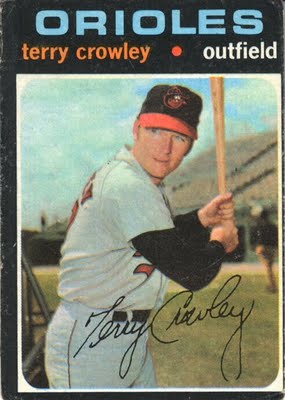

Terry Crowley

“They say I’m a good pinch-hitter, but maybe if I ever came to the plate 500 times, they might learn I’m a good hitter, period.” — Jim Henneman, The Sporting News1

Terrence Michael Crowley was born on February 16, 1947, in Staten Island, New York, and grew up rooting for the Yankees. Despite his admiration for pinch-hitting expert Johnny Blanchard, Crowley was a left-handed pitcher in high school, and drew the attention of professional scouts. Starring at Curtis High in Staten Island, the school that sent Bobby Thomson of “Shot Heard ’Round the World” fame to the major leagues, Crowley got to pitch for the city championship as a junior. But he hurt his arm and couldn’t even throw — much less pitch – when he returned for his senior year. Not surprisingly, the demand for Crowley’s services in pro ball dipped accordingly. “Some teams had made offers and said they would wait until my arm got better,” he said. “But I couldn’t realistically go away to play pro ball when I couldn’t move my left shoulder.”2

Terrence Michael Crowley was born on February 16, 1947, in Staten Island, New York, and grew up rooting for the Yankees. Despite his admiration for pinch-hitting expert Johnny Blanchard, Crowley was a left-handed pitcher in high school, and drew the attention of professional scouts. Starring at Curtis High in Staten Island, the school that sent Bobby Thomson of “Shot Heard ’Round the World” fame to the major leagues, Crowley got to pitch for the city championship as a junior. But he hurt his arm and couldn’t even throw — much less pitch – when he returned for his senior year. Not surprisingly, the demand for Crowley’s services in pro ball dipped accordingly. “Some teams had made offers and said they would wait until my arm got better,” he said. “But I couldn’t realistically go away to play pro ball when I couldn’t move my left shoulder.”2

Instead, Crowley enrolled at the Brooklyn campus of Long Island University, the institution that Hall of Famer Larry Doby once attended on a basketball scholarship. He never went back to the mound, but Crowley got his baseball career back on track with a first-team All-American performance as a sophomore. Now married to the former Janet Boyle with a baby daughter, Carlene, he was drafted by the Baltimore Orioles him in the 11th round of the 1966 June amateur draft, but was in no particular hurry to sign unless the price was right.

The Orioles inked one draftee after another, but Crowley kept refusing to sign. Scout Walter Shannon came to watch him play, and after following Crowley around “for a good two months,”3 finally offered a bonus of $27,500 with only a few weeks remaining in the minor league season. Crowley signed, reported to Miami and batted .255 in 19 Florida State League games with only one extra-base hit in his first taste of professional baseball.

He returned to Miami in 1967 and batted .262 with a league-leading 24 doubles in 135 games. Surprisingly Crowley, a 6-foot, 180-pounder never known for his speed, added 10 triples and 21 steals. However, he managed only three homers and 49 RBIs. “The wind blew in from right field so hard, it was impossible for a lefty to hit a home run,” Crowley remembered. “The whole league was like that.”4

After the season the Orioles put Crowley on their 40-man roster, and after a stint in the Florida Instructional League, they promoted Crowley to the Double-A Elmira Pioneers in 1968. “Crow” hit .271 without a home run in 55 Eastern League games playing for Cal Ripken Sr., but he earned a promotion to Triple-A Rochester after a red-hot June. There, he began to hit with power for the first time as a professional, launching eight home runs to go with a .268 average in 75 games. The Orioles sent him back to the Florida Instructional League after the season, and minor-league director Jim McLaughlin speculated that “Crowley may just come up in September for a look after a season in Triple-A.”5

That’s exactly what happened, but not before Crowley overcame a slow start at Rochester to become a unanimous in-season All-Star selection by International League managers. He batted .282 with 28 home runs and 83 runs batted in, walked 69 times, and led the league with 246 total bases. On September 4, 1969, he fouled out as a pinch-hitter in his major-league debut at Tiger Stadium, but notched three hits in his first start (against the Indians) when the Orioles returned home. He got into seven games that September, hitting .333 (6-for-18), and at just 22 years of age, his future appeared very bright.

