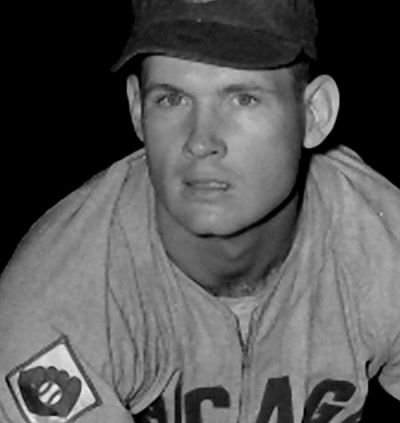

Tom Simpson

Tom Simpson’s career in the major leagues was fairly brief, but he did put in a full season with the Chicago Cubs in 1953 and pitched in 30 games. Simpson was a 6-foot-1 right-hander, listed at 190 pounds. He had five years of minor-league experience behind him when he joined the Cubs.

Tom Simpson’s career in the major leagues was fairly brief, but he did put in a full season with the Chicago Cubs in 1953 and pitched in 30 games. Simpson was a 6-foot-1 right-hander, listed at 190 pounds. He had five years of minor-league experience behind him when he joined the Cubs.

Thomas Lee Simpson was born on September 15, 1927, in Columbus, Ohio, to Charles L. and Olive Simpson. Charles worked as a railroad switchman at the time of the 1930 census; by 1940, he had become a conductor. The couple also had an older son, Charles R., and a younger daughter, Elizabeth.

Tom Simpson was nicknamed “Duke” in his youth. Oddly, it was also his brother’s nickname, so Tom was called “Little Duke.” One of his daughters says, “He was known in the family as that. I don’t think it had anything to do with baseball.”1 The nickname was used in a story about a game he won for Notre Dame, but was otherwise not found in the newspaper coverage of his career.

Tom played sports as a child and graduated from St. Thomas Aquinas High School in Columbus. Aquinas was a college prep type of high school. Of interest, a decade later George Steinbrenner worked there for a year as a basketball and football coach.2Simpson played baseball for the Aquinians in 1944 and also some semipro teams: the Hilltop Merchants in 1944, Model Dairy in 1945, and two teams in 1946: Ace’s Service and Green Cabs.3

He attended Notre Dame and later The Ohio State University. While at Notre Dame, he turned 18 and registered for the draft on September 15, 1945. He pursued his studies and played baseball for Notre Dame. He also enjoyed basketball and football. His eldest daughter, Shelly Jerman, said, “Dad’s most important friendships throughout his life were those he made at Aquinas and Notre Dame.”4His Sporting News contract card shows him in military service beginning on September 21, 1946. Just before entering the service, he completed the American Baseball Bureau questionnaire, writing that his ambition was to become a major-league pitcher. He named his father as the person to whom he owed the most in regards to his baseball career.

Simpson’s professional baseball career began in earnest in 1948, though before entering the Army he was briefly under contract in 1946 to the Minneapolis Millers, a New York Giants Triple-A affiliate.5 The Sporting News reported that he had joined the Millers for the final week of the regular season. It credited his signing to Giants scout Marty Purtell.6

No doubt the Millers had become interested in view of the success he had enjoyed at Notre Dame. He wrote, “First game I pitched at Notre Dame 1-0, twenty innings, knocked in the winning run.”7 A story in The Notre Dame Scholastic, the university’s student newspaper, reported that Jack Barrett had started for the Irish, pitching against “the fliers from Stout Field,” but that Simpson had relieved him after the 14th inning and that indeed he had “hit the winning run across the plate which ended the marathon in a 1-0 Notre Dame victory.”8 An Associated Press story dated the game as July 14 in South Bend and said that Barrett had thrown no-hit ball for the first nine innings, and was replaced after 14 by “Duke Simpson, freshman relief pitcher” who “singled with two out to score Bill Dio Guardi, who had singled.”9

Simpson was stationed at the Brooke Army Medical Center in San Antonio, Texas, at Fort Sam Houston. BAMC still stands today; it tends to service members who have been wounded or injured. “I went back there with him about 12 or 13 years ago,” said Shelley Jerman, “and I noticed there were a lot of severely wounded people there from Afghanistan.” She believes he was at Brooke for the full period of his military service. “He worked as a typist. He told me the reason he worked as a typist was because they didn’t want him to hurt his arm. He was on the base team. I guess they had some big rivalries going on between bases.”10 With the war over, whoever was in charge valued him more as a baseball player than as just another soldier.

