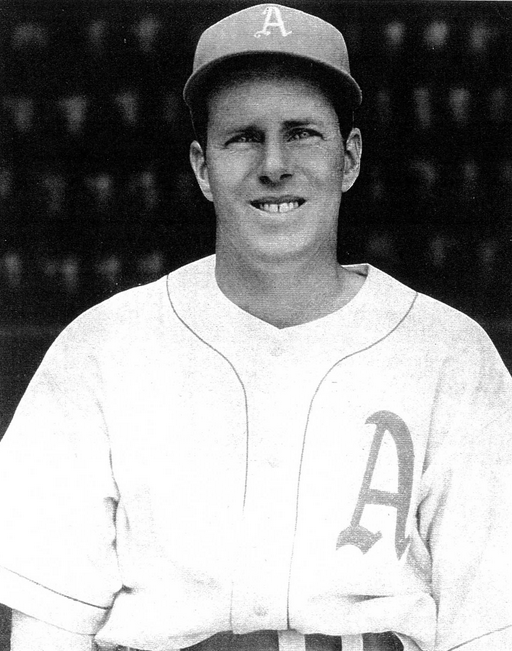

Woody Wheaton

The rich farm country surrounding Lancaster, Pennsylvania, attracts visitors, and some of those visitors remain and thrive in the area. Many baseball teams at any number of minor-league and independent levels have called Lancaster home, dating as far back as 1884. In 1940 the Lancaster Red Roses came to town from Hazleton, Pennsylvania, and played in the Class B Interstate League. They played their home games at Stumpf Field, not far from the local Armstrong plant.

The rich farm country surrounding Lancaster, Pennsylvania, attracts visitors, and some of those visitors remain and thrive in the area. Many baseball teams at any number of minor-league and independent levels have called Lancaster home, dating as far back as 1884. In 1940 the Lancaster Red Roses came to town from Hazleton, Pennsylvania, and played in the Class B Interstate League. They played their home games at Stumpf Field, not far from the local Armstrong plant.

Woody Wheaton was the team’s most popular player. He never really left Lancaster and became a fixture in the community after his career in Organized Baseball was over.

Elwood Pierce “Woody” Wheaton was born in Philadelphia on October 3, 1914, the fourth of seven children. His parents were Walter R. Wheaton and Jennie Stevens Wheaton. His father, who worked at the Philadelphia Navy Yard, was the organizer of Delhi Grotto, a fraternal organization, and his mother was the president of the organization’s ladies auxiliary. Walter was also active in semipro ball in the Drexel Hill area of Philadelphia and was still playing when Woody made his debut in professional baseball in 1936.1 Woody had two sisters (Isabelle and Jane) and four brothers (Walter, Edward, Robert, and Henry).

Wheaton graduated from Upper Darby High School in 1935 and began a career that would take him to 15 towns, mostly small, during the next 17 years. In high school he had been a pitcher, but in a 1936 tryout with the Philadelphia Athletics, Connie Mack converted the left-hander into an outfielder.2 For a short time, Wheaton was also a professional soccer player as a member of the Philadelphia Nationals of the American Soccer League.3

The first stop for Wheaton was Williamsport (Pennsylvania) in the Class-A New York-Pennsylvania League, in 1936. He was known as Shorty in those days.4 Although listed as 5-feet-8½, he was actually closer to 5-feet-6. Batting leadoff and hitting from the left side of the plate for the Grays, the Philadelphia A’s farmhand hit .310 in his first year of professional ball, playing for Mike McNally. After being held hitless on Opening Day, Wheaton collected the first four hits of his professional career in the next game, April 30 as Williamsport defeated Hazleton 14-11 in 10 innings. That was the beginning of a 10-game hitting streak during which he went 22-for-49. Woody wasn’t a big home-run threat, and he had only two homers in 1936. As the first half of the season came to a close, Wheaton’s bat was hot and he had his first five-hit game on June 26, going 5-for-5 in a 7-6 win over Wilkes-Barre.5

