts offered Youngs a contract. He was to report when Lufkin’s season was over, but on August 16, 1915, a devastating hurricane hit Galveston and Houston. Rather than report to the Buffs, who had to play their remaining games on the road, Youngs traveled home to San Antonio to get ready for his senior year of high school.11

He once again starred on the gridiron, leading WTMA to a second straight city championship while scoring almost half of their 149 points on runs, punt returns, or interception returns. Although he likely would have been an outstanding college football player and reportedly turned down several college scholarship offers, he had his sights on professional baseball. Joe Straus, who starred at rival San Antonio High and went on to become an All-American at the University of Pennsylvania, later told New York sportswriter Frank Graham that “he was so much better than I was that if he had gone to Penn with me, you’d never have heard of me.”12

In the spring of 1916, the Houston Buffs farmed the 19-year-old Youngs out to the Sherman Lions in the Class D Western Association, an eight-team league with teams in North Texas, Western Arkansas, and Oklahoma. Playing second base and some shortstop, Youngs started strong and never slowed down. In 137 games he led the league in batting (.362), hits (195), and runs (103). He stroked 30 doubles and six triples and stole 42 bases. During a hot streak in the middle of July he went 31 for 48, an amazing .646 batting average. Even with his fine bat, Youngs was erratic in the infield, committing as many as four errors in a game; as the season wore on he began splitting time between center field and shortstop.13

Late in the season, Lions manager Walter Franz wrote New York Giants manager John McGraw about Youngs, prompting McGraw to send his chief scout Dick Kinsella to check him out. Kinsella’s recommendation was reportedly, “Grab him.”14 Youngs favored the Detroit Tigers, who had also expressed interest, because he thought it would be easier to crack the Tigers outfield than that of the Giants, but Sherman sold his rights to McGraw for $2,000.15

The 5’8’’, 160-pound Youngs was not yet 20 when he reported to the Giants’ 1917 spring training site in nearby Marlin, Texas.16 He made an immediate impression on McGraw with his hustle and desire, so much so that McGraw began referring to him as “Pep,” a name that stuck with Youngs for his career.17 Youngs fancied himself a third baseman by now, but McGraw soon realized that Youngs was not cut out to be an infielder; near the end of spring training he sent him to the Rochester Hustlers in the International League to convert to the outfield.18 McGraw allegedly told Rochester manager Mickey Doolan, “I’m going to give you a kid who is going to be a great ballplayer. Take good care of him, because If anything happens to him, I’ll hold you responsible.”19

The Class AA International League was one step from the majors and a huge jump from Class D. Doolan must have done a pretty good job with Youngs because the youngster hit .356 in 140 games for the Hustlers, second in the league.20 His performance earned him a September call-up from the Giants, who clinched the pennant in the middle of the month.21 Youngs made his big-league debut on September 25 against the Cardinals in St. Louis, leading off and playing center field. He went 0 for 4 against Marv Goodwin in a 5-3 loss. He also went 0 for 4 with a walk the following day in a 12-inning loss before hitting a single and a triple on September 29 in Cincinnati against the Reds’ Mike Regan for his first major league hits in a 4-2 Giants win. In all, he appeared in seven games for the Giants at the tail-end of 1917, collecting nine hits in 26 at bats for a .346 average. He finished the regular season with a promise of what was to come, going 3 for 4 with a double and two triples in a 6-0 victory over the Phillies in Philadelphia.22

The Giants went on to lose the World Series to the Chicago White Sox, four games to two, as Youngs, who was not eligible for the post-season, watched from the bench. After the season McGraw was uncharacteristically effusive in his praise of Youngs, saying “Young [sic] shows more enthusiasm and real talent than any youngster who has broken into the game in fifteen years.”23

The Giants moved their spring training base to San Antonio in 1918 and Youngs hit well from the beginning of camp. McGraw made it clear early on that Youngs was to be his right fielder, even over the incumbent Davy Robertson, who had in any event failed to report.24 The Giants got off to a blazing 18-1 start once the season began as Youngs became a fixture in right-field. He put together a league-best 23-game hitting streak in July and finished with a .302 batting average, one of just six regulars to hit above .300 in the National League. The Giants, however, played only .500 ball after their fast start and finished second, 10 ½ games behind the Chicago Cubs in the war-shortened season.