Nevertheless, Crowley was a long shot to make the Orioles in 1970. The team’s 109 victories had given it the American League pennant in 1969, and no starting jobs were open in the outfield or at first base. Even two reserve outfielders had spots secured, but Crowley forced his way into the mix by hitting .380 in Grapefruit League play. Utility infielder Bobby Floyd became the odd man out, and Crowley was wearing a Baltimore uniform on Opening Day in Cleveland. He didn’t get into the game, but wound up in the hospital overnight when a foul liner one-hopped its way into the Orioles’ dugout and struck him above the ear. He was fine, though, and started the series finale in right field.

Though Crowley began the season as the Orioles’ 25th man, his contribution to the team’s 108-54 record and second consecutive American League East title was substantial. His first major-league home run was a three-run blast off the Minnesota Twins’ Dave Boswell at Memorial Stadium on May 1 that gave Baltimore a lead it wouldn’t lose. He added game-winning home runs in Detroit and Cleveland before the season was through. He batted .257 in 83 games (34 starts). His totals of five homers and 20 RBIs in 157 at-bats were pretty good, and his .394 on-base percentage was exceptional. Perhaps most telling was Crowley’s .290 average as a pinch-hitter, a difficult role for any player, but particularly for a 23-year-old rookie. “It’s a job usually handled by a veteran,” remarked Crowley. “It’s a big adjustment to go from playing every day to pinch-hitting.”6

He made only one plate appearance in the postseason, but earned a World Series ring as the Orioles romped through the Minnesota Twins and Cincinnati Reds by winning seven times in eight tries. “It was like, hey, this is the way it’s supposed to be,” said Crowley. “We pretty much had an All-Star at every position. We had a fantastic pitching staff. It was a great time.”7

The Orioles hoped Crowley would head to Puerto Rico to sharpen his skills in the winter league, but with daughter Carlene about to turn 7 and sons Terry Jr. and Jimmy still in diapers, Crowley elected to stay home and be daddy. When spring training rolled around for 1971, he pulled a hamstring in a running drill, didn’t hit when he was able to play, and wound up getting sent back to Rochester. “It was an emotional adjustment, no doubt, going from the world champions back to the minors,” he said. “I had to fight not only the opposing pitchers, but my situation as well.”8

Crowley was recalled to Baltimore a few times that season, and managed only a .174 average in 23 at-bats over 18 games. At Rochester, he hit cleanup, played first base, and helped the team to a Junior World Series title by smashing five homers in the playoffs. Still, the season was a disappointing setback, and he did go to the Puerto Rican league that winter trying to turn things around.

Fellow Orioles Don Baylor, Rich Coggins, Dave Leonhard, and Fred Beene were also on the Santurce squad, but Crowley gained his most valuable experience of the winter away from the baseball field. Though physically fine, he’d been placed on the disabled list after a disagreement with manager Ruben Gomez, and found himself sitting around the pool one day when heavyweight boxing contender Joe Roman happened by and the two became friends.

“I had boxed informally as a kid,” Crowley recalled. “We always had the gloves, and my dad and uncles always taught me how to fight because they were into the fight game a little bit. When I actually started to fool around with Joe Roman, it was fun and I could handle myself a little bit. I could move around, and I found that doing it every day for the first time, I got to improve.”9

In addition to sparring, Crowley spent about three weeks following the training regimen of Roman, who in 1973 became the first Puerto Rican to fight for the heavyweight championship. (George Foreman knocked him out in one round.) “Boxers are fantastically dedicated guys,” marveled Crowley the following spring. “They get up at 4 o’clock in the morning and go out and run for an hour or so. Every morning. They never miss. I’ve never seen anyone work so hard in athletics and, boy, does it pay off. I feel in great shape.”10

