Buffalo Bisons team ownership history

This article was written by Charlie Bevis

This article was published in the Team Ownership History Project

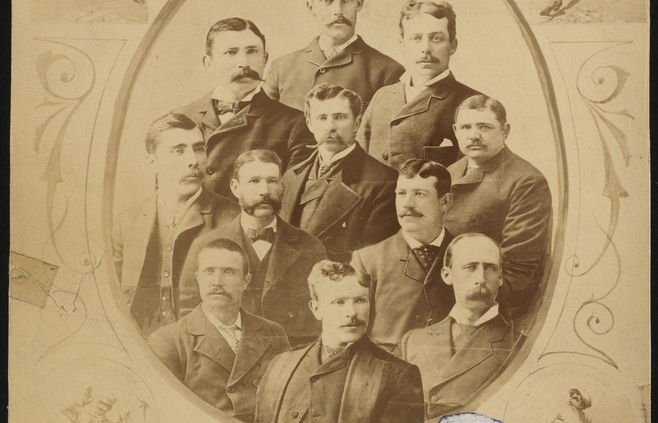

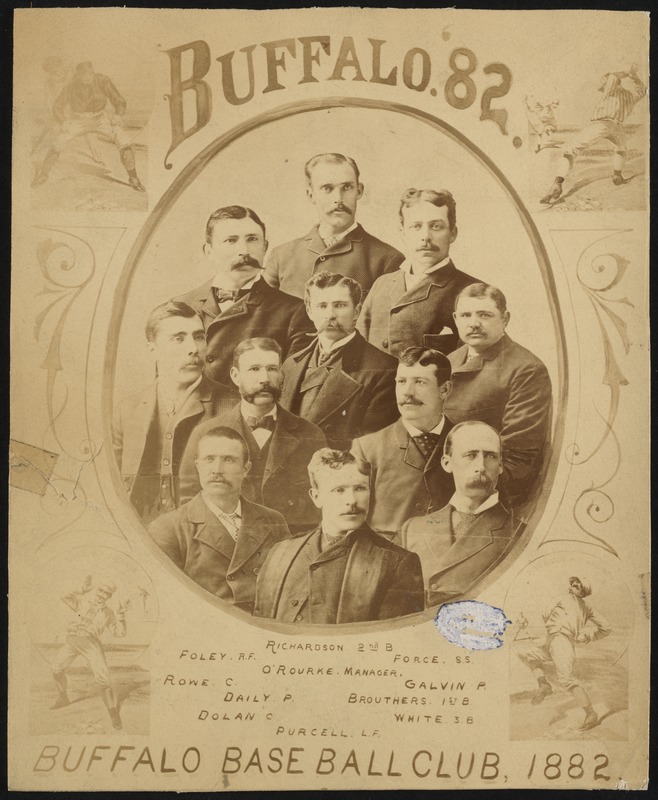

1882 Buffalo Bisons team portrait. Players are: outside, clockwise from top: Hardy Richardson, second baseman, Davy Force, shortstop, Pud Galvin, pitcher, Deacon White, third baseman, Purcell, left fielder, Tom Dolan, catcher, Jack Rowe, catcher, Foley, right fielder. Inside, clockwise from top: O’Rourke, manager, Dan Brouthers, first baseman, One Arm Daily, pitcher. (Courtesy of the Boston Public Library, Michael T. “Nuf Ced” McGreevy Collection)

Competing in the National League from 1879 to 1885, the Buffalo, New York, ballclub was relatively successful on the playing field, posting a winning record five times during its seven-year tenure. The club, though, consistently struggled to achieve financial success, earning a decent operating profit in just one of those seven years. The lasting legacy of this defunct Buffalo ballclub was its leadership in scheduling holiday doubleheaders and the use of discounted-ticket practices to attract women and children to the ballpark.

The origin of the 1879 Buffalo NL club was the Buffalo Base Ball Association (BBBA), organized in July 1877, which operated an independent professional team and turned a small $490 operating profit for the 1877 season. The BBBA was a stock company, with “the capital stock of the club mainly invested in its ball grounds and improvements, costing between $4,000 and $5,000.” This ballpark, built in 1878, was located two miles north of downtown Buffalo on leased land along Rhode Island Street, between Fargo Avenue and West Avenue. This facility was known as the Buffalo Base Ball Grounds for its first four years of existence.1

The financial goal of the BBBA in 1877 and 1878 was to break even, not necessarily to turn a profit, a common practice in the pre-professional days of the city’s vaunted Niagara amateur ballclub, where club members stood ready to backstop any shortfall in baseball operations if necessary. This break-even philosophy carried over to the BBBA in 1879, where the club directors were more sportsman than businessman and the stockholders were the financial safety net.