The Giants trained in Gainesville, Florida, in 1919. There McGraw convinced Youngs, who had always been a switch hitter, to bat only from the left side to take better advantage of his great speed.25 The team got off to another fast start, winning 24 of their first 32 games. Youngs, who was now batting second in the line-up behind George Burns, was also blistering hot out of the gate, and on May 31 was batting .407 after reaching .488 ten games into the season. His all-around play began drawing comparisons with Ty Cobb at a similar age, and he was even called “Ty Cobb Junior.”26

Youngs cooled off in the second half of the season, even dipping below .300 in August before rebounding to finish with a .311 batting average, third best in the league, in 561 plate appearances while leading the league with 31 doubles. In a season shortened to 140 games coming out of World War I, the Giants put together an impressive .621 winning percentage with an 87-53 record. They still finished nine games behind the Cincinnati Reds, who went 96-44. At the end of the season, the Giants barnstormed through Canada, netting Youngs and his teammates some additional income.27

Rumors swirled in the offseason that the champion Reds were offering star center fielder Edd Roush straight up in a trade for Youngs. McGraw countered that he would only consider it if the Reds included starting shortstop Larry Kopf in the deal, and the Reds declined. At the time the 26-year-old Roush was in the prime of a Hall of Fame career with two batting titles already to his credit, but McGraw made it clear upon arriving at spring training in San Antonio that he would not trade Roush for Youngs even up.28Youngs got off to a slow start in 1920, but on May 11 he set a major league record with three triples in a game against the Reds in Cincinnati. He caught fire as the season wore on and hit .392 for August, including a five-hit game in a 17-inning 6-4 win over the Reds on August 27. He finished the season at .351, second highest in the league.29 His 204 hits were tied for second; he was third in slugging percentage (.477) and total bases (277) as he established himself as an elite player. Youngs also made spectacular plays in the field and exhibited an exceptional throwing arm, leading the league in outfield assists for the second year in a row with 26.30 The Giants, however, were bridesmaids again, finishing in second place, seven games behind the Brooklyn Robins.

McGraw thought so much of Youngs that he signed him to a three-year contract at $12,000 a year in the offseason, an amount higher than Youngs had requested.31 Near the end of spring training, however, Youngs banged up a knee in a home plate collision and was forced to miss the first two weeks of the season. He then got off to a somewhat slow start before catching fire in June. He hit .442 for the month, bringing his season average up to .372 as he helped the Giants keep within shouting distance of the league-leading Pirates.

By July 30 the Giants had pulled even with the Pirates and were playing the Reds in a doubleheader in Cincinnati. They lost the first game, 8-1, and between games Youngs was involved in a dugout fight with teammate Fred Toney, who had pitched poorly and taken the loss in the first game. Apparently, Toney made a caustic comment to Youngs, who had battled the sun in right field, about his fielding. Youngs, five inches shorter and 30 pounds lighter, responded with a remark about Toney’s shoddy pitching and then threw a punch. The fight spread onto the field in front of the dugout before teammates separated the two.32

Internal strife notwithstanding, the Giants, aided by newcomer Irish Meusel and the development of Frankie Frisch and George “High Pockets” Kelly, won the 1921 pennant by four games after falling 7 ½ games off the pace in late August. Youngs finished with a .327 batting average in 141 games. Before the season, McGraw had moved Youngs into the clean-up slot in the batting order and he responded by driving in a career high 102 runs, tied for third in the league.

The Giants’ National League pennant set up a much-anticipated World Series match-up against the New York Yankees, who also played at the Polo Grounds. Babe Ruth had had a gargantuan season with the Yankees, batting .378 and hitting an almost unimaginable 59 home runs while driving in 170. As a result, the Series was a match-up of styles, McGraw’s old deadball era style of contact-hitting, hit and run, and aggressive base-running to squeeze runs across versus the Yankees’ power game.

In the last year of the best-of-nine game format, the Yankees shut out the Giants in the first two games, as Youngs went hitless. But in the seventh inning of the third game, Youngs doubled and then smashed a three-run triple as the Giants erupted for eight runs to break up a tie game which they eventually won, 13-5.33 Youngs was the first in Series history with two hits — two extra base hits –in an inning. His five total bases were also a record.

The Giants went on to take the Series in eight games. Youngs batted .280, but drew seven walks and had an on base percentage of .438. He also contributed defensively, making a spectacular running catch of a deep drive by Elmer Miller in Game Six.

