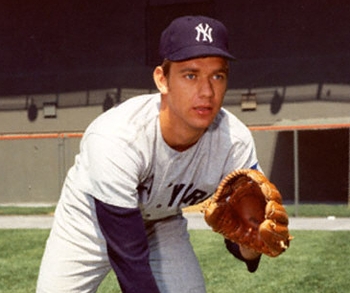

Stan Bahnsen

Over his 16 major league seasons, Stan Bahnsen was a regular rotation starter, a workhorse in a three-man rotation, a closer for a while, and finally an all-purpose reliever and spot starter. Fans at the University of Nebraska named him “The Bahnsen Burner” for his blazing fastball; later in his career he would be “Stanley Struggle,” allowing numerous baserunners, yet possessing the guile to leave them there.1 He pitched in both leagues, sometimes for franchises with fragile identity and ownership. He briefly tested the possibility of free agency, was directly affected by changes in the rules of the game, and played for some of the game’s more controversial owners, managers, and pitching coaches.

Over his 16 major league seasons, Stan Bahnsen was a regular rotation starter, a workhorse in a three-man rotation, a closer for a while, and finally an all-purpose reliever and spot starter. Fans at the University of Nebraska named him “The Bahnsen Burner” for his blazing fastball; later in his career he would be “Stanley Struggle,” allowing numerous baserunners, yet possessing the guile to leave them there.1 He pitched in both leagues, sometimes for franchises with fragile identity and ownership. He briefly tested the possibility of free agency, was directly affected by changes in the rules of the game, and played for some of the game’s more controversial owners, managers, and pitching coaches.

Stanley Raymond Bahnsen was born in Council Bluffs, Iowa, on December 15, 1944, the third of Raymond and Viola Bahnsen‘s four children. Raymond Bahnsen was a brakeman for the Union Pacific Railroad; Viola was a homemaker. None of the family was athletic except for Stan, who wore out the Bahnsen garage door with a baseball. Older brother Jerry recalled Stan’s pitching into a canvas sheet in front of the garage, soon torn to shreds. In an interview with the Des Moines Sunday Register on Bahnsen’s induction into the Iowa Sports Hall of Fame in 2009, Jerry reminisced: “So then we closed the garage doors, and he broke the doors pretty bad. After Stan signed to play professional baseball, one of the first things he did was build my dad a new garage.”

At Abraham Lincoln High School in Council Bluffs, Bahnsen was a star on the baseball team, which usually came up short against cross-town rival Jefferson High. “My high school was more of a basketball school,” Bahnsen recalled. He starred in that sport as well; as a small forward, Bahnsen scored 18 points in the 1963 state title game, but his team lost.

The University of Nebraska recruited the 6’2”, 185-pound right-hander for baseball. In Bahnsen’s only season there he won All-Big Eight and third team All-American honors. When Major League Baseball inaugurated the Rule 4 draft in 1965, the New York Yankees, on the advice of scout Joe McDermott, chose Bahnsen in the fourth round with the 68th pick overall.2 Bahnsen recalled, “I jumped at the opportunity to play major league baseball even though Nebraska had a premier sports program.” He signed with the Yankees and reported to the Columbus (Georgia) Confederate Yankees (Southern League, AA), where he posted a 2-2 record over the remainder of the season.

In 1966, Bahnsen was promoted to the Toledo Mud Hens (International League, AAA) where he was 10-7, threw a no-hitter on July 13, and earned an expanded roster call from the Yankees. On September 9 he made a promising major league debut, pitching two perfect innings in relief against the Boston Red Sox, striking out Joe Foy, Carl Yastrzemski, Tony Conigliaro, and Rico Petrocelli and picking up a save. Six days later, he got his first start, against Washington. Bahnsen showed more promise with a 10-5 complete game win although a rocky three-run ninth took some of the glow off the accomplishment.

