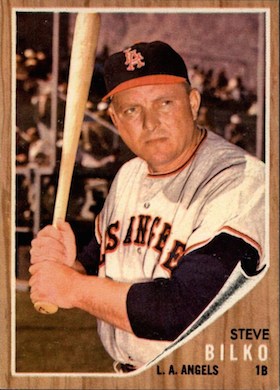

Steve Bilko

Steve Bilko was a heavy hitter.

Steve Bilko was a heavy hitter.

Baseball encyclopedias list him at 6-foot-1 and 230 pounds, the greatest tonnage that baseball allowed in print in the 1950s until the mammoth Frank Howard came along. When anyone asked Bilko how much he weighed, as so many did, he’d say between 200 and 300. Years later he told writer Gaylon White that his best playing weight was 254, but he sometimes topped 270.

Bilko became a minor-league legend in a bandbox ballpark that was built for his right-handed power stroke. For three consecutive seasons “the Babe Ruth of the palm-tree division” was elected the Pacific Coast League’s Most Valuable Player. 1 “He was our Babe Ruth, Mickey Mantle, Ted Williams all rolled into one,” said Bobby Grich, a young Southern California fan who grew up to be a major-league All-Star.2 But Bilko’s big-league career was an unending series of disappointments.

The constant focus on his waistline may have held him back as much as his batting line. Bilko was the Chris Christie of his time, a favorite butt of fat jokes. He wasn’t fat, just big-boned, several teammates said. The sportswriter Red Smith called him “a great lummocking, broad-shouldered, wide-beamed broth of a boy.”3

Stephen Thomas Bilko was a refugee from Pennsylvania coal mines, born in a neighborhood of Nanticoke called Honey Pot on November 13, 1928, the first of two sons of Stephen and Elizabeth Bilko. His father, a contractor who supplied labor for the mines, hired the teenage Steve to feed the mules on Sundays. That meant confronting a herd of large, hungry animals. “Sometimes they would pin me against the sides and scare the hell out of me,” he remembered.4

Stephen Sr., a sandlot ballplayer who was bigger than his son, put a baseball in the boy’s hands almost as soon as he could walk. Northeastern Pennsylvania was better known for football, and Steve was an all-state fullback and guard, but baseball was his love.

Nanticoke native John Grodzicki spotted him first. A top Cardinals pitching prospect, Grodzicki came home in 1945 to recover from a war wound that ruined his career. He tipped scout Benny Borgman to the blond man-child who was crushing a white ball instead of black rock.

The first time Borgman saw him, the scout said, “I was convinced that here was a guy who would hit 65 home runs in a single season.”5 The boy was just 16, had not yet started his junior year in high school, when his father allowed him to sign with St. Louis.

The Cardinals sent him to Allentown, Pennsylvania, 70 miles from home. He singled in his only at-bat of 1945. Moving up through the farm system, he hit 29 home runs at Class-C Winston-Salem, then 20 at Class-B Lynchburg, leading the Piedmont League in homers and batting average, and was promoted all the way to Triple-A Rochester before his 20th birthday. There he broke out in 1949 with 34 homers plus a .310 batting average. It wasn’t just the number of long balls, but how long they were: routinely 400 feet or more, according to newspaper accounts, with a 500-footer in Montreal that was talked about for years.

Bilko made his major-league debut in September 1949, going 5-for-17 in half a dozen games. The next spring he got his first real opportunity because the Cardinals’ regular first baseman, Nippy Jones, had not recovered from back surgery. But Bilko reported to spring training as big as a boxcar—260 pounds. He had married his high school girlfriend, Mary Sunder, in January 1950, and blamed his girth on his mother-in-law’s good cooking. He didn’t want to hurt her feelings by leaving food on his plate.