Youngs got off to another slow start in 1922 but came alive on April 29 against the Boston Braves in Boston. That afternoon against starter Dana Fillingim and reliever Rube Marquard, he went 5 for 5 and hit for the cycle with an inside-the-park home run, a triple, two doubles and a single in leading the Giants to a 15-4 victory. It was the only cycle of Youngs’s brief career, but one of four five-hit games.34 That performance got the 25-year-old back on track and he finished the season with a .331 batting average and 86 runs batted in as the Giants won their second consecutive pennant by seven games over the Cincinnati Reds. He also led the league in outfield assists for the third time with 28.

The Giants again faced the Yankees in the World Series, which reverted to the best-of-seven format. This time McGraw’s boys swept their counterparts in four close games, with a fifth game (Game 2) ending in a 3-3 tie because of darkness. Youngs hit .375 for the Series and drove in the winning run in Game 4, a 4-3 Giants win. Some believe that the 1922 Giants, who hit .305 as a team, swept the Yankees, and featured Youngs plus four other Hall-of-Famers, was the greatest Giants team of all time.35

Youngs had another outstanding year in 1923, hitting .336 in 152 games as the Giants swept to their third consecutive National League pennant. He totaled 200 hits and scored 121 runs to lead the league. By now he was universally regarded as the best right fielder in the senior circuit and drew comparisons of his overall value to a right fielder in the American League named Babe Ruth.36 Sportswriter Robert Boyd thought that Youngs was just as great a player as Ruth, Tris Speaker, Edd Roush, or Eddie Collins, although perhaps lacking their “color.”37

The Giants were derailed from their third straight World Series win by the Yankees, who had breezed to the American League pennant by 16 games. The Giants won two out of the first three games, but then the Yankees’ bats caught fire. They swept the final three games, scoring a total of 22 runs, to win the Series four games to two. Youngs batted .348 for the Series and had his career post-season game in Game 4, going 4 for 5 and smacking a ninth inning inside-the -park home run off Herb Pennock.

In the offseasons Youngs returned to San Antonio and did a lot of bird hunting and played a lot of golf. He was probably close to a scratch golfer and after the 1923 season made it to the semi-finals of the San Antonio City Championship.38

The 1924 season turned out to be a tumultuous one for Youngs, even as the Giants won their fourth consecutive pennant, narrowly beating out the Brooklyn Robins. On the field, he hit .356 in 612 plate appearances, the highest average of his career and third best in the league.39 He also stroked 33 doubles, 12 triples and a career high ten home runs. However, in late July he was stricken with what turned out to be strep throat and missed three weeks of the season. Although he hit well after his return, his throat continued to bother him, and he batted only .185 in the World Series, which the Giants lost in seven games to the Washington Senators and Walter Johnson.

Shortly before the Series began, Youngs was implicated in an ugly scandal involving an attempted late season bribery of Philadelphia Phillies shortstop Heine Sand. On September 27, Giants outfielder Jimmy O’Connell approached Sand and offered him $500 if he would “go easy” against the Giants in their season-ending two-game series.40 Sand immediately rejected the overture and reported it to Phillies manager Art Fletcher, who telephoned National League President John Heydler, who in turn called Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis. When Landis questioned O’Connell, he indicated Giants coach Cozy Dolan had put him up to it and implicated Youngs, Frankie Frisch, and George “High Pockets” Kelly. O’Connell’s story was that the idea was for the entire team to contribute towards the $500 and that he had discussed it with his three teammates, who agreed to the scheme.41

Landis, who was in New York, quickly summoned Youngs and his two teammates and interviewed them separately. All three denied O’Connell’s story, and since it was without corroboration, Landis exonerated them, telling veteran sportswriter Fred Lieb, “No court in the country would convict Frisch, Kelly, and Youngs on the evidence which was furnished me.”42

Earlier during the 1924 season Youngs had met Dorothy Peinecke, a young woman from Brooklyn, at a resort in the Berkshires. They began dating and when McGraw announced that he was taking the team on a post-season exhibition tour of Europe, Youngs wanted Dorothy to go with him. Although they had not known each other long, he persuaded her to marry him immediately after the season. Their wedding was originally scheduled for October 10 at St. Paul’s Methodist Episcopal Church in Brooklyn, but had to be postponed one day until October 11 because of the Seventh Game of the World Series.43

Youngs and his new bride, along with five other newlywed couples, accompanied the Giants and the Chicago White Sox on the European tour, which had mixed results. The teams played before King George V and Queen Mary before a crowd of about 10,000 in London, but reportedly drew only about 20 people for a game in Dublin on a cold and wet afternoon. When interest in Belfast and Paris was not much better, the tour was cut short, with McGraw reportedly losing $20,000 on the venture.44