A mediocre spring training sent Bahnsen back to the International League for the entire 1967 season, this time with the Syracuse Chiefs. He was under .500 at 9-11 and began to show what was for the times a worrisome tendency—a failure to pitch complete games—though he did muster a seven-inning perfect game against Buffalo on July 9. But the Yankees were desperate for improvement. The team had been losing steadily since their 1964 pennant, when majority ownership in the club was purchased by CBS. At the same time, the cross-town Mets, though not winning a lot of games, drew fans and attention. With Yankee brass hoping their draft choices would start to pay off, Bahnsen made the 1968 club out of spring training.3

Bahnsen got his first 1968 starting assignment on April 17, the Yankees’ sixth game of the season, and did well, pitching into the ninth inning in a 3-2 victory over California. By the end of June, he was firmly ensconced in the starting rotation with a 7-3 record. Bahnsen spoke about his success with The Sporting News and attributed it to better stamina from gaining ten pounds, and “I have better control of my curve, so I throw the fastball less and make fewer pitches. When I depended on my fastball all the time, hitters tended to foul off a lot of pitches.”

Bahnsen ended 1968 at 17-12, with a 2.05 ERA in 267 innings pitched. Four of the losses occurred during weeks when Stan was a part-time Yankee fulfilling Army Reserve duty and pitching only on weekends. The team had improved by 11 games over 1967, and a significant part of this success was attributed to Bahnsen; he was voted American League Rookie of the Year. At the awards banquet, manager Ralph Houk praised his new star‘s discipline in balancing his Army commitment and baseball as early as spring training. Houk told Sporting News writer Jim Ogle, “Stan did it all himself, primarily reporting to camp in the best physical condition he’s ever reported in. He came down for a couple weekends, stayed in shape in the Army and, when he finally joined us on March 17, was ready to pitch.”

For the 1969 season, Major League Baseball enacted two major changes in an attempt to adjust what was perceived as a disproportionate advantage to pitchers—the height of the mound was lowered from 15 to ten inches, and the strike zone was officially tightened. Bahnsen, who at times had difficulty controlling his curve, and whose fastball had benefited from the higher mound, was skeptical. “I don’t like the lower mound, but the smaller strike zone doesn’t bother me since I’m not a spot pitcher,” he told The Sporting News. Bahnsen knew himself well. He struggled with the lower mound throughout 1969, as his record dropped to 9-16 and his ERA almost doubled. A significant factor, given the times, was that Bahnsen tended to tire in later innings. He completed only five of his 33 starts, a performance that magnified the weakness of the New York bullpen.

Bahnsen remained in the Yankees’ rotation in 1970 and 1971, winning 14 games each season. Mel Stottlemyre was the ace of the staff with Bahnsen and Fritz Peterson vying for the second spot. In 1971, Bahnsen showed stamina similar to that of his successful 1968 season as he completed 14 games and pitched 242 innings. Future Hall of Famer Carl Yastrzemski described Stan as “the hardest thrower in the league.” However, the Yankees, who had won 93 games and finished second in 1970, had regressed to 82 wins and fourth place in 1971. Management decided that offense was the problem and saw Bahnsen, with 55 wins at age 27, as a valuable trade commodity.

On December 2, 1971, the Yankees traded Bahnsen to the White Sox for infielder Rich McKinney. The 1971 White Sox had used McKinney as a versatile utility player. He handled a number of different positions with modest fielding skills, but was in the lineup for his bat. At 25, he was expected to be the regular New York third baseman, an upgrade for their weak-hitting infield. Yankee fans disagreed vociferously. Jim Ogle reported a typical fan reaction in The Sporting News: “How could they possibly give up a starting pitcher for another fringe player? I thought they swore not to make a deal unless they obtained a professional infielder,” a Yankee fan wrote. The fans were right.4

In Chicago, Bahnsen took the place of Tommy John, shipped to the Los Angeles Dodgers for heavy-hitting first baseman Dick Allen. The White Sox intended to make Bahnsen more than a typical starting pitcher. White Sox manager Chuck Tanner and executive Roland Hemond were developing the concept of a three-man rotation, with starting pitchers often operating on only two days rest. Bahnsen would join Wilbur Wood and Tom Bradley, who along with Tommy John had started 116 games for the White Sox in 1971.

