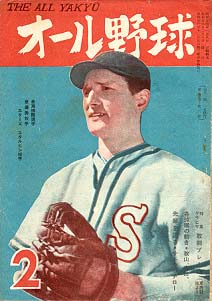

Victor Starffin

Victor Starffin’s life reads like a Hollywood novel and, in a way, so do his pitching statistics …” — Richard Puff

It is highly probable that no professional baseball player — from any era, country or league — ever lived a more erratic, dramatic, and in the end tragic life than did the pitcher today known to the game’s history connoisseurs as Victor Starffin. He is the sport’s only hall-of-fame legend born in the unlikely baseball breeding grounds of the Russian Urals; he wove his diamond legacy in the unlikely setting of pre-World War II Japan; his family history would in the end contain enough political and criminal intrigue to spice the pages of a classic novel penned by Dostoevsky or Tolstoy; his own personal character flaws and his adopted country’s remarkable xenophobia conspired to produce one of the most rapid and dramatic tumbles from grace suffered by any renowned star athlete. Author Richard Puff was hardly guilty of exaggeration when he suggested that the Russian-born immigrant turned Japanese pitching hero lived a life fit for a Hollywood script and also amassed mound statistics appropriate for enshrinement in Cooperstown.1

It is highly probable that no professional baseball player — from any era, country or league — ever lived a more erratic, dramatic, and in the end tragic life than did the pitcher today known to the game’s history connoisseurs as Victor Starffin. He is the sport’s only hall-of-fame legend born in the unlikely baseball breeding grounds of the Russian Urals; he wove his diamond legacy in the unlikely setting of pre-World War II Japan; his family history would in the end contain enough political and criminal intrigue to spice the pages of a classic novel penned by Dostoevsky or Tolstoy; his own personal character flaws and his adopted country’s remarkable xenophobia conspired to produce one of the most rapid and dramatic tumbles from grace suffered by any renowned star athlete. Author Richard Puff was hardly guilty of exaggeration when he suggested that the Russian-born immigrant turned Japanese pitching hero lived a life fit for a Hollywood script and also amassed mound statistics appropriate for enshrinement in Cooperstown.1

Starffin would play a pivotal role in early Japanese experiments with professional baseball and it was only one of the many ironies attached to his unlikely career that Japan’s first great diamond star would not be a native-born son but rather a fortuitous foreign import. Japanese professional baseball history from its earliest years in the 1930s through the dawn of the 21st century has been vividly colored by deep-seated racism, and that fact alone makes Victor Starffin’s rise to prominence all that much more remarkable. Many of Japan’s greatest ballplayers have in fact been drawn from immigrant Korean and Chinese (especially Taiwanese) stock, yet none of the best imports have ever played on an equal footing with more celebrated natives. The island nation’s most recognizable slugging hero, Sadaharu Oh — perhaps the single Japanese diamond star best known to North American fans — found his own career marred from beginning to end by the subtle and all-pervasive Nippon brand of xenophobic prejudice. 2

Despite its prewar successes, the Japanese professional game only surged to real prominence in the aftermath of the Second World War when retired or fading North American big leaguers began to be recruited by the Land of the Rising Sun in a concerted nationalistic effort to elevate the still-inferior local game to coveted major-league standards. But the Japanese have always been zealously proud of their untainted national heritage — a fact only enhanced by the wartime defeats of the 1940s — and “foreigners,” or Gaijin, have never found the going easy in Japan. The same cold-shouldered treatment plaguing early American imports like Don Newcombe, Daryl Spencer, Don Blasingame, and Hawaiian-born Wally Yonamine had already had a telling effect on the career of immigrant star pitcher Victor Starffin more than a decade and a half earlier.

Historian and recognized Japanese baseball authority Robert Whiting has written extensively about the often largely negative Gaijin experience and its roots in the insipient racism at the core of the Japanese national pastime.3 This was a sullied tradition that went back to the earliest years of Japanese professional baseball, the first noteworthy instance occurring in the league’s second full season of 1938 when the spring-session MVP trophy was handed to unheralded Tokyo Senators infielder Hisanori Karita. Hisanori had posted rather modest offensive numbers while playing for the circuit’s worst club, yet he was nonetheless selected for the postseason honor over the league’s top two white stars — Starffin (who led in pitching wins) and American recruit Harris McGaillard (the home-run champ and one of the league’s best hitters). It was only a sign of things to come since runaway Japanese nationalism would surge during the coming war years and then became perhaps even more intense in the aftermath of World War II military defeats (in the mid-’40s) and also during a decade of embarrassing American government occupation (throughout the late ’40s and early ’50s).

Often Japanese-born stars hailing from immigrant families have had to hide their true family backgrounds, sometimes going to great lengths to conceal family roots as the offspring of Korean- or Chinese-born mothers or fathers. The most notable case is that of Japan’s greatest diamond legend, Sadaharu Oh (son of a native Taiwanese shopkeeper) who as a teenager had already been banned from accompanying his high-school club to a wildly popular annual national schoolboy tournament.4 Once fully established in the professional ranks with the Yomiuri Giants as the Central League’s greatest slugging star of the 1960s and 1970s, Oh was cheered across the nation for remarkable batting feats that led not only to rewriting the Japanese record books but also to numerous Yomiuri pennant victories; yet at the same time Oh was never the recipient of the same level of hero worship as that bestowed upon his more popular native-born teammate and heavy-hitting third baseman, Shireo Nagashima.

The most long-suffering Gaijin ballplayers of course were the imported Americans, many of whom were themselves largely to blame for a public unpopularity brought on by their shoddy performances, inability to match unrealistic expectations (automatically attached to them as one-time big leaguers), or stark refusals to adopt to the differing ways of Japanese baseball. Flaky if charismatic ex-Yankee first baseman Joe Pepitone was perhaps the classic case of “the ugly American” phenomenon; recruited at the start of the 1973 season by the Yakult Swallows (for the then-lofty sum of $150,000) Pepitone was a giant bust, displaying arrogance by refusing to accept Japanese standards off the field and providing little return for the club’s investment during the mere 14 games in which he actually appeared (one homer and a .163 batting mark).