Wheaton was forced from the game on August 23 when he was struck by a pitch from Scranton’s Milt Shoffner, but was back in action shortly as the Grays contended for the second-half championship but came up short, finishing in third place. At the end of the season, when the league’s All-Star team was chosen, Wheaton received an honorable mention nod.6

Wheaton began the following season back with Williamsport, but he was unable to replicate his 1936 performance. Through eight games, he was batting .188 and was benched. He finally was released on June 7. His batting average had improved, but only slightly, to .228 and he had been benched in eight of his team’s 37 games. Shortly thereafter, Wheaton signed with another New York-Penn League team, first-place Elmira, affiliated with the Brooklyn Dodgers, and batted .270 in 97 games with the Pioneers. His combined average for the season was .257.

In 1938 Wheaton split his time between three teams in the Dodgers organization. He opened the season with Winston-Salem in the Piedmont League, and was traded back to Elmira on May 14. (The New York-Pennsylvania League had been renamed the Eastern League.) On August 13 he moved on to Dayton, in the Mid-Atlantic League, where he finished the season. His overall batting average was .262.

The next season Wheaton joined the Hazleton Mountaineers in the newly formed Inter-State League and would spend five seasons in that league. In 1939 he batted a career high.428, and led the league in batting average, base hits (185), and triples (16). He returned to Hazleton in 1940. In June, the team relocated to Lancaster and there became known as the Red Roses. After finishing fourth during the regular season, they defeated Wilmington and Reading in the playoffs to capture the league championship. In the third game of the final series, against Reading, Wheaten drove in the only run in a 1-0 win. Wheaton was with the Red Roses through 1943.

In 1941 Wheaton and the team got off to a fine start on April 30 against Wilmington, winning 4-3. Wheaton went 4-for-4, scored once, and hit three doubles. However, the team fared poorly trying to defend its championship of the prior year, finishing in last place. Wheaton was Lancaster’s sole representative on the All-Star team in the league’s all-star game.7

He was back with the Red Roses in 1942 and got off to a resounding start. On Opening Day, April 29, he went 4-for-5 with three runs scored, two doubles, and an RBI as Lancaster defeated Wilmington, 7-1.8 The Red Roses finished the season in fifth place, but that didn’t stop Woody from going to the playoffs. When playoff-bound Harrisburg lost two players to the Army, Wheaton and Dennis “Red” Gleason stepped in for Harrisburg.9 For the season, Wheaton posted a .256 batting average.

Just before the 1943 season began, the popular Wheaton was appointed Lancaster’s manager, and on Opening Day he was presented with a diamond ring.

That season, as newspapers headlined the Allied invasion of Italy, Wheaton had the season of his life, as did his team. As the “Yanks Gain Ground at Salerno” headline streamed across the top of the Lancaster Intelligencer-Journal on September 14, in slightly smaller print on the front page was a headline stating “Lancaster Wins First Inter-State Pennant.”10

But it didn’t start out that way. With the country at war, there was a shortage of ballplayers at all levels and manager Wheaton found himself with only three established players at the beginning of the season. The team lost seven of its first eight games and was in last place in the six-team league.

As he recalled for a sportswriter, “When we opened spring training we only had three ballplayers – [future Hall of Famer George] Kell, [pitcher Charles “Major”] Bowles and myself. Arthur Ehlers, who later became Inter-State League president, sent Steve “Splinter” Gerkin [who went on to pitch a no-hitter on June 28] here from Baltimore. I talked to Tom Kain, a friend, who was managing Norfolk of the Eastern League for the Yankees, and I told him I needed some players. He sent Johnny Greenwald, Vic Males and Irv Levy and a pitcher, Bill Davis, here.

“[Business] manager Bill Cowdrick made a deal with Chattanooga [actually Knoxville] of the Southern League and obtained [Lew] Flick for a pitcher, [Ed] Vosheski, by name. Branch Rickey, a long-time friend, sent Bill DeMars to Lancaster for Brick Hoffner. We signed [former Philadelphia A’s pitcher] Les McCrabb, and when [Paul] Tex Kardow called me and said he was looking for a job, we signed him immediately. Lew Krausse came here from Elmira.

