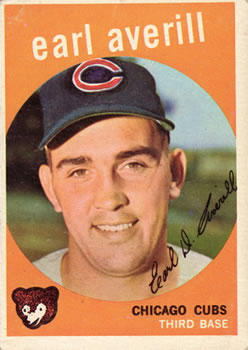

Earl Averill

Earl Averill, a 5-foot-10 catcher and outfielder, compiled a career .242 batting average and had 44 home runs mostly in part time roles over seven major league seasons (1956, 1958-1963) with the Cleveland Indians, Chicago Cubs, Chicago White Sox, Los Angeles Angels, and Philadelphia Phillies. Despite clutch performances, such as walk-off home runs and key RBIs, Averill was a baseball journeyman. In 2003, Averill would say, “I tried to follow in the footsteps of my dad. That was a mistake because there was no following him.”1

Earl Averill, a 5-foot-10 catcher and outfielder, compiled a career .242 batting average and had 44 home runs mostly in part time roles over seven major league seasons (1956, 1958-1963) with the Cleveland Indians, Chicago Cubs, Chicago White Sox, Los Angeles Angels, and Philadelphia Phillies. Despite clutch performances, such as walk-off home runs and key RBIs, Averill was a baseball journeyman. In 2003, Averill would say, “I tried to follow in the footsteps of my dad. That was a mistake because there was no following him.”1

Often referred to as but not actually, “Earl Averill Jr.”, Earl Douglas Averill was the third of four sons of Howard Earl Averill and Loette (Hyatt) Averill and born September 9, 1931, in Cleveland, Ohio. Howard Earl Averill, known as Earl and later Earl Sr., was the center fielder for the Cleveland Indians (1929-39), Detroit Tigers (1939-40) and Boston Braves (1941). The elder Averill was a premier ballplayer of the 1930s and nicknamed, “Earl of Snohomish,” and, “The Rock.” He was selected to the first six American League All-Star teams (1933-38), and, in the 1937 game, hit a line drive off the toe of Dizzy Dean that effectively ended Dean’s career. He was also on the 1934 “All American” Tour of Japan. He was a quiet star compiling 2,019 hits, 401 doubles, 238 home runs and a lifetime .318 batting average.2 In 1975, the Veterans Committee elected Earl Averill Sr. to the National Baseball Hall of Fame, and the Cleveland Indians retired his number 3.3

The Averill family hailed from Snohomish, Washington, a logging town 30 miles north of Seattle. Earl Sr. and Loette married when she was aged sixteen and he was nineteen. She raised four boys, Howard, Bernie, Earl and Lester. The Averill family would split time between Cleveland in the summers and Snohomish in the offseason where the boys were schooled. Young Earl’s first ten years were spent this way. Howard and Bernie occasionally worked as bat boys for the visiting teams and met Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig.4 Bob Feller was known to bounce young Earl on his knee in the clubhouse and later become his teammate.5 After baseball, Earl Sr. and Loette stayed in Snohomish. He worked at Averill Floral, a wholesale florist, with his older brother, Forest “Pud” Averill, and later owned Averill Motel from 1949 until 1971.67

Young Averill made a name for himself around the Snohomish sandlots. More outgoing than his father, he loved to tell stories and play pranks. In high school, Averill played football, basketball, tennis, and baseball. A broken nose in his freshman year sidelined his gridiron ambitions. The Averill brothers were athletically active. Earl and Lester speculated that had World War II and the Korean War not happened, Bernie, who served in the Navy for seven years, would have been a major leaguer. After the Navy, Bernie starred for the University of Oregon at the 1954 College World Series and was a revered teacher and coach at Mercer Island (Washington) High School.8 Lester and Earl bonded as brothers when Lester was bedridden with rheumatic fever for nearly a year in 1940. To keep Lester occupied, they began to build model airplanes together and later flew them. Earl loved the fine detail work.9 His large hands held seven baseballs in one hand long before Johnny Bench made it famous.10 By 1949, Earl was a starting pitcher, catcher, and outfielder and threw a two-hitter to win the Snohomish County championship.11 Earl enrolled at Everett Junior College and led that baseball team to a second-place finish12 In July 1950, he demonstrated power at the plate for the Snohomish Pilchucks with Earl Sr. as manager.13 In 1950, he starred in the annual Seattle Post-Intelligencer youth all-star game.

