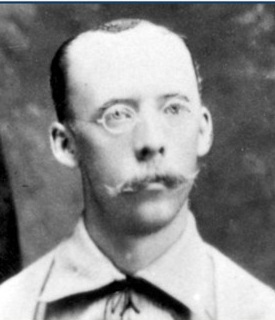

Will White

He is the answer to one trivia question and half of the answer to another, but there was nothing trivial about the life of Will White.

He is the answer to one trivia question and half of the answer to another, but there was nothing trivial about the life of Will White.

William Henry White was born in Caton, a farming community in Steuben County, in western New York, just a few miles above the Pennsylvania state line. He was the fourth of the eight children of Adeline and Lester White, a farmer. While still a child, Will started playing baseball with his family. His older brother James and a cousin, Elmer White, were among the earliest professionals, playing in the National Association — considered by some the first major league — as early as 1871, its first year of existence. (In 2010 James, known as Deacon White, was selected by the Society for American Baseball Research as the Overlooked Nineteenth Century Baseball Legend of the year. Overlooked no longer, he was named to the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 2013.)

Will never became quite as famous as his older brother, but his accomplishments in his short career were as impressive as those of several Hall of Fame pitchers. He has been compared to Addie Joss, Dizzy Dean and Sandy Koufax, all of whom are in Cooperstown.1 He won more major league games than any of that immortal trio and had a better earned run average than either Dean or Koufax.

By 1875 Will White had developed a sharp-breaking curveball and was pitching for the Lynn (Massachusetts) Live Oaks, one of the strongest amateur clubs in the country. In a tournament in Watertown, New York, White met Harry McCormick of the Syracuse Stars and taught his future teammate how to throw the curveball.2 In 1875 or 1876 White married teenaged Harriet Holmes. Their daughter Katherine was born in December 1876. In 1876 White pitched for the Binghamton Crickets, a year before the Crickets became all professional — meaning they paid all their players — and joined the League Alliance, a 28-team minor-league circuit for which 1877 was its only season.

White went on to bigger and better things. His brother Deacon convinced the Boston Red Stockings (or Red Caps, as they were sometimes called) to give Will a three-game tryout. The 5-foot-9, 175-pound right-hander made his major league debut at age 22 on July 20, 1877, losing to the Cincinnati Reds, 13-11. However, he pitched much better than the score indicates. His teammates let him down, committing error after error and allowing enough unearned runs to cost him a victory. In his three games, he pitched a complete game every time, won two, and lost one, threw one shutout, gave up 27 hits, walked two, and struck out seven. He allowed 15 runs, only 9 of which were earned, for an ERA of 3.00. He proved he could pitch well in the major leagues.

During those three games White accomplished two things to the delight of trivia fans. Will became the first major leaguer ever to play baseball while wearing eyeglasses on the field. A ballplayer wearing glasses attracted a great deal of attention and was a rarity for many years. An article in The Sporting Life stated, “White was about the only pitcher of consequence who wore glasses. He had great control of the ball, and he could land one over the plate whenever he wanted to notwithstanding he was handicapped by weak eyes.”3 A newspaper article in 1911 stated that there were no players wearing eyeglasses at that time and there had been none since White. The piece quoted Hall of Fame slugger Dan Brouthers as saying, “Will White was, I suppose, the last of the eye-glassed professionals. Near-sighted as Roosevelt — and Teddy could play a good game of ball, I’ll bet — White was nevertheless a great pitcher. He had the curves, the speed and all sorts of scientific trickery.”4

With Will pitching and Deacon catching, the Whites became the first brother battery in major league history, thus answering another trivia question. The brothers both left Boston and joined the Cincinnati Reds in 1878. With the reserve clause not yet in effect, players were free at that time to sell their services to the highest bidder. The Reds got their money’s worth with the Whites. Deacon was at the height of his Hall of Fame career. Will was phenomenal. In 1878 he pitched 52 complete games in 52 starts, won 30 games and posted a 1.79 earned run average. In July he earned the nickname “Whoop-La,” for his victory shouts after wins.

In 1879 Will was even better, putting up numbers that seem incredible to modern fans. He started 75 games and completed every one of them, pitching 680 innings. He won 43 games, lost 31, had an ERA of 1.99, and struck out 232 batters. He set several records that have remained unbroken to the present day, including most starts, most complete games and most innings pitched.5

During the 1879 season White demonstrated his curveball. Three posts were set up in a line. O.P. Caylor, a Cincinnati sportswriter and future baseball executive, described the demonstration: “White stood upon the left of the fence at one end so that his hand could not possibly pass beyond the straight line, and pitched the ball so that it passed to the right of the middle post. This it did by three or four inches, but curved so much that it passed the third post a half foot to the left.”6

In 1880 White again finished everything he started, throwing 62 complete games in 62 starts. He compiled a sparkling 2.14 earned run average, but his weak-hitting Cincinnati teammates gave him little support. The Reds hit .224 as a team and scored only 296 runs in 83 games in a season when the average number of runs scored per team was nearly 400. White’s won-lost record was an abysmal 18-42.