It’s notable that the Veterans Administration recognizes Simpson’s service in late 1946 as part of the World War II period. In response to the posed question, “How do I know if I served under an eligible wartime period?” the VA says, “Under current law, we recognize the following wartime periods to decide eligibility for VA pension benefits: World War II (December 7, 1941, to December 31, 1946).”11

On April 9, 1948, Simpson was reinstated in professional baseball.. The next day he was released by Minneapolis but was then signed by the Buffalo Bisons of the International League. His signing was credited to “Claude Dietrich, Buffalo’s chief ivory hunter.”12 A Sporting News article said that both Paul Richards and Dietrich signed Simpson, and that Richards provided him a $3,000 bonus.13 Simpson remained under a Buffalo contract throughout the next three seasons, optioned out each year and then recalled.

On April 23 he joined the Goldsboro, North Carolina, Goldbugs of the Class-D Coastal Plain League. He threw 129 innings in 30 games, with a record of 5-11 and a 4.74 ERA. The team finished in third place with a winning record of 79-61. Player-manager Bill Herring was the top pitcher on the team (19-7, 2.60.) Simpson hit .240 as a batter, 12-for-50 with a pair of doubles and two home runs.

During the season, Simpson met his future wife, Gloria Smith. She worked as scorekeeper at Goldsboro games. “It was all pretty low-key, I think, in those days. She might also have read out some of the commercials,” said Shelley Jerman. “She said something about that once.”14

Gloria and Tom married on February 19, 1949. It was a marriage that lasted nearly 70 years, until Gloria passed away in 2018. They had four children — Shelley, Gloria, Terri, and Thomas. The Simpsons made their home in Columbus at the time. Starting in the winter of 1948, Simpson attended Ohio State in the off seasons, majoring in business. He was also listed as a poultry man at the Southworth Poultry House in the 1951 city directory.

In 1949, Simpson pitched in the Class-B Big State League for the Temple, Texas, Eagles. He won nine games for the last-place (58-89) Eagles but had accumulated more experience at the higher level of play, pitching 208 innings in 40 games, with a 4.67 ERA. The following year, with the Class-A Savannah Indians in the South Atlantic League, he put up the best numbers of his career — 14-9, 3.58. He briefly made the news with a two-hitter on August 2 against Greenville, winning the 10-inning game, 5-3.15 There had also been a game against Charleston when he’d taken a no-hitter into the ninth before giving up two singles.16 The club finished tied for second.

Buffalo brought him up to the Bisons in 1951 and he pitched in Triple A. He started 14 games and relieved in 21 others, building a winning record of 8-6 with a 3.78 earned run average. He allowed only 118 hits in 138 innings and struck out 68. Though his 8-6 record was nothing special, there was a major highlight. On June 22 Simpson pitched the game of his life — a no-hitter against the visiting Toronto Maple Leafs in the seven-inning second game of a doubleheader. He’d recently been promoted from the bullpen and it was just his second start, his first at Offerman Stadium. “I came up with a slider — a good slider — while warming up at Montreal,” he said after the game. “I used it for my ‘out’ pitch that night against the Royals, and it was working perfectly against Toronto. My curve has always been my best pitch, but at times it has behaved queerly. So I realized that to win I’d have to come up with another pitch to use when the curve wasn’t breaking consistently. I didn’t give the slider much thought until early May, and I didn’t begin to work on it until about three weeks ago. It seemed to come naturally, and I have as much confidence in it now as I had in my curve last season.”17 His next game was a 4-2 nine-inning complete-game win against Springfield.

Given the split roles he had had in 1951, Simpson said he really enjoyed working as a reliever. “I suppose most pitchers will think I’ve gone a little soft in the head, but I found last year I was more successful as a relief man than I was as a starter. For some reason or other, I enjoy it more. I get a bang out of coming in to a game during a jam and lifting the ball club out of it.”18

He had that opportunity again in 1952. On November 19, 1951, the Chicago Cubs drafted and signed him. After spending spring training with the big-league club, Simpson was optioned on April 19 to their Triple-A International League club in Springfield. Massachusetts. He worked in 15 games for the Springfield Cubs as a starter and in 12 as a reliever, with an overall 3.68 ERA. He won his first game, 5-3, on May 1, but by year’s end had a discouraging won-lost record of 3-11. That was in part a matter of pitching for a last-place team. He would have worked more but for a sore arm that had dogged him in spring training and later in May. A sore shoulder also put him on the 10-day disabled list in July. On June 16, he pitched three hitless innings against the parent Chicago Cubs during an in-season exhibition game in Springfield.19 The Cubs weren’t prepared to let him go, and in fact promoted him to the big-league roster for the full 1953 season. Simpson left for spring training in Mesa and fared well there, the arm problems of 1952 having subsided. He notably pitched the final three innings of a 10-inning exhibition game against the Chicago White Sox, giving up six hits but getting the win.

