Will Clark

There may have never been a more prepared baseball player to enter the professional ranks than Will Clark. He had participated in World Series competition at the Babe Ruth, American Legion, and Division I College levels, as well as the Olympics. During his first five major-league seasons starting in 1986, he helped restore the San Francisco Giants organization to prominence. He became a highly-regarded player and was rewarded by being the highest-paid player in baseball early in his career. But nagging injuries eventually became problematic for him, reducing his offensive production in his later years with the Giants and then with Texas and Baltimore.

There may have never been a more prepared baseball player to enter the professional ranks than Will Clark. He had participated in World Series competition at the Babe Ruth, American Legion, and Division I College levels, as well as the Olympics. During his first five major-league seasons starting in 1986, he helped restore the San Francisco Giants organization to prominence. He became a highly-regarded player and was rewarded by being the highest-paid player in baseball early in his career. But nagging injuries eventually became problematic for him, reducing his offensive production in his later years with the Giants and then with Texas and Baltimore.

Clark developed a persona on and off the diamond that was described as dramatic, cocky, brash, loud, flamboyant, intense, gamer, aggressive, and temperamental. He wore his emotions on his sleeve, but no one expected more of him than he did of himself. It was during his early Giants games that he got tagged with popular nicknames like “The Thrill” and “The Natural” by his teammates. He even became well-known for his facial expression that was characterized by an intense, competitive scowl and big swaths of eye-black on his cheeks.

William Nuschler Clark, Jr. was born on March 13, 1964. He grew up in the Gentilly area of New Orleans, living near Digby Playground where he first played baseball at eight years old. Initially baseball was just something that he played for six weeks during the summer.1

Clark’s love of sports came through his father’s interests as an avid hunter and fisherman. He similarly developed a devotion to outdoor sports, an activity he would continue to enjoy later during his major-league offseasons.2 He grew up in a tight-knit family that included his father William Nuschler Sr., mother Letty Jane (Hubert), brother Scott, and sister Robin. Both of Clark’s parents were natives of New Orleanians.3 His father was a sales manager for a pest control company; his mother was a dietician for the local school board.4

When he was 15, his Babe Ruth team finished third in the national World Series in 1979.5 A sophomore in 1980, his Jesuit High School baseball team won the Louisiana state championship, and the Jesuit-based American Legion team took third place in the World Series that year. As a junior, Clark surpassed New Orleans native Rusty Staub’s season home run record for Jesuit High by smacking 10 home runs in 14 games.6

Clark was selected by Kansas City in the fourth round of the 1982 draft, but spurned a $35,000 bonus offer from the Royals because he felt he wasn’t mentally or physically mature enough. Instead, he committed to play baseball at Mississippi State University. 7

He teamed with Rafael Palmeiro in his sophomore season at Mississippi State to form one of the best one-two punches in the Southeastern Conference. Their hitting prowess earned them the nickname “Thunder and Lightning.” In the 1984 Olympics in Los Angeles, Clark was the leading hitter on the USA team that won the silver medal as a demonstration sport.8 As a junior in 1985, he led Mississippi State to the College World Series, was named the top college player of the year, and was drafted second overall by the San Francisco Giants.

Assigned to Fresno in the Class-A California League in 1985, he smacked a home run in his first pro at-bat

Clark was invited to the Giants’ spring training camp in 1986 as a non-roster player, although he wasn’t expected to make the big-league club. However, once he got into the Giants’ lineup during exhibition games, manager Roger Craig couldn’t find a good reason to take him out. In his first game in a Giants uniform on March 7 against Oakland, he drove in four runs with a home run and a double.9 Clark wound up beating out 14-year veteran Dan Driessen for the starting job, as Craig couldn’t ignore Clark’s .297 batting average and five home runs during the spring camp.10

Craig expressed confidence in his decision, “He had done everything we’ve asked and he has major league written all over him. Sometimes it takes six or eight weeks to find out about a young man’s ability, but we think he’s ready to step in and play first base now.”11

Clark proved his manager’s instinct was correct. His major-league debut occurred on April 8, 1986, against the Houston Astros in the Astrodome. In his first plate appearance, Clark faced career strikeout leader Nolan Ryan in the first inning. On Ryan’s third pitch and Clark’s first major-league swing, Clark deposited a letter-high fastball into the center field bleachers, 420 feet away. He became the 50th player in major-league history to hit a home run in his first plate appearance. With a flock of Clark’s family and friends from New Orleans attending the game, the Giants won, 8-3.12 Clark would go on to have great success against Ryan during his career. In 39 plate appearances against Ryan, he belted six home runs, drove in 11 runs, and posted an OPS of 1.274.