After the abbreviated tour, the Youngs arrived in San Antonio on November 15 to spend the winter. Youngs was still not feeling well after the tour but hoped a return to San Antonio would get him back on track.45 However, Dorothy and Ross’s mother Henrie apparently did not get along and Dorothy did not return to San Antonio with her husband after the 1925 season. The couple’s only child, a daughter named Caroline, was born in December 1925 in Brooklyn. Youngs filed for divorce in San Antonio during the last months of his life in 1927, but he died before it was granted.46

Youngs, who turned 28 in April, continued to feel below par during spring training and for much of the 1925 season, struggling to a .264 average, the first time in his career he had hit below .300. His decline surely had something to do with the Giants sliding to second place, 8 ½ games behind the Pittsburgh Pirates, thus ending their consecutive National League pennant run at four.

Youngs still had plenty of fight left in him, however. On August 25, on a sweltering day in the Polo Grounds, Youngs collided with Reds pitcher Pete Donohue on a close play at first base, knocking the ball out of Donohue’s hand. On his next at bat, Donohue sailed a pitch by Youngs’s head and then hit him in his right elbow. Youngs charged the mound swinging and managed to break a finger in his right hand in the melee, putting him out of action for almost a month. He was also tossed from the game, as was Donohue, and fined $100.47

Youngs was still feeling weak and having stomach issues when he reported to spring training in Sarasota, Florida. before the 1926 season.48 Once the season began, doctors required Youngs to carefully manage his diet and McGraw went so far as to hire a male nurse to be with him both at home and away.49 Even so, Youngs managed to play in 95 games and bat .306 with 114 hits and 21 stolen bases. He missed several games in May but rebounded to hit .385 for the month of June, including a four-for-four day with two stolen bases against the Phillies on June 21.

Youngs also worked with a 17-year old Giants rookie named Met Ott, teaching him how to play the severe caroms of the Polo Grounds right field wall, which was only 259 feet down the line before jutting to a deep right-center field. Youngs was so accomplished at playing balls off that wall that Waite Hoyt said, “He played that carom as if he’d majored in billiards.”50 But poor health returned, and Youngs played his last game on August 10 before checking into New York’s Murray Hill Sanitarium with what was then reported as a severe cold.51

Youngs returned to San Antonio in October and in December was admitted to the Physicians and Surgeons Hospital there with what was termed the flu. He remained there until April when he improved enough to go home. He even expressed optimism about being able to rejoin the Giants. But he was unable to leave San Antonio and returned to the hospital in early October before passing away on October 22 from Bright’s Disease, or nephritis, a then-fatal kidney ailment.52

After his funeral service, a two-mile funeral procession followed his hearse to the Mission Park South Cemetery where he was buried. His estranged wife Dorothy and infant daughter Caroline, whom he had apparently never seen, were said to have traveled from New York to be at his graveside.53

The long funeral procession was a testament to Youngs’s popularity in his hometown and to the many friends he had, both inside and outside of baseball. He was generous and caring to a fault; it is said that at his death he was owed $16,000 by his many debtors. He did not smoke or drink; in addition to his love of hunting and fishing, he was by all counts the top golfer in major league baseball, sometimes betting $100 a hole at the San Antonio Country Club in offseason matches.54

Over the years, several theories emerged about how Youngs contracted the kidney ailment that killed him. His nephew, who was his namesake, said that Youngs would never drink water during a game because he was afraid it would slow him down and wondered if that might have injured his kidneys. Another theory was that Youngs may have injured his kidneys throwing so many cross-body blocks at second base to break up double plays.55

However, John McGraw biographer Charles Alexander interviewed Dr. Jesse H. DeLee of San Antonio, who had thoroughly investigated Youngs’s medical history. According to Dr. DeLee, a streptococcal throat condition (strep throat) migrated into his kidneys and resulted in a severe urinary tract infection.56 Before the advent of antibiotics, there was no effective treatment.