Other Americans adjusted admirably and performed heroically in the Nippon leagues — especially another former Yankee, Clete Boyer, as well as slugging San Francisco Giants infielder Daryl Spencer. Nonetheless, there were also obvious instances of outright and unmerited prejudices against foreigners — especially the Americans. Several imported stars were clear victims of schemes to rob them of batting titles, home-run titles, or pitching honors.5 Even Hawaiian-born Wally Yonamine was a prototypical victim of such cultural conflict early in his Tokyo Giants career. A former professional football player (San Francisco 49ers) of Japanese heritage, Yonamine was recommended to the Yomiuri ballclub (by Lefty O’Doul) in 1951 and made an immediate splash in the Central League with his hustling and aggressive big-league playing style (which included hard sliding on the basepaths). But Yonamine’s personal aggressiveness seemed out of tune with the more polite and restrained brand of Japanese play. (Japanese fans were appalled at the seeming illogic of his dashes to first base on sacrifice bunts; the reigning Japanese style was to lay down a bunt and walk immediately to the dugout.) At first a lightning rod for widespread outrage among Japanese fans, Yonamine nonetheless worked hard to adapt and finally won widespread general acceptance mainly on the strength of his three batting titles and a career-capping league MVP award.

During the pioneering prewar years of Japanese baseball, Victor Starffin largely escaped such obvious outward displays of racist attitudes that were soon enough coloring the Japanese version of the professional game. Eventually the imposed status of Gaijin outsider would inevitably catch up with even Japanese-raised Starffin once full-scale Pacific Theater hostilities broke out with the Chinese and Americans and “anti-foreigner” mania was ramped up to a near fever pitch during the expected wartime tidal wave of patriotic nationalism. In the early phases of his career, Starffin’s status as an ethnic “outsider” seemed to take a back seat to his unrivaled achievements as one of the game’s most popular pioneering heroes. His blond hair, blue eyes, and towering frame seemed more charming and engaging than frightening or culturally insulting, and his bulky size and resulting overpowering fastballs were seen primarily as exotic assets for a Tokyo Giants team that already claimed the nation’s widest fandom.

When a homegrown Japanese professional league was initially launched in mid-1930s, Victor Starffin emerged alongside another early Japanese pitching legend, Eiji Sawamura, as one of the twin aces of the immensely popular and successful Tokyo Kyojin (eventually known as the Yomiuri Giants). Founded by a wealthy newspaper magnate in 1936, the Kyojin would quickly emerge as the island’s version of the New York Yankees, a status they still enjoy eight decades later. Sawamura tossed the league’s first two no-hit games, in 1936 and 1937, and Starffin authored the third, also in 1937. While Sawamura’s meteoric fame was tragically short (since he became a wartime casualty before his 28th birthday), the powerful, right-handed Starffin would survive on the Japanese pro circuit well into the modern two-league era, not retiring until 1955, by which time he amassed more records (many still standing) than any other celebrated hurler in league annals. He was the first Japanese leaguer to claim 300 wins and as of 2013 still stood among only a half-dozen to cross that esteemed plateau.6 He still owned the most consecutive seasons (three) with 30-plus victories, most wins in a season (42 in 1939), most career shutouts (83, one better than Masaichi Kaneda), and a career 2.09 ERA. During his spectacular first half-dozen campaigns, he amassed 182 wins (better than 30 per year) against a mere 53 defeats and never allowed his ERA to soar above his 1937 mark of 1.70. And he might have been much better still had it not been for the latent personal demons that would eventually turn his later life into a sustained tale of self-inflicted woe. In the end a long-developing alcohol-abuse problem, likely worsened by public harassment received as a foreigner during World War II, surfaced periodically throughout his final years, causing the breakup of his marriage and even his eventual death in a car wreck less than two years after his premature baseball retirement.

The future Japanese hall of famer was born as Viktor Konstantinovich Starukhin on May 4, 1916, in the midsized village of Nizhny Tagil, a rural outpost tucked in the middle of the Russian Ural Mountain region about 1,000 miles east of Moscow. The youngster’s life was destined to be infused with mystery from its opening hours since there are actually three different versions of his accurate birthdate. Technically the child first saw the light on April 21 (according to the Julian calendar then in use in Czarist Russia); the date would later be modified to May 4 when the post-Revolution Bolshevik government adopted a Western European Gregorian calendar.7 But even if these calendar discrepancies are ignored, there is still a problem with the “official” date since the family had apparently decided that May 1 might be somehow easier to remember. Victor’s mother, Evdokia, had already given birth three previous times, but all the earlier male siblings had fallen victim to fatal illness in early infancy. The fourth and only surviving son was fondly dubbed Weejer by his doting parents and as the only healthy offspring the boy rapidly grew into a strapping and oversized youngster.

Political intrigue and surrounding historical circumstance plagued the small Starffin family from the outset and dogged Victor from his infancy right down to the months and weeks immediately preceding his untimely death. Victor’s dashing father, Konstantine Fedrovich Starukhin, had been born into the pre-World War I (and thus pre-Revolution) Russian aristocracy. In his own youth Konstantine attended a prestigious military academy and upon graduation he rose quickly in the ranks of the czar’s army; with the outbreak of the first truly global warfare that was already raging across Europe by the time of Victor’s birth, Konstantine had apparently avoided being sent to the battle front largely due to his family’s upper-class status and their long record of noble czarist service. But soon enough the crush of world events nonetheless struck a severe blow on Starukhin family fortunes. The first phases of the anti-czarist revolution, in February 1917, forced Konstantine to abandon his army post and join forces with the White Russian rebels — the remnants of the old aristocracy opposing the temporary Kerensky provisional government that had almost overnight ended both the reign of Czar Nicholas II and also more than 300 years of Romanov family rule.

The immediate and multiple dangers facing all members of the old-guard czarist supporters were severe enough to convince Konstantine that it was necessary to dispatch his wife and young son to safe harbor with friends in distant Siberia, the nation’s Far Eastern outpost, where early phases of the Revolution so far had made little impact. What followed was a lengthy and arduous flight romanticized (and perhaps largely fictionalized) by biographer John Berry into a remarkable ordeal involving near-starvation, torturous exhaustion, narrow escapes from disastrous discovery and thus certain execution, and several months of painful trekking on foot and in horse-drawn cart by the heroic mother Evdokia and her brave and resilient infant son Victor.8

If biographer John Berry’s account of the Starffin family’s escape embellishes lost details, it nonetheless certainly captures the essential elements in a remarkable tale of tenacious human survival. After numerous close and even rather miraculous escapes from the Bolshevik military forces and a several-thousand-mile trek to the western edge of Siberia, Konstantine was eventually reunited with his wife and infant son in the village of Krasnoyarsk, from which they made their way farther eastward to temporary refuge in Irkutsk, arriving at the next sanctuary only a few steps ahead of the advancing Red Army. A final equally arduous flight ultimately took the escapees to a Russian refugee community in the sprawling Manchurian city of Harbin, in northeastern China. After a fitful residence in Harbin that stretched to nearly five years, Konstantine finally received the necessary permits and paperwork that would allow his small family to resettle into a new and hopefully improved life in neighboring Japan. The fee for immigration status exacted by the Japanese authorities was 4,500 yen, a hefty price tag that the Starffins were barely able to meet. They did so by selling off some remaining family jewelry that Evdokia had managed to smuggle out of their homeland, having sewn the valued family treasures into the lining of her ragged peasant undergarments before she fled her original homestead.