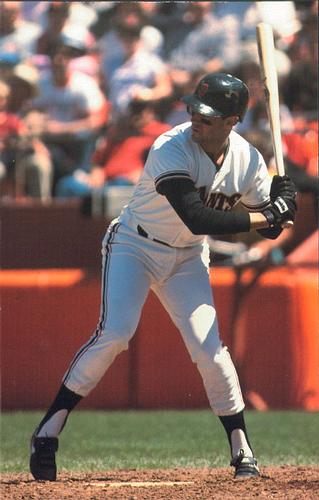

Clark arrived on the pro scene with a smooth, natural swing that a Sports Illustrated article described as “the sweetest swing anyone had ever seen, an uppercut with a long, loopy follow-through that made it seem as if he was wielding a buggy whip instead of a 32-ounce bat.”13 Hence, the nickname “The Natural” became associated with him.

His classic hitting style and concentration at the plate conjured up recollections of legendary hitters Ted Williams and Stan Musial by some of the former big-league players who were around during their careers.14

Within his first four seasons, Clark established himself as a bona fide star in the big leagues. In 1987 he helped propel the Giants to their first division championship in 16 seasons. He became an All-Star selection and led the National League in RBIs in 1988. In 1989 he was runner-up for NL MVP and was instrumental in the Giants winning their first pennant since 1962. The Giants leveraged his instant popularity by making him the subject of a Bay Area marketing poster displaying the slogan “I’ve Got a Giant Attitude.”15

The fanfare that accompanied Clark’s first few months, along with his brashness and confidence, drew mixed reactions from his teammates. Veteran catcher Bob Brenly gave him the nickname “The Thrill” for his early heroics. Clark knew he had gained a measure of respect from his teammates when they painted his favorite cowboy boots orange, only to give him a replacement pair later. 16 On the other hand, some of his other teammates didn’t know how to take Clark’s demeanor. His boldness caused some animosity.17

Clark incurred the first of his many career injuries during his rookie season when he collided with Montreal Expos first baseman Andres Galarraga and suffered a hyper-extended elbow that kept him on the disabled list for almost two months.18 He still finished fifth in the voting for National League Rookie of the Year.

With the addition of Kevin Mitchell in early July 1987 to complement the hitting of Clark, Jeffrey Leonard, and Candy Maldonado, the Giants took over sole possession of first place by August 21 and never relinquished the lead, winning their first division title since 1971.

At one point in the season, Clark hit eight home runs in 11 games and had nine consecutive games with an RBI. He was named NL Player of the Week twice during the season. He finished the regular season with a slash line of .308/.371/.580 and led the Giants with 35 home runs and 91 RBIs. Clark attributed his stats increase to being able to avoid injuries and to sustain his strength late in the season, aided by the conditioning he had done with New Orleans fitness guru Mackie Shilstone over the winter.19 In only his second major-league season, Clark was fifth in the NL MVP voting won. Clark was named the Giants team MVP.

The Giants faced the St. Louis Cardinals in the National League Championship Series and held a 3-2 lead after Game Five. However, the Cards shut out the Giants in the final two games to claim the pennant. Clark hit .360 for the series.

Despite his overall success in his first couple of years with the Giants, he would sometimes agitate his teammates by throwing temper fits after poor at-bats, throwing his helmet, or slamming the bat rack. He said his grumblings after poor performances were misunderstood by his teammates.20 Kevin Mitchell said about Clark, “Some people don’t like Will because he talks a lot.” But Mitchell was quick to add, “If you don’t hear Will, something’s wrong.”21

Manager Roger Craig observed about Clark in the spring of 1988, “He’s got a lot of growing up to do. I’ve talked to him quite a bit about that. He does a lot of things he’s sorry about later.” 22 On the other hand, Craig noted about his star player, “I regard a lot of our guys as indispensable, but if I had to pick one, it would be Will Clark. In addition to his natural ability, he has the charisma that puts people in the park.”23

The 1987 season naturally brought increased expectations for Clark in 1988. Yet no one had higher expectations than Clark himself. He began to draw comparisons with Mark McGwire, the prolific power hitter for the Oakland A’s.

Clark made his first All-Star team in 1988, beating out Keith Hernandez and Andres Galarraga. At the break, he had a .386 on-base percentage and was leading the National League with 68 RBIs.

Clark began winning the admiration of his peers and opponents for his confidence at the plate. In an interview with The Sporting News in July 1988, Chicago Cubs manager Don Zimmer commented about Clark, “The thing about it is, the guy knows he can hit. A lot of people on the other side will look at Will Clark and see that he’s got a few mannerisms, he’s got a little cockiness about him, so they don’t like him. But they would have to know Will Clark like I do to appreciate him.”24

New York Mets first baseman Keith Hernandez offered this assessment of Clark: “There’s no question Will and (Andres) Galarraga are the next two standouts at first base. Will seems to have a real good knowledge of the strike zone, and he doesn’t swing at many bad pitches. I don’t see cockiness in him. I see youthful exuberance. You like to see that in players.”25

Giants broadcaster, Hall of Famer Joe Morgan, said of Clark, “He carries his personality to the plate. He just knows he’s going to get a hit.”26

He led the National League in RBIs (109), walks (100), and intentional walks (27) and finished with a .282 batting average and 29 home runs. He had the highest RBI total for a Giants player since Willie McCovey (126) in 1970. For the second year in a row, Clark finished fifth in the voting for NL MVP and repeated as the Giants’ team MVP. Despite Clark’s efforts, the Giants had a significant drop-off from their division title the year before, finishing fourth in the NL West with an 83-79 record.