Not surprisingly, Cincinnati fans did not fill the stands to root for a losing team. In order to make ends meet, the club’s owners started selling beer on the grounds and renting the park to local amateur and semipro clubs for Sunday games. William Hulbert, president of the National League, ordered the Reds to cease both practices. When the Reds refused to agree to Hulbert’s edict, the National League expelled the Cincinnati club. Will White was suddenly without an employer.

In 1881 the Detroit Wolverines joined the National League, and White signed with them. He pitched two games for his new club in May, losing both. He may have been suffering from a sore arm.7 At any rate, Detroit released him after the two losses. White returned to Cincinnati and spent the summer pitching for local semipro teams.

A new major league, the American Association, started play in 1882. Dubbed the Beer and Whiskey League because it permitted the sale of alcoholic beverages in its parks, it welcomed Cincinnati into its membership.

Before the season started the Cincinnati club, called the Red Stockings or the Reds, signed Will White as its lead pitcher and raided the National League to fill out the roster. Only the rookie second baseman, Bid McPhee, lacked National League experience. Ironically, he turned out to be best of the lot, the only member of the 1882 Reds to reach Cooperstown.

Cincinnati dominated the league in its inaugural season, winning the pennant by a margin of 11½ games. White was the league’s best pitcher, with a record of 40-12, a .769 winning percentage, and an ERA of 1.54. He led the league in wins, percentage, complete games, shutouts, and innings pitched. Pete Palmer and Gary Gillette honored him with the first of two consecutive Ex Post Facto Cy Young Awards.8

By 1882 the formerly error-prone fielder had improved to the point where he was one of the better-fielding pitchers in the league. The man who had made an incredible 76 in errors in 62 games for Binghamton in 1876 reduced his miscues to 11 in 1882. More importantly, he set a major league record for assists by a pitcher by throwing out 223 opponents. That number was exceeded by Ed Walsh 25 years later, but it remains the second-highest total in major-league history.9

One of White’s eight shutouts in 1882 came in the famous game of July 21, when he defeated Pittsburgh, 2-0, in a game that was delayed while the Red Stockings’ Chick Fulmer feigned illness to enable Hick Carpenter to reach the ballpark in time to play in the game. A more important shutout came in a postseason exhibition game against the three-time NL champion Chicago White Stockings. Although it was just an exhibition, not the start of the World Series, the contest had great symbolic importance. It proved that the champions of the new American Association could compete on even terms with the champions of the established National League. White hurled a masterpiece, defeating the haughty National Leaguers, 4-0. He pitched the second game in the series and lost it, but the American Association had proven its legitimacy in the first contest, thanks to White’s pitching.

White proved that his 1882 season was not a fluke by winning a league-leading 43 games in 1883 and leading the circuit in earned run average with 2.09. Naturally, he was Cincinnati’s pitcher of choice for the Opening Day 1884 game against the St. Louis Browns. In his book on the American Association, The Summer of Beer and Whiskey, Edward Achorn described the scene at the Bank Street Grounds: “Under a brilliant blue sky the baseball lovers looked out over the packed wooden stands and a well-groomed diamond, with thirty-six carriages and buggies and two ladies on horseback parked deep in the green outfield.”10 A large pennant, with big blue letters “Champions 1883,” was raised on a flagpole north of the bleachers. White had awakened that morning with a sore shoulder, but he said he would try to pitch anyway.

The game was a thriller, a real nail-biter. Cincinnati jumped off to a 4-0 lead in the first inning. St. Louis pitcher Jumbo McGinnis held the Reds scoreless for the next ten innings. Cincinnati captain Pop Snyder complained that McGinnis was throwing on a level with his head, in violation of the pitching rules of the era, which prohibited raising the arm above shoulder level. Snyder’s protests were of no avail.

Meanwhile, White, even with his sore shoulder, shut down St. Louis until the eighth inning, when the Browns rallied to tie the score, 4-4. Neither club scored in the ninth or the tenth. In the top of the eleventh St. Louis took a 5-4 lead. In the Cincinnati half of the frame, Joe Sommer led off with a single and scored on a double by Pop Corkhill, tying the score, 5-5. Snyder grounded out, but Chick Fulmer smashed a hard grounder into left field, plating Corkhill and winning the game for White and the Reds, 6-5.

A deeply religious man who refused to pitch on Sundays, White was baptized in the Second Advent denomination, which today claims about 25,000 adherents, by being immersed in the Ohio River, near Dayton, Kentucky, in August 1883.