The concept seemed to work. The 1972 White Sox outperformed projections, remaining in the 1972 pennant race much of the season. On September 12, Bahnsen won his 18th game, combining with Rich Gossage for a six-hit shutout of the Kansas City Royals, placing the White Sox only two games behind the first-place Oakland A’s. The offense had improved with the addition of Dick Allen. He almost won the American League Triple Crown, and did win the MVP award. The “iron-man” rotation started 130 of Chicago’s 154 games with Wood winning 24 games, and Bahnsen a career high 21. Bahnsen took the ball for 41 starts, going the route five times as his WHIP (Walks plus Hits divided by Innings Pitched) rose to 1.332, necessitating extra pitches. The WHIP was above the 1972 AL average of 1.231 and well above the 1.062 Bahnsen posted in his rookie year.

September left the White Sox 5½ games short of the A’s. Encouraged, White Sox management had seen a sharp rise in both wins and attendance brought on by the Allen-led offense and wanted more of it. Over the winter, Hemond executed a trade with San Francisco, sending one of the Sox’s starters, Tom Bradley, to the Giants in exchange for center fielder Ken Henderson and pitcher Steve Stone. The White Sox hoped Stone and Bart Johnson, with help from the deft- touch pitching coach Johnny Sain had shown in implementing the 1972 Tanner-Hemond “iron-man” plan, could make up for Bradley’s 40 starts. Wood and Bahnsen would remain the heart of the rotation.5

The White Sox approached 1973 with great optimism. Announcer Harry Caray typified the attitude in Chicago when he predicted the “Year of the Sock” at the White Sox Hot Stove Press Luncheon. But things did not go as planned. Injuries to Henderson and Allen diminished the offense while Tanner and Sain scrambled to cobble together a rotation beyond Wood and Bahnsen. The two stalwarts held up their side of the pitching load, starting 90 games between them, but both losing a batch in the process. Bahnsen pitched a career-high 282 innings, completing 14 games with an 18-21 won-lost record. Jeff Torborg, a catcher that year with the California Angels, commented on the Sox duo in Phil Pepe’s Talkin’ Baseball: An Oral History of Baseball in the 1970s: “Wilbur could pitch a lot because of that knuckleball, and because of him, the White Sox went with a three-man rotation at times. Bahnsen started throwing overhand, and by the time the season was over, he was throwing sidearm.” Although Bahnsen’s physical woes throughout his career were primarily tied to his back and legs rather than his pitching arm, he didn’t directly disagree with Torborg, telling writer Jerome Holtzman, “It’s twice as hard for me as it is for Wilbur. He throws the knuckler, and of course, that’s not wearing on the arm. I’m essentially a power pitcher. It’s a big difference that should be considered.” Bahnsen had been 18-16 on September 9 before losing his last five games to close at 18-21. “I was going for 20 wins, but instead I wound up with 20 the other way,” he lamented to Holtzman.

The 1973 season ended with the White Sox in fifth place in the AL West Division. Harry Caray’s enthusiasm had turned sour as he blamed players such as Bahnsen and Bill Melton for the team’s disappointing finish.6 When Jerome Holtzman brought up to Chuck Tanner the fact Wood and Bahnsen as teammates had both lost 20 games, something that had not occurred in the American League since 1930, Tanner had praise for his pitchers: “They volunteered to work on short rest. They did it for the good of the team. They should be commended—and don’t forget, they wouldn’t have lost all those games if we hadn’t been crippled by injuries.”7

The 1973 White Sox also had problems off the field. Bahnsen, along with teammates Rick Reichardt and Mike Andrews, had not signed contracts as the season started and were playing under renewal contracts, an option previously untested. If they were not signed by the end of the season, they would become free agents, but Bahnsen finally came to terms on June 19.8

Some of Bahnsen’s successes could be adventures. On June 21, two days after the end of his contract hassle, he pitched a remarkable game—a twelve-hit shutout over the champion Oakland A’s. Impressed with Bahnsen’s tenacity, Chuck Tanner referred to him in a Sporting News interview as a “bulldog” whose shutout was “one of the most courageous performances I’ve ever seen.” From the other dugout, Sporting News writer Edgar Munzel could overhear A’s manager Dick Williams muttering to himself, “A twelve hit shutout! A twelve hit shutout!”

