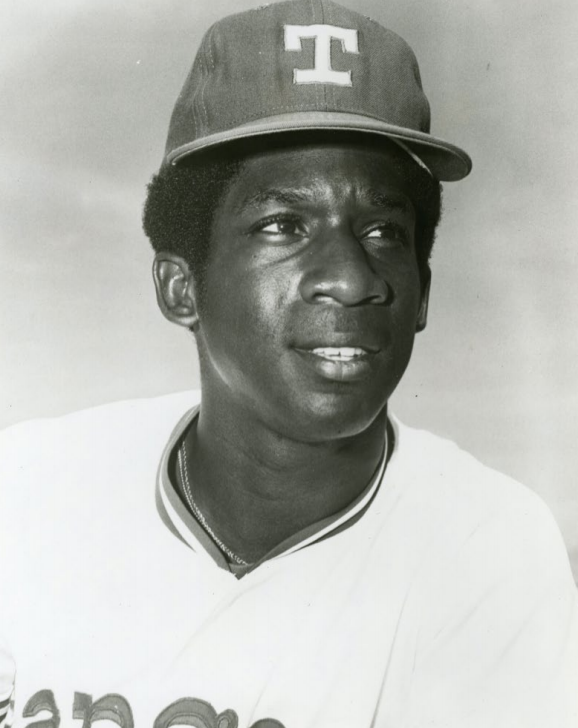

Vic Harris

A utility player is one capable of playing several different positions. Often utility players are not great hitters, yet they are valuable in their ability to fill in for injured regulars, give others in the lineup a much-needed rest, serve as late-inning defensive replacements, and occasionally pinch-hit. In short, they provide teams with a greater level of flexibility. Vic Harris evolved into a prototypical utility player. During a major-league career that spanned eight years, he played in at least 28 games at six different positions.

A utility player is one capable of playing several different positions. Often utility players are not great hitters, yet they are valuable in their ability to fill in for injured regulars, give others in the lineup a much-needed rest, serve as late-inning defensive replacements, and occasionally pinch-hit. In short, they provide teams with a greater level of flexibility. Vic Harris evolved into a prototypical utility player. During a major-league career that spanned eight years, he played in at least 28 games at six different positions.

Victor Lanier Harris was born on March 27, 1950, in Los Angeles, the only child of Fred Martin and Sue Winifred (Adams) Harris. Fred was a compressor operator for the City of Los Angeles and Sue worked as a beautician. The most important life lesson he learned from his parents was to respect and value people. “I was taught to love people,” Harris said.1

Vic grew up as a Los Angeles Dodgers fan and began playing baseball around the age of 7. He began switch hitting at the age of 12. Harris described himself as quiet and attributed his success in baseball to two key ingredients. “I was a natural athlete and I was a team player.”2

A graduate of Los Angeles High School, Harris starred in baseball at Los Angeles Valley College. He was a two-time All-Metropolitan Conference selection and an All-Southern California and Junior All-American.3 The fleet-footed Harris was first drafted by the New York Mets in the 25th round of the 1969 amateur draft. However, he did not sign and elected to return to the school for his sophomore year.

In January 1970 the Oakland Athletics selected Harris in the first round of the 1970 secondary draft. After he signed with the A’s on May 9, scout Phil Pote asked him to return to school and earn his associate’s degree. Harris heeded Pote’s advice and was grateful to him.4 Crediting Pote, Harris said, “He understood I would have a life after baseball.”5 He said he considered accepting a scholarship to play baseball at University of Southern California. Looking back on it, he said, “I wish I had finished my education and gone to SC.”6

Harris was assigned to the Coos Bay-North Bend (Oregon) A’s of the short season Class-A Northwest League for the remainder of the 1970 season. He played in 75 games (67 at second base) and led the team in batting (.326) and stolen bases (30). He struggled defensively and made 19 errors at second base for a .947 fielding percentage.

In 1971 Harris was promoted to the Burlington (Iowa) Bees of the Class-A Midwest League. Joining an infield that included third baseman Phil Garner and shortstop Tommy Sandt, the Bees finished in first place in the circuit’s South Division. Harris led the Bees in games played (120), plate appearances (535), at-bats (444), runs (84), hits (129), doubles (27), walks (77), and stolen bases (39). He finished the year with a .291 batting average, .392 on-base percentage, and .811 OPS.