It would appear that Simpson made the Cubs staff as the last man. Newspapers gave him just passing mentions that year, and he did not make his major-league debut until May 6 at the Polo Grounds. The Giants had scored six runs in the fourth inning, taking a 7-4 lead. With one out and runners on first and third, Cubs manager Phil Cavarretta called him in to relieve. He induced Davey Williams to ground back to the mound to start a 1-6-3 inning-ending double play. Simpson walked a batter and gave up a single in the bottom of the sixth, but no runs. He was replaced by a pinch-hitter (Cavarretta himself) in the seventh.

He worked in six games in May, not allowing a run in the first four but then being hit for three runs and two runs in the last two games. In June, he pitched in eight more games.

Around mid-June, Ed Prell wrote of the Cubs season, “The only pleasing development was the steady relief pitching of young Tom Simpson.”20 He endured his first defeat on June 14 in the first game of a doubleheader at Brooklyn’s Ebbets Field when Jim Gilliam tripled in two runs in the bottom of the sixth. His earned run average at the end of June was 6.46.

Nonetheless, Cavarretta used him steadily — he appeared in six games in July and seven in August, typically as a mop-up man in games that were out of reach. He had some good outings, but some bad ones as well, which kept his ERA at 6.75 through July and August. He was tagged with his second loss on September 2 in Pittsburgh. He’d been given his first major-league start and it was a disaster. He never recorded an out and the Pirates — who had lost nine games in a row — scored five runs off him in the bottom of the first inning. The biggest blow was an inside-the-park grand slam by a former teammate, Preston Ward. It was the only start of Simpson’s year in the majors.

A week later, the Pirates were at Wrigley Field on September 9. At the end of eight innings, Pittsburgh held a 7-5 lead. Simpson replaced George Metkovich in the top of the ninth. He set down the Pirates in order with two groundouts and a fly ball to center. In the bottom of the ninth, with Roy Face on the mound for Pittsburgh, Eddie Miksis reached on an error by the third baseman. Randy Jackson lined a single to center. Ralph Kiner homered into the left-center field bleachers, a three-run homer that lifted the Cubs to victory, 8-7. Tom Simpson had his first and only big-league win. Simpson appeared in one more game, on September 17 against the visiting Phillies. After seven innings, the Phils led, 11-3. Simpson was again just being asked to do mop-up duty, but he was hit in a way similar to the September 2 game — hammered for five runs without recording an out. It left him with an ERA of 8.40 for the season.

The day after the 1953 season ended, Simpson was contractually released to the Los Angeles Angels, the Triple-A club of the Cubs in the Pacific Coast League. In 1954, he worked exclusively in relief, pitching in 35 games. He was 1-4 with an ERA of 5.17. His arm problems had never fully gone away. As son-in-law Dan Jerman said, “By the time he got to the majors he had this chronic arm trouble and back in those days they couldn’t diagnose things as well. He never had a long career.”21 On September 14, Tom Simpson was released to Macon. He retired from baseball.

Daughter Shelley Jerman detailed some of his life after baseball. He worked in the beer business, in sales for Joseph Schlitz. His work caused the company to have him move to Texas, to different parts of California, and even to Milwaukee for a couple years around 1959-61. The family didn’t really enjoy Milwaukee and he indicated that to Schlitz, which responded by offering him a higher-level position, hoping to incentivize him to stay. Instead, he took a different tack.

“My dad managed to buy a beer distributorship in the San Fernando and San Gabriel Valleys in and around L.A,” said Shelley Jerman. “It was a busy business. That’s all he ever did. He sold the business and retired after that. I think he sold it in the 1970s. He’s been retired for 40 years. He spent the rest of his life pretty much traveling and playing golf. They liked to travel; they were curious cats. They lived in a number of different places.”22

Tom’s wife Gloria died in 2018. As of 2020, Tom had been afflicted with Alzheimer’s for about a decade, and the disease had progressed significantly over the last five years. He is living in a memory care facility and looked after by daughter Terri. Before he had moved to the home, Dan Jerman recalls that Simpson had a “baseball shrine” in his office, with team photographs and the like. Simpson had become friendly with Mike Scioscia and others, and became something of an Angels fan. When he had to be moved to the facility, the family brought a number of the photographs to decorate his new room.

