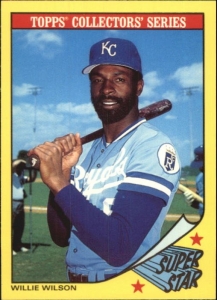

Willie Wilson

“I always hope he hits the ball to left so I can watch him run, because I’ve never seen anything like him turning second.” — Dwight Evans of the Red Sox, talking about Willie Wilson in 19801

“Having Willie Wilson in center field is like having four outfielders.” — Billy Scripture (Wilson’s first minor-league manager) in 19742

Willie Wilson did not know his father.

Willie Wilson did not know his father.

Willie James Wilson was born in Montgomery, Alabama, on July 9, 1955 and as a young boy lived with his grandmother, Annie Mae (known as Madear). Uncle Tim, Aunt Sally, and his great-grandmother. His other aunts and uncles lived nearby and included Aunt Martha, who taught him life’s early lessons. They all lived in the Jackson Heights section of Montgomery, and Willie’s first schooling was at the segregated George Washington Carver Elementary School. He was there through the first grade, when he went to live with his mother in Summit, New Jersey. He was escorted on the long bus trip by his grandmother and his uncle Tim. After moving north, he would return to the South during the summers and work on the family farm.

At the end of the long bus trip from Montgomery to Newark, New Jersey, Willie met his mother, Dorothy, for the first time. By then, she was Dorothy Lynn, having married Gene Lynn and had a baby, Willie’s younger brother, Anthony. George earned a living in Summit, New Jersey, where they settled, washing windows, but Willie’s mother and stepfather divorced while Willie was in elementary school.

New Jersey was a new experience for young Willie, who was enrolled at Lincoln Elementary School. The school was predominantly white, with only a handful of black students. He played youth football in the Pop Warner League and by the time he got to high school, the athletic youngster was ready to excel. His football coach, Howie Anderson, and baseball coach, Dominic Guida, guided him through four formative years, and Art Cottrell coached him in baseball at Summit High School.

Although the picture of a fleet-footed Willie Wilson manning the outfield is familiar to most fans, he was a catcher during his high-school years. His hero among major-league players of the time was catcher Manny Sanguillen of the Pittsburgh Pirates. His other hero was running back Gale Sayers of the NFL Chicago Bears. Knowing of how Willie felt about Sayers, coach Anderson arranged to have Sayers visit Wilson in the hospital when Willie was recovering from a football injury. Part of championship teams in both baseball and football, Willie had thoughts of going to the University of Maryland on an athletic scholarship.

But after signing a letter of intent to go to Maryland, Wilson was drafted in the first round by the Kansas City Royals in the June 1974 draft. Accompanied by his mother, football coach Anderson, and lawyer Gil Owren, Wilson went to Kansas City and signed with the Royals for $90,000, some of which went to pay bills that his mother, a single woman who had lost her job, had accrued.

Wilson’s first stop as a professional ballplayer was Sarasota in the Gulf Coast League. Rookie League was a time of adjustment for him. Not only was he away from home for the first time, but he was learning to play the outfield and facing hard throwers, some with not much control, in every game. After a slow start, he finished well to raise his batting average to .252. He stole 24 bases in 47 games.

In 1975 Wilson was at Waterloo in the Class-A Midwest League. His team ran away with the divisional title, posting a 93-35 record. He led the league in hits (132), set a Midwest League record with 76 stolen bases, and was named the league’s player of the year. The next season, he was at Jacksonville in the Double-A Southern League. In early August, the Royals scouting director and director of player development, John Schuerholz, said, “We believe he is playing center field as good or better than anybody in the organization. Defensively, Willie is a major-league center fielder right now.”3 After 107 games, Wilson was batting .253 with 37 stolen bases when he was sidelined with a hamstring injury. When he came off the DL on September 2, he was called up to the Royals and made his major-league debut against the Texas Rangers on September 4, entering the game in Kansas City as a defensive replacement for Amos Otis in the ninth inning.

