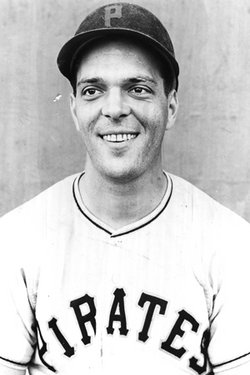

Sonny Senerchia

The answer to that long-fought debate as to which baseball player was the best violinist of all time is Sonny Senerchia, who appeared in 29 games with the 1952 Pittsburgh Pirates. Perhaps his toughest competition was Eddie Basinski, a violinist with the Buffalo Symphony Orchestra, who played with the Pirates in 1947.1

The answer to that long-fought debate as to which baseball player was the best violinist of all time is Sonny Senerchia, who appeared in 29 games with the 1952 Pittsburgh Pirates. Perhaps his toughest competition was Eddie Basinski, a violinist with the Buffalo Symphony Orchestra, who played with the Pirates in 1947.1

Emanuel Robert Senerchia arrived on April 6, 1929, in Newark, New Jersey, the second child born to Ralph and Lucy (Denofri) Senerchia.2 He was destined to follow in the footsteps of his grandfather and father, both of whom were accomplished musicians and concert violinists. His grandfather, also named Emanuel, was a maestro at the Milan (Italy) School of Music; an uncle was a successful composer (three other uncles were also musicians); and his father, Ralph, was a violinist with the Andre Kostelanetz Orchestra at the time Sonny made it to the Pittsburgh Pirates as a third baseman.3 Sonny started learning from his father at the age of 5, and by 10 he was good enough to perform at Carnegie Hall. He studied under Maximilian Pilzer, the former concertmaster of the New York Philharmonic. In time, Sonny would be named a member of the National Youth Symphony Orchestra – at the age of 12.4

About that time, Manny (as he was called by his family) discovered sports. At Barringer High School, he earned three letters playing football (quarterback and punter) and two more playing baseball (shortstop and pitcher). Barringer won the Newark City League football title in 1946, a season that saw only one loss. As a senior, Senerchia was named to the All-City 11. However, baseball was becoming as important to Sonny as the violin.5

Senerchia said his parents didn’t understand baseball. In 1952, when they saw Sonny homer off Hoyt Wilhelm in the Polo Grounds, they didn’t know why people were screaming or applauding, or even why he had to run around and touch all the bases. “My father,” he told an Asbury Park Press reporter, “had only one idea: he wanted me to become a concert violinist, like himself. And until I got to high school, I wanted it, too. I really loved it. When I quit playing the violin to concentrate on sports, he told my mother I took 10 years off his life.” Eventually, they came to understand and appreciate their son’s love of baseball.6

Immediately after graduating from high school, Senerchia played for Auburn of the Border League in 1948, one of a handful of players who found time at third base. The following season, Senerchia was a regular with Lima in in the Ohio-Indiana League, alternating between shortstop and third base and, on the last day of the season, pitching in relief. He wasn’t Emanual or Manny Senerchia then – he played ball under the name Bob Senerchia.7 After two seasons in low-level minor leagues, Senerchia gave up professional baseball to attend college.

Senerchia played baseball at Montclair State College for three years under coach Bill Dioguardi. Senerchia contributed at third base, the outfield, and on the mound for a team that once went 23-2, including victories over nearby schools St. John’s, Fordham, Long Island University, CCNY, Rider, and Upsala. During the summers, Dioguardi helped Senerchia get an opportunity to play amateur ball with Keene, New Hampshire, in the Northern League for two seasons.8

Things changed for Senerchia during his junior year at Montclair. A former Auburn teammate, pitcher Ike Delock, signed with the Boston Red Sox and described to him what being a major league player was like. “It sounded pretty good,” Senerchia recalled. “In fact, it was too good to pass up. My love for baseball was second only to the violin.”9

Scouts from the majors watched the hustling infielder with a strong throwing arm and a good deal of natural power. Branch Rickey, then the general manager of the Pirates, made him the best offer – a $10,000 signing bonus. So Sonny signed a contract with the Pittsburgh Pirates in 1952. He also received offers from the Chicago White Sox, the New York Giants, and Brooklyn Dodgers.10

Senerchia’s earnest and hustling play got attention from the writers, fans, and Pittsburgh brass. Sent initially to a Class B (Carolina League) team in Burlington, North Carolina, he established himself quickly as a legitimate prospect. The Burlington Daily Times-News wrote:

“Senerchia, top hitter on the club, was regarded by officials of the circuit and fans as one of the finest third basemen in the league and one of the top prospects on the club. He was the only Bur-Gra [Burlington-Graham] batter hitting over .300 and was by far the most popular player on the club from the fans’ standpoint. The youthful infielder had a brilliant fielding record. His arm was regarded as one of the best in the circuit and at the plate he revealed terrific wrist power.”11