Eventually settled in the city of Asahikawa on the northern Japanese island of Hokkaido, the long-suffering family finally took up a promising new life in a strange and exotic adopted homeland. A chance meeting with a fellow Japanese refugee on the resettlement train ride to Hokkaido had provided Konstantine with a small startup business as a vendor of imported European fabrics. Evdokia supplemented the family income by baking bread for a local teahouse. Victor also prospered when sent off to an elementary school where his large size and considerable strength made him a natural at the increasingly popular schoolboy sport of baseball. By the time the child reached his early teens he stretched to above 6 feet and towered over his diminutive Japanese schoolmates. His baseball skills were soon so advanced that he was already carving out a substantial reputation as a gifted pitcher not only in schoolboy games but also while performing on weekends for some of Hokkaido’s best all-star amateur nines.

Resurging family fortunes seemed about to take a further prosperous upturn when it appeared that Victor’s budding athletic talent would mean a baseball scholarship at the prestigious Koyo high school in nearby Kobe; so desperately did the baseball powerhouse program at Koyo desire the talents of the young Russian teen that they offered to resettle the entire family in Kobe and provide the parents with a startup bakery business. But the whole plan collapsed suddenly when the region’s other high-school principals formally protested and the offer had to be withdrawn. Victor would have to settle for playing baseball with the local Asahikawa high-school team, which he soon led to several near misses at reaching the prestigious year-end national high-school tournament staged annually in Koshien.

But there would soon enough be yet another family tragedy on the horizon and one far more crushing then the mere scuttling of Victor’s dreams of playing for powerful Koyo high school or leading his team to the Koshien tournament. On the brief visit to Kobe the Starffins had met a pretty Russian immigrant girl named Maria who returned to Asahikawa with them and began working in the Russian-style teahouse they now operated. Konstantine soon became involved in a romantic tryst with young Maria and the stormy affair apparently involved violent arguments between the two over the issues of Russian politics. In February 1933 Konstantine flew into a jealous rage at the girl’s apartment (he apparently suspected her of taking another lover) and brutally stabbed her to death. At first Konstantine admitted the murder was the result of a fit of “sexual jealousy,” but later he changed his story and claimed that he committed the act because he had discovered that Maria was a secret Soviet spy (a strong indication of the mental imbalance that would plague both father and son during their middle-age years). The end result of the inexplicable and horrific crime was a sentence of eight years in a prison labor camp.

But there would soon enough be yet another family tragedy on the horizon and one far more crushing then the mere scuttling of Victor’s dreams of playing for powerful Koyo high school or leading his team to the Koshien tournament. On the brief visit to Kobe the Starffins had met a pretty Russian immigrant girl named Maria who returned to Asahikawa with them and began working in the Russian-style teahouse they now operated. Konstantine soon became involved in a romantic tryst with young Maria and the stormy affair apparently involved violent arguments between the two over the issues of Russian politics. In February 1933 Konstantine flew into a jealous rage at the girl’s apartment (he apparently suspected her of taking another lover) and brutally stabbed her to death. At first Konstantine admitted the murder was the result of a fit of “sexual jealousy,” but later he changed his story and claimed that he committed the act because he had discovered that Maria was a secret Soviet spy (a strong indication of the mental imbalance that would plague both father and son during their middle-age years). The end result of the inexplicable and horrific crime was a sentence of eight years in a prison labor camp.

Just as one door slammed shut on Konstantine’s future happiness in Japan, another seemingly swung wide open on Victor’s own promising prospects. At the very time the tragic occurrences were unfolding in Asahikawa, baseball events were also taking a rather historic turn in central Japan. During the fall months of both 1931 and 1932 prominent Tokyo newspaper publisher Matsutaro Shoriki — seeing the growing Japanese passion for the sport of baseball as fraught with potential business opportunities — had sponsored visits by barnstorming big leaguers who played against local university all-star squads. Embarrassed by the one-sided nature of those games and also determined to establish professional play in his homeland, Shoriki was bent on hiring skilled local ballplayers as true professionals and training them to achieve far better results against the talented Americans.

One of the prominent big leaguers on the 1931 and 1932 barnstorming tours (which also included such luminaries as Lou Gehrig and Charlie Gehringer) was two-time National League batting champion Lefty O’Doul. O’Doul quickly developed a lasting fascination with Japan and established a budding friendship with entrepreneur Matsutaro Shoriki. At Shoriki’s urging O’Doul was soon able to persuade the grandest American star of them all — George Herman “Babe” Ruth — to join the big leaguers’ tour planned for the fall of 1934. The stage was set for events that would launch Japan’s modern baseball era. Shoriki began assembling the best squad he could muster to face Babe Ruth and such fellow stars as Jimmie Foxx, Gehrig, Gehringer, O’Doul, Earl Averill, and venerable manager Connie Mack when they arrived in late November. One of the young players clearly in Shoriki’s sights was Hokkaido’s Russian teenage star Victor Starffin.

As with so many other elements defining Starffin’s life, we find two conflicting accounts providing far different details about the teenager’s abandonment of high-school baseball in Hokkaido for the promise of professional play in the nation’s capital. The first is provided by Richard Puff and suggests that Starffin was forcibly spirited out of his hometown largely against his own wishes and certainly against the desires of local residents. This version of the tale suggests that Shoriki’s agents used some strong-armed persuasion to entice the youngster, who had no desire to leave his high-school squad (where he still had a remaining year of eligibility and still nursed the dream of reaching the prestigious Koshien tournament). It also suggests that fans in Hokkaido were so unwilling to lose a genuine hero that Asahikawa town officials and village residents conspired to sequester the young pitcher and his mother and even assigned them personal bodyguards. As this tales goes, Shoriki’s representatives finally threatened the Starffins (who were now without financial support after Konstantine’s imprisonment and thus subject to deportation) that Victor’s signing with the Tokyo all-stars was the only available means of salvaging their situation. The scales were also tipped, according to Puff, when a promise was made to modify Konstantine’s prison sentence.