Wilson’s next appearance, on September 9, was a harbinger of his basepath wizardry at the big-league level. In the bottom of the ninth inning at home against the Angels, with the Royals trailing 5-3, John Mayberry singled in Tom Poquette and advanced Fred Patek to third base. Wilson was inserted as a pinch-runner for Mayberry. Pitcher Mike Overy tried to pick off Wilson and his throw eluded first baseman Tony Solaita. Patek raced home with the tying run and Wilson advanced to second. Willie had his first steal in a game the Royals would win in 10 innings.4

The next day, in a blowout at Minneapolis, Wilson had his first at-bats in the majors. The score was already 10-0 when he entered the game in the bottom of the fifth inning as a defensive replacement. By the time he came to bat in the seventh inning, the score was 17-0. With two out and a runner on first, Wilson hit a grounder between the shortstop and third base. By the time shortstop Roy Smalley fielded the ball, Wilson was approaching first base. Smalley held on to the ball and Wilson had his first-major league hit. That was his only hit in 12 at-bats in September 1976.

In spring training for the 1977 season, the decision was made to convert Wilson into a switch-hitter. As a right-handed hitter, he had had difficulty with the slider from right-handed pitchers. Hitting from the left side would counter the effectiveness of that pitch. Also, hitting from the left side would give him the opportunity to better utilize his speed going to first base. The season was spent at Triple-A Omaha. Wilson batted .281, his highest average in four minor-league seasons. At the end of the minor-league season he again was called up to the Royals, with much better results than 1976.

On September 15 at home against Oakland, he starred in a doubleheader sweep. In the first game, after entering the game in the ninth inning as a pinch-runner, he stayed in the contest, singling and scoring the winning run in the 11th inning. He made his first start in the second game and went 2-for-5 with a double, scoring the first two of his team’s runs in a 5-4 win. In 13 games, he batted .324. As a late season callup, Wilson was not eligible for the postseason and was a spectator as the Royals lost in the ALCS to the Yankees.

In the offseason between 1977 and 1978, Wilson played winter ball in the Dominican Republic and his hitting was aided when he worked with Licey Tigers teammate Manny Mota.

Wilson’s first full year in the majors was 1978, and he had his struggles adapting to big-league pitching. Although he played in 127 of his team’s games, starts were rare after May 23. He started 14 games in April and was batting .291 at month’s end. In May he went into a slump. After starting 15 games, during which he went 9-for-51 (.176), Wilson’s average after the doubleheader on May 23 stood at .236. Thereafter, most of his appearances were as a pinch-runner or defensive replacement. Although he stole 46 bases, his batting average for the season plummeted to .217.

The Royals won the AL West for the third consecutive year advanced to the ALCS, once again against the Yankees. Wilson first saw action in Games Two and Three as a pinch-runner. In Game Four, he started in left field and in the top of the fifth inning, with the score tied 1-1, beat out a grounder to shortstop for his first postseason hit. He advanced to second on a groundball but was gunned down trying to steal third base. The Yankees won the game, 2-1, and advanced to the World Series.

There was a degree of uncertainty going into the 1979 season, but an injury to Al Cowens on May 8 gave Wilson an opportunity to play regularly. After starting only six of his team’s first 30 games, he was given a start on May 11.

“It was a high fastball, and I just got on top of it. It went into the gap. It got through to the fence and I just kept running. When I got to third, they waved me in, and I just kept going.”

— Willie Wilson5

On May 13 manager Whitey Herzog put Wilson atop the batting order for the first time, and he went 3-for-6. In the top of the seventh inning, he faced Steve Trout of the White Sox. The game was already decided as the Royals were leading 10-3. With a runner on third and one out, Wilson hit the ball to left-center field and scampered around the bases for his first major-league home run. It was the first of his 13 career inside-the park homers.

He played in each of his team’s remaining games, all but two as a starter. A nine-game hitting streak from May 20 through May 29 pushed his average to .357. On a team based on speed, Wilson was the fastest and improved his base-stealing technique as he played alongside Amos Otis and Fred Patek.

During the season, Wilson and his wife, Kathy, had their first child, daughter Shanice Nicole. was born on August 29, after Wilson had been named AL Player of the Week for a six-game stretch during he went 13-for-24 (.542) and stole 8 bases.6 The couple’s second child, Donnel, was born on April 30, 1983.

The Royals won seven of eight games between August 22 and 30 and were briefly in first place. However, they were unable to capitalize on a good finish by Wilson (.336 with 18 stolen bases in September) and finished three games behind the Angels. For the season, Wilson stole a league-leading 83 bases and wound up batting .315. It was the first of four consecutive seasons in which his average was above .300. Although It was the only time he led the league in steals, it was the second of 15 consecutive seasons with 20 or more thefts.