“This all happened in pretty much of a hurry. We were desperately in need of some established ballplayers. As I recall we only won about five games of our first 20 [actually, the team was 8-12 through 20 games] and we were in deep trouble. But my friends in baseball all came through for me and got us going with a team that proved to be one of Lancaster’s finest.”11

The team had sunk to 8-17 in late May when things began to turn around. On June 2, when McCrabb made his first start for the Red Roses, there were four other new faces in the lineup. Johnny Greenwald was at first base, Carl McQuillen and Flick joined Wheaton to patrol the outfield, and Steve Sefick was behind the plate as the team defeated Trenton, 6-1.12 On June 13, Wheaton, in a 6-1 win over York, provided the power with a home run to right-center field that was said to be the longest home run ever hit at Stumpf Field.13

The Red Roses put together a nine-game winning streak in late June to surge into contention. On June 30 Wheaton took to the mound, pitched a complete game, and drove in the winning run as Lancaster scored four runs in the ninth inning to defeat Hagerstown, 6-5.14 They moved above .500 for the first time on June 27. On July 7 against Hagerstown, the Red Roses scored 28 runs on 30 hits. Wheaton went 6-for-7 and scored six runs. In a three-game sweep at York on July 10-11, Wheaton pitched the last 6⅔ innings of an 11-inning win on July 10 and went 6-for-12 with a double, two homers, and seven RBIs in the series. On July 14, he went to the mound with one out in the first inning and his team down by three runs. He pitched the final 8⅔ innings as Lancaster came back to win, 11-8. After a doubleheader sweep of Hagerstown on July 25 the Red Roses took over first place for good.

It was, of course, a war year and one just never knew what to expect in the way of personnel. So it was that on June 16 the Red Roses lost a 1-0 decision to York in the first game of a doubleheader.15 What made this remarkable was that the York pitcher, who made his season’s debut that day, had begun his professional career in 1909 with York and had last pitched in the majors in 1918. He had returned to York in 1923, hurled 49 consecutive scoreless innings in 1924, and, in 1943, Thomas Edward “Lefty” George, who turned 57 during the course of the season, pitched in 21 games for York. His record for the season was 7-8, bringing his minor-league record to 300-280. Wheaton was manager of the West squad in the league’s all-star game on August 9 and selected George to start the game four days shy of his 57th birthday.16

Lancaster won the postseason playoffs. Wheaton, in addition to managing the Red Roses (83-55) to the pennant, topped the league’s pitchers with a 13-3 record and batted .325 with 167 hits.

Lancaster had a working arrangement with the Philadelphia Athletics who could purchase three players of its choice each year.17 So it was that at the end of the 1943 minor-league season, Wheaton joined the Athletics, along with George Kell (who had batted .396) and Lou Flick (a .375 batter). They joined Major Bowles (19-14) who had been purchased by the A’s earlier 18 Wheaton, Flick, and Bowles played in the major leagues with the Athletics only during the war years. Kell went on to a Hall of Fame career.

During the war Wheaton was classified as 4-F, due to high blood pressure and an “athletic” heart (extremely low pulse).19

After joining the Athletics, he made his major-league debut on September 28, 1943, just a few days before his 29th birthday, and went 0-for-5 in a win over the St. Louis Browns. His first hit came the following day, an RBI double off Detroit’s Rufe Gentry. In seven games, he batted .200 (6-for-30) with two doubles and two RBIs.