Will White was not a typical ballplayer for his era. In a time when many ballplayers were heavy drinkers, who sometimes showed up with hangovers after a night on the town, White did not waste his money on women and drink. Instead he invested not in a saloon, but in a tea shop on Market Street in downtown Cincinnati, where he worked behind the counter in the offseason. Not a typical ballplayer, perhaps, but a fierce competitor, certainly. Achorn wrote that White did not look like a fearsome competitor, but “came across as a timid, rather professorial man, with his wire-rimmed spectacles, premature baldness, and formerly blond hair which had turned white when he was just twenty-eight.” 11

White’s competitive nature may be illustrated by his penchant for pitching inside to intimidate batters. In 1884, the first season for which records are available, White led the majors with 35 hit batsmen. Prior to that he had undoubtedly hit many more batters in a season. Before 1884, batters hit by a pitch were not automatically entitled to first base. According to baseball historian David Nemec, the rule change deprived White of one of his chief weapons, intimidation.12 White had started the 1884 season as the player-manager of the Reds, who compiled a 44-27 record under his guidance. Despite this success, he decided to step down as manager in August, turning the reins over to Pop Snyder. He explained that he was of “too easy a disposition.”13

In 1884 White won 34 games while losing 18. It was his last season with 30-plus wins. In 1885 his record was 18-15, but he still completed 33 of his 34 starts. According to Overfield, after the 1885 season White’s arm had nothing left.14 In the offseason he opened a grocery store in Fairmount, Ohio, near Cincinnati He pitched a few games in 1886, winning one and losing two. On July 5, at age 31, his major league career was over.

After his playing days were over, White studied opthalmics in Corning, New York. In 1889 he and his older brother, Deacon, entered into two enterprises together. They went into the optical supply business as the Buffalo Optical Company and at the same time were associated with the Buffalo Bisons, a baseball club in the International League. Deacon and Jack Rowe had purchased the Bisons, intending to be co-owners, managers and players. Will agreed to pitch for the Bisons and serve as an assistant manager. However, these plans fell through. The National League had instituted the reserve clause in stages from 1879 to 1884. The Pittsburgh Alleghenys owned the rights to Deacon White and Rowe and refused to release them, so the duo had to return to Pittsburgh, leaving Will White in charge of the Buffalo club. He pitched 20 games for the Bisons, with a record of 7-13 and 2.33. That ended his involvement in baseball.

Back in Buffalo, White worked as an optician for over a decade. His Buffalo Optical Company in downtown Buffalo was successful. He was founder and chief benefactor of the Christ Mission in Buffalo, a center he established to meet the spiritual and practical needs of the poor, providing not only food and shelter but also by demonstrating Christian love. Things were going well for Will White until tragedy struck. On August 31, 1911, White was teaching his niece to swim at his summer home in Port Carling, Ontario. He suffered a heart attack while in the water and drowned. He was 56 years old. In his will he left 10 percent of his $21,000 estate to Christ Mission, and directed his daughter Katherine (aka Mrs. Franklin Moore Shull) to do the same with her share.

William Henry White was buried in Forest Lawn Cemetery in Buffalo. It might be said that he was a great pitcher and an even better man.

Sources

Notes

1 Joseph M. Overfield, “William Henry White,” in Robert L. Tiemann and Mark Rucker, eds., Nineteenth Century Stars. Kansas City; Society for American Baseball Research, 1989, 137.

2 Lloyd Johnson, “Patrick Henry McCormick (Harry),” in Frederick Ivor-Campbell, Robert L. Tiemann, and Mark Rucker, eds., Baseball’s First Stars, Cleveland: Society for American Baseball Research, 1996, 103.

3 The Sporting Life, February 3, 1900.

4 Bemidji Daily Pioneer, July 12, 1911.

5 Lyle Spatz, ed. The SABR Baseball List and Record Book, New York: Scribner, 2007, 228, 231, 232.

6 O.P. Caylor, “The Theory and Introduction of Curve Pitching,” http://library.la84.org.

7 Overfield, op. cit.

8 Pete Palmer and Gary Gillette, eds. The Baseball Encyclopedia, New York: Barnes and Noble, 2004/ 1667.

9 Spatz, op. cit., 326.

10 Edward Achorn, The Summer of Beer and Whiskey, New York: Public Affairs, 2013, 84

11 Ibid., 117.

12 David Nemec, The Great Encyclopedia of Nineteenth Century Baseball, Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2006, 121.

13 Lee Allen, The Cincinnati Reds, Kent, Ohio: Kent University Press, 1948, 31.

14 Overfield, Op. cit.

Full Name

William Henry White

Born

October 11, 1854 at Caton, NY (USA)

Died

August 31, 1911 at Port Carling, ON (CAN)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.