Clark and Mitchell got off to sizzling starts in 1989. The Giants’ power duo quickly earned the nickname “Pacific Sock Exchange” in the Bay Area.

Clark and Mitchell got off to sizzling starts in 1989. The Giants’ power duo quickly earned the nickname “Pacific Sock Exchange” in the Bay Area.

Clark said, “I’ve never had a start like this. I’d attribute it to a lot more work this winter. I just felt there were some things I had to do to improve, so I doubled my batting practice. The weather in New Orleans was good, so that helped.” With regard to his production with Mitchell, he added, “They’re still pitching carefully to me. But now it’s more likely to hurt them. It’s the same as it was with Rafael Palmeiro and me at Mississippi State. If one guy didn’t do it, the other guy would.”27

Hitting experts marveled at Clark’s natural swing. Giants’ batting coach Dusty Baker commented, “Will’s main asset is a tension-free swing. He doesn’t muscle the ball like most power hitters. Will uses leverage extremely well. He’s a hitter, not a slugger, and what he’s doing now shouldn’t come as a surprise.”28

Clark gave credit for his hitting mechanics to Barry Butera, a New Orleans-based coach and former Boston Red Sox minor-leaguer. Clark told The Sporting News, “I was a dead pull hitter in high school, but my swing was revamped by Barry Butera, who was a Ted Williams disciple. We placed a lot of emphasis on leverage and using the hips, because I wasn’t big and strong. I’m not a hacker, so my success is based on a fluid swing, bat speed, and perfect contact.”29

Clark led the All-Star voting; at the break he was hitting .332 with 14 home runs and 64 RBIs. The Giants were leading the Houston Astros by two games in the NL West.

Clark battled San Diego’s Tony Gwynn for the batting title for most of the season. The competition came down to the last two games of the season against each other in San Diego. On September 30, Gwynn went 3-for-4 to move within a percentage point of Clark, .333 to .334. The next day Gwynn repeated his 3-for-4 performance to finish at .336 and win his third straight title. Clark, who was booed heavily by the Padres’ home crowd, managed to get only one hit in four at-bats to end up in second place at .333.

The Giants had taken sole possession of the NL West on June 17 and never relinquished the lead for the remainder of the season. They finished with 92 wins, three games ahead of the Padres.

San Francisco faced the Chicago Cubs in the National League Championship Series. Clark had one of the best-ever series in major-league playoff history, as the Giants had an easy time with the Cubs, winning the series, 4-1.

Clark had a perfect day at the plate in Game One, garnering four hits in four official at-bats and drawing a walk. He scored four times and drove in six runs, practically single-handedly defeating the Cubs. He homered twice off Greg Maddux, including a grand slam in the fourth inning that effectively put the game out of reach for the Cubs. After the game, Clark downplayed his performance, “Anything can happen in a seven-game series. I just got locked in a groove, but it doesn’t mean I have this park or the Cub staff in my pocket.”30

But Clark would indeed have Cubs pitchers in his hip pocket during the rest of the Series. He continued his torrid hitting, winding up with 13 hits and two walks in 22 plate appearances in the five games. He compiled a whopping 1.882 OPS for the series. His 11 total bases in Game One were a record at the time. He was the clear choice for MVP of the Championship Series.

The Giants advanced to play Bay Area rival Oakland in the World Series, the Giants’ first appearance since 1962. Oakland was coming off its second consecutive American League pennant, despite having slugger Jose Canseco for less than half the season due to injuries.

The A’s made quick work of the Giants in the first two games of the Series at their home stadium, as the Giants’ bats were dormant in 5-0 and 5-1 losses.

The Series moved to Candlestick Park, and what followed in Game Three on October 17 was one of the most bizarre events in World Series history, although not because of what occurred during the game. Just minutes before the contest was to begin, a magnitude 6.9 earthquake struck the Bay Area and lasted 17 seconds. Game Three was cancelled, and out of safety concerns, the Series was postponed indefinitely by Commissioner Fay Vincent.31

The stadium was eventually approved to resume the Series, once cracks in the upper deck structure were repaired, and Game Three was played on October 27 in San Francisco. Although they generated more offense than the previous two games, the Giants could never seem to get ahead of the A’s pitching and wound up losing, 13-7, in Game Three and 9-6 in Game Four. Clark came off his postseason high with only four hits in 16 at-bats during the four games.

Mitchell bested Clark for the National League MVP Award, as he led the league with 47 home runs and 125 RBIs. However, Clark enjoyed a well-rounded season, ranking first in runs scored (104), second in batting average (.333), second in hits (196), third in RBIs (111), third in triples (9), fourth in doubles (38), third in slugging percentage (.546), and third in on-base percentage (.407). He also hit 23 home runs.

Clark had done practically everything possible in 1989 to position himself for his next contract negotiation over the winter. His dramatic five-game performance in the NLCS put him into a new level of public awareness as a superstar. Even his mediocre World Series performance didn’t diminish his value as a player, nor his overall market value.