Crowley wasn’t sure where he fit in the Orioles plans heading into 1972, but one major obstacle had been removed when Baltimore traded Frank Robinson to the Los Angeles Dodgers. Crowley wound up more or less platooning in right field with his good friend and roommate Merv Rettenmund. “Merv Rettenmund was one of funniest, wittiest, sarcastic type guys that you could ever be around,” said Crowley. “He was a great teammate. Guys loved him, and he was a really funny guy.”11

Crowley got into a career high 97 games in ’72 and hammered 11 home runs in 247 at-bats. In June, he shared the cover of The Sporting News with teammates Don Baylor and Bobby Grich, and received praise from Baltimore coach Billy Hunter in the accompanying story. “I am more surprised at what Crowley has accomplished than the other two,” Hunter said. “We always knew that Terry was a natural hitter, but he has impressed me even more by working very hard at other phases of the game.”12 But, a .193 second-half batting average dropped Crowley’s season mark to .231, and the Orioles missed the playoffs for the first time in four years after a September swoon.

Crowley lifted weights with Rettenmund nearly every day that offseason at a Baltimore YMCA, seemingly in preparation for a great opportunity. The American League adopted the designated hitter rule for the 1973 season and Crowley made his first-ever Opening Day start as the first DH in Orioles history. Veteran Tommy Davis, a two-time batting champion, seized the job in May, though, and Crowley wound up hitting just .206 with three home runs in 54 games. Fed up, he let it be known that he’d welcome a trade. The Orioles sold him to the Texas Rangers in December for a reported $100,000.

After another winter in Puerto Rico to get some at-bats, Crowley expressed optimism about joining a new team. “If I could get about 350 or 400 at-bats, I think I could hit between 15 and 20 home runs and help this club a great deal,” he said. “I’ll DH, play first or the outfield, platoon, anything. All I’d like is the opportunity to play in some predictable fashion.”13

Crowley didn’t even make it through spring training with the Rangers, however. Texas placed him on waivers and he ended up with the Cincinnati Reds. There, he was reunited with Rettenmund, whom the Orioles had also traded away because he wasn’t satisfied playing part time. The pair of ex-Orioles earned one more World Series ring when the Reds went all the way in 1975, but mostly endured two miserable years of dwindling playing time and disappointing production with Cincinnati. Crowley hit .240 with one homer in 1974, then .268, again with a single homer the following year, and saw his at-bats drop from 125 in 1974 to 71 in 1975.

Just before the 1976 season opener, Cincinnati sent Crowley and Rettenmund packing in separate deals. The two friends were so glad to be leaving the Reds that, The Sporting News wrote, they went joyriding back and forth over one of the Reds’ spring training fields in Tampa. More than three decades later, Crowley still wasn’t talking. “No comment,” he replied with a laugh. “Let (Rettenmund) tell you that story.”14

Traded to the Atlanta Braves, Crowley was soon reminded that the grass is not always greener. After he went hitless in seven pinch-hit appearances, the Braves tried to option him to Triple-A. He refused, became a free agent, and wound up back at Rochester a few weeks later after re-signing with the Orioles. Baltimore brought him back to the big leagues in late June, and he hit .246, primarily as a pinch-hitter the rest of the way.

Just before the 1977 season got underway, the Orioles, in a surprise move, decided to keep rookie first baseman Eddie Murray, and Crowley was sent back to Rochester again. “Very mad” is how he described his reaction.15 With four children (daughter Karen arrived in August 1976) between 7 months and 13 years of age, being back at Rochester nine years after his first tour there was not a welcome career move. “I think I’m the best hitter in this league, but I have to prove it,” Crowley said.16

“He doesn’t belong in this league,” observed Tidewater Tides skipper Frank Verdi.17 “He was right,” replied Crowley when the quote was relayed to him years later.18

Playing every day for the first time since 1969, Crowley set out to bat .300 with 30 home runs, and accomplished his goal by the first week of August. The Orioles brought him back to the majors a week later, and he remained a big leaguer for the next six years. “Terry has what you call a classic swing,” observed Hall of Famer Frank Robinson. “It’s one you don’t tamper with.”19