Earl continued his education, academic and baseball, at the University of Oregon. He bashed his way to being named the Ducks’ first baseball All-American in 1951.14 That fall, he married Patricia “Pat” Allington, high school sweethearts, in Snohomish.15 They moved to Eugene, Oregon and both attended classes. Pat stopped schooling to have the first of four children. Earl finished his studies earning a Bachelor of Arts and a teaching certificate. 16 Averill decided to become a math teacher and had accepted a teaching position at the end of 1952.

Out of the blue, Earl signed with the Cleveland Indians in December 1952.17 He never talked about playing professionally, yet Pat was unwavering in support.18 “I got my great interest in baseball from talking to so many who idolized Dad. I just decided I would never be satisfied unless I, too, gave baseball a try,” he said.19

Earl Sr. thought his son’s powerful swing was suited for Detroit’s Briggs Stadium. The elder Averill had conversations, and reportedly had reached a verbal deal, with Seattle baseball legend and Detroit Tigers manager Fred Hutchinson about signing Earl.20 With both Detroit and Cleveland scouting, Jo-Jo White, scout for Cleveland, arrived first at a planned showcase and Detroit’s scout did not show.21 Earl wanted to be with Cleveland, the team of his father and the town of his birth. He signed for $4,000.22

Cleveland sent Averill to the Reading (Pennsylvania) Indians of the Class A Eastern League in both 1953 and 1954. His big bat (.302 with 16 homers in 563 overall at-bats over two seasons) helped the team reach the league finals in both seasons. His teammates included Rocky Colavito and Herb Score in ’53, and Billy Moran and Hank Aguirre in ’54.23 Averill also played in the 1954-55 Colombian Winter League to hone his skills.24

Spring Training 1955 was solid for Earl. The Sporting News and other publications noticed his big-league potential. It was clear, however, that he was not ready to be a major league catcher and he expected to be sent down to the Indianapolis Indians of the Triple-A American Association.25 He displayed tremendous power but lacked polish at catcher.26 Indianapolis had three catchers on roster, so Earl was shipped to the Nashville Volunteers, a Cincinnati affiliate in need of a catcher, in the Double-A Southern Association.27

Averill quickly learned of the intense rivalry between the Nashville Volunteers and the Chattanooga Lookouts. Rivalry went beyond baseball teams or games. Newspapers in both cities positioned every game as, “Us versus Them.” On July 7, Averill bashed three home runs and two doubles for 16 total bases which broke the 25-year-old Southern Association total base record.28 On a hot, humid August 20 night, the Lookouts hosted the “Vols” at Engel Stadium in Chattanooga. With no love lost between clubs, Vols pitcher Jerry Lane, a former Lookout and Chattanooga resident, amplified the tension. Lane had spent the first month with the Cincinnati Redlegs. At age 29, he had already thrown his last game in the majors. According to Chattanooga press, Lane had a reputation for fire-balling at the heads of batters.29 Lyle Luttrell at age 25, hailed as the Washington Senators shortstop of the future, was in a breakthrough season with Chattanooga. Back from a fractured jaw injury, Luttrell was on a 13-game hitting streak.30 What happened in Luttrell’s second at-bat resonated across the lives of these men for many years, particularly Averill.