Biographer John Berry offers a slightly different account, one in which Victor was reluctant to leave his high-school team but at the same time was embarrassed by his mother’s financial plight (she had been forced to close the teahouse) and by the fact that school officials and teammates’ families were chipping in to keep his family solvent. This version paints Victor as a far nobler figure driven by guilt that his mother had made so many sacrifices to provide him with his new life in Japan. As Berry tells it, Victor himself made the decision to leave Asahikawa under the cover of night with his mother and with Shoriki’s agent, and school officials and teammates didn’t know anything of his departure until they discovered him mysteriously missing a day later. In Berry’s account, Shoriki exerted his influence to have Konstantine’s prison term cut from eight to 4½ years largely as an act of gratitude and not one of coercion.9

The launching of Starffin’s national-level stardom thus coincided with a crucial moment in the growth of Japanese baseball and also with the eventual establishment of a professional league in the nation that would soon become obsessed with the “American” sport. The 1934 Babe Ruth barnstorming tour was well in progress when young Starffin inked his contract with Shoriki (for a 1,000-yen bonus and a 120-yen monthly salary) and joined the squad for the final pair of matches. Victor’s debut came on November 29 in Kyoto when he took the mound for a single inning against the seasoned Americans, some of whom were twice his age (he was 18 at the time). But the size and Caucasian appearance of the new hurler had to be a surprise for the cocky big leaguers, who had been hacking away for two weeks at diminutive and soft-pitching Orientals. Starffin enticed his first opponent, Detroit second baseman and future Hall of Famer Charlie Gehringer, into a weak infield groundout. After walking both Ruth and Gehrig, Starffin then retired two straight, one a strikeout victim. The solo appearance was, on the whole, a resounding success.

Starffin’s presence on the team was amply hyped in the Japanese press, and although he had pitched only a single inning and had joined the squad quite late, as early as the first week of October the Yomiuri Shimbun (Tokyo’s leading daily newspaper) had already promoted Starffin as one of the first 14 prospects selected for the Japanese all-star squad. By contrast, the brief appearance was nothing to brag of when compared to those of future teammate Eiji Sawamura. It was Sawamura who had gained instant fame and lasting immortality during the memorable series. On November 20 in Kusanagi Stadium, the 17-year-old, small-framed righty came within an eyelash of not only authoring the only home-squad victory of the tour but also shutting out the overpowering big leaguers. Young Eiji fanned Ruth three times and at one point struck out Gehringer, Ruth, Gehrig, and Foxx (Cooperstown immortals all) in rapid succession. It was Gehrig’s seventh-inning homer into the right-field bleachers that provided a narrow 1-0 American victory. On that single afternoon Japan gave birth to its first true professional baseball legend.

Encouraged by Lefty O’Doul, the Tokyo club owner changed the name of his fledgling team and even made plans to launch an experimental league built around his own talented nine. Shoriki had envisioned labeling his outfit “The Great Japan Tokyo Baseball Club” but O’Doul lobbied successfully for the shorter moniker of his own big-league team in New York. Shoriki’s plan soon provided the humble beginnings for a thriving and even MLB-rivaling professional Japanese baseball circuit. But while the league was being patched together in 1935 owner Shoriki had to find a way to keep his own promising club in shape and prepared for the domestic seasons now on the horizon. That was accomplished (again with an assist from O’Doul) via a pair of hastily arranged tours through California during the spring and summer of both 1935 and 1936. These extensive barnstorming tours led to some personal complications for Starffin, who ran into problems with US immigration authorities due to the absence of Japanese citizenship or a valid international passport.10 But by the second year the situation had eased a bit, largely due to the publicity surrounding the star Japanese hurler and his 1935 encounters with American authorities. Victor’s immigration problems aside, the Giants enjoyed a most successful pair of California tours. During its first American sojourn the Tokyo club won 93 of 102 contests (mostly against colle and amateur squads); they lost all five games, however, against the more talented Pacific Coast League teams they faced.

It was during the second trip of 1936 that the young pitcher accidentally earned a novel and rather amusing nickname. While attempting to show off his limited English, Starffin had ordered a meal by announcing “I am chicken” — and of course the label quickly stuck with his amused Japanese teammates. The 1935 summer tour also produced a fortuitous collision between two emerging baseball worlds. In one exhibition match with the San Francisco Seals (now managed by O’Doul) Japan’s soon-to-be greatest pitcher faced a budding American icon, Joe DiMaggio. The future Yankee immortal managed one hit in three plate appearances against Starffin.

Domestic Japanese play finally began in the fall of 1936 with a short campaign that was more like a series of tournaments than a true baseball season. The Giants won 18 of the 27 games they played against seven other league clubs and thus claimed the first Japanese championship. The bulk of the Giants’ pitching that first fall was done by Sawamura, who registered a 13-2 mark with a 1.05 ERA while starting all but a dozen of the team’s games. Relegated to the role of infrequently used number-two starter, Starffin logged only 24 total innings and recorded an unimpressive 1-2 ledger (2.63 ERA). The big Russian had to settle for playing in Sawamura’s shadow and hoping for a more substantial role when a full-fledged campaign would open the following spring.

Starffin didn’t have to wait long for his own chance in the spotlight. During four straight seasons at the end of the 1930s the Gaijin hurler emerged as a true national pitching legend. Sharing mound duties across the now expanded season with fellow ace Sawamura, Victor rang up a 28-11 mark in 1937 and an even more luminous 33-5 ledger the following campaign. Sawamura had already hurled the first Japanese professional no-hitter in the league’s brief inaugural season (September 25, 1936) and then followed that up with a second masterpiece in May 1937. Sawamura actually topped Starffin with his own 33-11 ledger in 1937 and boasted a league-best 1.38 ERA (compared with Starffin’s 1.49). Those were years in which the Japanese season was divided into spring and fall segments with the two half-season champions meeting for the overall title in the late fall. If the new league had been initially built around Matsutaro Shoriki’s all-star Kyojin club, that fact hardly meant that the Tokyo team would dominate its top rivals. The Osaka Tigers proved equally potent behind their own ace hurler, Yukio Nishimura (24-6, 1.78 ERA in 1937) and 1937 batting champion Kenjiro Matsuke (.296 with 7 homers and 62 RBI). Osaka in fact won the November playoff titles over the Kyojin team in both the 1937 and 1938 year-end showdown series.