“That’s when the weight thing started,” he recalled. “No matter where I went they said ‘Get on the scale! Get on the scale!”6 Manager Eddie Dyer’s solution: a rubber suit to sweat off the flab. “They’d make that poor fellow run around and sweat and sweat and sweat,” catcher Joe Garagiola said, “and ask him to play nine innings when he was about dehydrated and could hardly get the bat around. And he was still hitting the ball 400 feet to right-center field.”7 Bilko’s natural swing powered line drives to right- and left-center, the biggest areas of Sportsman’s Park in St. Louis. The Cardinals wanted him to pull the ball toward the shorter left-field wall. After a 10-game trial he headed back to Rochester.

With a new manager, Marty Marion, the Cardinals gave him another shot in 1951. He opened the season as a regular but lasted only 21 games, with a .222 average and his first two major-league homers. “A bust again,” Post-Dispatch writer Bob Broeg commented.8 Mary joined him at Triple-A Columbus with their month-old baby, Steve Jr. Before the family got settled, he was transferred to Rochester.

The next spring, under yet another new manager, Eddie Stanky, the Cardinals’ first-base job belonged to Bilko, if he could keep it. “Put him at first base and play him there steadily, and Steve will do all right,” said farm director Joe Mathes. “I know the pitchers in the National League weren’t sorry about it when Bilko went back to the minors [in 1951].”9

Bilko played the first 20 games of 1952, hitting .264 with six doubles, a triple, and a homer, before he went down with a freak injury. Trotting off the field, he tripped over loose sod and fell on his right arm, breaking the bone above the elbow (the humerus). It was quite a day for the Bilko family; that night their second son, Tommy, was born back home in Pennsylvania.

The injury ended Bilko’s major-league season. When his arm healed he was recycled to Rochester, but Stanky didn’t give up on him. That eye-popping power was irresistible, and the Cardinals needed a strong right-handed bat to balance their left-handed stars, Stan Musial and Enos Slaughter.

Bilko opened the 1953 season batting cleanup between Musial and Slaughter. On his fourth try, he stuck. A 13-game hitting streak in May—a smoking 25-for-51—lifted his average above .300. A few days after the streak ended, he struck out five times in one game.

The strikeouts began to catch up with him. The rap was that he couldn’t hit a curve ball, but pitchers also said they could jam him with fastballs because his bat wasn’t quick enough to turn on an inside pitch. That was dangerous; if they didn’t get the fastball far enough in, it was likely to fly a long way.

Dropped to sixth and seventh in the order, Bilko finished with 21 home runs, 84 RBIs, 70 bases on balls, and a line of .251/.334/.412, decent numbers for his first full season except for the strikeouts: 125, the most in the majors and just nine short of the record. A strikeout was an embarrassment in 1953; only three other batters reached triple figures.

Approaching his 25th birthday, Bilko seemed to have won a major-league job, at least tenuously. Then he became a pawn in “baseball’s great experiment.”

Soon after the baron of Budweiser, August A. Busch Jr., bought the Cardinals in 1953, he asked his executives why the club had had no black players. Busch was a capitalist, not a crusader; black people drank beer, too. He ordered the front office to find some.

The Cardinals signed more than a dozen African Americans and paid $100,000 plus two players for another one, first baseman Tom Alston, who had had a big year in the Pacific Coast League. At spring training in 1954 Stanky said he would platoon Bilko with Alston, a left-handed batter.

Alston started on Opening Day, Bilko the day after. Alston’s first two hits were home runs, but by the end of April he was batting .211, Bilko .143. The Cardinals sold Bilko to the Chicago Cubs for something more than the $10,000 waiver price. Bilko believed that the front office wanted Alston to play without the pressure of his replacement looking over his shoulder.

Alston hit only two more homers in two months and lost his job by midseason. Then he became a tragedy. He began hearing voices and spent a decade in psychiatric hospitals.10

Everywhere Bilko went, he found another first baseman ahead of him or waiting for him to falter. In Chicago it was Dee Fondy, a .300 hitter. While Fondy played, Bilko pinch-hit, batting .239 in 92 at-bats. The next spring the Cubs shipped him to their Pacific Coast League farm club in Los Angeles. He appeared to have run out of chances.

Bilko came to Los Angeles at the perfect time—in his prime at 26—and in the perfect place: Wrigley Field, the home of the Angels. The exquisite little park was the original Wrigley, built by the chewing-gum millionaire in 1925 as a clone of the Chicago venue that was still called Cubs Park.