Harris started the 1972 season with Birmingham of the Double-A Southern League. He played 32 games at second base and was batting .294 with 12 RBIs and 6 stolen bases before being promoted to Iowa of the Triple-A American Association. In 64 games, Harris batted .293 with 6 home runs, 25 RBIs, and 12 stolen bases. Harris said, “I was having a great year. That is, until I reached the major leagues. Then it all came at me.”7

On July 20, 1972, Oakland traded Harris with Marty Martinez and a player to be named later to the Texas Rangers for Ted Kubiak and Don Mincher.8 The trade was first announced on the afternoon of the 19th, yet Martinez played for the A’s that night and got three hits in a 9-6 win over the Milwaukee Brewers. The Brewers filed a protest with the American League, but it was disallowed.9 In the meantime, Harris was en route to Arlington, Texas, where he became the Rangers’ everyday second baseman.

Harris made his major-league debut on July 21 when he came on as a defensive replacement in the top of the seventh inning. Lenny Randle, who started the game at second, replaced Martinez at shortstop, while Harris played second base and occupied Martinez’s spot in the batting order. In the bottom of the eighth, Harris had his first taste of major-league pitching when he was struck out by southpaw Mickey Lolich.

The young second baseman had a dubious start to his major-league career as he endured a 0-for-36 drought before collecting his first major-league hit. As of 2018 this remained a modern record for debut futility.10 He finally collected his first big-league hit when he delivered an RBI single off White Sox right-hander Stan Bahnsen. The hit came in Harris’s 13th major-league game.

Things didn’t get much better for Harris, or the Rangers, during the remainder of the season. In 61 games he hit an anemic .140 and with only 10 RBIs. He made 10 errors and finished with a .960 fielding percentage, significantly below the .977 fielding percentage for all AL second basemen. The Rangers, who had relocated from Washington before the 1972 season, were 16-45 (.262) with Harris in the lineup. At 54-100, they finished in last place in the AL West, 38½ games behind the eventual World Series champion Oakland A’s.

Despite his monumental struggles at the plate in 1972, during spring training in 1973 Harris earned a roster spot as an outfielder and utility infielder. The season proved to be his best in the major leagues. In 152 games he hit .249 with career highs in runs (71), doubles (14), triples (7), home runs (8), RBIs (44), and stolen bases (12). Harris credited the offensive turnaround to manager Whitey Herzog: “Whitey put me out there every day and gave me a chance.”11 However, his defensive woes continued. He made 10 errors in 25 games at third base and another 4 in 18 games at second. Harris attributed many of his errors to throwing difficulties.12

The 1973 season brought with it both memorable and forgettable events in Harris’s major-league career. On May 11, he hit his first major-league home run, off A’s left-hander Vida Blue, a seventh-inning solo shot that cleared the left-field wall at Arlington Stadium. (Harris occasionally reminded Blue of the fact when the two were later teammates with the San Francisco Giants.13

It was also during the 1973 season that Harris fell victim to the hidden-ball trick. The play occurred in a game between the New York Yankees and Rangers at Arlington Stadium on June 6. The Rangers had just trimmed the Yankees’ lead to 3-1 on a Toby Harrah sacrifice fly when the play occurred. According to The Sporting News, “With Texas runners at first and second base, two out and Rico Carty prepared to bat in the fifth inning, New York right-hander Steve Kline circled the mound pretending to rub the baseball. When Vic Harris led off second base, shortstop Gene Michael moved in for the tag and the inning was over. ‘Michael had the ball, but I had to make it look good,’ Kline said.”14 Harris was Michael’s fifth victim of the hidden-ball trick.15 Harris chuckled when remembering the event. “It was the most embarrassing thing I ever did,” Harris recalled with a chuckle. “Although it wasn’t that funny at the time.”16

Later that season, Harris had the less dubious distinction of scoring the winning run in a no-hit, no-run ball game. On July 30, right-hander Jim Bibby no-hit the World Champion Oakland A’s at the Oakland-Alameda County Stadium. Harris was the starting center fielder and batted second. In the first inning, he drew a one-out walk off Blue and came around to score the game’s first run when Jeff Burroughs hit a grand slam. Eight innings later, Bibby retired Gene Tenace on a popfly to second to complete the masterpiece.