One noteworthy element of these earliest Japanese league campaigns is the fact that while the victory and ERA totals of both Starffin and Sawamura (and Osaka’s Nishimura as well) were seemingly off the radar charts, the strikeout numbers posted by these aces were hardly eye-popping by big league standards. Pitching a 1937 no-hit masterpiece of his own (July 3 versus the Korakuen Eagles), Starffin for all his dominance struck out only 187 batters (despite logging an impressive 312 innings) in the full campaign. During an even more dominant double-season a year later, the totals climbed only to 222 Ks in 356 innings. The explanation for this anomaly was found in the special ambience and style of Japanese baseball. While smaller Japanese hitters belted few long balls, they were experts at putting balls in play. Even in those earliest years the Japanese built their game around a small-ball approach that featured constant bunting (for base hits, sacrifices, and frequent run-scoring squeeze play) and eschewed strikeout-producing wild swinging in favor of opposite-field slap hitting.

Constant structural change defined the earliest Japanese league seasons, with the original 105-game split season already being abandoned by 1939 (the league’s fourth year) in favor of a single summer 96-game campaign. Season number three in 1938 had already been severely impacted by the outbreak of warfare between Japan and China (which actually began in 1937) that caused a dip in the number of split-season games to 75 overall. Sawamura had left the Giants roster in early 1938 for his first patriotic stint of voluntary military service, leaving Starffin as the undisputed staff ace and unrivaled workhorse. With a minuscule 1.49 ERA over his hefty assignment of 350-plus innings, Victor’s 33 victories made up more than half of his team’s entire spring and fall composite total. Such a workload and such skewed numbers in the win column were once again a product of the special features of Japanese baseball structure. It was customary for ace pitchers of the era to draw starting assignments in two of the three weekly games played by each team.

If he had become a legitimate headliner in only two seasons, in the next pair of campaigns Victor became a true legend. His 1939 campaign has to rank as one of the most impressive ever posted by a professional hurler (any league and at any level) in the annals of modern-era 20th-century baseball. With the season expanded to 96 games and the league expanded as well to nine teams, Starffin registered a remarkable 57 decisions (and 68 pitching appearances in his championship club’s 96 outings), posting 42 wins (64 percent of the Giants’ total).11 About the only league honor to escape him was the ERA title (his was 1.73), which fell to Tadashi Wakabayashi of the Hanshin Tigers (1.09). It was also a joyous year off the field of play since that very fall Victor married a fellow Russian immigrant named Lena whom he had befriended a year earlier at the Nicolai Russian Orthodox Church in Tokyo. It was a joyous family occasion for the Starffin clan since Konstantine had been finally released from prison earlier in the year and was thus also able to attend the elaborate wedding celebration.

But there were plenty of storm clouds on the immediate horizon for both the Starffins and the Japanese nation as a whole. The outbreak of worldwide warfare would soon enough send the personal lives and professional careers of pitchers Sawamura and Starffin spinning in radically different directions. Both were destined to meet tragic ends, but it would be two tragedies of far different orders. Sawamura re-enlisted for a second stint in the Japanese military and perished as a national hero during the global war’s final stages. His name was later immortalized with attachment to the Japanese League version of major-league baseball’s Cy Young Award. Starffin’s immigrant status initially protected him against the physical dangers of military service. But the Gaijin hurler in the end paid an almost equally severe price precisely because of his non-native background.

Starffin for his part continued to thrive for a brief while in a Japanese league that marched on during wartime years.12 While the peak seasons of his career had already come and passed during the earliest years of the widening Pacific conflict (the late 1930s), by the early 1940s the towering Russian right-hander was once again a seeming idol, boasting both a beautiful Russian wife and continued soaring professional success. Nonetheless, the war atmosphere was affecting even more severely Japan’s national sport by the dawn of the 1940 season, and it soon impacted even more directly the country’s number-one star pitcher. Politically motivated changes introduced by the Japanese Baseball Association for the 1940 season included the mandating of a whole new set of native Japanese-language terms to replace the imported American-inspired baseball lingo: “play ball” would now be “shiai hajime”; a strike became a “right pitch” (seikyu) and a ball a “bad pitch” (akkyu); dozens of similar improvisations were also added. And team names were also changed: the Osaka Tigers were redubbed the Hanshin Gun or “army,” while the Tokyo Senators morphed into the Tokyo Tsubasa, to cite but two cases. Since the Tokyo Yomiuri Giants were already using the moniker Kyojin (Japanese for Giants) they merely had to replace the English spelling on their uniforms (which looked exactly like that of the New York National League club) with more appropriate Kanji characters.

The biggest name change was reserved for the Giants’ top pitcher. Government officials were becoming increasingly uneasy about the fact that one of the nation’s top sporting heroes not only boasted a Russian or foreign name but also as a 6-foot-plus statuesque blond was a spitting image and constant remainder of two looming foreign enemies, the Russians and the Americans. There was mounting behind-the-scenes pressure to have Starffin simply removed from the Japanese baseball scene; from the late ’30s until the war’s end the Giants ace was kept under constant surveillance as an untrustworthy outsider and perhaps even a dangerous foreign agent or potential spy. Club owner Shoriki was able to fend off outright expulsion but he eventually had to agree to a distasteful compromise with government agents. Starffin, who had already seen his formal application for Japanese citizenship stonewalled, was now required to officially adopt a Japanese name — Hiroshi Suda — if he was to continue his baseball career. An angry Starffin had little choice but to accept the humiliating change. Stories (perhaps apocryphal) circulated that as a quiet act of defiance the proud Russian secretly wore a T-shirt under his game jersey with a V stenciled over his heart.

Further harassment of Starffin came in the form of a mandate to file special applications for permission to travel outside Tokyo whenever the Giants set forth on road trips during those wartime seasons. But as troublesome as it might have been personally, government harassment seemed to have altogether little impact on actual performances by the ace hurler now known as Hiroshi Suda in the Japanese sporting press. The Giants surged to the second of what would eventually be six consecutive war-era pennants in 1940 with an overall 76-28 record and Starffin/Suda again was the club mainstay. The pitcher’s second straight campaign of remarkable numbers stood only a shade below those of a year earlier: 38-12 won-lost record, a massive 436 innings pitched, 245 strikeouts, and a microscopic 0.97 ERA. The spectacular ERA figure was again only second-best in the pitching-rich Japanese circuit (behind the 0.93 posted by Jiro Noguchi of the Tokyo Tsubasa, née Senators) but it nevertheless contains its own remarkable feature. Boasting credible hitting skills, Starffin batted home 22 runs as a slugger, less than half of the mere 49 earned runs he surrendered on the mound. For his remarkable efforts Starffin/Suda was awarded a second consecutive MVP trophy.