Most important for Bilko, LA’s Wrigley measured just 345 feet in the right- and left-center power alleys, his happy zone, and the wind usually blew in that direction. A few years later the park would become the natural host of TV’s Home Run Derby. A two-story apartment building across 41st Street beyond the ivy-covered left-field wall had iron bars over the downstairs windows and awnings on those upstairs. Before the protection was installed, Los Angeles Times columnist Ned Cronin wrote, “No one would think of sitting down to dinner without wearing a fielder’s glove.”11

The marriage of the ballpark and his uppercut swing made Stout Steve the Slugging Seraph “a special sort of local legend.”12 Twice in the next three seasons he threatened the PCL record of 60 home runs. He won a Triple Crown and was chosen as the league MVP all three years.

Bilko’s home run derby started in 1955 with 37, a modest number but enough to lead the league. He was second in batting at .328 and in RBIs with 124 to collect his MVP award. With its mild weather, the PCL played a 168-game schedule, and Bilko played every one, but this was the only time he appeared in more than 162.

The PCL was the West’s major league. It had been elevated to an Open classification, higher than Triple A, to encourage the vain hope that it might one day achieve equal status with the American and National. (Think of Lucy holding the football for Charlie Brown.) PCL teams traveled by air rather than bus and paid the biggest salaries in the minors. Bilko signed a 1956 contract for a reported $14,000. Under a rule that applied exclusively to the PCL, he waived his right to be drafted by a big-league club so the Angels could sell him to the highest bidder. It was his strategy to get a fair shot in the majors: “I figured that if a club wanted me bad enough to put a lot of money in me, they’d give me a good chance.”13

Adding to Bilko’s star power, almost all Angels home games were shown on local television. In September 1955 his name went national in a new CBS-TV comedy starring Phil Silvers as Sergeant Ernie Bilko, a con artist in an army uniform. “I could as well have been Corporal Hodges or Private First Class Musial,” Silvers said. “I gave it to the guy who needed it.”14

In 1956 the Angels fielded one of the strongest teams in PCL history, nicknamed the Bilko Athletic Club. The roster was a mix of young Cubs pitching prospects and older position players who had washed out in major league trials. Managed by Bob Scheffing, with future manager Gene Mauch as the second baseman and on-field leader, the Angels compiled a 107-61 record. “I saw some teams in the big leagues that couldn’t play as well,” Mauch said later. “Hell, I managed two of them.” (He was talking about the 1961 Phillies and the expansion 1969 Expos.)15

With no suspense in the pennant race, Bilko’s chase of the PCL home run record riveted the fans’ attention. Tony Lazzeri had hit 60 for Salt Lake City in 1925, when the league played a 200-game schedule. By July 29, when Bilko hit his 45th, an LA newspaper was publishing the “Bilko Homerometer” every day. But he managed only two in the next two weeks, and in September went 12 games without clearing the fences.

Bilko was stuck at 55 when the Angels played a season-ending doubleheader. On “Steve Bilko Day” at Wrigley, the guest of honor apologized to fans for failing to break the record. He mashed one drive that hit the top of the right-field screen, but settled for three singles. He had hit 36 at home, 19 on the road.

He won the league’s Triple Crown with a .360 batting average and 164 RBIs, also leading with 215 hits, 163 runs, 104 walks, 410 total bases, and a .687 slugging percentage. Bilko’s home park was not his only advantage. The Angels played most home games in daylight, when the warm air made the ball fly farther, and Mauch was adept at stealing signs to tell him what pitch was coming.