In 1980 Wilson’s 705 at-bats not only led the American League, but also made him the first major leaguer with more than 700 at-bats. His league-leading 133 runs scored were the most runs ever scored in a season by a switch-hitter in the American League. His league-leading 230 hits tied the major-league record for hits by a switch-hitter in a season. He had 184 singles, the most ever by a player in the American League.7 He led the league with 15 triples, and his 79 steals were second in the league to Rickey Henderson’s 100. For Wilson, it would be the last time he stole more than 60 bases in the season. Factoring into his decision to run less often was the fact that if first base was open, intentional passes would be given to teammates like George Brett, who batted .390 that year. Wilson’s .326 batting average was overshadowed by Brett’s flirtation with .400. Wilson’s mastery of the outfield was recognized with his only career Gold Glove Award.

The Royals returned to the postseason in 1980. Once again, they faced the Yankees. In the second game of the ALCS, Wilson tripled in his team’s first two runs and scored the third Royals run as they took a 3-0 lead in the third inning. The Royals were clinging to a 3-2 lead when the Yankees threatened in the eighth inning. Willie Randolph was at first base with two outs when Bob Watson doubled down the left-field line. Wilson raced toward the corner, retrieved the ball and, as Randolph raced around the bases, threw the ball in. Brett relayed the throw to catcher Darrell Porter, who tagged out Randolph. The Royals won the game, took a 2-0 lead in the series, and traveled to New York to play in front of a crowd of 56,588 that included many of his hometown fans. New York took a 2-1 lead in the bottom of the sixth inning. Two Royals were retired in the top of the seventh inning when Wilson stepped to the plate against Tommy John. Wilson’s double ignited a rally topped off by Brett’s three-run homer that gave the Royals a 4-2 lead. There was no further scoring, and the Royals were in the World Series.

“It went from the highest high beating the Yankees in New York to the lowest low.”

— Willie Wilson8

After defeating the Yankees on October 10, the Royals waited in New York to see whether they would be playing Houston or Philadelphia in the World Series. They took the short flight to Philadelphia for the Series opener on October 14. Wilson had a terrible Series, striking out 12 times. Nevertheless, the Royals had a chance to extend the Series to a seventh game when they mounted a ninth-inning rally in Game Six. Down 4-1 going into the ninth, they loaded the bases with one out. Frank White popped out, bringing up Wilson, who was 0-for-3 with a walk in the game. He fouled off two pitches and then swung at missed at a high fastball and the World Series was over. By the time of Wilson’s next appearance in a World Series, his world had turned upside down. In the aftermath of the 1980 series, much was made of his 12 strikeouts, and the negativity extended into the following season.

The Royals got off to a bad start in 1981 and Wilson was batting .271 when the players went on strike after the games of June 11. The team was 20-30. When play resumed in August, Wilson and the Royals caught fire. In the 53 games after the strike, Wilson batted .332 and stole 26 bases. For the season, his average was .303. The Royals posted the best post-strike record (30-23) in the AL West and played a best-of-five series against Oakland to determine the AL West’s representative in the ALCS. Oakland swept the Royals and advanced.

Wilson had one of his best seasons in 1982. After pulling a hamstring during spring training and missing 24 of his team’s first 26 games, he returned to the lineup on May 9 and hit in 16 consecutive games. His hitting streak, including a start on April 19, stood at 17 games, and his batting average was .347 on May 26. It was his best start ever and he was selected for the All-Star Game for the first time. He entered the game in the fourth inning and was 0-for-2. At the All-Star break, he was batting .344, and the Royals trailed the division-leading Angels by one game. As the season drew to its conclusion, Wilson was contending for the league batting title with Robin Yount of the Brewers.

The Angels clinched the AL West on Saturday, October 2, the next to last day of the season. Going into the last game, Wilson had a four-point lead in the batting race (.332 to .328). Yount would need a 4-for-5 day to catch him. The Royals brain trust of Dick Howser and John Schuerholz advised Wilson to sit the day out. So, Wilson did not start in an otherwise meaningless game between Kansas City and Oakland. In his first four at-bats, Yount hit a pair of homers, a fly ball, and a triple while Wilson sat. Both games were in the late innings and if Yount got up a fifth time, a hit would put him in the lead.