Clark’s standout season couldn’t have come at a better time from a financial standpoint. In January 1990, the Giants made him the highest-paid player in history with a four-year $15 million contract. The contract averaged $3.75 million per year, including a $2 million signing bonus, the largest ever given to a major-league player.32 Obviously pleased with re-signing Clark, Giants GM Al Rosen told The Sporting News, “Will Clark is the premier player in the game and he earns every cent. He plays like a Hall of Famer, and he should be paid like one.”33

Clark finished the 1990 season with a .295 batting average, 19 home runs, and 95 RBIs. For most major-league players, it would have been considered a successful season. But it was subpar for him, especially when compared to 1989. He had 52 fewer total bases, while his on-base percentage dropped 50 points. During an 84-game stretch from June 11 to September 17, he produced only three HR and 35 RBIs.

There were questions about whether his new record-setting contract had affected his performance. However, Clark insisted money had nothing to do with his drop in performance, but rather the new way opponents were pitching to him. He said, “I’m seeing sliders on the black and nasty split-fingers.”34

However, it wasn’t until the final road trip of the season that Clark revealed that a problem in his left foot, a condition called Morton’s neuroma, had hampered him all season. The ailment forced him to constantly hit to the opposite field. He said he had concealed the problem because he didn’t want to use it as an excuse for his decline. The condition had begun in spring training and continued to worsen.35

The following spring he explained, “This was something I could go out there and play with and make some adjustments to alleviate the pain. We were in a pennant race. I wasn’t going to say anything about it. The trainer knew, but he was the only one who needed to know. I didn’t need sympathy. I just wanted to go out and play.”36

Clark had surgeries during the offseason to address the foot problem and remove his bothersome tonsils. During spring training in 1991, the foot surgery appeared to have worked, as Clark was pulling the ball to right field again with no issues, thus enabling him to raise his home run output.37

By the 1991 All-Star break, he raised his average to .295 to go along with 15 home runs and 59 RBIs. He was selected to his fourth consecutive All-Star Game and got a single and a walk in the National League’s 4-2 loss.

By mid-August the Giants climbed to within six games of the NL West-leading Los Angeles Dodgers. Clark and teammates Kevin Mitchell and Matt Williams were all having good years for home runs, with each considered a candidate to take the league’s home run crown.

However, more than capturing the home run title, Clark was interested in winning the Gold Glove Award for first basemen. He told The Sporting News in mid-August, “You can have all the offensive awards there are. I want the defensive award. I want the Gold Glove.” At the time, he had made only three errors.38

Clark was named the National League Player of the Month for August, when his slash line was .347/.408/.678, with 41 hits, 14 doubles, seven home runs, and 28 RBIs. His production put him in discussions for the Triple Crown and NL MVP.

However, when he fouled a ball off his kneecap in early September, it affected his productivity. During his last 27 games, Clark had only three HR and 14 RBIs and batted .253.

The Giants took a nosedive to finish the season in fourth place, 19 games out. They took some solace in the season when they won two of three games with the Dodgers during the final series of the season to allow the Atlanta Braves to capture the division title by one game. The Giants’ 75-87 record was their worst since Clark had arrived.

He didn’t win the Triple Crown or the MVP Award (he finished fourth), but he did collect first-time hardware for the Gold Glove Award. Also a Silver Slugger Award winner, Clark concluded the 1991 season with a .301 average, 29 home runs, and 116 RBIs. He led the league in total bases and slugging percentage.

Clark entered the 1992 season thinking his best year may be ahead of him; he told USA Today Baseball Weekly, “I haven’t had my career year. I’ve had some very consistent years, where I’ve hit a lot of home runs. I’ve had years where I’ve batted extremely well, and years where I’ve driven in a lot of runs, but I don’t think I’ve had a year yet where I’ve combined all that.”39

However, the career year didn’t materialize that season. Instead, the opposite happened. With Kevin Mitchell gone and third baseman Matt Williams having a poor season, Clark’s slugging numbers were down because he was frequently being pitched around.

The months of August and September were brutal for the Giants, as they won only 20 of 56 games. They ultimately dropped to fifth place, 26 games behind the division-leading Atlanta Braves. Clark finished the season with 16 HR and 73 RBIs, his lowest since his rookie season. However, he did manage to bat .300 and record 40 doubles, a career high at that point. If there was any consolation for the season, he was selected as the Giants’ sole representative on the National League All-Star team, for whom he hit a three-run home run in the eighth inning.