During his year-and-a-half tenure with the Rangers, Harris played under three high-profile managers. Ted Williams managed the Rangers in 1972, Herzog managed the Rangers for most of the 1973 season, and Billy Martin for the final 23 games of the season. When asked who his favorite manager was, Harris gave the nod to Herzog while acknowledging that the notoriously difficult Williams and Martin were “good people.”17

During the 1973-74 offseason Harris and Bill Madlock were traded to the Chicago Cubs for future Hall of Fame pitcher Ferguson Jenkins. In acquiring the pair from Texas, the Cubs were hoping they had added an everyday third baseman and second baseman to the lineup. Richard Dozier’s preseason analysis of the Cubs’ revamped infield highlighted the speed the two brought to the club: “Madlock and Harris are the main speed merchants, both with the potential of upwards of 30 stolen bases if given the green light with some regularity.”18

Harris started 30 of the Cubs’ first 33 games at second base, but a season-long slump resulted in diminished playing time as the campaign went on. He was hitting .195 with 11 RBIs and 9 stolen bases when he was injured in a collision at second with the Braves’ Darrell Evans on July 7.19 Season-ending knee surgery followed.

During the 1975 season Harris split time between the Cubs and Wichita of the Triple-A American Association. In 32 games with the Aeros he was primarily used in the outfield and batted .242 with one home run and 11 RBIs. He played in 51 games with the Cubs and was used almost exclusively as a pinch-hitter. In 56 at-bats he hit only .179 with 5 RBIs. On December 22, 1975, the Cubs dealt Harris to the St. Louis Cardinals for light-hitting utility infielder Mick Kelleher.

Harris got off to a great start with the Cardinals in 1976. He was named NL Player of the Week for the week ending May 9 after going 13-for-28 (.464) with 7 RBIs. Entering play on May 15, the second baseman was hitting .315. However, as often was the case throughout his career, he went into another deep slump (.115 over his next 44 games) and increasingly found himself playing a utility or pinch-hitter role. He finished the season with a .228 average with one home run and 19 RBIs. Notably, Harris stole only one base as the knee injury that ended his season prematurely two years earlier had slowed him on the basepaths.

Once again Harris was on the move during the offseason. On October 20, 1976, the Cardinals traded him along with Willie Crawford and left-handed pitcher John Curtis to the San Francisco Giants for right-handed pitchers Mike Caldwell and Jonn D’Acquisto and catcher Dave Rader. The Giants were coming off a 74-88 season and needed to fill a number of holes. Spec Richardson, the Giants’ director of baseball operations, declared that the Giants got the better of the trade. “We got us a spot lefthanded pitcher and two men who can come off the bench and do something, Crawford and Harris. These are people who know what to do all the time,” said Richardson.20

Harris started the 1977 season with Phoenix of the Triple-A Pacific Coast League in a utility role. He played in 24 games in the outfield, 7 at second base and 5 at shortstop. He was hitting .266 with one home run and 18 RBIs when he was called up to San Francisco in late May. Used primarily as a pinch-hitter and utility infielder, Harris finished the season with a .261 average, 2 home runs, and 14 RBIs.

Capable of playing second, short, third, and all three outfield positions, Harris won a position as a pinch-hitter and utilityman coming out of spring training in 1978. However, he started the season in a 0-for-19 funk and never really got going. On July 18, hitting.152 with one home and 11 RBIs, Harris was optioned to Phoenix, where he stayed until major-league rosters expanded in September. After the season he was granted free agency.

On March 6, 1979, Harris signed a minor-league contract with the Milwaukee Brewers. He failed to make the Brewers roster out of spring training and spent the entire season with the Triple-A Vancouver Canadians. Harris was a veteran presence with the team. He played in 142 games and batted .275 with 82 runs scored, 25 doubles, 9 home runs, and 66 RBIs, helping the Canadians capture the Pacific Coast League’s North Division title.

Harris went to spring training with the Brewers again in 1980 with the hope of earning a spot as an extra outfielder. His efforts were stalled when he crashed into a wall and opened a gash behind his right ear that required three stitches and resulted in a concussion and overnight stay in the hospital.21 Harris started the 1980 season at Vancouver and played in 69 games with the Canadians in which he was used defensively in the outfield. He was hitting .273 with 3 home runs, 37 RBIs, and 13 stolen bases when he was called up by the Brewers. After his return to the majors, Harris hit .213 with a homer and 7 RBIs.