That was when things got a bit dicey. The Royals began a stalling act with two outs in their half of the ninth inning. They were down by three runs and the outcome of the game did not matter. Manager Howser called batter Mark Ryal back to the dugout for a chat, and he was ready to insert Wilson into the game in the event Yount got the needed hit in his final at-bat. Opposing A’s manager Billy Martin, fully aware of the motivation for the stalling, phoned the Royals dugout and agreed to go along with the stall, making an unnecessary and prolonged visit to the mound to talk with his pitcher, Dave Beard. When word came that Yount had been hit by a pitch in his final plate appearance, Howser signaled Martin, and Billy left the mound. Beard got Ryal out on a grounder, the game was over, and Wilson had won the batting title, .3316 to .3307.

The negative image that surfaced when Wilson struck out 12 times in the World Series was further fueled by his failure to play the final game of the 1982 season. The ghosts of each would stay with him. Then, an off-field ghost entered the picture. Wilson began to experiment with cocaine. The experimentation was over by the beginning of the 1983 season and Wilson got off to a good start. Through May 25, he had played in each of his team’s 37 games and was batting .302. He was once again named to the All-Star team. In the All-Star Game, Wilson entered the game defensively in top of the seventh inning. He came to bat in the bottom of the seventh and drove in Lou Whitaker with a double. It was the 11th AL run as they won the game 13-3. It was Wilson’s final All-Star appearance.

On July 24 at New York, Wilson injured his shoulder diving for a ball hit by Roy Smalley in the fifth inning and came out of the game for a pinch-hitter in the top of the sixth. He missed a couple of games but returned to the lineup on July 27. In those three days, his world turned upside down. His voice had been recorded in a call to his former cocaine supplier and he had been questioned by police on July 25. The team was informed that Wilson and several other Royals were involved in the investigation. The rest of the season went by as a blur for Wilson, who batted .276 with 59 stolen bases.

After the season, Wilson faced charges related to cocaine and plead guilty to a misdemeanor count of attempting to buy cocaine, the charges being based on the wiretap evidence. In a time when there was little tolerance for cocaine use, especially by an athlete, Wilson was sentenced to a year in jail, of which nine months was suspended. He began serving his 90-day sentence on December 5, 1983. He was released nine days early, on March 1, 1984, from the federal penitentiary near Dallas, Texas.

Wilson was suspended by Commissioner Bowie Kuhn on December 13, 1983. The suspension was for one year, but it was subject to review on May 15. While suspended, Wilson worked out and met with team owner Ewing Kauffman, who proved to be a pillar of support through the crisis. The suspension was lifted on May 16, 1984, 33 games into the season. In his first game back, Wilson walked in the first inning. With Frank White batting, Wilson stole second base without a throw. White Sox pitcher Floyd Bannister then tried to pick Wilson off second base. Second baseman Julio Cruz misplayed the ball and it went into short center field.9 Wilson scored from second base, giving the Royals an early lead in a game they won 7-6. Wilson had another solid season, batting .301 and stealing 47 bases as the Royals won another AL West title. In the playoffs, Kansas City was swept by the Tigers in three games.

Despite his renewed success on the ballfield, Wilson’s trials off the field continued. During the 1984 season, he and his wife, Kathy, separated. They were divorced on February 19, 1987. Although he felt stress from his marital problems and the lingering criticism by fans of him for his drug problems, Wilson continued to contribute on the field. When he was separated from Kathy, he had a child out of wedlock. Mallori was born on February 5, 1985. Wilson married for the second time in 1988. He and Catherine had two sons, Trevor in 1992 and Max in 1995.

Early in the 1985 season, Wilson signed a lifetime contract with the Royals that would ultimately yield him $27 million by some estimates.10 The deal called for a four-year contract extension through 1989 with a salary of $1.25 million per year, of which $250,000 would be invested by a Royals minority owner. The money would effectively be used to provide an annuity to Wilson after his playing days. Within a couple of years of signing, Wilson, not feeling that he had made the best deal, elected to take a buyout.

On May 22, 1985, Wilson stole his 400th base, against the Texas Rangers. The Royals won the game, putting them two games above .500. The teams in the AL were tightly bunched but the Royals had trouble making headway. They were still two games above .500 as late as July 21 and were 7½ games out of first place.

A seven-game winning streak in late July moved the Royals into second place, and for the balance of the season they challenged the Angels for the AL West lead. Wilson was batting .285 at the end of August, and the Royals trailed the division leaders by 2½ games. But Wilson was not feeling well and, while his team was in Texas, took a penicillin shot. He had a bad reaction to the shot and missed the next 18 games. During the time he was absent from the lineup, the Royals went on a tear, winning 13 of 18 games and taking a two-game lead over the Angels.