At the end of the season, Richard Minor of the Times-News wrote:

“Awarding of Bur-Gra’s ‘most popular player’ prize, a valuable watch, to Sonny Senerchia should go down as a lesson to other players on the importance of doing their best at all times, even on a losing club. … [He] turned out to be a real spark plug, played that base like a veteran, and batted well enough to earn a promotion all the way to Pittsburgh, where he is doing a fine job at third base. … Senerchia won out because he played every night, and added fire to a club that was largely dead on its feet much of the time. Senerchia will probably land back in the minor leagues somewhere next year, and if that is the case he will find a warm welcome awaiting him in Burlington and Graham.”12

Senerchia wasn’t around to collect his watch. He had already been called up to the majors. (It was mailed to him.)

In 1952 the Pirates weren’t very good. Ralph Kiner was banging out homers and Joe Garagiola was honing his storytelling skills, but with a team about to fall 50 games below .500, Rickey brought up all of his prospects to see who might stick. Young players like Dick Groat, Ron Necciai, Lee Walls, and Sonny Senerchia were put in the lineup and told to do their best.

In fact, Necciai – famous for a 27-strikeout game in the minors – got his only win in the majors thanks to homers by Kiner and Senerchia, his first major-league shot. It came in the first game of a doubleheader against the Boston Braves. Speaking of future broadcasters (in addition to Garagiola, Kiner spent decades with the Mets and Groat later called college basketball games for the University of Pittsburgh), Senerchia’s first home run came off future Braves play-by-play man Ernie Johnson.13 By the end of the season, Senerchia had three homers among 22 hits in his 100 major-league at-bats – and 21 strikeouts. The high strikeout count belied his first impressions, told to Les Biederman of the Pittsburgh Press. “In the minors, the pitchers try to strike out every batter and they’re plenty wild,” Sonny said. “But up here they shoot for the corners and try to make you hit the ball somewhere.”14

Sent back to the minors for the 1953 season, Senerchia played well at Double-A New Orleans but wound up taking a tour of Class B-level cities, including Waco and a return trip to Burlington-Graham. He finished strong, though, earning the attention of the St. Louis Cardinals. The Cardinals selected Senerchia in the minor-league draft and assigned him to Houston of the Double-A Texas League.15 There, Senerchia started off well during spring training; on the heels of a hot homer streak, he felt sure he was going back to the major leagues soon when disaster struck.

In a spring-training game, Burlington pitcher Don Watkins fired a ball that hit Senerchia on his unprotected forehead. The pitch knocked Senerchia out cold – he was unconscious for nearly an hour and groggy for a couple of days. Fortunately, he survived without any fractures or apparent damage to his brain.16 However, he’d be out several games and he suffered from headaches for most of the rest of his baseball career.17

When Senerchia was hit, not all teams were enforcing the use of batting helmets. Joe Kelly, writing for the Lubbock Avalanche-Journal, summarized the position favoring helmets.

“Some fans may be inclined to laugh at the plastic helmet caps that the Hubbers are wearing this year, but the players aren’t. They’ve already seen where they were good for them, although that doesn’t mean all of them like the semi-flexible lids.

“Three players were saved by them at Huntsville when they were beaned. It shakes up a player, but it saves a concussion or a more serious injury. It’s mandatory in the Pittsburgh chain this year.

“While Lubbock was training at Huntsville, Sonny Senerchia of Houston was beaned, received a concussion and was, for a while, feared to be dying. The accident could have been averted if he had been wearing a helmet.

“Actually the caps are light, have air holes and there is a foam rubber ring around the inside to keep them on the head. It’s a noticeable change at first, but everyone gets used to them after a while. It’s a wise precaution.”18

Years later, Senerchia would look back and say that the Houston squad was probably the best team on which he had played. Teammates included Ken Boyer, Don Blasingame, Larry Jackson, and Luis Arroyo. Houston won the Texas League championship and later the Dixie Series when the season was over. But for Senerchia, it was the beginning of a change to his baseball career path. He was changing positions.

Senerchia was no longer thought to be a prospect for third base or the outfield, and he was plagued by headaches – yet some smart baseball person noticed that he could help with his strong throwing arm. Starting in 1955, Sonny became a pitcher. He began on the mound at Allentown in the Class A Eastern League, where he went 8-8 with a solid 2.75 earned-run average despite not having a breaking ball or great control. At the end of the season, he was a throw-in when the Cardinals and Redlegs made a trade – Senerchia became the property of Cincinnati. At first, he was assigned to Seattle in the Pacific Coast League, but he wound up pitching for Nashville instead.19

The Reds liked his arm, but not his lack of control. A scouting report from pitching coach Tom Ferrick said his live fastball moved when thrown overhand and sank when thrown side-arm. However, he wasn’t ready for the majors. He couldn’t be depended on to throw strikes.20 In fact, he couldn’t find the plate at all in 1956 – walking 11 in three innings. The harder he tried, the wilder he got. Reds management dispatched Senerchia to Class A Savannah, where he finished the season with a lousy record but a respectable 3.53 ERA.