Over the years, Bahnsen’s WHIP continued to rise as he regularly gave up more than a hit an inning. His strikeout rate dropped below five per nine innings. The man once described as “The Bahnsen Burner” was now being called “Stanley Struggle,” a tribute to his tendency to get himself into a jam, then work out of it. But there were notable exceptions to the struggle as Bahnsen occasionally flirted with no-hitters. The closest he came was on August 21, 1973, when, facing the Cleveland Indians, Bahnsen got two outs in the ninth inning before Walt Williams hit a single under third baseman Bill Melton’s glove. Bahnsen came close to pitching a perfect game when he retired the first 23 Minnesota Twins on May 15, 1974, then yielded a solid hit to Bobby Darwin.

Reflecting on the hit by Williams, Bahnsen recalled “I made a good pitch on him. It was a side- arm slider down and away. He got on top of the ball and made it spin under Bill’s glove.” As to Darwin: “He missed first base as he was running. We almost got him there on the relay back to the infield. I’ve always thought how bizarre it would have been if we were able to throw him out and then I get them out in the ninth for a perfect game.”

The 1974 season ended Bahnsen’s status as part of a three-man rotation—the White Sox went with a different arrangement featuring only Wood on short rest in 1975.9 Bahnsen was in the rotation on regular rest until June 15, with the White Sox in last place, Bahnsen was traded with pitcher Skip Pitlock to the Oakland A’s for pitcher Dave Hamilton and outfielder Chet Lemon.

The A’s were seeking their fourth consecutive World Series championship. They had a powerful batting order and two mainstays in the pitching rotation, Vida Blue and Ken Holtzman. Owner Charlie Finley was hoping that Bahnsen would augment the duo. Bahnsen got 16 starts with Oakland and finished 6-7. Boston swept the A’s in the ALCS, but Bahnsen did not see action.

The following season, 1976, was transitional for Bahnsen, now 31. The A’s began using him as a long reliever and spot starter. The A’s were also in transition as a team; Finley went into 1977 dumping salaries, breaking up his perennial champions. When Bahnsen gave up 15 earned runs in his first 22 innings at the start of the season, he was gone by May 22—traded to the NL Montreal Expos for outfielder-first baseman Mike Jorgenson. Bahnsen joined the Expos’ starting rotation, going 8-9 in 22 starts over the rest of 1977.

Bahnsen had benefited both financially and professionally from his stay in Oakland. Charlie Finley had, perhaps uncharacteristically, signed him to a four-year contract. And Oakland A’s pitching coach Wes Stock refined Bahnsen‘s approach. In October 2012 Bahnsen remembered, “Wes convinced me that in Oakland I could get hitters out by throwing a four-seam fastball an inch or two off the plate when ahead in the count, which led to a lot of long fly balls for outs in center field in Oakland.”

The Montreal Expos of the late 1970s were the opposite of Bahnsen’s former team, the A’s. As an expansion team they had never won their division and had to fight for fan attention once hockey season started. But now, with proven winner Dick Williams as manager and a group of talented young position players, things were looking up. Where did Bahnsen fit in? The Expos had not had a solid closer in 1977. The job was open for 1978, the Expos considered Bahnsen a possibility, and he had the job as the team left spring camp.

Bahnsen entered in the ninth on April 8 with a one-run lead over the Mets and a man on base, got the second out of the inning, then yielded a walk-off home run to Ed Kranepool. The Expos continued to use Bahnsen to close for the short-term and he converted his next five save opportunities. But Dick Williams was looking for an alternative, and on May 20 the Expos acquired reliever Mike Garman from the Dodgers. Garman took over as closer; Bahnsen became a middle reliever and earned only two more saves over the rest of the season.