Giants owner Bob Lurie wanted to sell the team to a group in Tampa-St. Petersburg, after not gaining approval to build a new stadium in San Jose. However, he wound up selling the team to Safeway chairman Peter Magowan after the National League owners rejected his proposal to sell to the Florida group. Magowan kept the team in San Francisco, and his first major change was the signing of free-agent Barry Bonds to a $43.75 million contract in late December 1992.40

As soon as Bonds’s contract signing was announced by the Giants, rumors started to circulate that Clark would be upset by the money being paid to Bonds and the “savior” label Bonds was being tagged with by the media. However, according to the San Francisco Chronicle, Bonds reached out to Clark first to make a goodwill gesture to try to head off any ill feelings.41 After having several conversations with Bonds over the winter, Clark reported, “We’re going to get along fine. I have a good relationship with Barry. That shouldn’t alter as long as we go out and do the job. I have no problem with Barry. He’s an MVP. He’s done it all. It’ll be like when Kevin Mitchell was batting behind me.”42

Bonds started the 1993 season as advertised, while Clark was having the worst April of his career, hitting below .200 with only one home run. However, the Giants were winning.

At one point during the season, Clark had 181 plate appearances (April 11 to May 28) without a home run. He denied to the press that he was in a slump, but acknowledged he wasn’t helping the batters behind him in the batting order. Preliminary discussions about his contract, which was scheduled to end after the 1993 season, didn’t produce any results. By the end of May his agent halted any more negotiations for fear of distracting Clark on the field.43

Over the next three months, due to a rash of injuries Clark was in and out of the linuep, including his first time since his rookie season on the disabled list, for two weeks on August 25. Bonds, Williams, and Robby Thompson were carrying the team as they led the NL West Division for most of the season.

By the time Clark got back into the lineup in mid-September, the Giants had lost eight straight and fallen to second place behind Atlanta. The Giants wound up being tied with the Braves on the last day of the season, each having won 103 games. San Francisco lost a heart-breaker to the Los Angeles Dodgers while the Braves defeated the Colorado Rockies to claim the West Division title.

When Bonds had come on board with the Giants, he revealed two of his goals with the Giants were to win two more MVP Awards and go to a World Series. He made progress toward those aspirations in 1993 by being the overwhelming winner of the National League MVP Award and narrowly missing out on the playoffs. Having his second consecutive subpar season (.283 BA, 14 HR, and 73 RBIs) and missing 30 games mostly due to injuries, Clark was pushed to the back of the Giants’ stage.

Clark’s contract negotiation with the Giants picked up again after the season. In deciding whether to retain Clark, the Giants needed to figure out whether his last two seasons were an aberration or a trend. Second baseman Robby Thompson’s contract was also due for renewal, and there was some speculation the Giants wouldn’t be able to afford both players going forward. Making their decision even harder, Thompson had just come off the best season of his career with Gold Glove and Silver Slugger awards in his trophy case, while Clark’s performance was declining.

Clark’s agent, Jeff Moorad, commented in The Sporting News immediately after the 1993 season, “We’re ready to sign today. The Giants are the only organization Will has known. He would like nothing better than to retire in a Giants uniform.”44 Clark echoed the same sentiments in mid-October, “I think people have the idea I’m gone, that I’m out of here as a free agent, and that’s just not the case. I’ve watched guys like George Brett and Mike Schmidt spend their entire career with one team, and I’m a firm believer in that.”45

Clark formally filed for free agency, even though Moorad indicated they were still hopeful of being able to work out a deal with the Giants. USA Today Baseball Weekly reported the Orioles, Mets, and White Sox were expected to pursue Clark, and the Rangers and Rockies would also likely enter the chase if they couldn’t re-sign their incumbent first basemen, Rafael Palmeiro and Andres Galarraga.46

When Rafael Palmeiro dismissed initial discussions with the Rangers about a five-year $26 million deal and decided to enter the free agent market, the Rangers initiated deliberations with Clark, who was disappointed with the Giants’ offer of a three-year deal at less than $15 million. Palmeiro was peeved at the Rangers for talking to his former Mississippi State teammate, since he felt like he was the better player.

Unable to reach a long-term deal with the Giants, Clark ultimately signed a five-year contract with the Rangers worth $30 million. Palmeiro was stunned upon learning Clark had inked the contract, since he had been essentially looking for the same deal with the Rangers. He was bitter at the Rangers for never putting an official offer on the table. Furthermore, in his frustration, he had harsh words for Clark, whom he believed had gone to the Rangers behind his back.47

Clark responded, “When free agency comes along, you can’t always stay with the same team. I had to come to grips with that in San Francisco. That’s the one thing I wanted. I’d have loved to be with the Giants all my days. But it didn’t come down to that. The Rangers have made me a part of their family. I’m honored.”48

Palmeiro, who signed with Baltimore, would harbor ill feelings for Clark that lasted until 2015. It was during the filming of a documentary by ESPN Films (SEC Storied – Thunder and Lightning) featuring the two former teammates) that they finally made up and started speaking to each other again.

Rangers manager Kevin Kennedy welcomed Clark’s leadership in the clubhouse in 1994. Clark made a good impression with the team from the get-go. He started out with a hot bat in April and was having a positive effect on the other players in the lineup. Rangers hitting coach Willie Upshaw observed, “Clark elevated the Rangers’ offense by example, showing his teammates exactly what situational hitting is all about. The other guys have seen him stay within himself game in and game out.”49

At the All-Star break, Clark was putting up his best season since 1989 (.353/.449/.571, 13 HR and 78 RBIs) and was rewarded with his sixth All-Star Game selection. He appeared to be on his way to that “career year.” Then, bothered by a sore right knee, Clark’s performance took a sharp decline after the break. He was no longer getting on base at the same rate as before, and his power was practically non-existent.