When he returned to action, Wilson went into a slump, going 2-for-26 over six games. But by the time the Royals returned home for their last two series of the season, Wilson was back in stride with both his hitting and fielding. In the first of the two series, the Royals took three of four from the Angels at Kansas City and had a one-game lead going into their season-ending three-game series against Oakland. In the first two games, Wilson’s season was redeemed. In the first game he led off the third inning with a double and came home on a single by Jorge Orta to make the score 2-0. The Royals won, 4-2, to clinch a tie for the division championship.

The next day, before a home crowd of 32,949, the game went into extra innings. The day did not start out well as the Royals fell behind 4-0. Never in the season had the Royals come back to win from such a deficit. Wilson legged out an infield hit, and George Brett homered to cut the lead in half in the sixth inning, and the Royals evened things up in their next at-bat. The game went into the 10th inning. Although Wilson set a career high with his league-leading 21 triples in 1985 (the third of five times he would lead the league in triples), it was a single that proved the most memorable hit of his day and season. He came to the plate with two on and two out in the 10th inning and sent a Jay Howell fastball up the middle. Howell got his glove on the ball but was unable to catch it. The ball rolled over second base and into the outfield. Wilson rounded first, pumping his fist into the air as Pat Sheridan came in from third with the winning run that sent the Royals to the playoffs.11

In the ALCS, the Toronto Blue Jays won the first two games. In Game Three of the best-of-seven series, Wilson’s sixth-inning single was followed by George Brett’s game-tying homer, and the Royals won, 6-5. However, Toronto won the next game to take a 3-1 lead in the series. The Royals had to win the next three games, including the final two in Toronto, to advance to the World Series, and they did precisely that. Wilson had the most hits (9) of any Royals player in the series.

Against St. Louis in the World Series, the Royals lost the first two games at home. In Game Three, behind a strong pitching effort by Bret Saberhagen, the Royals won 6-1. The Cardinals won Game Four to go up 3-1 in the Series and once again the Royals had a formidable task. In game Five, Wilson’s first two at-bats proved productive. In the first inning, his single advanced Lonnie Smith to second and Smith subsequently scored the first run of the game. By the time, he came to bat in the second inning, the Royals led 2-1 and there were runners on first and second. Wilson, batting left-handed, tripled into the gap in right-center field, giving the Royals a 4-1 lead. Pitcher Danny Jackson shut down the Cardinals from that point.

The Royals’ 6-1 win took the Series back to Kansas City. They won Game Six with two runs in their last at-bat to force Game Seven and manhandled the Cardinals 11-0 in the finale to win their first World Series. They broke the game open with six runs in the fifth inning, during which Wilson got a run-scoring infield hit. His 11 hits in the Series led the Royals, and he was relieved that he cut his strikeouts down from 12 in 1980 to four in 1985. After the Series the Royals went to Washington and met with President Reagan and Vice President Bush.

In 1986, any problems of Wilson and his teammates were secondary, as manager Dick Howser’s illness left its mark on the team. It was brain cancer. After he managed the American League in the All-Star Game, it was evident that Howser could not continue. An 11-game losing streak from June 27 through July 8 took the Royals out of contention. Mike Ferraro took over as manager on July 17 and the team limped to a third-place finish, 16 games out of first place. Wilson hit .269 with 34 stolen bases.

The 1987 Royals were a bit younger with the addition of Bo Jackson and Kevin Seitzer. The team mourned Howser’s death on June 17. The core of older players who had been there when Wilson first arrived was further depleted when Hal McRae was released. Billy Gardner managed the Royals for most of the season, but the team was two games under .500 when Wilson’s former teammate John Wathan was named manager August 27. No team was dominating the AL West and the Royals were still in contention on Labor Day. They won nine of their last 11 games and finished the season in second place, two games behind the AL West champion Twins. Wilson led the league in triples with 15 and batted .279.

In 1988 and 1989, the Royals continued to add new talent to the mix. In 1988 they finished third. Wilson led the league in triples (11) for the last time and his batting average sank to .262. In 1989 Wilson played in fewer games (112) than in any season other than the strike-shortened 1981 season. The Royals posted a 92-70 record and finished in second place. In neither season had they made a serious run at the championship. And Wilson seemed to be nearing the end of the line. In 1989, at age 33, he batted only .253.

