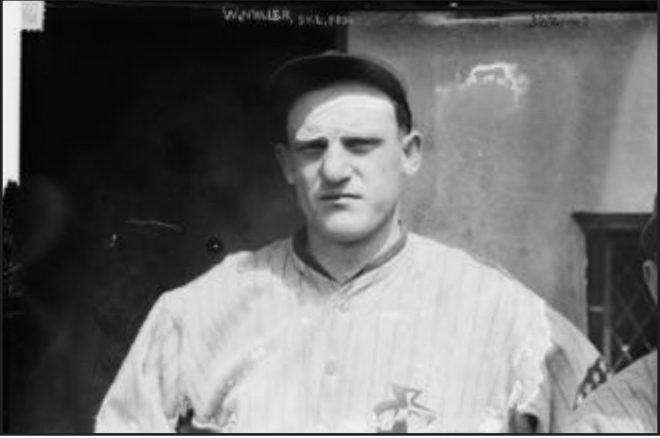

Ward Miller

His baseball career spanned the minor leagues, the National and American Leagues, and even the renegade Federal League, all in an age often referred to as the Deadball Era. Ward Miller, a left-handed-hitting, right-handed-throwing outfielder from Illinois, was never the best player on his team, but he was sufficiently skilled to cobble together an eight-year career in three major leagues and seven more in the minors, all while playing with and against some of the legends of the game. From the outset, in his rookie campaign with Pittsburgh and Cincinnati in 1909, he shared the field with Honus Wagner and Fred Clarke, and played with the eventual World Series champion team (Pirates). He played professionally until 1920, and then walked away from the game. Ultimately, he became a sheriff and civil servant in his hometown of Dixon, Illinois, and lived out a quiet, productive life. He never won a championship or a batting crown, but his career is most certainly one more colorful tile in the great mosaic that is baseball, and American, history.

Ward Taylor Miller was born on July 5, 1884, in Mount Carroll, Illinois, the first child of Martin Luther Eitemiller (the name shortened to Miller when Martin’s family emigrated from Germany) and Rose (Evans) Miller. Martin was a carpenter and moved his wife from their original home in Pennsylvania to western Illinois after post-Civil War Reconstruction. The Millers had four more children, including daughters Jessie and Frances and sons Charles and Harry. In 1900 Ward moved to nearby Dixon, Illinois, to take a job at a shoe factory. In addition to his daytime occupation, he played baseball for the company squad as well as football for the amateur Dixon Athletic Football Club. In 1902, in fact, he won a state championship as an offensive back for the Dixon “Hook-and-Ladder” team. It was from his football exploits that he earned one of his two lifelong nicknames, Windy. Local reporters, in describing his running speed as an offensive end, tacked the sobriquet on him. His other nickname, Grumpy (or Grump), reputedly came from teammates in Chicago because of his reportedly gruff personality.1

While many sources aver that he attended college, either tiny Dixon College in his hometown or Northern Illinois University in one of its earlier iterations, there is no documentary proof that he did so.2 In fact, his daughter Shirley, who died in 2010, told researcher Mark Stach that Miller did not attend college.3 It is anecdotally asserted in later comments by people who were not alive during his college-age years, that Miller did play baseball at Dixon. In Miller’s case, though, there is no tangible evidence that he took the field for his institution. Miller did play several positions for his hometown team, the Dixon Browns, however, and was so adept at both pitching and catching that he and batterymate Jode Whipple would traveled out of state to play-for-pay with semipro squads.4

In 1904 Miller married Ella May Whipperman, also from Dixon, and in 1905 she gave birth to a son, Joseph. They had two more children, including Doris, who was born in 1907, and Shirley, in 1910. Shrley lived for nearly 100 years before passing away in 2010.

Miller’s life changed in 1906, when at 21 he signed with Rock Island, in the Three-I League. Miller later recounted that he might have signed in 1904, except that that year he’d been goofing around, imitating shot-putters, and hurt his shoulder in the process. It took two years for him to regain the strength in his throwing arm. Miller never played for Rock Island, but was instead traded to Fort Dodge in the lower, Class-D Iowa State League. Finally, after those machinations, he landed with the Waterloo Microbes (Iowa State League), and his playing career began in earnest. In his first 70 games as a professional with Waterloo, Miller batted .278, and the next two years were spent with Madison and Wausau, respectively, before the Cubs signed him in 1909. The team placed Miller on waivers with the intention of sending him to Milwaukee for the rest of the season, but Pittsburgh claimed him instead.5

On April 14, 1909, Miller made his major-league debut, against the Cincinnati Reds. He led off the game, played center field in a fairly potent lineup, and hit a triple off Art Fromme in a 1-for-4 effort that supported the 3-0 Pirates victory. Between Opening Day and April 28 Miller played in 15 games, getting eight hits in 58 at-bats. The Pirates were en route to a 110-win season and a World Series title. With an outfield that already included a future Hall of Famer in player-manager Fred Clarke, along with Tommy Leach and slugging Owen “Chief” Wilson, Miller was a trade chip.

On May 28 the Pirates traded Miller and some cash to the Cincinnati Reds for outfielder Kid Durbin. Miller hit .310 in 43 games for the Reds the rest of the way. After an unimpressive campaign in 1910, in which he played only 81 games for the Reds, Cincinnati sold his contract to Montreal of the Class-A Eastern League. With Montreal in 1911 Miller enjoyed what was perhaps his finest season in professional baseball, batting .332 and leading the league in hits with 191. Miller’s season was enough to entice the Chicago Cubs to sign him for the 1912 season, and the outfielder rewarded his new team with a .307 batting average in 86 games.