Then an even worse thing happened. On August 12, major-league baseball owners locked out the players over their disapproval of a salary cap the owners wanted to institute as part of a new revenue-sharing plan. Even though the Rangers had a losing record, they led their division at the time of the shutdown, which abruptly ended the regular season. Moreover, there would be no postseason playoffs and World Series.

The 1995 regular season didn’t start until April 26, following a federal judge’s issuance of an injunction against the owners from locking out the players. Clark fractured his left elbow in the third game of the season, but decided to play through the injury. He missed 21 games during the season and finished with a slash line of .302/.389/.480, 16 HR, and 92 RBIs.

Clark’s power numbers dropped significantly with the Rangers as he continued to struggle with injuries. He often played through his health problems, which earned him the respect of his manager and teammates. After two subpar years, he rebounded in 1998, hitting .304 with 23 HR and 102 RBIs, as the Rangers won the AL West Division for the second time in three years.

Clark’s power numbers dropped significantly with the Rangers as he continued to struggle with injuries. He often played through his health problems, which earned him the respect of his manager and teammates. After two subpar years, he rebounded in 1998, hitting .304 with 23 HR and 102 RBIs, as the Rangers won the AL West Division for the second time in three years.

Despite that, Clark was released after the 1998 season (the Rangers signed free agent Rafael Palmeiro to replace him) and signed with the Baltimore Orioles. He missed half the 1999 season with injuries, and part of 2000 before he was traded to the St. Louis Cardinals in July 2000, to fill in for the disabled Mark McGwire.

During the last two months of the season for the Cardinals, the 36-year-old Clark hit like he had in his early days as a Giant, collecting 12 HR and 42 RBIs and posting a .345 batting average and .426 on-base percentage.

The Cardinals swept the Atlanta Braves in the Division Series, with Clark hitting a dramatic three-run home run off Tom Glavine in Game Two. They advanced to play the New York Mets in the League Championship Series, but were defeated in five games. Clark led the Cardinals with a .412 average while hitting another home run.

The Sporting News reported the Cardinals were interested in re-signing Clark for 2001 as an insurance policy at first base, but he would have to agree to less money and less playing time behind Mark McGwire who was expected to return as the starter at first base.50

However, in early November Clark announced that he was retiring after a 15-year career. He told reporters in St. Louis, “In every player’s career, sooner or later, you’re going to have to make a decision to move on. I can still hit, I can still play, still field my position. But also, at the same time, it’s the right time for me to exit.” He didn’t rule out the possibility of serving the St. Louis organization later in some capacity.51

Yet, it was a bit surprising when Clark retired immediately after the 2000 season. He had just come off one of the best two-month stints of his career, and at 36 it would seem he had a couple more seasons in him.

But it wasn’t about his ability to continue to play that led to his decision. He and his wife, the former Lisa Ann White, had two small children, Ella and William III (Trey), a two-year-old who had been diagnosed with Pervasive Development Disorder, a form of autism. Clark felt he needed to focus his attention on helping Lisa care for Trey. The time away from the family during spring training and the regular-season road trips prevented Clark from providing the kind of stability he and Lisa wanted for their son. Years later, Clark would be a volunteer coach for Trey’s baseball team at a private high school near Baton Rouge.52

Clark served as an advisor to the Arizona Diamondbacks’ coaching staff in spring training 2004-2008 and as a community ambassador for the San Francisco Giants from 2009 to 2015.

Will Clark might “lead the league” in number and variety of post-career honors he’s accumulated. He has been inducted into the Diamond Club of New Orleans Hall of Fame (2001), Louisiana Sports Hall of Fame (2003), the Sugar Bowl Hall of Fame (2003), the New Orleans Professional Hall of Fame (2007), and the Louisiana High School Athletic Association Hall of Fame (2012).

In Mississippi, where he was an All-American at Mississippi State University, he holds a place of honor in the Mississippi State University Hall of Fame (2003) and Mississippi Sports Hall of Fame (2008).

He was inducted into the inaugural class of the College Baseball Hall of Fame (2006) and was named to the College World Series Legends Team (2010) in a poll of college baseball writers and Division I coaches.

The Bay Area Sports Hall of Fame in California inducted him in 2007. The San Francisco Giants honored Clark with a bronze plaque on their Wall of Fame in the inaugural class in 2008. His jersey number 22 was retired by the Giants in 2022, one of only 13 in franchise history at the time of this writing.53

However, the ultimate honor for a major-league player is election to the National Baseball Hall of Fame, which has eluded Clark despite his brilliant career. In his first year of eligibility in 2006, he received only 4.4% of the votes of the Baseball Writers Association of America. Since a minimum of 5% is required in the first year, he fell off the voting ballot for future consideration.