As the 1990 season began, Wilson was no longer playing regularly as Bo Jackson, Danny Tartabull, and Jim Eisenreich were the starting outfield. However, an early-season injury to Tartabull gave Wilson the opportunity to get into the lineup. In April he started 16 of his team’s 18 games and batted .345. Tartabull did not return to the lineup until May 19. By then Wilson’s bat had cooled off a bit and his average had slipped to .293. For the season, his last with the Royals, Wilson batted .290 and had 24 stolen bases, bringing his career total with the Royals to 612.

Under the terms of the contract Wilson had signed with the Royals, the team could pick up his option for the following season or release him. They elected to release him. The Oakland A’s wasted no time in signing Wilson and he was with them for two years. In 1991 he was a situational player, as the team was set with Dave Henderson, Jose Canseco, and Rickey Henderson in the outfield, and Wilson, primarily a singles hitter, was rarely asked to DH. He got into 113 games with 64 starts. He batted only .238 as the A’s, after three consecutive trips to the World Series, finished fourth in the AL West.

In 1992 Wilson became an important cog in the A’s machine as Dave Henderson hurt himself in spring training and was out for most of the season, getting into only 20 games. Wilson, at age 36, started 100 games, batted .270, and stole 28 bases. The A’s went 19-10 in August and took a 6½-game lead into September. They coasted to their fourth division championship in five years. In the best-of-seven ALCS, Oakland was defeated by Toronto in six games. Wilson played in each game, going 5-for-22 with seven stolen bases.

After the season, the A’s did not offer Wilson a contract extension and he signed with the Chicago Cubs. The Cubs were a younger team and Wilson was playing in the National League for the first time. He was also playing before fans who were far more boisterous than what he had experienced in Oakland over the prior two seasons.

Early in the season, Wilson received word that his grandmother, who had raised him in the early years of his life, had died. He returned to the team after the April funeral, but his playing time with the Cubs was not significant. He started only 39 games and had 237 plate appearances, his lowest total since 1978. He stole fewer than 20 bases in a season for the first time, and he played for a team that had finished below .500 the prior three seasons. On September 2 the Cubs were six games below .500 and 19½ games behind the division leaders.

Wilson was never a big home-run hitter, but his most memorable moment of 1993 involved the long ball. On September 6 the Cubs, having won three straight games, started a three-game series in Philadelphia. The fans, remembering Wilson’s being the goat of the 1980 World Series, were heckling him severely. That day he got a bit of revenge. In the top of the fourth inning, he doubled and scored a run that put the Cubs ahead 3-2. Two innings later, the Cubs scored three runs on consecutive homers by Steve Buechele, Wilson, and Steve Lake to make the score 7-2 in a game they won 7-6. The home run was the last of Wilson’s 41 career homers, and the only one he hit after leaving the Royals.

The Cubs went 20-8 over their last 28 games and finished the 1993 season over .500. Wilson batted .258. The Cubs released him on May 16, 1994. He had started only three games. His last appearance came on that day, and he went out with a flourish. He entered the game at San Diego as a pinch-runner in the bottom of the eighth inning and finished the game in center field. With the Cubs leading 4-2 and one out in the bottom of the ninth, Dave Staton of the Padres hit a fly ball to deep left-center field. Wilson, in full gallop, reached out and grabbed the ball. Pitcher Randy Myers struck out the next Padres batter to end the game.

Wilson finished his 19-year career with 2,207 hits. His 668 stolen bases rank him 12th on the all-time list. His lifetime batting average was .285.

By the time Wilson left baseball in 1994, he had remarried and lived in Kansas City. He invested in a Toronto-based telecommunications company, and that turned out to be a bad investment. Other investments, including a restaurant in New Jersey, also did not work out, and he was bleeding financially. Wilson tried his hand at coaching in the minor leagues but was unsuccessful. He was a coach for the Syracuse Chiefs, Toronto’s Triple-A affiliate, for most of 1997 before being reassigned to Dunedin in the Class-A Florida State League.

By 1999, Wilson was on the verge of bankruptcy. He was also using cocaine. He sought help for his drug problem at the Shawnee Mission Medical Center and got clean. In 2000, not long after his drug rehab, he was inducted into the Royals Hall of Fame, but his problems with money were far from over. He filed for bankruptcy, and during the process was stripped of his baseball memorabilia. An auction in April 2001 raised $30,570. Wilson’s World Series ring was sold for $16,250.12 The problems he faced during this period put a stress on his marriage, and his wife and children moved to Toronto to be closer to her family.