During the fifth inning, Lane faced Luttrell with Averill behind the plate. Lane snapped a late breaking slider to Luttrell. Then another. Luttrell responded by moving up in the box. According to Averill, Lane barked, “You can’t step up on me like that.”31 Averill gave Luttrell the same advice. Luttrell remembered Lane’s bark as, “Nobody does that to me. If you, do it again, I’ll stick it in your ear.”32 Another slider for ball three. A fourth slider ran inside with Luttrell up in the box and in front of the plate. The pitch went wide and brushed the back of Luttrell’s pants at the knee. Unhurt, Luttrell responded by throwing his bat with both hands at Lane and stepping toward the mound. Lane jumped to avoid the bat. With Lutrell advancing toward Lane, Averill sprang up, stepped forward and decked Luttrell over his right shoulder. Luttrell fell face first to the ground unconscious. Lookouts’ manager Cal Ermer, coaching third base, rushed at Averill and jumped on his back. Benches cleared. The next five minutes were a free-for-all mele. Players removed shoes to use as weapons. The Lookouts trainer worked to revive Luttrell during the fracas. Chattanooga police entered the field. Chief of Police, Ed Ricketts, in the press box on the stadium roof, ordered for Averill’s arrest. Allowed to shower and dress, Averill was arrested on assault and battery charges. Pat Averill listened to the game on the radio from their Nashville apartment. She remembers, “They kept saying, ‘Luttrell is down. Luttrell is down.’” I had a terrible thought, “I hope Earl has not killed that man.”33

Luttrell revived twenty-five minutes later in the hospital. He suffered a broken jaw, concussion and lost two teeth.34 The only punch Averill threw was the one that clobbered Luttrell as Luttrell advanced toward Lane. Vols manager Joe Schultz said in the aftermath, “I don’t blame Earl. Any catcher in baseball would have done the same thing. It’s part of his job to protect the pitcher.”35 Averill’s worst moment was out in the open. “I lost my temper when he hurled his bat,” said Averill.36 Southern Association suspended Averill for 10 days with a $50 fine.37 Luttrell and Lane went undisciplined. Luttrell responded with a $50,000 civil suit against the Nashville Vols and Averill.38 Averill was recalled to Indianapolis to finish the season.39

1956 spring training provided a fresh start. Cleveland’s training camp in Tucson, Arizona, with its high dry desert air, was a launching pad for Averill’s power. He cranked home runs which earned notice by The Sporting News and other national publications. Manager Al Lopez said that Averill was, “100 percent improved in all ways.” General Manager Hank Greenberg told Averill that he would make the Indianapolis squad.40 Then Averill blasted away during the exhibition trip leading up to Opening Day keeping himself in the competition for the big-league catching job with Hank Foiles.

Averill made the Opening Day roster as backup catcher and made his major-league debut on April 19, versus the Chicago White Sox. Earl Sr. was very proud of the fact that he was just the fourth former player to see his son reach the major leagues.41 His red-hot bat went into an “artic freeze.”42 With only one hit in 18 at-bats, Averill was sent back to Indianapolis. A broken finger limited opportunities to the outfield in his time with Indianapolis; however, he was recalled in June and stuck with Cleveland for the rest of the season.

That winter, Averill homered 15 times to lead the league for Hermosillo in the Mexican Pacific Winter League.43 Spring Training in 1957 did not go as well. Kerby Farrell, Averill’s manager at Indianapolis the year before, was in his first and only season as a major league skipper. Averill felt he was not able to demonstrate his value to the major league club, particularly behind the plate. Farrell had Averill as a reserve with Jim Hegan as starter. Averill did not make the cut and was sent to the San Diego Padres of the Pacific Coast League. He found his stroke batting .273 with 104 hits in 119 games. In May 1957, Earl Sr. would watch Averill play organized baseball for the first time. Earl Sr. gave him advice, “I counseled him always to swing as if he has two strikes on him…Some of the longest homers I ever hit were when I had two strikes and shortened my swing just to keep from striking out.” 44 Earl Sr. was not a fan of the “take to 1” approach stating, “Why are you giving them the first strike?”45 The advice paid off.