Harris’s last game in a major-league uniform was one of his most memorable. On October 5, the last day of the regular season, in a sparsely attended affair against the Oakland A’s, the team that originally drafted him, he closed out his major-league career with a 2-for-6 effort that included the only walk-off hit of his career. The A’s and Brewers were locked in a 4-4 tie in the top of the 15th inning. Against A’s rookie right-hander Dave Beard, Ben Oglivie singled to right with one out and stole second. After Gorman Thomas flied out to left field, the A’s walked John Poff to take their chances with Harris. The Brewers’ right fielder responded with a walk-off single to right, plating Oglivie with the winning run. “It was the only walk-off hit of my career,” Harris said.22

Harris became a free agent after the 1980 season and with no offers from major-league teams, he signed with the Kintetsu Buffalos of the Japanese Pacific League. Joining fellow American Ike Hampton on the Kintetsu roster, the switch-hitting Harris was the Buffalos everyday second baseman. He enjoyed a solid year, batting .268 with a team-leading 22 home runs and 74 RBIs. He also became only the fourth player in Japanese baseball history to hit home runs from both sides of the plate in a game. He accomplished the feat on July 5, 1981, in a game against the Seibu Lions.23

Harris moved from second base to the Buffalos’ outfield for the 1982 season. While he batted .272, his power declined, and Harris totaled only 9 home runs and 35 RBIs. His offensive production declined once again in 1983 (.198-4-23). Despite his struggles at the plate, he became only the second player in the history of Japanese baseball to hit home runs from both sides of the plate in a game twice when he accomplished the feat for the second time on September 1 in a contest against the Nankai Braves.24

Harris looked fondly on his years in Japan, saying, “I really felt comfortable there. I knew I was going to be playing every day.” He also credited the Japanese training regimen for some of his success. “I was in the best shape I was ever in. Over there they get you in condition.”25

With his career in Japan now over, Harris returned to the United States and attempted to reach the majors once more. Now 34 years old, the aging journeyman spent the 1984 season with the Louisville Redbirds of the Triple-A American Association. Harris finished his final season of professional baseball with a .231 average, 5 home runs, and 29 RBIs in 75 games with the Redbirds.

Harris was married twice and has one son. After retiring from baseball, he returned to Los Angeles and worked in the aerospace industry with Rockwell and later Boeing as an emergency fire dispatcher. From 2006 to 2013 he was an instructor for the Major League Baseball Urban Youth Academy in Compton, California.

This biography was published in “1972 Texas Rangers: The Team that Couldn’t Hit” (SABR, 2019), edited by Steve West and Bill Nowlin.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also relied on Baseball-reference.com and Retrosheet.org.

Notes

1 Vic Harris, personal correspondence, January 29, 2018.

2 Ibid.

3 “Hall of Fame: Inductees,” lavc.edu/athletics/Hall-of-Fame/Inductees.aspx.

4 Untitled document, mlblogsmlburbanyouthacademy.files.wordpress.com/2013/02/victor-harris.pdf.

5 Vic Harris, personal correspondence, January 29, 2018.

6 Vic Harris, personal correspondence, February 1, 2018.

7 Ibid.

8 On July 26, 1972, the Athletics sent Steve Lawson to the Rangers to complete the trade.

9 “Marty Martinez,” sabr.org/bioproj/person/e7951fc7.

10 “The Lineup Card: 10 Milestones to Look Forward to in 2013,” baseballprospectus.com/news/article/20040/the-lineup-card-10-milestones-to-look-forward-to-in-2013/.

11 Vic Harris, personal correspondence, January 29, 2018.

12 Vic Harris, personal correspondence, February 1, 2018.

13 Ibid.

14 “Yankees Use Trickery,” The Sporting News, June 23, 1973: 34.

15 Bill Deane, “Gene Michael, Master of the Hidden-Ball Trick,” September 14, 2017, dizzydeane.wordpress.com/2017/09/14/gene-michael-master-of-the-hidden-ball-trick/.

16 Vic Harris, personal correspondence, January 29, 2018.

17 Ibid.

18 Richard Dozier, “Kessinger Cubs’ Infield ‘Stranger,’” The Sporting News, January 26, 1974: 31.

19 “N.L. Flashes: Harris Sheds Cast,” The Sporting News, August 10, 1974: 30.

20 Art Spander, “Spec Sees Giants Profiting on Swap,” The Sporting News, November 6, 1976: 22. Crawford and Rob Sperring were traded to the Houston Astros prior to the start of the 1977 season for second baseman Rob Andrews.

21 Tom Flaherty, “Buck Rodgers: Earth Mission,” The Sporting News, March 29, 1980: 33.

22 Vic Harris, personal correspondence, January 29, 2018.

23 “kaku shu hon rui da ki roku shu (Part I),” 2u.biglobe.ne.jp/~akichan/hr1.htm.

24 “kaku shu hon rui da ki roku shu (Part I).”

25 Vic Harris, personal correspondence, January 29, 2018.

Full Name

Victor Lanier Harris

Born

March 27, 1950 at Los Angeles, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.