For 1979, Dick Williams had yet another closer, Elias Sosa. Bahnsen, now 34, teamed up with 39-year-old lefthander Woody Fryman to create a formidable set up duo for Sosa.

From 1979 through 1981, Bahnsen provided veteran leadership and quality innings for a young Montreal team that was always in the hunt for the National League pennant. Bahnsen appeared in 137 games over those three seasons, recording 12 wins and ten saves, and making the last three starts of his major league career in 1981. To his young teammates, he was neither the “Burner” nor the “Struggle,” but rather the experienced veteran who had once shared a locker room with Mickey Mantle and Elston Howard. Speaking about pressure on his younger teammates during the 1980 pennant race, Stan remarked to Sporting News writer Ian McDonald “Some of the guys will be answering the telephones when they aren’t ringing.”

Bahnsen encountered some pressure himself on October 4, 1980, when he faced Mike Schmidt with Pete Rose on first base in the eleventh inning of a 4-4 tie, the next-to-last game of the season, with the division pennant on the line. He had always pitched fairly well against Schmidt, allowing only five singles in 20 at bats. But Schmidt homered off a Bahnsen fastball for a 6-4 lead, and ultimately the National League East flag. Alain Usereau described what happened in The Expos in Their Prime—Dick Williams did not want to walk Schmidt and move Rose into scoring position. Catcher Gary Carter had called for a breaking ball, but Bahnsen shook it off, believing it was what Schmidt would expect.

Over the 1980-81 offseason the Expos thought enough of Bahnsen to re-sign him, at age 36, to a three-year, $1 million contract He appeared in 25 games as Montreal finally reached the strike-split postseason, winning the National East Division over the Phillies before losing to the Dodgers in the NLCS. Bahnsen made one relief appearance in the division series, pitching one and a third inning in a 6-5 loss.

The following spring, the Expos released Bahnsen despite the two years remaining on his contract.10 He caught on briefly with the California Angels, and then the Philadelphia Phillies. Philadelphia sent him to Oklahoma City (American Association, AAA), then released him on November 4, 1982. He came back for 25 innings with the Phillies’ Pacific Coast League Portland affiliate in 1983.11

Reflecting on his years in Organized Baseball and the teams he played for, Bahnsen said, “I enjoyed the 1972 White Sox. That group of players was a-laugh-a-minute but on the field they were dead serious. Unfortunately there were no wild cards in those days or in my opinion we could have won it all. And I was on five great Expo teams.”

But Stan Bahnsen still wasn’t done playing baseball. Speaking of his release by the Phillies, he commented, “It wasn’t because I couldn’t pitch, my arm was fine. It was my legs that were shot, I was having all kinds of trouble with them.” Back home in Pompano Beach, he hooked up with the short-lived Florida Senior League, and pitched on weekends for retired Orioles manager Earl Weaver’s Gold Coast Suns during the 1989 season. When that team folded after a year he was 1-2 for the 1990 Daytona Beach Explorers. And then Europe came calling. Bahnsen met a hardware manufacturer from Holland who owned a team located in Haarlem. Bahnsen’s ethnic roots were Danish and Northern German, and he accepted an invitation to be a player/coach at age 48. He pitched in about a dozen games for Haarlem, recalling his fastball still hopping at 85 mph. “Baseball is more laid back there. The teams play two times a week. There’s talent there, but they’re not used to a heavy schedule of games,” he remembered.

Since his retirement from baseball, Bahnsen has had a second career as a promoter in the ocean cruise industry. He has been affiliated with MSC Cruises, developing baseball-oriented programs for the company through which passengers get the opportunity to meet and socialize with former major league ballplayers, including Bahnsen. This entrepreneurial trait is not new to Bahnsen. When he was with the Yankees, he was associated in a promotional firm with other New York professional athletes including Spider Lockhart of the football Giants and Dave DeBusschere of the Knicks. He has also been an instructor at youth baseball camps and did pregame radio for the Yankees’ former Florida State League club in Fort Lauderdale.