In July 1957, matters relating to the Luttrell lawsuit accelerated. A jury found for Luttrell in the amount of $5,000 against the Vols and Averill. The Vols appealed. The judgement was vacated; however, Averill did not appeal and was therefore responsible for the entire $5,000—more than an entire season of minor league salary. Averill with wife and, at the time, two children was put into difficult financial straits. Luttrell’s legal team attempted to garnish wages.46 Averill was unable to purchase a home or a car for his family due to the judgement and interest accrued. There was no support from the Nashville or Cleveland clubs. Pat Averill truly felt that the sport abandoned her husband, and she was not happy with organized baseball.47 Years of financial wrangling ensued which perpetuated life as baseball vagabonds. Finally in 1962, Judge Robert Cannon, an unpaid advisor to ballplayers, learned of the judgement against Averill. Cannon made quiet inquiries and discovered that the Luttrell judgement could be settled for $3,500. He then was able to secure $1,500 from Gabe Paul of the Indians and $2,000 from Gene Autry of the Angels as gifts to Averill.48 Averill and Luttrell settled the matter amicably and with no hard feelings for $3,500 and a handshake. Averill v. Luttrell became an important and cited decision in sports case law. The incident and the eight-year aftermath took its toll and were simply not discussed in the Averill household.49

Russ Nixon beat out Averill at catcher in 1958 Spring Training. Back with the San Diego Padres, Averill had his best minor league season. He was named Pacific Coast League MVP with .347 BA, 24 HR, 87 RBI in 112 games. Ralph Kiner, then San Diego Padres general manager, said, “Averill can become the hardest hitter. He is the best big-league prospect in the Coast League today.”50 Averill earned a mid-season call up to Cleveland. Manager and fellow Oregon Duck Joe Gordon played Averill in 17 games, all at third base. That offseason, contract negotiations with Cleveland GM Frank Lane stalled and Averill and Morrie Martin, both unsigned, were traded to the Chicago Cubs.

Sports Illustrated claimed that Averill was the most important addition to the 1959 Cubs.51 He made the roster and played in 74 games. He hit memorable home runs — often in the clutch. On May 10, in the first game of a doubleheader, he hit his first National League homer in the top of the 11th inning versus the Cardinals. It provided the margin of victory in a 10-9 win. On May 12, Averill entered as pinch-hitter and stroked a walk-off grand slam home run to beat the Milwaukee Braves. He hit another grand slam against the Dodgers on July 22. Averill continued to hit into 1960, but by that July his batting tapered off. The Cubs sent Averill and cash to the Braves for Al Heist. The Braves sent Averill to AAA and then quickly traded him to the Chicago White Sox on August 13.52 Just ever so briefly, for six weeks, the White Sox rostered two “Earls of Snohomish” with Earl Torgeson, the 15-year major league veteran also from Snohomish, Washington and Earl, “Third Earl of Snohomish.” Bill Veeck sensed financial opportunities of the 1960 expansion draft to turn a profit and did not plan on keeping Averill. He was selected by the newly formed Los Angeles Angels for $75,000.53

Averill had his best season in 1961 as a member of the inaugural major league Los Angeles Angels. He played in 115 games and started 78 at catcher. He slugged a team-leading 21 home runs including the first walk-off home run in Angels’ history on May 3.54 Defensively Averill was a liability and finished second in the American League with 44 Stolen Bases Allowed.55 The social life of the Angels ballplayers and their wives was grand, according to Pat Averill. Gene Autry would often host dinner parties for the team and spouses. Ina Mae Spivey, Autry’s wife, was a gracious hostess and Autry, who gave a prized cowboy hat to Earl, loved to socialize with ball players.56

In 1962, Averill was primarily used in left field with only six games at catcher. From June 3-10, Averill put his name in the all-time record book for consecutive plate appearances reaching base at 17. Used as eighth inning pinch-hitter, Averill stroked a two-RBI double versus the Yankees on June 3. Back in action on June 7, Averill went on a tear and continued to reach base in every plate appearance. The mark of 17 still stands in a tie with Frank “Piggy” Ward. Some consider Averill’s record unofficial since there was a fielder’s choice, and he later reached base on an error by Dan Pfister.57 That streak was the highlight of his season.