The Bilko Athletic Club was not a one-man team; the Angels combined for a league-record 202 homers. “We were a family,” left fielder Bob Speake recalled. “There was such a tight camaraderie around Bilko. We became Bilko’s boys.”16

Besides his home run exploits, Bilko cemented his reputation as a champion beer drinker. His Angels teammate Jim Brosnan said he would take his evening supply into the hotel bathroom, stuff towels in the cracks around the door, and turn on a hot shower to steam the alcohol out of his body while he drank it. (Don’t try this at home.) Brosnan added, “Bilko could put away a case of beer after a game and you wouldn’t know he’d had a drink.”17

In 1957, with fewer day games and no Mauch, Bilko challenged the record again. Before the season the Cubs sold the Angels franchise and Wrigley Field to the Brooklyn Dodgers. In addition to opening the way for the Dodgers to move west, the sale broke up the super team. The Cubs, after a last-place finish, promoted their top prospects to the majors along with manager Scheffing and Angels president John Holland. The Dodgers, who had three Triple-A affiliates, packed the Angels roster with minor-league vets such as Tom Lasorda and Sparky Anderson, and the club finished sixth.

Bilko was reported to have signed a $15,000 contract for 1957, the biggest in minor-league history, but he later said the salary was a lot more, and he earned a substantial side income from personal appearances. Scheffing said he was a bigger name in Los Angeles than Marilyn Monroe. 18 (Bilko knew and liked the actor John Wayne, but the glitzy Hollywood scene was not his style.) In addition to his slugging, his easygoing manner made him a fan favorite. The club’s PR man, George Goodale, later ranked Bilko with Nolan Ryan as baseball’s leading nice guys.19

Bilko had 54 home runs in September when the Angels came home to finish their season with 13 games at Wrigley Field. Manager Clay Bryant batted him leadoff to give him more chances at the record. Bilko homered in the first two games of the homestand, then went cold. Wary pitchers were throwing balls eye-high. When he fouled out in the next-to-last game, he pounded his bat on the ground until it broke. He failed to connect in his final 11 games and 48 at-bats.

Along with 56 homers, Bilko led the league with 140 RBIs, 111 runs scored, 353 total bases, 108 walks, and 150 strikeouts. Though his batting average fell to .300, his third consecutive MVP award was a foregone conclusion.

In three years with the Angels, Bilko bashed 148 home runs, two-thirds of them at Wrigley. Except for Los Angeles, he hit more than 30 in a season only once. The Slugging Seraph was a Wrigley Field illusion.

“I’ve liked the Coast League very much,” he told a writer, “but I sure want another crack at the majors. Mainly I want to prove something to those jokers who have been saying for three years that Bilko is strictly a minor league hitter.”20

Angels president Holland had once predicted that he would sell Bilko for $200,000. The club probably got only about one-tenth of that when he was sold to Cincinnati after the 1957 season; there weren’t many bidders for a 29-year-old who was typecast as a platoon player and pinch-hitter. Bilko had to take a pay cut to go back to the big leagues.

The deal gave the Redlegs around 700 pounds of first basemen. Ted Kluszewski and Bilko probably could have balanced on a seesaw, and George Crowe checked in above 220. Cincinnati lightened the load by trading Klu to Pittsburgh.

Manager Birdie Tebbetts said he wouldn’t worry about Bilko’s weight: “If he says he plays best at 250 or 240, that’s the way it is.”21 Bilko and Crowe platooned at first base, but that arrangement lasted just a couple of months before Bilko was sent to the Los Angeles Dodgers on June 15, 1958, in a swap for fading pitching star Don Newcombe.

Some observers saw the hero’s homecoming as a PR move by the Dodgers, who had sunk to last place in their first year in Los Angeles. Jim Murray wrote in Sports Illustrated that it “will be good for the fans although not good for the team.”22 Bilko had reservations, too; he had already seen the Dodgers’ bizarre temporary home, the Los Angeles Coliseum. With a baseball field shoehorned into one corner of a football stadium, the left-field fence was just 251 feet from home plate. “I wouldn’t want the Coliseum as my home field,” he had said when the Redlegs visited. “I’m not a pull hitter.”23 The fence fell away sharply to more than 425 feet in left- and right-center, where Bilko hit his best shots.

The Dodgers had no apparent need for him. Although their veteran first baseman, Gil Hodges, was slumping, rookie Norm Larker was on hand as his heir apparent. Bilko started only one game in the first three weeks. LA fans didn’t care what Hodges had done in faraway Brooklyn; a huge banner appeared in the stadium screaming “We Want Bilko.”