From 1977 through 1981, Crowley delivered a .314 average as a pinch-hitter for the Orioles. “People say you can’t carry Crowley for what he does,” said Earl Weaver midway through Baltimore’s pennant-winning 1979 season. “But he’s already got us three games.”20

“I’ve been doing it for so long that people just naturally think I’m older,” Crowley said in 1978. “I’ve been around for a while, and I’ve been in a couple of World Series. A year ago, people thought I was washed up, though I was only 30 years old.”21

American League managers voted Crowley the circuit’s best pinch-hitter in 1979, and he made them look good in Game Three of that season’s American League Championship Series with a hit that would have driven in the pennant-clinching run had the Orioles been able to hold the lead in the bottom of the ninth inning. Baltimore did advance to the fall classic the next day, however, setting the stage for one of the most memorable hits of Crowley’s career.

The Orioles were trailing the Pittsburgh Pirates 6-3 in Game Four of the World Series entering the eighth inning, but pulled within a run when John Lowenstein smacked a two-run double to the right-field corner. After Pirates ace reliever Kent Tekulve issued an intentional walk to set up the double play, Crowley stroked a pinch-hit double to the same location as Lowenstein’s hit to knock in the tying and go-ahead runs. Baltimore took control, three games to one, and Crowley’s hit would be remembered even more fondly if the Orioles hadn’t dropped the final three games of the series.

“Once you get to the World Series, everything is gravy,” Crowley said. “I had some pressure-filled pinch hits that got us to different pennant-winning teams. Not only that year, but other years that were pressure-filled. If you get a hit, we win the game. If you don’t, we drop into second place. But the one thing about the hit off Tekulve, people started to notice, ‘Hey, this guy’s done that before.’ That was the one that probably got me the most notoriety.”22

The Orioles won 100 games in 1980 and, though they missed the playoffs (the Yankees won 103), it was an especially gratifying year for Crowley. He got 233 at-bats, the second highest total of his career, blasted 12 home runs, and drove in 50 runs while batting .288. He was rewarded with a two-year contract extension to keep him employed through 1983.

Crowley was frustrated, however, when he found himself back in his familiar pinch-hitting role, struggling for at-bats again in 1981. ”I’m coming off one of the most productive years on the club,” he said. “What’s wrong with letting me prove I can do it again?”23

“Terry’s got an awful lot of value as a pinch-hitter,” manager Earl Weaver said. “You can’t be too good at your job, and that’s his job. I think the object of everyone to help the club is to do what he does best, and one of the things Crowley does as well as anyone is pinch-hit. It isn’t that I’m disappointed with what he can do as a DH, but he’s excellent as a pinch-hitter.”24

Though Crowley came off the bench to hit two home runs in 1982, including a walk-off grand slam against the Royals, his average as a pinch-hitter dipped to .194 that season. Nevertheless, when the Orioles had to choose between Crowley and his friend Jim Dwyer for the final roster spot coming out of spring training in 1983, a story in a Baltimore newspaper was headlined DWYER SET TO GO. Crowley hit .357 that spring, so it was a surprise when the Orioles decided to release him instead. Baltimore General Manager Hank Peters called it “one of the toughest things I’ve ever had to do in this job”.25

Crowley was about to accept an offer to become the Orioles’ minor-league hitting instructor when the Montreal Expos called in late May. But he got only 44 at-bats all year, batted .182, and decided to call it a career. “I had some phone calls to go play, but my back was hurting pretty good at that time, and I thought it best and wisest to get into my coaching career, to try to become a hitting coach.”26

Crowley spent 1984 as the Orioles’ minor-league hitting instructor, then served on Baltimore’s major-league staff as the hitting coach from 1985 through 1988. In 1986, the Orioles drafted his son Terry Jr., a shortstop, in the eighth round. (Crowley’s younger son, Jimmy, was the Red Sox’s 11th-round pick in 1991) When the Orioles lost 107 games in 1988, all the coaches lost their jobs except the popular Elrod Hendricks. Crowley spent 1989 and 1990 working with Boston Red Sox minor leaguers.

