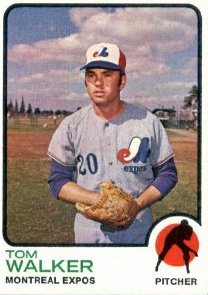

Tom Walker

The hand of fate can be an unpredictable force. In the case of Robert Thomas Walker, the hand wore a baseball glove.

The hand of fate can be an unpredictable force. In the case of Robert Thomas Walker, the hand wore a baseball glove.

Tom Walker’s life has been shaped by the game of baseball. It was a game one summer night that saved his professional baseball career. Then, 16 months later, a conversation with a baseball legend essentially saved his life. He met his future wife, Carolyn, a sister of one of his minor-league teammates, Chip Lang, at spring training in 1974. One of his sons made the major leagues. Baseball and the Walkers are, as the TV sitcom put it, All in the Family.

Robert Thomas Walker was born on November 7, 1948, to Mary and Terry Walker in Tampa, Florida. He discovered at an early age what he called his “God-given” talent at throwing a baseball, and went on to pitch for the Chamberlain High School championship team. The team featured two other future major leaguers, shortstop Mike Eden and third baseman Steve Garvey, who was the best man at his wedding. Walker credited his rivalry with Garvey during high school as his earliest influence. They pushed each other, raising their level of play.[1]

After high school Walker went to Brevard Junior College, where he enjoyed a successful baseball career. The Baltimore Orioles drafted him in the first round (ninth overall pick) in the 1968 amateur draft. Thirty-six years, in 2004, later his son Neil was also drafted in the first round, by the Pittsburgh Pirates. As of 2011 the Walkers were one of five father/son first-round draft choices. The others are the Grieves, Swishers, Burroughses, and Mayberrys.[2]

In 1971 Walker, then pitching for Dallas-Fort Worth of the Texas League, contemplated ending his baseball career and returning to school. The Orioles organization was well-stocked with pitching and he felt he was languishing in Double-A. That was until the fateful evening of August 4. A storm swept through Albuquerque, New Mexico. Presuming the game had been rained out, Walker lay half-clothed on the trainer’s table in the visiting clubhouse. His nap was rudely interrupted by the voice of his roommate, Wayne Garland, who asked if Tom planned on pitching that evening. Walker quickly dressed and rushed onto the field. He had time for only five or six warm-up pitches.[3]

His mound opponent was Albuquerque’s Jim Haller, a former first-round draft choice of the Los Angeles Dodgers. Albuquerque featured two future major leaguers, Lee Lacy and Steve Yeager. That evening the two first-rounders traded goose eggs for 14 innings. Haller scattered nine hits and walked three. His opponent had walked four but given up no hits, and had struck out 11. Haller’s manager, Monty Basgall, removed his pitcher after the 14. Haller protested, especially since the hometown fans seemed to be pulling for his opponent.[4]

Two superb plays preserved Walker’s gem. The first came in the 11 inning when third baseman Steven Green made a barehanded grab on a slow roller by Albuquerque’s Bob Cummings and threw him out. Then in the 14th, outfielder Mike Reinbach made a bizarre grab to rob Cumming of extra bases. Reinbach had knelt to tie a shoelace. When the ball was hit, he quickly recovered and dived backward to snag the ball.[5]

When Walker returned to the dugout after the 14th, his manager Cal Ripken Sr., informed him that he was finished for the night.[6] Ripken did not want to risk injuring his young pitcher’s arm. While Walker was not happy, he respected the manager’s decision. He had great respect for Ripken, considering him the biggest influence in his professional career.

With two outs Albuquerque’s new pitcher, Dave Allen, walked Reinbach, bringing up Enos Cabell. Cabell, who already had three hits, ripped a 3-and-2 pitch for a double, sending in Reinbach with the go-ahead run.

Ripken had a change of heart and sent Walker out to pitch the 15th. Tom retired the Dodgers in order, with Lee Lacy bouncing out to second for the final out.

Walker said in 2011 that he felt that night in Albuquerque opened the eyes of major-league teams. Apparently it worked for the Montreal Expos, who claimed him in the Rule 5 draft after the season.

Walker earned a spot on the Expos squad in spring training and made his major-league debut on April 23, 1972, during a 6-1 loss to St. Louis at Montreal. He came into the game in the ninth inning, the fifth pitcher used by manager Gene Mauch. He started by walking Joe Torre, then got Ted Simmons and Jose Cruz on popups and Lou Brock on a grounder.