One advantage of playing with the Cubs, and becoming friends with Frank Chance and Joe Tinker, was that Miller was able to persuade the team to play an exhibition against his hometown Dixon All-Stars. On October 23, 1912, the mighty Cubs came to tiny Dixon. Miller played center field for Chicago that afternoon, and contributed a double and scored a run as the visitors beat the hometown squad, 4-0.6 Based on the absence of anything contrary in subsequent game accounts, it is possible, if not likely, that the contest was the final time that the legendary infield of Tinker, Johnny Evers, and Chance took the field together in an organized game.

The 1913 season proved to be a bit more problematic, however, as Miller saw his offensive performance decline in just about every category, and he served mostly as a fill-in in all three outfield positions. There was one significant bright spot, however. On July 22 Miller hit the first home run of his major-league career, a shot off Grover Cleveland Alexander at the Baker Bowl in Philadelphia.

Perhaps seeking a more secure situation, Miller signed with the St. Louis Terriers of the upstart Federal League before the start of the 1914 season. In 121 games, he collected 118 hits and stole 18 bases while playing all three outfield positions and batting .294. Despite a roster that included Mordecai Brown, the Terriers won only 62 games, and finished in eighth and last place in the standings, 2½ games behind the Pittsburgh Rebels.

The next season, 1915, Miller batted .306 against the Federal League pitching and stole 33 bases in a 154-game campaign. Subsequent analysis established that his WAR was 3.0 wins above replacement level, a mark that put him in 10th place in the league that year. He also finished in the league’s top 10 in hits (164/sixth place), runs scored (80/ninth), and runs created (81/eighth).7 Under manager Fielder Jones, the Terriers jumped to second in the Federal League standings, finishing the year one one-thousandth of a percentage point behind the champion Chicago Whales (.566 to .565).

It was, by any measure, a terrific year for the 30-year-old, but the Federal League folded after the season. On February 10, 1916, the St. Louis Browns purchased Miller’s contract, along with those of 10 Terriers teammates, and so began the American League phase of his career. Miller played 146 games, mostly in right field, for the Browns in 1916, but the team finished 12 games behind the Red Sox, a team that rolled out a roster of starting pitchers that included Carl Mays, future Hall of Famer Herb Pennock, and a 21-year-old pitcher who won the 1916 American League ERA title, George Herman “Babe” Ruth. Miller batted .266 and stole 25 bases. That was his last truly effective season in professional baseball.

In 1917, still with St. Louis, Miller played in only 43 games, hit .207, and was used almost exclusively as a pinch-hitter. He made his final major-league appearance on July 15, 1917, against the Red Sox. Miller went 1-for-3 at the plate, with a stolen base, but his big-league career was finished. On July 19 Miller and pitcher Jim Park were released to Omaha of the Western League. Miller apparently refused to report to Omaha.8 Miller’s bottom line included 769 major-league (National, American, and Federal Leagues) games, a .278 batting average, and 128 stolen bases. His lifetime WAR was a respectable 9.3.

In 1918 Miller caught on with the Salt Lake City Bees in the Pacific Coast League, and then played two final seasons with the Kansas City Blues. Even at the relatively advanced age of 34, he managed to hit .318 in the American Association in 1919. After a final season with the Blues in 1920, though, Miller retired from baseball and returned to his wife and family in Northwest Illinois. He played baseball for a few years with the local American Legion team, but shifted his focus to life after baseball. Miller served two terms as the Lee County sheriff, one term as chief deputy sheriff, and a term as Lee county treasurer. He also maintained an active interest in sports leadership. In the 1930s he was president of the Rock River Valley League and a member of the National Softball Association’s rules and players committees. His final job was as chief of cecurity at the Dixon State School.9

Ward Miller died on September 4, 1958, at the age of 74. He is buried in the Oakwood Cemetery in Dixon.10 In August 2011 a group of citizens and regional baseball historians gathered at the Lee County Courthouse in Dixon for the dedication of a monument to Miller. For a moment, the assembly remembered the great players with and against whom Miller played, and his contribution to the community well after his playing career ended.

Notes

1 Interview with Mark Stach, and his recollection of Miller’s youngest daughter’s recollections of her father, May 13, 2018.

2 https://baseball-reference.com/players/m/millewa02.shtml; https://baseball-almanac.com/players/player.php?p=millewa02.

3 Mark Stach interview.

4 Dixon (Illinois) Evening Telegraph, July 10, 1903: 9; Dixon Evening Telegraph, August 24, 1905: 5.

5 Norm Jollow, “What’s Th’ (the) Score,” Dixon Telegraph. Article is an undated clipping maintained in the Miller family archives.

6 Dixon Evening Telegraph, May 1, 1951: 152.

7 All rankings are drawn from baseball-reference.com/players/m/millewa02.shtml. There are other methodologies for evaluating player performance, but they tend to calculate approximately similar values, and Baseball-Reference is the most easily accessed for verification.

8 Daily Chronicle (De Kalb, Illinois), July 21, 1917: 4.

9 Dixon Telegraph, November 1, 1996.

10 https://sabr.org/latest/ward-miller-monument-dedicated-in-dixon-illinois.

Full Name

Ward Taylor Miller

Born

July 5, 1884 at Mount Carroll, IL (USA)

Died

September 4, 1958 at Dixon, IL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.