While Starffin’s baseball career (and accompanying personal life) did not suffer an immediate collapse after 1940, it did begin a rather dramatic downward spiral. Having labored a Deadball Era-like 894 innings during the previous two seasons, the once physically dominating Russian felt the inevitable effects on his health by the time the 1941 spring season rolled around. Slowed by general fatigue and then a bout with pleurisy, he was able to appear in only 20 games (though his 15-3 record and 1.20 ERA might suggest something far short of complete disintegration). Teruzo Nakao replaced Victor as the Giants’ number-one starter, and Eiji Sawamura also returned on temporary military discharge to register nine wins in the Giants’ fourth straight pennant-winning effort. To add to the on-field setbacks, for a second time Starffin’s hopeful application for Japanese citizenship was rejected, this time with a specific explanation (that he was Russian and furthermore that his father was a convicted murderer). It wasn’t all bad news though, as Victor and Lena welcomed their first child, a son they defiantly named George in honor of American slugger George Herman “Babe” Ruth.13

One week after the late-November close of the 1941 baseball season, the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor and the lives of all Japanese residents — citizens and noncitizens alike — were drastically changed forever. Starffin did rebound with a 26-8 effort during yet another pennant-winning effort for the Giants in 1942, although the Japanese League, just like its American counterpart, showed an immediate dropoff in playing talent and fan support. Many in Japan turned against what was increasingly seen as “the game of the enemy,” and a large contingent of top league stars swapped bats and gloves for military apparel (again just as did their American counterparts). But Japan’s government, like its US enemy, remained every bit as unwilling to admit moral defeat on the home front by canceling the national pastime.

Pressures continued to mount on unwanted foreigner Starffin/Suda while war surged on across the Asian front, and among other embarrassments there was a publicized arrest while eating with teammates in a Tokyo noodle restaurant. This transpired when a waitress alerted police to the presence of foreign-looking potential spy. Pressure also increased on Giants management and by 1944 the ballclub was finally forced to suspend its ace hurler, largely due to fears that a foreigner in the lineup of the country’s most popular team might encourage some government officials to push even more strongly for shutting down the league altogether.

By the outset of the 1944 season the depletion of talent had reduced the skeletal league to a mere six teams. Victor had just burst out of the gate with an early-season unblemished 6-0 mark (and 0.68 ERA) against the reduced opposition when he was given the shocking news that the team was letting him go in the interest of national security. While there is little evidence that Japanese authorities actually saw the longtime resident as a potential spy, he was certainly a thorn in their sides as a public figure and as a celebrity ballplayer permitted to travel freely around the countryside with his touring teammates. With his baseball career apparently over, the Starffins (Victor, Lena, and baby George) were forced to take up residence in the Japanese equivalent of a wartime resettlement camp, in Karuizara, a rural village that was home to other displaced foreigners, including ostensible allies Germans and Italians. In short, the Starffins suffered a fate parallel to that of so many Japanese-Americans on the U.S. West Coast who had been relocated into internment camps. The biggest impact of the move was that Victor’s troublesome pleurisy condition once again returned full force.

And while Victor was suffering ill health in Karuizawa, there were two other significant wartime casualties impacting his life. On November 13, 1944, professional baseball was closed down in the island nation due to the increased threat that American bombing raids on the Japanese mainland were imminent. Three weeks later, on December 2, Starffin’s longtime teammate Eiji Sawamura died when an American submarine sank the Philippines-bound troop transport on which he was a passenger in the South China Sea.

Things didn’t get much better immediately after the war, despite a return to Tokyo following release from semi-incarceration in Karuizawa. Evdokia and Konstantine had remained in Tokyo during the war years but Victor’s father had died there in 1943. Having learned passable English from an Australian during the forced residence in Karuizawa, the former athlete was approached by representatives of the occupying American forces in late 1945 and was briefly employed as an interpreter by a US Army engineering battalion stationed in Tokyo. It was work Victor enjoyed and it also brought a certain renewed prestige, but only a possible return to baseball seemed to brighten any hopes for a more normalized future. When baseball was restarted in Japan Victor approached his old team but was immediately rebuffed despite the fact that he was still under 30 years old and potentially still in the prime of his career. A break nonetheless came when his old manager with the Giants, Sadayoshi Fujimoto, was hired late in the 1946 season by the Pacific club of a newly constituted Japanese League. Fujimoto did not hesitate to offer a roster spot to his old ace. Starffin (now once again proudly playing under his true name) joined the club at season’s end in time to earn a single historic victory, the 200th of his professional league career.

Every upswing seemed to bring a corresponding downturn for Starffin and vice versa. He was not about to escape repeated life-changing upheavals inflicted by a pair of world wars (one that forced his childhood family out of native Russia and a second that wreaked havoc on his adult life in Japan). During the stay in Kazuizawa Lena had become increasingly dissatisfied with her life in Japan and her marriage to Victor. She grew tired of nursing him through his illnesses and blamed his pleurisy attacks on weak mental courage. And after the resettlement in Tokyo she and Victor had a fateful reunion with an old pal from their earliest years at the Nicolai Russian Orthodox Church. Alexander Boloviyov had immigrated to America before the war and now returned triumphantly as a military linguist with the US forces. Lena immediately saw Alexander as her way out of Japan and quickly took him as her new lover. Once his wife had hitched her star to Boloviyov and filed for divorce, the distraught former baseball idol turned to heavy drinking to escape his renewed depression.

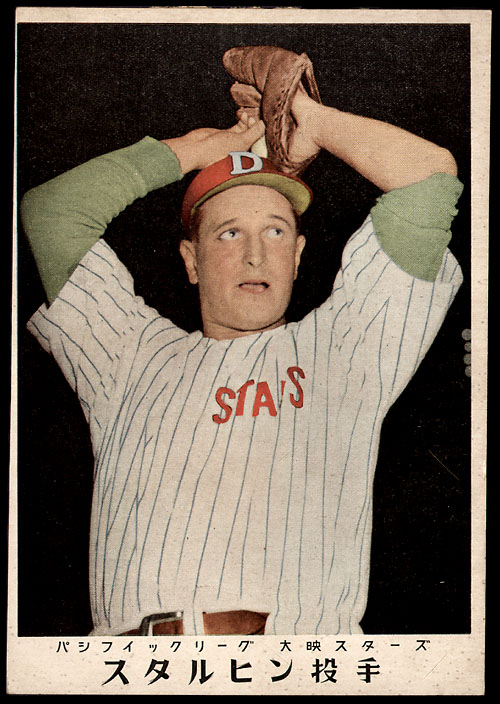

Starffin’s return to professional baseball brought one final glory season in 1949 with his new club (the Kinsei/Daiei Stars, to which he moved in 1948 after pitching in 1947 for the Taiyo Robins). His 27-17 ledger paced the circuit in wins (as did his 376 innings pitched) and his 2.67 ERA was third best in the league. That same fall he faced the barnstorming San Francisco Seals on two losing occasions, shutting out the PCL squad for seven innings on the first occasion and for eight frames on the second. But the long layoff and the alcohol use took their toll and his last six seasons in the early and mid-1950s witnessed a constant downward spiral. There was a final lone appearance against the touring American big leaguers in 1953, a short relief outing in a losing effort against the Eddie Lopat All-Stars. But there was little else to stimulate memories of the prewar glory days for Victor Starffin.