Tom Simpson died peacefully of Alzheimer’s in Folsom, California on the morning of February 7, 2021.

Last revised: February 7, 2021

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Norman Macht and fact-checked by Evan Katz,

Sources

In addition to the Sources cited, in the Notes, the author also relied on Baseball-Reference.com, Retrosheet, org, and a number of research tools provided to members on the SABR.org website.

Notes

1 Author interview with Shelley Jerman, August 30, 2020.

2 There are several stories on the subject. See, for instance, Rob McCurdy, “Greg Swepston recalls when George Steinbrenner was coach, not ‘Boss’,” Marion Star (Marion, Ohio), December 22, 2018. https://www.marionstar.com/story/sports/columnists/2018/12/22/mccurdy-swepston-recalls-when-steinbrenner-coach-not-boss/2314261002/. See also http://www.columbusaquinas.com/History.html.

3 American Baseball Bureau questionnaire completed by Simpson on September 10, 1946, accessed on August 30, 2020 at https://www.ancestrylibrary.com/imageviewer/collections/61599/images/48096_555709_zz-00517?treeid=&personid=&hintid=&queryId=0be36ebdc6671ea724d7f70e1ff94818&usePUB=true&_phsrc=HpP2&_phstart=successSource&usePUBJs=true&pId=57923

4 Shelly Jerman email to author on November 5, 2010.

5 See his Sporting News contract card, available via SABR and the LA84 Foundation.

6 “American Association,” The Sporting News, September 11, 1946: 20. It is noted that Simpson is included in a list of 23 players that legendary scout Tony Lucadello was said to have signed for the Chicago Cubs. See Mark Winegardner, Prophet of the Sandlots (New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 1990), 278. SABR’s Dick Clark credited the signing to Purtell, a resident of Columbus, Ohio. Thanks to Rod Nelson, chair of SABR’s Scouts Research Committee.

7 American Baseball Bureau questionnaire.

8 “Baseball Team Breaks Even During Summer,” The Notre Dame Scholastic, September 28, 1945: 22. Notre Dame’s opponent was a team from the Stout Army Air Field in Indianapolis. Thanks to Joe Smith of Notre Dame Archives. This was apparently college summer baseball; their regular spring season ended on June 16.

9 “Notre Dame Wins in 20th Inning,” Kokomo Tribune, July 16, 1945: 6. A brief note in the Chicago Tribune named the baserunner as Phil Dioguardi. See “Notre Dame’s Nine Wins, 1-0, on 20th Inning,” Chicago Tribune, July 15, 1945: A2.

10 Shelley Jerman interview.

11 https://www.va.gov/pension/eligibility/ . Daughter Shelley Jerman explains, “That was for a VA wartime pension. Social Security uses an even longer period extending into 1947. See https://www.ssa.gov/OP_Home/cfr20/404/404-1302.htm .”

12 “International League,” The Sporting News, May 5, 1948: 20.

13 Cy Kritzer, “Bisons Find No-Hit Sleeper in Bullpen,” The Sporting News, August 1, 1951: 25.

14 Shelley Jerman interview.

15 “Sally League,” The Sporting News, August 16, 1950: 38.

16 Kritzer.

17 Kritzer. He walked four batters, but Kritzer said that each of them was a close call on a 3-2 count. He struck out four.

18 “Simpson Likes Being on Relief,” The Sporting News, March 19, 1952: 28.

19 “Cubs Lose, 4-1, To Farm Club in Springfield,” Chicago Tribune, June 17, 1952: B2.

20 Ed Prell, “Kiner’s Homers Give Cubs Fans Something Pleasing Besides Ivy,” The Sporting News, June 24, 1953: 10. One of Ralph Kiner’s homers would play a significant role for Simpson later in the season.

21 Author interview with Dan Jerman on August 30, 2020.

22 Shelley Jerman interview.

Full Name

Thomas Leo Simpson

Born

September 15, 1927 at Columbus, OH (USA)

Died

February 7, 2021 at Folsom, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.