Averill’s hot bat cooled, and so did manager Bill Rigney’s enthusiasm for utilizing Averill. When he felt he was not playing enough, Averill was impishly playful. In a close game in Detroit, the Angels were up by a run in the bottom of the ninth. The bases were loaded with two out and a full count on Rocky Colavito. Rigney’s stomach was in his throat. Colavito fouled one off, then Averill sidled up to Rigney and let him know 26 lights on the light pole had gone out.58 Rigney blew a fuse. Averill quipped, “How did I know that Rig already counted?”59 After Averill finished with a .219 batting average in 1962, the Angels cooled on him. He was traded to the Philadelphia Phillies for outfielder Jacke Davis.

With the Phillies, Averill, in a backup role, played in only 47 games as a pinch-hitter, left fielder, first baseman, third baseman, and catcher. He was never able to succeed at any given position. Costly errors were atoned with by home runs and doubles. At the end of the season, Averill’s contract was sold to the Triple-A Arkansas Travelers.60 In 1964 there were discussions with the Baltimore Orioles, but Averill signed with Red Sox’s Pacific Coast League affiliate, the Seattle Rainiers. In 1965, Boston switched its Triple-A affiliate to Toronto. After 16 games with Toronto, Averill arranged to stay close to home and play for Seattle, by then affiliated with the Angels. At the end of 1965, Averill had an opportunity to play in Japan. Earl and Pat considered the move but with the children in school and 39 moves in 14 years, they wanted stability for their family. Averill retired from professional baseball.

Averill and his father played together at the first Old-Timers Game in San Diego on August 18, 1972.61 Both Averill’s starred for the Pacific Coast League All-Stars. Randy Averill, Earl’s son then age 13, remembers Casey Stengel in the clubhouse, fresh out of the shower after the game and dripping wet, wearing only a loose bath towel demonstrating Earl Sr.’s swing to Randy and telling him how no one could pitch his grandfather inside because of his swing and power.62

After baseball, Averill put his teaching certificate to work with the Anaheim school district for three years as a math teacher. After teaching, he joined American Research Corporation as an analyst.63 Unsuccessfully, Earl attempted to sign on as an executive with the Seattle Pilots, and successfully joined Claremont Men’s College as Director of Corporate Relations. In 1975, after ten years in southern California, the Averills relocated to Tacoma. “Got to go home. Got to fish,” he told wife Pat. They were all too happy to be closer to family.64 Earl and Pat now had four children, Mike, Carol, Randy and Julie Anne. Mike was drafted by the Boston Red Sox in 1971 and played four seasons in the minor leagues.65 In his retirement, Earl was active in the Major League Baseball Players Association, aiding players who had not been as fortunate as he after their playing days.

Later Earl and Pat started an upholstery business out of their Auburn, Washington home. “For as big as he was, he was very good with his hands,” Pat related. Averill continue to build model planes and had a whole bedroom full in their home. Also, Earl was a great fishing pole and fly maker. His trout flies gained notoriety among his many friends.66

Averill loved people and loved to tell stories. No surprise that he was friends with Dave Niehaus, legendary Seattle Mariners sportscaster. They met in California when Niehaus was with the Angels and carried their friendship back to the Pacific Northwest. Averill embellished often that his consecutive plate appearances record reached on error was committed by Brooks Robinson and it was his only error that season.67 Another repeated embellishment was that he stole Stan Musial’s bats. Averill also claimed to lead the league in 400-foot foul balls. His charm and sense of humor won him many friends.

Earl Douglas Averill, age 83, passed on May 13, 2015, from complications following surgery.68 Two nights later, the Seattle Mariners held a moment of silence in his honor.69

Last revised: June 20, 2022 (zp)

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Randy Averill (son) and Lester Averill (brother) for their input.