A final high point came in his swan-song 1955 season when he became Japan’s first 300-game winner. The ’50s brought a new era in Japanese baseball (highlighted by a new two-league format), and the sport quickly began to evolve from strictly a pitchers’ game to one featuring more heavy-hitting offense. Fans quickly forgot the old generation of ballplayers, and Starffin as much as anyone had faded rapidly from fans’ collective memories. His quest for 300 victories drew surprisingly little note around the circuit and was played out with minimal attention from the Tokyo sporting press. By 1955 Victor’s team had a new name (the Tombo Unions) and a new corporate sponsor; it was also the worst club in the lesser-quality Japanese Pacific League (winning only 42 games and limping home at the bottom of the pack and 57 games off the pace). Thus there was little interest paid to the game that represented perhaps Starffin’s greatest individual victory. The milestone win finally came against his previous team, the Daiei Stars, and thus also against his old manager, Sadayoshi Fujimoto, the friend who had opened the door for his return in the shadows of postwar occupation a decade earlier.

For all the disappointment of a lost baseball career, one final and more wrenching tragedy lay immediately around the corner. The hopes for another playing contract, or perhaps an alternative opportunity to utilize decades of pitching experience by coaching on the sidelines, met with only further disappointment; no contract opportunities materialized as the months dragged on. Years in the public limelight had brought enough fame to result in a few opportunities for bit movie roles and also a brief stint hosting a popular weekly Tokyo radio music broadcast. But there was little fulfillment and even less money to be found in this handful of celebrity-based odd jobs secured away from the baseball diamond. As 1956 rolled on, Victor’s wife Kunie was accepting part-time hairdressing tasks in order to support her husband and three children. Increased bouts of depression and further escapes into heavy drinking haunted the former star athlete, and, worse yet, Victor began to struggle with the serious episodes of paranoia that had once plagued his aging father. He slept with a baseball bat at his bedside for protection (fearing attacks from intruders) and installed chain ladders on the windows of the family’s second-floor duplex apartment (fearing the outbreak of fire in the family living quarters). He also reportedly would not enter public buildings without thoroughly checking all possible escape routes that might be needed in the case of some cataclysmic unforeseen emergency.14

The slide into psychological illness brought on by alcohol and genetic inheritance did not last especially long. On January 12, 1957, after a night of heavy drinking at a Tokyo location, Starffin rammed his speeding automobile into the rear of an electric streetcar and was killed instantly. The severely depressed ex-ballplayer had left his family behind earlier that evening, supposedly to attend a reunion party of Asahikawa high-school classmates living in the Tokyo area, but he mysteriously never appeared at the event. Later police reports indicated that Starffin was both intoxicated and driving recklessly at the time of the crash, but no one ever determined precisely why he never reached the planned reunion festivities or why he was in the district of the city where the fatal collision occurred. Many in Tokyo at the time speculated that the event was not an accident but rather a successful suicide attempt. Starffin was still nearly four months short of his 41st birthday at the time of his tragic and unexpected demise.

Yet despite the obvious downward tumble that marked the end of his life, Starffin remained an unblemished hero in his boyhood home city of Asahikawa, even if his earlier triumphs had long since faded for many contemporary Japanese baseball fans. Two years after Victor’s death the Japanese Baseball Hall of Fame was established in a location adjacent to Tokyo’s Korakuen Stadium; the initial class of seven inductees included Yomiuri Giants founder and owner Matsutaro Shoriki and former Giants teammate Eiji Sawamura. One year later Starffin himself was admitted into the national shrine that was relocated after 1988 inside the Yomiuri Giants’ new home park, Tokyo Dome Stadium, the nation’s premier baseball palace. When the city of Asahikawa erected a new 25,000-seat baseball stadium of its own in 1983, Starffin received perhaps his greatest posthumous honor: the new facility was named Victor Starffin Stadium (which today remains the only park hosting Japanese League games that is named in honor of a single player), and a bronze statue of the late 300-game winner was placed at the arena’s entrance portals.

Baseball has celebrated its large share of bold racial and ethnic pioneers, none more renowned or decorated than Jackie Robinson. The sport has produced legions of immigrants who have earned their fame and fortune on foreign soil; one has only to recall legions of Latino big leaguers from Cuba’s Adolfo Luque in the early 20th century to hordes of Dominican hurlers and sluggers in the modern era. A large number of diamond stars have suffered truly tragic premature endings to both their on-field careers and post-baseball lives — after the fashions of Ed Delahanty, Roy Campanella, or Luke Easter. But one has to search long and hard to find another professional baseball player whose uncommonly short life span and unevenly celebrated career achievements quite so dramatically combined all these varied elements in a single fortune-blessed yet ultimately ill-starred human being. Among baseball’s truly mythic figures, Victor Starffin may well rank as the most unlikely storybook character of them all.

Sources

Berry, John, The Gaijin Pitcher: The Life and Times of Victor Starffin (self-published, CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2010).

Bjarkman, Peter C., Diamonds Around the Globe: The Encyclopedia of International Baseball (Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Publishing Group, 2005). See in particular Chapter 3: “Japan — Besuboru Becomes Yakyu in the Land of Wa.”)

Johnson, Daniel E., Japanese Baseball, A Statistical Handbook (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland and Company Publishers, 1999).

Puff, Richard, “The Amazing Story of Victor Starffin — A Russian Ace in the Land of the Rising Sun,” in The National Pastime 12 (Cleveland: The Society for American Baseball Research), 17-19.

Whiting, Robert, The Chrysanthemum and the Bat — Baseball Samurai Style (New York: Dodd, Mead and Company, 1977).

Whiting, Robert, You Gotta Have Wa* — When Two Cultures Collide on the Baseball Diamond (New York: Macmillan Publishing, 1989).

Albright, Jim, “Summarized Cases for Cooperstown of Six Great NPB Pitchers,” online article at BaseballGuru.com (http://baseballguru.com/jalbright/analysisjalbright37.html/).