He returned to the majors in 1991, becoming the hitting coach for a Minnesota Twins club that surprised nearly everybody by going from “worst to first” to win the World Series. He remained there through 1998, and explained part of his approach to instructing hitters this way: “If they’re good enough to get here to this level, then they must be doing something right. Unless there’s something I see that absolutely prevents them from having success at this level, I’ll basically leave them alone and try to help them improve their own style, to improve on their own.”27

“You know, it’s like a signature,” he continued. “If you can read it, it’s not too bad, but when it gets to the point that I can’t read it, I’ve got to straighten their swing out a little bit.”28

“If there’s a hitter who’s capable of hitting home runs, hitting with power and driving in runs, that’s what I’ll strive for. I’d hate to see a player just being a singles hitter if he could hit with some power.”29

The way Crowley fought to get at-bats during his playing career helps him communicate to his pupils the importance of making the most of every plate appearance. “Sometimes I go into detail with them to try to make them understand you can develop good habits just as well as you can fall into bad habits. Once you get in the groove and start hitting the ball good, you have to work as hard as you can to stay there, because in the blink of an eye you can fall into a slump or start to struggle.”30

Crowley left Minnesota after eight seasons and returned to Baltimore in 1999 for a second stint as the Orioles hitting coach that lasted a dozen years. He outlasted six managers and was invited back for a 25th season on a major league staff in 2011, but opted for the reduced travel of a newly created hitting evaluator position instead. Crowley was to evaluate Oriole major and minor leaguers, possible trade and free agent targets and potential draftees.

“I think I was lucky. I had a pretty good swing, and I had some ability and I made the best of it. I would like to have played more. That’s the only regret I have. I wish I could’ve played more, but I turned out to be a pretty good pinch-hitter, so I guess everything worked out.”31

Notes

1 Jim Henneman, “Crowley Fattens Up As Orioles Cinch In Pinch,” The Sporting News, August 5, 1978, 13.

2 Terry Crowley, interview with author, May 17, 2008.

3 Crowley, interview.

4 Crowley, interview.

5 Doug Brown, “Orioles Chirp-Chirp Over Fledgling Flyhawk Baylor,” The Sporting News, November 30, 1968.

6 Crowley, interview.

7 Louis Berney, Tales From the Orioles Dugout (Champaign, Illinois: Sports Publishing LLC, 2004), 102.

8 Crowley, interview.

9 Crowley, interview.

10 Phil Jackman, “Crowley In Boxing Form For O’s Job,” The Sporting News, March 11, 1972, 30.

11 Berney, Tales From the Orioles Dugout, 104.

12 Lou Hatter, “Baylor, Grich, Crowley: Orioles Jewels,” The Sporting News, June 24, 1972, 3.

13 “Crowley’s Confident,” The Sporting News, March 30, 1974, 55.

14 Crowley, interview.

15 “Crowley Doesn’t Belong In International League,” The Sporting News, August 13, 1977, 33.

16 “Crowley Doesn’t Belong,” 33.

17 “Crowley Doesn’t Belong,” 33.

18 Crowley, interview.

19 Ken Nigro, “Crowley Gives O’s Punch In A Pinch,” The Sporting News, June 21, 1980, 35.

20 Ken Nigro, “‘Deep Depth’ Cited for Oriole Sky Course,” The Sporting News, July 21, 1979, 12.

21 Jim Henneman, “Crowley Fattens Up As Orioles Cinch In Pinch,” The Sporting News, August 5, 1978, 13.

22 Crowley, interview.

23 Ken Nigro, “Pinch-hitter deluxe Crowley is a Victim of His Own Talent,” The Sporting News, April 4, 1981, 50.

24 Nigro, “Pinch-hitter deluxe Crowley.”

25 Jim Henneman, “Crowley Shocked By Orioles Release,” The Sporting News, April 18, 1983, 24.

26 Crowley, interview.

27 Crowley, interview.

28 Crowley, interview.

29 “Crowley Takes Over As Batting Coach,” The Sporting News, November 26, 1990, 41.

30 Crowley, interview.

31 Crowley, interview.

Full Name

Terrence Michael Crowley

Born

February 16, 1947 at Staten Island, NY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.