Then he got a second chance in 2017 when he was one of ten former players (whose primary contributions occurred after 1988) nominated for Hall of Fame induction. In order to be enshrined, nominees must receive 75 percent of the votes by a panel of 16 experts, known as Today’s Game Era Committee. At the time of his nomination, Clark said, “That would be a big-time feather in the cap if that happens. But if it doesn’t, that’s OK. Because I didn’t play this sport to get into the Hall of Fame. I played this sport because of the challenge and competition.”54

Clark’s career slash line of .303/.384/.497 compares favorably with many current Hall inductees. His 28.2 WAR (Wins Above Replacement) in his prime years (1987-1991) rank him first among all Major League first basemen and sixth behind Barry Bonds, Wade Boggs, Cal Ripken Jr., Rickey Henderson, and Ozzie Smith. Clark led all big-leaguers in those five years with a 153 OPS+ (On-Base Plus Slugging Percentage adjusted for ballpark factors). He was named to the MLB All-Star team in five of his first seven seasons. In four of the seasons between 1987 and 1991, he was among the top five vote-getters for National League MVP.

Clark concluded his career with 284 HR and 1,205 RBIs in 1,976 major-league games. He scored 1,186 runs and collected 2,176 hits. One wonders what Clark’s career numbers would have been had he not suffered many injuries and played a few more seasons.

But Clark didn’t receive the required number of votes for election by the Committee, probably because his years of peak performance were too short when compared to other nominees. Had he performed at a similar level for another five seasons or so, he could very well have his bronze plaque in Cooperstown.

Nevertheless, Will “The Thrill” remains an icon of the game from his era. His intensity, his menacing scowl, and his sweet swing have forever earned him a place in the hearts of baseball fans who saw him play. And specifically in his hometown of New Orleans, Clark shares the highest pedestal with the city’s other diamond legends, Mel Ott and Rusty Staub.

Last revised: August 28, 2024

Acknowledgements

This biography was reviewed by Norman Macht and fact-checked by Alan Cohen. It is a condensed version of the author’s nine-part series “Will Clark: Oh, What a Thrill!” on CrescentCitySports.com in March and April 2018.

Sources

In addition to the notes below, the author consulted the following sources.

1993 San Francisco Giants Information Guide: 69-72.

1998 Texas Rangers Media Guide: 39-44.

2000 Baltimore Orioles Information & Record Book: 65-69.

Alexander, Jim, “Reflections: U. S. may have proven best in longer series,” Baseball America, September 1, 1984: 29.

Atkinson, Paul. “N.O.’s Will Clark is trying to move into Ott’s league,” Times-Picayune, July 29, 1990: 1F1.

Baseball-Reference.com.

Firmite, Ron. “The Bay Area Bombers,” Sports Illustrated, April 4, 1988: 44-49.

Lagarde, Dave. “Clark following in Staub’s footsteps as career begins,” Times-Picayune, April 8, 1986: B2.

Peters, Nick. “Clark and Mitchell: Most Valuable Pair,” Giants Magazine (Vol 4, No. 1): 16-24.

Ratto, Ray. “The Thrill of It All,” SPORT, July 1990: 24-28.

Winkworth, Bruce. “Mississippi State’s Power Package,” Baseball America, February 12, 1985: 3.

Notes

1 Peter Finney, “All-Star Game rings home to Clark,” Times-Picayune, July 11, 1989: E1.

2 Finney.

3 “Deaths: William Nuschler Sr.,” Times Picayune, September 15, 2001: Metro Section, 1.

4 Peter Finney, “What can Clark do for an encore?” Times-Picayune, October 14, 1989: D1.

5 Frank Donze, “Baseball’s ‘Thrill’ born with will,” Times-Picayune, October 14, 1989: A1.

6 Jim Reeves, “Baby Boomers: They’re Young, Strong, and Filled With Springtime’s Promise,” The Sporting News, April 21, 1986: 10.

7 Rob Rains, “Superstar driven by a Will to win,” USA Today Baseball Weekly, May 20-26, 1992: 36.

8 Nick Cafardo, Jim Callis, Paul Hagen, John Hickey, Ken Leiker, John Perrotto, Ken Rosenthal, Mark Ruda, Bill Shaikin, John Sheu, and Bob Sherwin, “Players Discuss Olympics,” Baseball America, November 10, 1991: 3.

9 “Will Clark hits homer, double in Giants exhibition opener,” Times-Picayune, March 8, 1986: B6.

10 Reeves.

11 “Clark will start for Giants,” Times-Picayune, March 24, 1986: B5.

12 Dave Lagarde, “Clark homers in first time at bat for Giants,” Times-Picayune, April 9, 1986: C1.

13 “E.M. Swift, “Will Power,” Sports Illustrated, May 28, 1990: 74.

14 Stan Isles, “Giants’ Clark Will Not Make Comparisons,” The Sporting News, April 11, 1988: 6.

15 “E. M. Swift, “Will Power,” Sports Illustrated, May 28, 1990: 76.