Gillespie, Paul, “Victor Starffin: The Greatest Pitcher in Japanese Baseball History,” online article at fromdeeprightfield.com, December 5, 2011 (from http://deeprightfield.com/victor-starffin-the-greatest-pitcher-in-japanese-baseball-history/).

Notes

1 Puff’s clever observation is provided in the opening lines of his 1992 SABR The National Pastime tribute article (see above references). The Cooperstown case for Starffin (along with five other memorable Japanese League pitchers) is summarized in Jim Albright’s brief but insightful on-line article posted on BaseballGuru.com.

2 My own SABR Biography Project essay on Sadaharu Oh provides details of precisely how universal Japanese racism marked both the high-school career and the celebrated professional sojourn of the man who surpassed the home-run records of both Babe Ruth and Hank Aaron.

3 Whiting’s most detailed discussion of the Japanese baseball “Gaijin phenomenon” is found in Chapter 8 (“Big Fish, Little Pond”), Chapter 9 (“Ugly Americans”), and Chapter 10 (“The ‘Gaijin’s’ Complaint”) of his first (and perhaps best) book, The Chrysanthemum and the Bat: Baseball Samurai Style, 1977.

4 For details of this and other such incidents in Oh’s career, the reader is directed to both my own SABR biography of baseball’s all-time home-run king and also to Oh’s own marvelous autobiography penned with co-author David Falkner (Sadaharu Oh — A Zen Way of Baseball, Times Books, 1984).

5 The classic instance cited by Whiting is the case of Daryl Spencer during the 1965 season (see Whiting, Chrysanthemum, 200-201). Playing for the Hankyu Braves and locked in a battle with Katsuya Nomura for the Pacific League home-run crown down the stretch of the pennant race, Spencer became of the victim of constant intentional walks from the league’s pitchers, even in cases when he came to bat with the bases loaded. The situation became so comical that Spencer began standing in the batter’s box holding his bat at the thick end and waving the bat handle at uncooperative opposing hurlers. Clarence Jones and George Altman were other American sluggers who were victims of similar plots to assure prestigious hitting titles for local Japanese stars.

6 Japan’s six 300-game winners as of 2013 are Masaichi Kaneda (400-298, .573, 1950-1969), Tetsuya Yoneda (350-285, .551, 1956-1977), Masaaki Koyama (320-232, .580, 1953-1973), Keishi Suzuki (317-238, .571, 1966-1985), Takehiko Bessho (310-178, .635, 1942-1960), and Starffin (303-176, .633, 1936-1955). Of the select group Starffin boasted the fewest defeats and the second-best winning percentage.

7 Details on the true date of birth are given in John Berry’s recent biography, the only detailed English-language source on Starffin’s life, and the one based on a Japanese-language biography published in 1979 and written by the ballplayer’s daughter Natasha; Natasha apparently drew her own accounts from family oral history passed on to her by her mother and Victor’s second wife, Kunie. Natasha was only 5 at the time of her father’s accidental death. Although almost all brief published biographies of the athlete, plus all baseball encyclopedia entries in Japan and the United States, list the May 1 date, it is apparently not technically correct.

8 Biographer Berry offers his dramatic account of Evdokia’s separation from Konstantine and her flight into Siberia — including precise dialogue between the pair, highly detailed narrow escapes from various disasters, and the mother’s specific thoughts and fears along the way, as well as her encouragements to her infant child — in a form that resembles a historical novel far more than a precise factual account. The overall thrust of the story, based on accounts handed down orally to Victor’s daughter Natasha from his second wife, Kunie (who obviously got them from Victor himself), may well be true in essence, but the specifics are far more the stuff of historical fiction than of reliable and documented biography.

9 Puff’s version has no documentation while Berry’s is again reportedly based on Natasha Starffin’s account told many years later. There are no known contemporary reports from the Japanese press that might serve as verification. The reader is thus left to judge the truth that probably lies somewhere between these two versions. But both these narrations agree on all the most essential facts: Victor left Hokkaido with mixed feelings and mixed loyalties, local fans and friends were disappointed in his departure, Shoriki’s pro contract relieved the family’s looming deportation crisis, and Shoriki played a direct role in reducing Konstantine’s prison term.

10 Not being a naturalized citizen of his adopted homeland, Starffin had no Japanese passport and thus was immediately held by US immigration authorities in San Francisco. The only paperwork in his possession was a soiled Nansen passport (totally unrecognizable to the Americans) which had been issued to his family by League of Nations officials during their temporary residence in Harbin, Manchuria. The situation was resolved when Pacific Coast League officials and the mayor of San Francisco intervened on behalf of the touring Japanese team and their star player.

11 Starffin’s record 42 wins in 1939 (42-15, 1.73 ERA) has been matched only once, in 1961 by Kazuhisa Inao of the Pacific League Nishitetsu Lions (42-14, 1.69 ERA).

12 There were quite obvious parallels to be found in the decisions of both the American and Japanese governments to keep their “national pastimes” operating during wartime years for reasons of home-front morale. But once the war (in the form of bombing raids) extended into mainland Japan itself the Nippon season of 1945 had to be sacrificed for public safety. And while the American pro leagues returned to almost immediate normalcy with the end of the war, there was a slow rebuilding of the professional game in Japan after the war and during the era of American military occupation.

13 Biographer Berry (obviously drawing on the observations in Natasha Starffin’s earlier work) attributes Victor and Lena’s decision to name their son after two famous Americans (Ruth and Washington) directly to the pitcher’s anger over the several rejections of his applications for Japanese citizenship. In an epilogue to his own book, Berry discusses Natasha’s strong negative opinions about the government abuse suffered by her father.

14 These details of Starffin’s final years are reported in Berry’s biography, The Gaijin Pitcher, which drew heavily on details provided in Natasha Starffin’s personal biography of her late father (Natasha Starffin Ogato, The Dream and the Glory of the White Ball, published in 1979 in Japanese), as well as accounts in a second Japanese biography also based heavily on Natasha’s manuscript (Akira Nakao and Yuko Kunazawa, The Great Pitcher From Russia, 1993). Natasha’s account reportedly contains few baseball details and ends with her father’s signing of a pro contract in 1934; the Nakao-Kunazawa book deals more with Starffin’s baseball life. I did not have access to either Japanese original and therefore have relied here entirely on Berry’s second-hand English-language accounts.

Full Name

Viktor Konstantinovich Starukhin Starffin

Born

May 1, 1916 at Nizhny Tagil, (Russia)

Died

January 12, 1957 at Tokyo, (Japan)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.