In 1944 Wheaton started in each of the Athletics’ first eight games. On Opening Day, April 18, against the Washington Senators, he went 2-for-5 in a game that went 12 innings. The A’s won, 3-2, and Wheaton figured in the first two runs. 20

On April 25 the Athletics stormed back from a 4-0 deficit against the New York Yankees, scoring seven runs in the final two innings to win the game, 8-4, at Yankee Stadium. Wheaton had two hits, including a two-run single off Ernest “Tiny” Bonham that gave the A’s a 5-4 lead in the eighth inning and a double in the ninth when the A’s put the game out of reach. Three days later, the A’s were at Fenway Park. Wheaton got the start in center field and the game went into extra innings with the score tied 5-5. Seven times, Wheaton came to bat, and seven times he came up empty. Twice, he hit into double plays. The game went into the 16th inning. The A’s loaded the bases, and up stepped Wheaton, who promptly singled off Clem Hausmann to drive in two runs and give the A’s the 7-5 win.

However, Wheaton was not hitting for a good average, and his .176 (6-for-34) mark at the end of April earned him a place on the bench. He had only one other start during his time with the A’s, who finished the season in fifth place with a 72-82 record.

Wheaton was called on as a relief pitcher on several occasions, first appearing against the Yankees on June 13, giving up three runs in a five-inning stint. He did not factor into the decision.

By July, Connie Mack’s squad was so short on pitching that Wheaton was pressed into service as a starter against the St. Louis Browns on July 6. Although his team lost, 5-0, his effort was not without merit. In his first and only starting assignment, he pitched all nine innings. After giving up a three-run homer to Vern Stephens in the first inning, he pitched “splendid ball, allowing only two runs over his final eight innings.”21

In 30 games in 1944, Wheaton batted .186 with 11 hits in 59 at-bats. As a pitcher, he appeared in 11 games, was 0-1, and had a 3.55 ERA.

After his time with the A’s, Wheaton returned to the minors and played through 1952, serving as player-manager for a number of teams. In 1945, with the Buffalo Bisons in the International League, he batted .305 in 103 games. The next season he became the player-manager of a Tigers farm team, the Rome (New York) Colonels in the Class C Canadian-American League. He batted .294 and pitched to a 3-4 record. The team finished in third place (in an eight-team league) with a 72-52 record. The Colonels were defeated in the first round of the postseason playoffs.

In 1947 Wheaton managed Moline (Illinois) in the Class-C Central Association until July 14, when he exchanged managing jobs with Joe Glenn and moved on to Martinsville (Virginia) in the Class C Carolina League. In 1948 he was no longer a manager and signed on with the Welsh Miners of the Class-D Appalachian League as a pitcher-outfielder. As a pitcher, he went 14-6, and as a hitter, he batted .357.

Wheaton’s performance in 1948 earned him a promotion back to the Class-B Interstate League where he managed the Hagerstown (Maryland) Owls, who were affiliated with the Washington Senators. His numbers were off from the prior year as he batted .257 and went 9-13 as a pitcher.

Back in the Athletics organization in 1950, Wheaton started with Welch (West Virginia) in the Appalachian League, where he batted .260, then was promoted to West Palm Beach in the Class-B Florida International League, where his average plunged to .178. As a pitcher he was 4-6 at Welch and 8-9 at West Palm Beach.

Wheaton was 12-6 with West Palm Beach in 1951. In 1952 he was back in the Inter-State League, with the Harrisburg Senators. The ballclub was in a dire financial situation and Wheaton, who had joined the team as a pitcher-outfielder, was appointed manager after the league took over the team in August. The team and league folded at the end of the season, and Wheaton’s career ended as well.

Wheaton’s minor-league numbers were impressive. In his 17 seasons he batted .297 with 1,810 hits. As a pitcher he went 90-77 with a 3.56 ERA. After his minor-league career ended, he went to work for the Armstrong Cork Company in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, and retired in 1981. He also conducted baseball clinics in the Lancaster area. In 1962 Wheaton was assistant baseball coach at Franklin and Marshall College in Lancaster, and assumed the head-coaching position a year later. He coached at F&M through 1970.

Wheaton was married to his wife Helen, and they had a daughter Helen Lynne, who was born on July 18,1945. Wheaton had adopted daughter Barbara, Helen’s daughter from a previous marriage, when he married Helen.

A boating enthusiast over the years in Maryland, Wheaton was a member of the Northeast Yacht Club. He owned boats from 24- to 32-footers, which required expert navigation, as well as a 14-footer, which he used for fishing and crabbing.