Sincere thanks to Pat Averill (wife) for the interview and sharing their baseball life.

This story was reviewed by Malcolm Allen and Bruce Harris and fact-checked by Ray Danner.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted Baseball-Reference.com, baseballalmanac.com and LA84 Foundation Digital Library Collections.

Notes

1 Dan Raley, “Earl Averill – Ex-Big Leaguer, Son of Hall of Famer No Couch Potato in Upholstery Shop,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, August 6, 2003: D2.

2 Baseball-Reference.com, https://www.baseball-reference.com/players/a/averiea01.shtml.

3 Baseball-Almanac.com, Retired uniform numbers in the American League, https://www.baseball-almanac.com/feats/feats10.shtml.

4 Interview with Paul Jackson, colleague and friend of Bernie Averill, February 5, 2022. (Hereafter Jackson interview).

5 “Young Earl Second Averill to Play with Feller on Tribe,” The Sporting News, April 4, 1956: 3.

6 David Eskenazi, “Wayback Machine: The Earl (and Pearl) of Snohomish,” Sportspress NW.com, https://www.sportspressnw.com/2119569/2011/wayback-machine-the-earl-and-pearl-of-snohomish.

7 Glenn Drosendahl, “Averill, Howard Earl (1902-1983),” HistoryLink.org, https://www.historylink.org/File/9513.

8 Jackson interview.

9 Phone Interview with Lester Averill, January 18, 2022 (Hereafter Lester Averill interview).

10 Phone interview with Randy Averill, January 11, 2022 (Hereafter Randy Averill interview).

11 “Averill Tosses 2-Hitter,” Spokane Chronicle, May 24, 1949: 19.

12 Everett Community College Hall of Fame, https://athletics.everettcc.edu/information/hall_of_fame/2018/bios/averill_earl?view=bio.

13 “Averill Named Manager,” Bellingham Herald (Bellingham, Washington), July 14, 1950: 7.

14 University of Oregon, Hall of Fame, Earl Averill, https://goducks.com/honors/hall-of-fame/earl-averill/25.

15 Marriage License, http://www.averillproject.net/showmedia.php?mediaID=4597&medialinkID=3729.

16 Phone Interview with Patricia Averill, January 15, 2022. (Hereafter Patricia Averill interview).

17 Baseball Reference, Earl Averill, https://www.baseball-reference.com/players/a/averiea02.shtml.

18 Patricia Averill interview.

19 Raley.

20 “Another Averill Story Starting on Tribe,” The Sporting News, April 4, 1956: 3.

21 “Voice of the Fan,” The Sporting News, March 30, 1955: 19.

22 Patricia Averill interview.

23 Baseball Reference, Eastern League Standings, https://www.baseball-reference.com/register/league.cgi?id=af825f91.

24 “Young Averill Appears Close Student of Game,” The Tennessean, June 5, 1955: 33.

25 Franklin Lewis, “New Earl Averill with Indians – Son of Outfield Star is Catcher,” The Sporting News, March 16, 1955: 17.

26 Lester Koelling, “The Bullpen,” Indianapolis News, April 9, 1955: 21.

27 Lester Koelling, “Indians Whip Home from 9-3 Road Trip,” Indianapolis News, June 3, 1955: 17.

28 “Earl Averill Jr. Smashes Record,” Knoxville News-Sentinel, July 8, 1955: 12.

29 “Luttrell Injured in Brawl; Nashville Catcher Is Jailed,” Chattanooga Daily Times, August 21, 1955: 1.

30 Wirt Gammon, “Averill Strikes Shortstop in Jaw,” Chattanooga Daily Times, August 21, 1955: 43.

31 “Vol Catcher,” Nashville Banner, August 22, 1955: 21.

32 Bob Weatherly, “Nashville Vols, Send Lyle Bouquet; Luttrell says suit is up to Engel,” Chattanooga Daily Times, August 25, 1955: 35.