Wilson got back into baseball in 2001 as a coach in the Arizona Diamondbacks organization. He was with the South Bend Silver Hawks in the Class-A Midwest League. The team did well, and in 2002 Wilson was promoted to a higher-level Class-A team, the Lancaster JetHawks in the California League. Toward the end of the season, he was released after a confrontation with one of the players.

Wilson relocated to Toronto and lived near his wife and children, but in the summer of 2004, he returned to New Jersey and established a baseball camp. His camp proved to be a success and he stayed with it for several years, bringing in former teammates to work with the children. He moved back to Kansas City, where he became more involved with the Royals, gave clinics to youngsters, and worked with the Negro League Baseball Museum. In 2008 the Royals named their minor-league baserunning award in Wilson’s honor.

In September 23, 2014, at a book signing and talk after the release of his autobiography, Wilson received a surprise. Helen Mohr, who oversees the Willie Wilson Foundation, presented him with a 1985 World Series ring. About 100 of his friends had funded a recasting of a new ring to replace the ring that had been auctioned off in 2001.13

At age 63 in 2018, Wilson was at peace with himself and spent as much time with his five grandchildren as his schedule allowed.

Sources

In addition to the sources shown in the notes, the author used Baseball-Reference.com, the Willie Wilson file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, and the following sources:

Black, Del. “Royals Outfield to Depend on Willie Wilson,” The Sporting News, March 25, 1978: 53.

Bordman, Sid. “Royals’ Speedy Wilson Setting Hot Bat Pace,” The Sporting News, August 18, 1979: 13.

Fish, Mike. “Wilson Is Basking in Second Chance,” The Sporting News, May 6, 1985: 17.

Kaplan, Jim. “Will He Be Willie Again?” Sports Illustrated, February 9, 1981: 78, 81.

Looney, Douglas S. “Fleetest of the Royal Fleet,” Sports Illustrated, April 24, 1978: 34.

McKenzie, Mike. “Wilson’s Fuse Always Burning,” The Sporting News, October 11, 1982: 49.

Rock, Steve. “Bittersweet Blessing: Wilson Glad to Go in Royals’ Hall, but Expected More from Team,” Kansas City Star, June 26, 2000: C1.

“Our Opinion: Some Mixed-Up Priorities,” The Sporting News, October 18, 1982: 6.

Notes

1 Peter Gammons, “Continual Spur Necessary for Whippet Willie Wilson,” The Sporting News, May 24, 1980: 23.

2 Mike DeArmond, “Injuries Fail to Quell Enthusiasm for Royal Farm Hands,” Kansas City Star, August 6, 1974: 10.

3 Del Black, “Royals Farm Teams Play Follow Their Leader,” Kansas City Star, August 4, 1976: 18A.

4 Associated Press, “Royals Win Squeaker in 10th on Clutch Brett Hit,” Baton Rouge Morning Advocate, September 10, 1976: 4-C.

5 Willie Wilson (with Kent Pulliam), Inside the Park: Running the Base Path of Life, (Olathe, Kansas: Ascend Books, 2013), 75.

6 Jim Kaplan, “K.C. Takes Off on Willie’s Wings,” Sports Illustrated, September 10, 1979: 26.

7 The Sporting News, October 18, 1980: 41.

8 Wilson with Pulliam, 100.

9 Kaplan, “Taking Steps to Solve the Drug Dilemma,” Sports Illustrated, May 28,1884: 36.

10 Bob Nightingale, “Wilson’s Struggles Extend Beyond the Baseball Field,” Kansas City Star, June 30, 1986: 1B.

11 Mike Penner, “Royals Win West Again — Angels Don’t Again: Kansas City Wraps It Up in 10th, 5-4,” Los Angeles Times, October 6, 1985: 1.

12 Associated Press, “Wilson Auction Fetches Big Bucks,” Springfield (Missouri) News-Leader, April 24, 2001: 3C.

13 Blair Kerkhoff, “Former Royal Willie Wilson Surprised with New World Series Ring,” Kansas City Star, September 24, 2013.

Full Name

Willie James Wilson

Born

July 9, 1955 at Montgomery, AL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.