Also a singer, Wheaton performed with Tiny Wright’s big band, Jack Frank and the Majors, the Savoys, and Nite People.

He died on December 11, 1995, in Lancaster at the age of 81.

This biography originally appeared in “Who’s on First: Replacement Players in World War II” (SABR, 2015), edited by Marc Z. Aaron and Bill Nowlin.

Sources

Baumgartner, Stan, “Browns Blank Athletics 5-0: Muncrief Wins 8th, Defeats Wheaton; Stephens Homers,” Philadelphia Inquirer, July 7, 1944, 19.

Basenfelder, Don, “Wheaton and Kell Bloom as Red Roses,” The Sporting News, September 9, 1943, 7.

Colley, Frank, “Wheaton Replaces Lacy as Owls Manager,” Morning Herald (Hagerstown, Maryland), January 6, 1949, 10.

Crudden, George, “Wheaton, Roses Thrilled the Area – Flashback,” Intelligencer-Journal (Lancaster, Pennsylvania), January 18, 1990.

Martin, Jack, “Lancaster Wins First Inter-State Pennant,” Intelligencer-Journal, September 14, 1943, 1.

Martin, Jack, “Three Lancaster Aces, Kell, Wheaton, Flick, Bought by Athletics,” Intelligencer-Journal, September 28, 1943, 10.

Vulopas, Joseph, “The Pitch – ‘Bottom of the Ninth’: A Time for Miracles,” Lancaster New Era, December 14, 2005.

Woody Wheaton obituary, Intelligencer-Journal (Lancaster, Pennsylvania), December 13, 1995

The Gazette and Daily (York, Pennsylvania).

Intelligencer-Journal (Lancaster, Pennsylvania).

Morning Herald and The Daily Mail (Hagerstown, Maryland).

Philadelphia Inquirer.

Pottstown (Pennsylvania) Mercury.

New York Times.

Scranton Republican.

The Sporting News.

Sunday Morning Star (Wilmington, Delaware).

Ancestry.com

Baseball-Reference.com

Email correspondence from Helen Lynne Wheaton Hackman, daughter of Woody Wheaton – December 4, 2017

Notes

1 Pottstown Mercury, September 14, 1936, 5.

2 Don Basenfelder, The Sporting News, September 9, 1943, 7.

3 Alan Gilbert, “Baseballers, Farmington to Clash; Blue Seek to ‘Overcome Hurdles,’” Franklin and Marshall College Reporter, March 29, 1968, Spring Sports Supplement, 1.

4 Joe Polakoff, Scranton Republican, May 2, 1936, 14.

5 The Gazette and Daily, June 27, 1936, 8.

6 Scranton Republican, September 7, 1936, 12

7 The Daily Mail, August 1, 1941, 8.

8 The Sporting News, May 7, 1942, 16.

9 George Kirschner, The Sporting News, September 17, 1942, 5.

10 Intelligencer-Journal (Lancaster, Pennsylvania), September 14, 1943, 1.

11 George Crudden, Intelligencer-Journal, January 18, 1990.

12 Intelligencer-Journal, June 3, 1943, 10; Lancaster New Era, June 3 1943.

13 Lancaster New Era, June 15, 1943, 12.

14 Intelligencer-Journal, July 1, 1943, 11.

15 The Morning Herald, June 17, 1943, 4.

16 The Daily Mail, August 5, 1943, 13

17 George Kell, Hello Everybody, I’m George Kell (Champaign, Illinois: Sports Publishing, 1998), 23.

18 The Star and Sentinel (Gettysburg), October 2, 1943, 3.

19 Basenfelder.

20 The New York Times, April 19, 1944, 18.

21 Stan Baumgartner, Philadelphia Inquirer, July 7, 1944, 19.

Full Name

Elwood Pierce Wheaton

Born

October 3, 1914 at Philadelphia, PA (USA)

Died

December 11, 1995 at Lancaster, PA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.