After relieving in 13 more games, all Expos’ losses (one of them charged to him), Walker earned his first major-league victory on June 16, over the Atlanta Braves. He relieved Joe Gilbert in the seventh inning with the Expos behind 4-3 and struck out Earl Williams to end the inning. He held the Braves scoreless in the eighth and got the victory when the Expos scored four runs in the top of the ninth. On the flight home, manager Mauch told him, “There’s going to be a lot of these!”[7]

On August 29 Walker got his first save when he preserved a 4-3 lead over Atlanta with two innings of shutout relief. He retired Hank Aaron to end the game. Walker finished his rookie season with a 2-2 record and two saves in 46 games.

Walker and Moore decided to play winter ball in Puerto Rico, along with Expos pitcher Balor Moore and some members of the Pittsburgh Pirates. Roberto Clemente was their manager. Years later Walker felt fate entered his life again. On December 31 Clemente planned to fly in a plane carrying supplies to earthquake victims in Nicaragua. Clemente told Walker and the other players to stay behind and enjoy New Year’s Eve in Puerto Rico.

That night Clemente’s plane burst into flames shortly after take-off and plunged into the dark waters. Walker said he would forever remember that day and how the island was devastated. Clemente’s fellow Puerto Ricans revered him. Out of respect for their fallen hero, the league canceled the balance of the season.[8]

“I can still remember it like yesterday,” Walker said. “We left the airport and it was the last time I ever saw Roberto Clemente. He saved my life by not letting me get on the plane.”[9]

Many baseball experts felt before the 1973 season that pitching was the Expos’ strength. Gene Mauch demonstrated this by using his bullpen aggressively. Mike Marshall appeared in 94 games and Walker in 56. As the number two guy from the bullpen, he rarely saw save opportunities. But he benefited from late-inning rallies by the Expos, and won seven games, with four saves. Statistically it was his best season.[10]

In December 1973 the Expos traded Marshall to the Los Angeles Dodgers. Marshall had been Montreal’s ace and workhorse in the bullpen, and would be tough to replace. Walker volunteered to fill the void. Although he did not have a nasty screwball like Marshall’s, he did own two years’ experience in a major-league bullpen. He returned to the Puerto Rican League to develop a straight change to complement his fastball.[11] But Mauch used him only sporadically, relying instead on Chuck Taylor. On July 9 he was sent down to Triple-A Memphis. At the time his record was a respectable 2-1 with a 2.76 ERA and 40 strikeouts in 49 innings. When sportswriters in Memphis asked why he was there, Walker replied, “I don’t really know why I’m here. They told me to come here, get some work, and sharpen my game.”[12] Mauch cited personal distractions, such as Walker’s ailing mother and his wedding after the season. Walker felt he was in his manager’s doghouse because of a furniture-store commercial he did. Mauch was known to frown on such nonbaseball activities. Walker did as he was told and worked on improving his game. He pitched alongside Chip Lang, his future brother-in-law, in the Memphis Blues’ starting rotation. Before returning to Montreal, Walker started five games and won them all, completing four. He was recalled in early August and Mauch put him in the starting rotation. Over the rest of the season he won one game and lost four.

After the season Walker gave up his apartment in Montreal. He did not foresee himself returning to the team. He was correct; in December Walker and catcher Terry Humphrey were traded to the Detroit Tigers for pitcher Woodie Fryman. The Tigers expected Walker to join with John Hiller and make a formidable left/right combination out of the bullpen.[13]

Detroit’s high expectations for its bullpen evaporated after two consecutive bad relief appearances by Walker, and manager Ralph Houk put him in the starting rotation. On July 7 Walker pitched what he considered to be the best game of his major-league career. Pitching only because the scheduled starter, Ray Bare, was ill, Walker defeated Jim Kaat of the Chicago White Sox, 2-1. Both pitchers threw complete games. Walker scattered eight hits with no walks. Chicago’s only run came on a home run by Ken Henderson. Walker ended the game by striking out a former American League home run leader, Bill Melton. It was such a memorable game that the White Sox manager, the late Chuck Tanner, always mentioned it anytime he saw Walker. In 2010, at a game being televised by the MLB Network, Kaat also mentioned the game.[14]

The Tigers finished with a 57-102 record in 1975, and decided to pursue a youth direction for 1976. At 27 Walker became expendable, and he was optioned to Evansville, then was sold to the St. Louis Cardinals. At the time Walker was 17 days short of qualifying for a major-league pension. He felt that he was a good fit in St. Louis. But he arrived at St. Petersburg for spring training with swollen feet. It was difficult for him to stand, much less pitch. A doctor diagnosed it as gout. When the Cardinals went north, Walker stayed behind in Florida. He began the season with the Triple-A Tulsa Oilers and pitched well, winning an award as the best pitcher on the team. He was selected to the American Association All-Star team and got the save as the All-Stars defeated the Cardinals, 3-1. The All-Stars’ manager, Vern Rapp, said he felt that Walker deserved another chance at the big leagues. Rapp became the manager at St. Louis in 1977, but Walker, hampered by back spasms, was released during spring training. He felt that was the lowest point of his career.