The following season, the Reds moved Senerchia up to Triple-A Louisville but decided after a few weeks to send him to Monterrey, Mexico. Senerchia wanted nothing to do with a move to Mexico – so now, the Reds didn’t like his control AND his attitude. Cincinnati suspended Senerchia for the remainder of the season.21

Senerchia went back to school – he got his master’s degree in music and prepared to switch careers back to music and teaching. Except he got the itch to pitch one more time. Senerchia explained it this way:

“I’ve had this conflict all my life between music and sports. While playing baseball professionally, I would miss music terribly. Then, in the offseason, I couldn’t wait to get to Florida for spring training.”22

Dick Sisler, who managed the Nashville Vols, gave Senerchia that chance, and the kid who hadn’t touched a baseball in eight or nine months looked solid right away. Knowing about his control problems, Sisler warmed to his effort and attitude.

“There’s always the necessity of getting it over the plate,” Sisler noted, “but Sonny didn’t have bad control out there today. His fastball zooms and he had a good curve, which I hadn’t been told about before.”

“I’ve heard a lot about him having a bad attitude,” Sisler added, “but he hasn’t shown it to me here. In fact, his good attitude has been one of the outstanding things about his work so far. There isn’t the slightest doubt that he could help us if he continues to throw with as much control as he did today.”23

Senerchia didn’t stick. He pitched a season with Sioux City in the Western League and called it a career. He went home and picked up his violin.

When he began playing the violin seriously again, he found at first that it “seemed like a toothpick” in his hands. “I had to put a lot of time into music when I came back,” Senerchia said. “On a lot of jobs, I was competing with men who never left music. There was a tremendous amount of tension and pressure – just like in baseball.”24

He never touched the violin during the baseball season and didn’t get much chance to play it in the offseason either. “I would play it on occasion,” he recalled, “but only to fill a need. It was difficult anyway, because at the end of each season, I’d have calluses at the bottom of each finger and my joints would be very tight – and you have to be loose to play the violin.”25

Fortunately, his hands still worked. Despite many baseball injuries, he never hurt his left hand – the hand he used to “work the technique” while playing violin. As he told the Asbury Park Press, “I broke the middle finger of my right hand once, but that’s the bowing hand, and it doesn’t matter as much. With the left hand, you need every finger.”26

His first jobs weren’t in music – he had much to learn. And teach. So, he taught physical education at the high-school and college levels and coached the school’s baseball teams. While teaching physical education at Livingston High School he met his future wife, an English teacher named Dorothy Siegel. Over time they had three children: Susan, Steve, and Kenneth. He left the high-school world to coach at Monmouth State, teaching and coaching. The rest of his time he spent honing his music skills.27

Senerchia played several recitals, including spots as a featured soloist. In time he was named concertmaster of the Bloomfield Philharmonic Symphony Orchestra and won a scholarship to study violin at the Manhattan School of Music under Raphael Bronstein. In the late 1960s, he returned to the public-school system and developed an orchestra for middle- and high-school students while teaching at Toms River High School.28

Did Senerchia make the right decision while a college student?

“It’s a funny thing,” Senerchia once mused. “I often wonder what would have happened if I’d continued with the violin. I can play in an orchestra now, but I always wonder how far I could have gone as a soloist.”29

As he continued to play and improve, Senerchia played for the Garden State Philharmonic and the State Philharmonic and the State Orchestra of New Jersey, and on a freelance basis with other groups, like the New Jersey Opera Company and the New Jersey Ballet Company. Senerchia also played with some famous entertainers, like Pearl Bailey and Jack Benny. The latter often featured a violin in his comedy routines. “It was an act where Benny stood up and did some solo violin cadenzas,” Senerchia said, “and the concert master and I, in turn, got up and broke in just as he reached a difficult place in the music. Then he told us to get off the stage.

“At the end, Benny called us back and had us take a bow. It was a real comedy act, and it got quite a hand.”30

Life wasn’t all baseball and music. In his later years, Senerchia raced in the Sports Car Club of America (SCCA), and he became a pilot. Okay – there was still baseball and music. He started playing other instruments in jazz groups, including the clarinet, saxophone, flute, and piano. He played softball on a ridiculously competitive team past his 70th birthday.31

On November 1, 2003, Senerchia was riding his motorcycle in Freehold, New Jersey, when he was involved in a nasty accident.32 In an instant, a man who constantly expanded his life and skills and knowledge and shared them with others was gone.