The fans got their way on July 9, Bilko’s first start at home. A frenzied ovation ushered him into the batter’s box in the first inning with two men on, and he delivered goosebumps: a three-run homer.

Bilko hit a game-winning home run four days later, and another homer the day after that. But he struck out 15 times in his first 16 games. Used primarily as a pinch-hitter, he batted .208 for the Dodgers while striking out in one-third of his plate appearances.

Embarrassed by a seventh-place finish, the Dodgers promised a youth movement for 1959. “Bilko doesn’t stand a chance,” sportswriter George Lederer predicted.24 When the club demoted him to Triple-A Spokane in the spring, Bilko exploded, “What does a fellow have to do to get a shot up here?”25 He couldn’t believe no other big-league team wanted him. At first he refused to report, but the Spokane manager, Bobby Bragan, convinced him that he could still be a big drawing card in the Coast League.

After Bilko hit .305 with 26 home runs for Spokane, the Detroit Tigers drafted him for his eighth major-league trial. Red Smith wrote, “Stephen Thomas Bilko has been coming up to play first base for one team or another since the dawn of history.”26 Bilko spent 1960 platooning with young Norm Cash and struggling to keep his batting average above .200.

American League expansion bought him yet another chance at age 32. He was an obvious choice for the new Los Angeles Angels, who would play their first season at Wrigley Field. The Angels also picked up Ted Kluszewski in the expansion draft. Manager Bill Rigney put both heavyweights in the Opening Day lineup, with Bilko on unfamiliar ground in right field. He made a fine running catch, but when Rigney was asked if he’d use that lineup again, he said, “I’ll think about that.”27 Bilko played twice more in right, and settled into a first-base platoon with Kluszewski and Lee Thomas.

Playing in 114 games, Bilko hit 20 home runs, 11 of them in his favorite ballpark. The Angels’ final game of 1961 was the last in Wrigley Field’s history. Bilko pinch-hit with two out in the ninth and cleared the left-field wall one more time.

He stayed with the Angels in 1962 when they moved into their new home, Dodger Stadium (the American League club called it Chavez Ravine). Pinch-hitting and playing first occasionally, Bilko managed to hit only two balls out of the spacious park. He added six homers on the road, batting .287 in 64 games. His season ended early when an infected leg wound put him in a hospital in August.

Although his two years with the Angels were the best of his big-league career, the club dropped him in the fall to their Triple-A farm club, which was moving to Hawaii. Bilko asked to be traded closer to home and landed in his old stomping grounds, Rochester. His final professional season was a disappointment. He shared first base in 1963 with two other minor-league veterans, Luke Easter and Joe Altobelli, hitting .261 with only eight homers in 101 games. Easter was as big a hero in Rochester as Bilko had been in LA. Bilko sometimes heard boos when his name was announced in the starting lineup.

Bilko retired from the game at 34 with 76 major league home runs and 313 in the minors. He went to work as a salesman for Dana Perfume Inc. in Wilkes-Barre, commuting distance from Nanticoke, and later was an inspector in the perfume plant. He built a new home just a block from the house where he grew up. His daughter, Sharon, was a high school cheerleader and sons Steve Jr. and Tom played football at Villanova.

In a 1976 interview, he was looking forward to collecting his baseball pension in two years when he turned 50. He didn’t plan to retire, but thought the extra money would allow Mary to quit working.28

He didn’t get there. Bilko died at 49 of undisclosed causes on March 7, 1978.

Years later, when some members of the Bilko Athletic Club wanted to organize a reunion of the great 1956 team, Gene Mauch asked, “How can we have a reunion without Bilko being there?”29

Additional Source

Bilko, Mrs. Elizabeth, as told to Paul Gardner. “Should Your Son be a Baseball Player?” Parade, June 29, 1952.

Notes

1 Jon Carroll, “Bilko’s Army,” unidentified clipping in Bilko’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame library, Cooperstown, New York.