16 Peter Barrouquere, “Will Clark earning Giants’ respect,” Times-Picayune, March 20, 1986: B1.

17 Nick Peters, “’Frisco’s Baby Boomers,” The Sporting News, September 27, 1987: 12.

18 “Giants win, but Clark injured,” Times-Picayune, June 4, 1986: C4.

19 Peter Barrouquere, “Clark enjoying banner season for Giants,” Times-Picayune, August 14, 1987: D1.

20 Glenn Dickey, “It’s Not Easy Being God,” SPORT, April 1988, 63.

21 Tom Weir, “For Clark, the hit was a sure thing,” USA Today, October 10, 1989.

22 Glenn Dickey, “It’s Not Easy Being God,” SPORT, April 1988: 63.

23 Nick Peters, “S. F. Giants Team Review,” The Sporting News 1988 Baseball Special: 30.

24 Tim Cowlishaw, “Respect means walks, votes for Giants’ Clark,” Times-Picayune, July 12, 1988: E1.

25 Nick Peters, “’Frisco’s Baby Boomers,” The Sporting News, September 27, 1987: 12.

26 Glenn Dickey, “It’s Not Easy Being God,” SPORT, April 1988: 63.

27 Nick Peters, “Clark Stars in an Early Hit Show,” The Sporting News, May 8, 1989: 18.

28 Nick Peters, “Will Clark: More Than a Slugger,” The Sporting News, June 5, 1989: 17.

29 “Will Clark: More Than a Slugger.”

30 Jerome Holtzman, “Giant Effort Clubs Cubs,” Chicago Tribune, October 5, 1989: Section 4, Page 1.

31 Paul Attner, “Series Diminishes In Wake of Quake,” The Sporting News, October 30, 1989: 11.

32 Peter Barrouquere, “Giants give Clark $15 million contract,” Times-Picayune, January 23, 1990: E1.

33 Nick Peters, “Bottom Line on Clark Contract: $25,000 a Hit!” The Sporting News, February 25, 1990: 32.

34 Art Spander, “Phi Betamax Kappa of Hitting Can’t Pass Test,” The Sporting News, September 17, 1990: 59.

35 “Clark: Foot Injury a Problem All Season,” The Sporting News, October 1, 1990: 18.

36 Peter Barrouquere, “Clark leaves his pain behind,” Times-Picayune, March 13, 1991: D1.

37 Mark Newman, “Baseball ’91: Will Clark,” The Sporting News, April 1, 1991, S-25.

38 Mark Newman, “San Francisco Giants Team Review,” The Sporting News, August 26, 1991: 19.

39 Rob Rains, “Superstar driven by a Will to win,” USA Today Baseball Weekly, May 20-26, 1992: 36.

40 Susan Fornoff, “New and Improved,” The Sporting News, June 28, 1993: 9.

41 Scott Ostler, “S. F. big enough for Clark, Bonds,” Times-Picayune, January 24, 1992: C3.

42 “Clark is set to play with Bonds,” Times-Picayune, February 24, 1993: C3.

43 Larry Stone, “San Francisco Giants Team Review,” The Sporting News, June 7, 1993: 26.

44 Larry Stone, “San Francisco Giants Team Review,” The Sporting News, October 18, 1993: 26.

45 Larry Stone, “San Francisco Giants Team Review,” The Sporting News, October 25, 1993: 23.

46 Larry Stone, “San Francisco Giants Team Review,” The Sporting News, November 1, 1993: 24.

47 “Clark sidesteps Palmeiro’s verbal jab,” Clarion-Ledger, November 24, 1993: 1C.

48 Mel Antonen, “Clark sidesteps blasts from former teammate,” USA Today Baseball Weekly, November 24, 1993: 3C.

49 T. R. Sullivan, “Texas Rangers Team Review,” The Sporting News, May 23, 1994: 32.

50 Rick Hummel, “St. Louis Cardinals Team Review,” The Sporting News, November 6, 2000: 29.

51 Jimmy Smith, “Clark suddenly calls it quits after 15 years,” Times-Picayune, November 3, 2000: 1 (Sports Section).

52 Lloyd Courtney, “Where are they now: Will Clark focuses on family,” Shreveport Times, May 17, 2015. https://www.shreveporttimes.com/story/sports/2015/05/17/now-will-clark-focuses-family/27503883/. Retrieved August 22, 2018.

53 Evan Webeck, “Emotional Will Clark Has No. 22 Retired By SF Giants: ‘This Is My Hall Of Fame,’” East Bay Times (Walnut Creek, California), July 30, 2022. https://www.eastbaytimes.com/2022/07/30/emotional-will-clark-has-no-22-retired-by-sf-giants-this-is-my-hall-of-fame/. Accessed July 2, 2024.

54 Chris Haft, “Will in-depth numbers support Clark’s cause?” MLB News, November 29, 2016. https://www.mlb.com/news/will-clark-considered-in-hall-of-fame-vote/c-209864780. Retrieved August 22, 2018.

Full Name

William Nuschler Clark

Born

March 13, 1964 at New Orleans, LA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.