As of this writing (2013), Bahnsen has been married to the former Cynthia Wentworth, a comptroller for the Deerfield Wyndham Beach Resort, for over ten years. “She’s a joy to share my life with and enjoys everything I’m involved in. But she‘s a Red Sox fan; I tell people we have a mixed marriage!” He has a son by a previous marriage—Brent, a former high school ballplayer, assists Bahnsen with his promotions and cruises.

Last revised: July 1, 2013

Sources

Robert W. Cohen, The Lean Years of the Yankees, 1965-1975 (Jefferson, NC: McFarland and Company, 2004).

Bill James and Rob Neyer, The Neyer/James Guide to Pitchers (New York: Fireside Books, 2004).

Richard C. Lindberg, Stealing First in a Two-Team Town (Champaign, IL: Sagamore Publishing, 1994).

Richard C. Lindberg, Total White Sox (Chicago: Triumph Books, 2006).

Phil Pepe, Talkin’ Baseball, An Oral History of Baseball in the 1970s (New York: Ballantine Books, 1998).

Alain Usereau, The Expos in Their Prime, The Short-Lived Glory of Montreal’s Team, 1977-1984 (Jefferson, NC: McFarland Publishing, 2013).

Des Moines Sunday Register, August 1, 2009.

The Sporting News, Numerous issues, July 1966, through January 1981.

Baseball-Reference.com

FlyingSock.com

Retrosheet.org

Alain Usereau’s recorded interview with Stan Bahnsen at the June 2012 Montreal Expos’ reunion; Acknowledgment: Alain Usereau.

Author’s telephone interview and e-mail correspondence with Stan Bahnsen, October 2012, March 2013.

Notes

1 Richard Dozer, a Chicago Tribune beat writer, bestowed the name “Stanley Struggle” in the June 21, 1975, Sporting News.

2 The Rule 4 draft began in 1965 to apportion amateur player prospects among major league teams in a more equitable fashion than the prior, unregulated signing system.

3 In The Lean Years of the Yankees, Robert Cohen discusses the club’s need for rotation starters due to the loss of Whitey Ford (to retirement), Jim Bouton (to ineffectiveness), and Al Downing (to a sore shoulder), and a subsequent hope for Bahnsen’s success. 67-68.

4 McKinney hit .215 in 121 at bats for the 1972 Yankees. He committed four errors in a loss to Boston on April 22, was benched after 30 games, and was traded to Oakland after the season.

5 In October 2012, Bahnsen reflected on how Sain had contributed to his skill as a pitcher: “ Johnny Sain improved my curve ball and that took three months to put into game situations, but I feel that his teaching and that improvement kept me in the major leagues as a quality middle reliever and spot starter later in my career.”

6 Bahnsen said in March 2013, “I never had any trouble with Harry Caray, but he crucified Bill Melton.”

7 Bahnsen disagrees in his perception of the circumstances: “I never wanted to pitch with two days rest and never volunteered to do so. Wilbur refused to pitch with three days rest.”

8 Rich Reichardt left the team on June 26 and was released two days later. Andrews was released on July 16. Reichardt caught on briefly with Kansas City, Andrews with Oakland.

9 The 1974 White Sox rotation had been Wood, Jim Kaat, Bahnsen, and Bart Johnson, although Johnson started only 18 games.

10 In The Expos in Their Prime, Alain Usereau refers to a change in the Expos’ strategy, a preference to be competitive rather than seek championships. As a result, several veteran players, including Bahnsen, were released to create a younger roster. 181.

11 Over 16 major league seasons Bahnsen won 146 games and lost 149. He pitched 2,529 innings with a 3.60 ERA.

Full Name

Stanley Raymond Bahnsen

Born

December 15, 1944 at Council Bluffs, IA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.