2 Gaylon H. White, Bilko Athletic Club Blog, April 27, 2014. http://www.bilkoathleticclub.com/blog/bilkomania-topic-of-presentation-at-l-a-sabr-meeting/ accessed December 3, 2016.

3 Red Smith, “Views of Sport,” New York Herald Tribune, March 14, 1950, in HOF file

4 Melvin Durslag, “It’s Much Better Than the Mules,” Los Angeles Examiner, May 24, 1961, in HOF file.

5 Jerry Izenberg, “Bilko never saw the promised land,” New York Post, March 9, 1978: 66.

6 White, The Bilko Athletic Club: The Story of the 1956 Los Angeles Angels (Lanham, Maryland: Rowman and Littlefield, 2014), 85.

7 Joe Garagiola interview by Gaylon H. White.

8 Bob Broeg, “Jones-Fired Cards Beat Dodgers, 6-4,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, May 20, 1951: 1D.

9 “Bilko Able to Handle First Base Berth, Mathes Insists,” The Sporting News, March 5, 1952: 4.

10 Derrick Goold, “Tom Alston: Seven Years After Jackie, 53 Years Ago Today,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 13, 2007. http://www.stltoday.com/sports/baseball/professional/birdland/tom-alston-seven-years-after-jackie-years-ago-today/article_fd7a5d4a-371a-5b49-92f3-bb28414aa398.html, accessed November 16, 2016.

11 Ned Cronin, “Cronin’s Corner,” Los Angeles Times, September 15, 1956: 15.

12 Jon Hall, “So Help Me,” Los Angeles Times, March 10, 1978, III-3.

13 Jack Murphy, “Time Is Running Out for Bilko in Quest for Lazzeri Record,” San Diego Union, August 21, 1956: 17.

14 Red Smith, “Views of Sport,” syndicated column in Seattle Times, March 18, 1958: 28.

15 John Schulian, “Of Stars and Angels,” Sports Illustrated, June 21, 1993. http://www.si.com/vault/1993/06/21/128782/of-stars-and-angels-once-upon-a-time-tinseltown-was-a-heavely-place-to-watch-minor-league-baseball, accessed November 12, 2016.

16 White, The Bilko Athletic Club, 149.

17 Peter Golenbock, Wrigleyville (New York: St. Martin’s, 1996), 333.

18 Smith, “Views of Sport,” syndicated column in Seattle Times, March 18, 1958: 28.

19 White, The Bilko Athletic Club, 79.

20 Hank Hollingsworth, “Sports Merry-Go-Round,” Long Beach (California) Independent, September 18, 1957: 24.

21 Associated Press, “Birdie To Let Bilko Decide Own Weight, Won’t Weaken Him,” Cincinnati Enquirer, March 9, 1958: 78.

22 Jim Murray, “Coining Gold in the Cellar,” Sports Illustrated, June 30, 1958. http://www.si.com/vault/1958/06/30/578849/coining-gold-in-the-cellar, accessed November 12, 2016. Years later Dodgers GM Buzzie Bavasi said the club had acquired Bilko as a PR move to help convince LA voters to approve plans for a new ballpark in Chavez Ravine. Bavasi’s memory was faulty; the ballpark referendum took place on June 3, before Bilko was traded to the Dodgers on June 15.

23 Bob Kelley, “Bob Kelley Says,” Long Beach (California) Independent, June 18, 1958: C3.

24 George Lederer, “Dodgers Bank on Youth Next Year,” Long Beach Independent Press-Telegram, September 28, 1958: C4.

25 L.H. Gregory, “Greg’s Gossip,” Oregonian (Portland), April 14, 1959: 2-1.

26 Smith, “Views of Sport,” syndicated column in Seattle Times, March 17, 1960: 30.

27 Al Wolf, “Wind Shift ‘Robs’ Hunt of Home Run,” Los Angeles Times, April 28, 1961: II-2.

28 White, The Bilko Athletic Club, 90.

29 Ibid., 116.

Full Name

Stephen Thomas Bilko

Born

November 13, 1928 at Nanticoke, PA (USA)

Died

March 7, 1978 at Wilkes-Barre, PA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.