In 1936 the Baseball Writers of America voted to elect the first class for the new Hall of Fame that was to be established in Cooperstown, New York. Youngs finished 26th in the voting and thereafter received modest support, perhaps in part because of concern that he had not played the requisite ten major league seasons. Finally, in 1972, championed by former Commissioner Ford Frick and former teammates Frankie Frisch and Bill Terry, Youngs was unanimously elected to the Hall of Fame by the Veterans Committee.57

Although Youngs’s early death in what should have been the prime of his career has made him one of the lesser known Hall of Famers, those who played with and against him remembered him well. Long-time Giants traveling secretary Eddie Brannick selected Youngs as the right fielder on his all-time New York Giants team, ahead of Mel Ott. Twenty-five years after they were teammates, Rosy Ryan rated Youngs the best player he ever saw, ahead of Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig and the other stars of the 1920s. John McGraw of course agreed.58

Part of the acclaim was because of his defensive prowess. In a spring training game against the Chicago White Sox, he reportedly fielded a single to right field by Willie Kamm and rifled a throw home that trapped Earl Sheely, who was attempting to score from second base. Youngs sprinted in from the outfield to join in the rundown and ultimately tagged Sheely out, earning both an assist and a putout on the same play. According to his nephew, on another occasion he raced in and made a shoe-top catch of a Texas Leaguer and tagged out a runner between first and second for an unassisted double play.59

The winter after his death in 1927, the Giants decided to honor Youngs and Christy Mathewson, who was only 45 when he died in 1925 of tuberculosis, with memorial tablets to be placed on the outfield wall in the Polo Grounds. The idea was so popular that the Giants accepted donations, limited to $1 each, from fans. They came in from across the country, including $5 from inmates at Sing Sing Prison, where the Giants played an exhibition game each year. More than 100 donations came from former opponents, including Babe Ruth, who lamented that he wished he were allowed to give more. The plaques were unveiled between games of a doubleheader on September 27, 1928. At the ceremony, Youngs’s three-year-old daughter Caroline pulled the cord to unveil her father’s plaque.60

Noted sportswriter John Kieran, who had covered the Giants during their four straight pennants, was responsible for the eloquent inscription on Youngs’s tablet. He wrote:

A brave, untrammeled spirit of the diamond, who brought glory to himself and his team by his strong, aggressive, courageous play. He won the admiration of the nation’s fans, the love and esteem of his friends and teammates, and the respect of his opponents. He played the game.61

The plaques remained until the Giants left for San Francisco in 1958, but then disappeared and were not present when the expansion New York Mets moved into the Polo Grounds in 1962. According to Youngs’s biographer, they have never surfaced.62

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Norman Macht and fact-checked by Alan Cohen.

Notes

1 Joseph Durso, The Days of Mr. McGraw (New York: Prentice-Hall, 1969), 188-189; Frank Graham, “The Youngs McGraw Never Forgot,” Baseball Digest, February 1960:66; Frank Graham, The New York Giants (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1952, 211.

2 David King, Ross Youngs — In Search of a San Antonio Baseball Legend (Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2013), 18. Some record books incorrectly listed Youngs first name as “Royce,” but according to his brother Arthur D. Youngs it was always “Ross.” Correspondence dated March 31, 1972 between Clifford Kachline of the National Baseball Library and Arthur Youngs in the Ross Youngs clippings file, National Baseball Library, Cooperstown, New York. Noel Hynd, The Giants of the Polo Grounds (New York: Doubleday, 1988), 198.

3, King, 18-21.

4 He was also second in the pole vault. King, 12.

5 King, 22.

6 King, 23. Southwest Texas Normal is now Texas State University in San Marco, Texas.

7 King, 24.

8 King, 24-25.

9 West Texas claimed there were no rules against a professional from another sport playing football so long as he was enrolled, but the teams did not meet. King, 27.

10 King, 30-32.

11 King, 32.

12 Frank Graham, McGraw of the Giants (New York: GP Putnam’s Sons, 1944), 94.

13 King, 39-40.

14 King, 40.

15 F.C. Lane, “How Ross Youngs was Christened ‘Pep,’” Baseball Magazine, July 1923: 377. The Giants outfield at the time was made up of George Burns, Benny Kauff, and Davy Robertson.

16 The Giants held spring training in Marlin for eleven years altogether. It was then a resort town because of its hot springs, which many believed had a medicinal effect. King, 43-44.

17 Lane, 377.

18 “He fought the ball, fumbled it, threw wild to first base in his haste to get it away. . . He lacked the smoothness an infielder must have.” Graham, McGraw of the Giants, 94.

19 Graham, 94-95.

20 Youngs finished behind the 42-year-old Napoleon Lajoie, who batted .380 for Toronto.

21 According to one source, Youngs made a running catch of a deep flyball to right centerfield to help Rochester beat the Giants in an exhibition game and immediately joined the Giants as they headed west for a road trip. Charlie Vascellaro, “Unbridled — Forgotten Hall of Famer Ross Youngs Patrolled the Polo Grounds with Passion.” 108 Magazine, Summer 2007: 58.