Walker caught on with his old team, the Expos, and, after a stretch with Triple-A Denver (7-0, 1.97 ERA in relief) pitched in 11 games for Montreal, going 1-1. In July he was sold to the Angels, where he appeared in his last major-league game on July 23, giving up two runs in a 10-4 loss to the Minnesota Twins. He was released again. (On his last major-league pitch, Lyman Bostock lined into a triple play.)

Walker wasn’t ready to end his baseball career. The Pirates invited him to spring training in 1978 to compete for a spot in the bullpen. Instead, the Pirates gave the spot to Don Robinson. Walker went to Triple-A Columbus and pitched in six games, then decided to retire. He compared this type of decision with dying.

Walker went into sales after ending his playing career. He credited Charles Bronfman, the owner of the Expos and a major stockholder in Seagram’s Distillery, with pointing him in this direction. He had spent two winters selling whiskey in Detroit and Pittsburgh. Eventually he landed in the health-care industry, and in 2011 was employed by Nemshoff Healthcare Furniture.

The Walkers settled in Gibsonia, Pennsylvania. They had four children, Matthew, Sean, Carrie and Neil, and as of 2011 six grandchildren. Neil, the Walkers’ youngest son, reached the major leagues with the Pirates and was their regular second baseman in 2011. Matthew, the oldest played baseball at George Washington University, was drafted by the Tigers, and was a minor-league outfielder from 2000 to 2004. Sean played baseball at George Mason University. The Walkers’ daughter, Carrie, played basketball at Wagner College and played for Killarney of the Irish Women’s Professional Basketball League. Her husband, Don Kelly, as of 2011 was with the Tigers.

In 1998 Walker helped form a travel baseball team called the Steel City Wildcats, made up of top Western Pennsylvania high-school players. As of 2011, the team had produced 85 collegiate players, including Neil Walker.

A member of the Pirates Alumni Association, Walker took part in the group’s charity events such as golf tournaments, autograph sessions, and speaking engagements.[15]

November 3, 2011

Sources

Newspapers

The Sporting News, April 1972 through December 1976

Mark Smith. “Remarkable Achievement.” Albuquerque Journal, August 4, 2006

Ron Cook. “Walker and His Fmily Living the Dream.” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, June 6, 2010

“Walker, Clemente Share Unusual Bond.” Altoona Mirror, September 2, 2010

Mark Smith. “Walker Still Amazed by His Record No-Hitter in Duke City.” Albuquerque Journal, August 4, 2011

Kevin Gorman. “Walkers First Local Family of Youth Baseball.” Pittsburgh Tribune, August 28, 2011

Magazines

Bob Fulton. “The Marathon Masterpiece.” The National Pastime, 22 (2002), 68-70

Telephone Interviews

Tom Walker, February 22, 2011; August 21, 2011; August 28, 2011

Mark Smith, July 29, 2011

Chip Lang, July 30, 2011

Steve Renko, August 8, 2011

E-mails

Tom Walker, July 3, 2011

Sally O’Leary, August 29, 2011

[1] Conversation with Tom Walker at PNC Park, Pittsburgh, August 21, 2011

[2] E-mail from Tom Ruane, SABR member and co-founder of Retrosheet.org

[3] Bob Fulton, “The Marathon Masterpiece,” The National Pastime, No. 22,, 68-70

[4] Telephone interview with Mark Smith, Albuquerque Journal sports columnist and Albuquerque Dodgers batboy on August 4, 1971

[5] Mark Smith, “Remarkable Achievement, Lost in Time.” Albuquerque Journal, August 4, 2006

[6] Telephone interview with Tom Walker, August 28, 2011

[7] “Walker, His Family Living a Dream,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, June 6, 2010

[8] “Walker, Clemente share unusual bond,” Altoona Mirror, September 3, 2010.

[9] Interview with Tom Walker, February 22, 2011

[10] The Sporting News, April 28, 1973, 34

[11] “Walker Steps to the Front of Expos’ Bullpen,” The Sporting News, March 30, 1974, 32

[12] “Walker Sharpens Game With Blues,” The Sporting News, August 167, 1974

[13] “Tom Walker, Just What Tigers Bullpen Needed,” The Sporting News, May 10, 1975, 11

[14] E-mail from Tom Walker, July 3, 2011

[15] E-mail from Sally O’Leary, August 29, 2011

Full Name

Robert Thomas Walker

Born

November 7, 1948 at Tampa, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.