33 Patricia Averill interview.

34 Allan Morris, “$5,000 Verdict for Luttrell in Suit Based on Field Fight,” The Sporting News, December 5, 1956: 24.

35 “Nashville Club Named Co-defendant in Suit,” Chattanooga Daily Times, August 25, 1955: 36.

36 “Vol catcher,” Nashville Banner, August 22, 1955: 21.

37 “Averill Is Fined $50, Suspended for 10 Days,” Chattanooga Daily Times, August 25, 1955: 35.

38 “Lookout Star Sues Nashvols for $50,000,” Knoxville News-Sentinel, August 25, 1955: 28.

39 “Averill Back with Indians,” Chattanooga Daily Times, September 2, 1955: 35.

40 Hal Lebovitz, “Rookie Fights for Cleveland Catcher’s Job,” The Sporting News, April 4, 1956: 3.

41 Eskenazi.

42 “Indians Hoping Earl Averill Can Handle Catching,” Daily Times (New Philadelphia, Ohio), March 7, 1957: 12.

43 “Mexican Pacific Coast,” The Sporting News, March 13, 1957: 13.

44 “Averill, Sr., Gives Batting Advice to Son,” The Sporting News, May 29, 1957: 20.

45 Lester Averill interview.

46 John McGrath, “Long before Offerman, there was Averill,” Tacoma News Tribune, August 19. 2007: C6.

47 Randy Averill interview.

48 Red Smith, “Baseball at End of Feudal Era,” Philadelphia Inquirer, December 8, 1967: 43.

49 Randy Averill interview.

50 Dick Beddoes, “From Our Tower,” Vancouver Sun, June 30, 1958: 9.

51 “Chicago Cubs,” Sports Illustrated, April 13, 1959, https://vault.si.com/vault/1959/04/13/chicago-cubs.

52 “Sox buy Earl Averill; Release Bob Rush,” Chicago Tribune, August 14, 1960: 35.

53 Alan P. Henry and David Kritzler, 1960 Winter Meetings: The Missouri Compromise, https://sabr.org/journal/article/1960-winter-meetings-the-missouri-compromise/.

54 “1 Day Until Opening Day,” https://www.halosheaven.com/2013/3/31/4155982/1-day-until-opening-day.

55 Baseball Reference, https://www.baseball-reference.com/leagues/AL/1961-fielding-leaders.shtml.

56 Patricia Averill interview.

57 Paul O’Boynick, “A’s Skid Reaches Six,” Kansas City Times, June 11, 1962: 23.

58 Glenn Schwarz, “Breeze Blows in Arizona – it’s Rigney Talking,” San Francisco Examiner, March 23, 1976: 45.

59 Ross Newhan, “Analyst Averill Misses His Angel Days,” Los Angeles Times, June 11, 1968: 11.

60 “Phils Recall Six Players from Farms,” Evening Sun (Hanover, Pennsylvania), November 6, 1963: 17.

61 “Old-Timers Game Coming Aug. 18”, Star-News (Chula Vista, California), July 9, 1972: 14.

62 Randy Averill interview.

63 Newhan.

64 Patricia Averill interview

65 Baseball Reference, Michael Averill, https://www.baseball-reference.com/register/player.fcgi?id=averil001mic.

66 Lester Averill interview.

67 Randy Averill interview.

68 Dave Boling, “Earl Averill is Gone, but his Stories, Smile Live on,” Tacoma News-Tribune, May 15, 2015: B1.

69 Adam Jude, “Ex-Major League and Snohomish Star Earl Averill Jr. Dies,” Seattle Times, May 14, 2015, https://www.seattletimes.com/sports/mariners/ex-major-league-and-snohomish-star-earl-averill-jr-dies/.

Full Name

Earl Douglas Averill

Born

September 9, 1931 at Cleveland, OH (USA)

Died

May 13, 2015 at Tacoma, WA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.