22 All seven games were road games, so Youngs did not play at the Polo Grounds until 1918, his true rookie season.

23 King, 48.

24 McGraw had publicly criticized Robertson for a couple of misplays in the 1917 World Series, prompting Robertson to say that he would refuse to play for McGraw again. And he did not, instead joining the Secret Service before returning to baseball after he was traded to the Cubs in 1919. King, 52.

25 King, 62.

26 Lane, 377; King, 50-61.

27 Each player also received $800 for finishing second. King, 67.

28 King, 70-71; Lane, 378; Vascellero, 59.

29 Rogers Hornsby of the St. Louis Cardinals led the league with a .370 batting average.

30 King, 76.

31 In signing Youngs, McGraw called him “the ideal ballplayer” and praised his “spirit and willingness to do anything asked of him.” Lyle Spatz and Steve Steinberg, 1921 — the Yankees, the Giants, & the Battle for Baseball Supremacy in New York (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2010), 120; King, 79.

32 Of the two, Youngs was more eager to keep the fisticuffs going. Spatz and Steinberg, 287-88

33 The Giants recorded 20 hits in the game which is still a World Series record.

34 King, 91.

35 The other future Hall-of-Famers are Frankie Frisch, George Kelly, Dave Bancroft, and Casey Stengel, who was inducted as a manager. Hynd, 241.

36 Vascellaro, 60, 61; King, 102.

37 James Costello & Michael Santa Maria, In the Shadows of the Diamond: Hard Times in the National Pastime, (Dubuque, IA: Elysian Fields Press, 1992), 162-163.

38 King, 105-106.

39 Rogers Hornsby with a hard to believe .424 to lead the league. Brooklyn’s Zack Wheat was second with a .375 average.

40 The Giants were 1½ games in front of Brooklyn with two games to go.

41 David Pietrusza, Judge and Jury: The Life and Times of Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis (South Bend, IN: Diamond Communications, 1998), 263-266; J.G. Taylor Spink, Judge Landis and 25 Years of Baseball (St. Louis: The Sporting News Publishing Company, 1974), 117-120; Harold Seymour, Baseball: The Golden Age (New York: Oxford University Press, 1971), 378-379; Hynd, 254-56; Graham, The New York Giants, 153-157.

42 Landis did ban the 23-year-old O’Connell and the 34-year-old Dolan from Organized Baseball for life. In their interviews with Landis, Youngs and Frisch both acknowledged that sometimes there was kidding or talk about paying bribes but denied talking to O’Connell about any illicit payments. Youngs told Landis, “I have heard talking around and such things mentioning it, but I don’t remember who by. You hear fellows talking around that boys are offering money and something like that. I never heard anything like this, offering money here. This is the first I heard of it. . . . Cozy might have been talking or something like that, but as far as offering money, or something like that, no.” Pietrusza, 268.

43 King, 109.

44 Charles C. Alexander, John McGraw (New York: Viking Press, 1988), 265-266; Graham, McGraw of the Giants, 188-189; King, 109-110.

45 Graham, McGraw of the Giants, 203.

46 King, 110-111, 125.

47 King, 120.

48 Graham, McGraw of the Giants, 203-204.

49 King, 124, Graham, McGraw of the Giants, 208-209.

50 Sam Blair, “Forgotten Tragedy: The Saga of Ross ‘Pep’ Youngs — 1920s Baseball Star’s Career Often Overlooked,” Seattle Times, May 3, 1992

51 King, 125.

52 King, 125-131.

53 Some sources indicate that Youngs never saw his daughter, who was born in Brooklyn in December 1925. Since Youngs played for the Giants in 1926 in New York, it certainly seems possible that he did meet his daughter, even though separated from his wife. Blair.

54 Blair.

55 Bob Broeg, “Pep Youngs Flashy as Frisch on Basepaths,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch. February 1, 1972; Blair.

56 Alexander, 255, n. 29, 335; Blair.

57 The committee decided that since Youngs appeared in seven games in 1917 for the Giants, he met the ten-year minimum. Jack Lang, “Gomez, Youngs, Harridge Join Elite in Hall of Fame,” (unidentified clipping dated February 12, 1972 in the Ross Youngs file of Baseball Hall of Fame Library).

58 King, 65-66.

59 Blair.

60 King, 134-135; Blair.

61 Vascellaro, 63; King, 135.

62 King, 136.

Full Name

Ross Middlebrook Youngs

Born

April 10, 1897 at Shiner, TX (USA)

Died

October 22, 1927 at San Antonio, TX (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.