One wonders if Sonny Senerchia sold either his baseball career or his musical career short by not focusing on one thing. Maybe – but he was still able to live well in both worlds. Branch Rickey said it best when he observed that the young third baseman had “the equipment of a ballplayer but the temperament of a musician.”33

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to Rory Costello and Len Levin who reviewed this essay, and to Jeff Findley for providing fact-checking services.

Sources

1930, 1940, 1950 US Censuses (accessed via Ancestry.com)

US Social Security Indices (accessed via Ancestry.com)

Notes

1 By coincidence, Basinski also signed a contract with Branch Rickey, who was then with the Brooklyn Dodgers, for whom Basinski played in 1944 and 1945.

2 His Baseball-Reference.com page says 1931, but Senerchia appears in the 1930 US Census (with sister Carmella, a year older) and his record with the Social Security Administration notes a 1929 birth year. Senerchia’s wife also said in a website exchange that he was born in 1929.

3 “Shaughnessy Slaps Charge on All League, Club Passes,” Ottawa Journal, February 11, 1954: 26; Les Biederman, “The Scoreboard,” Pittsburgh Press, August 28, 1952: 37.

4 “Former Pirate Now Plays to Crowds in Concert Hall,” Asbury Park Press, January 18, 1968: 18.

5 Jim Sullivan, “Then and Now: ‘Sonny’ Senerchia Played for the Pirates in 1952,” Asbury Park Press, April 19, 1964: 48.

6 Ed Reiter, “Beethoven vs. Baseball: Senerchia Torn Between 2 Worlds,” Asbury Park Press, March 5, 1972: 72; “Former Pirate Now Plays to Crowds in Concert Hall.”

7 “First Game of Season Tomorrow,” Millville (New Jersey) Daily Republican, April 23, 1948: 10; “Indians Win 10 Straight Before Losing Last Game,” Zanesville (Ohio) Times Recorder, September 12, 1949: 13.

8 “Beethoven vs. Baseball.”

9 “Beethoven vs. Baseball.”

10 “Shaughnessy Slaps Charge on All League, Club Passes.”

11 “Pirates Bow to Pats, 2-1; Senerchia Goes to Pittsburgh,” Burlington (North Carolina) Daily Times-News, August 19, 1952: Sports 2.

12 Richard Minor, “This Sporting World,” Burlington Daily Times-News, September 3, 1952: 14.

13 “Bucs Split Pair as Necciai Cops First Victory,” Indiana (Pennsylvania) Gazette, August 25, 1952: 11.

14 Biederman, “The Scoreboard.”

15 “Devine Mails 26 Wing Pacts,” Rochester Chronicle, January 29, 1954: 30.

16 “Sonny Senerchia Seriously Injured by Pitched Ball,” Danville (Virginia) Bee, April 7, 1954: 10.

17 “Beethoven vs. Baseball.”

18 Joe Kelly, “Between the Lines,” Lubbock Avalanche-Journal, April 18, 1954: 17.

19 “Cards, Redlegs Swap Lawrence, Collum,” Albuquerque Journal, February 1, 1956: 18; “Senerchia Optioned,” Pittsburgh Press, March 29, 1956: 22.

20 Lou Smith, “Sport Sparks,” Cincinnati Enquirer, March 25, 1956: 54.

21 F.M. Williams, “Vols’ Senerchia Shines in Reclamation Stint,” Nashville Tennessean, March 16, 1958: 30.

22 “Beethoven vs. Baseball.”

23 Williams, “Vols’ Senerchia Shines in Reclamation Stint.”

24 “Beethoven vs. Baseball.”.

25 “Beethoven vs. Baseball.”

26 “Beethoven vs. Baseball.”

27 “Former Pirate Now Plays to Crowds in Concert Hall”; Sullivan, “Then and Now: ‘Sonny’ Senerchia Played for the Pirates in 1952.”

28 “Former Pirate Now Plays to Crowds in Concert Hall”; “Ex-Pirate to Perform in Concert,” Asbury Park Press, January 6, 1970: 18.

29 “Beethoven vs. Baseball.”

30 “Beethoven vs. Baseball.”

31 Obituary: Emanuel Robert Senerchia, Asbury Park Press, November 7, 2003: 19.

32 Obituary: Emanuel Robert Senerchia.

33 “Beethoven vs. Baseball.”

Full Name

Emanuel Robert Senerchia

Born

April 6, 1929 at Newark, NJ (USA)

Died

November 1, 2003 at Freehold, NJ (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.