For the 1878 baseball season, the BBBA placed a Buffalo team in the International Association and finished the season as league champion. Financially, though, the BBBA posted a $200 operating loss in 1878 as $16,795 of disbursements exceeded the $16,595 of total receipts. (These figures do not include the construction costs of the ballpark or the cash received from stock sales.) Admission to the Buffalo ballpark in 1878 cost just 25 cents, with an additional 15 cents for grandstand seating.2

For the 1879 season, Edward B. Smith was named president of the BBBA, with John B. Sage the vice president, Edward R. Spaulding the treasurer, and Henry S. Sprague the secretary. The seven-man board of directors consisted of Smith, Sage, Spaulding, Sprague, Howard H. Baker, John Van Velsor, and John R. Kenny. Four of the directors – Smith, Sage, Spaulding, and Van Velsor – were former ballplayers on the old Niagara club, steeped in the city’s sportsman attitude toward competitive baseball. Smith’s occupation was insurance agent, while Sage worked as a lithographer.3

In December 1878 the BBBA directors voted to apply for membership in the National League, reasoning that “the only place for a first-class club is the League,” despite the serious financial risk associated with the “increase of the price of [ballpark] admission to fifty cents,” the minimum level permitted by the League. The Buffalo Commercial Advertiser expressed concern that “a great many of those who cheerfully paid 25 or 40 cents to see the games last season will decline to go next season if the prices are 50 and 65 cents.” With Smith and Sage both in attendance, the National League ballclub owners voted at a December 1878 league meeting to accept the Buffalo ballclub for the 1879 season.4

In March 1879 Sage and Smith switched positions, with Sage becoming the president for the remainder of the 1879 season and Smith assuming the role of vice president. In modern histories of the Buffalo ballclub, Smith is often erroneously referred to as the president for the entire 1879 season, likely because the Spalding Guide published the original slate of club officers.5

The BBBA acquiesced to the league-mandated ballpark admission charge of 50 cents in 1879, but lowered the supplemental cost for grandstand seating to 10 cents so that the top cost for the best seats was just 60 cents for the club’s inaugural National League season. Since this was a 50 percent increase from the 1878 cost of 40 cents, many people did balk at paying the higher price to attend one of the 42 home games on the 1879 schedule. In June the BBBA began selling a $4 ticket good for 10 admissions plus a free scorecard each time. This lowered the total cost for one game to 50 cents (40 cents general admission, 10 cents grandstand, free scorecard), which was just 5 cents more than the 45 cents it had cost in 1878 (25 cents general admission, 15 cents grandstand, 5 cents for scorecard).6

Since Sunday ballgames were prohibited by both New York state law and National League policy, there was only one surefire big attendance date on the Buffalo home schedule – the Independence Day holiday, when everyone had the day off from work and could go to the ballpark. At the holiday game on July 4, 1879, the BBBA announced that 3,315 people had filed through the turnstiles at the Buffalo Base Ball Grounds. While this was the largest crowd of the 1879 season, it wasn’t enough to reverse the dour financial outlook facing the BBBA.7

At a special BBBA stockholder meeting in August, Smith estimated “that $3,000 would be required to place the club on a sound financial basis and carry it through in good shape to the commencement of the next season.” The stockholders agreed to a voluntary $20 subscription by each of the 150 or so stockholders, in exchange for free admission to all ballgames in 1880. They also requested that the directors “urge the League” to adopt an admission policy of 25 cents, which they saw as the key to the BBBA’s financial success.8

The Buffalos (as the team was then called by the press before the Bisons nickname became popular) finished in third place in the National League standings at the end of the 1879 season, on the strength of the right arm of pitcher Pud Galvin. While the BBBA’s $3,000 expected deficit was covered by stockholder subscriptions, this approach was not a sustainable fiscal policy for the future. Buffalo, though, was not alone in its financial plight.

Since nearly every National League ballclub lost money in 1879, the club owners met in Buffalo in late September to discuss ways to improve profitability. Sage represented Buffalo at this meeting, where the discussion focused on how to rein in player salaries. The owners adopted several restrictions, the most egregious being the five-man rule, which stipulated that “each club will name five men of their present team who should be inviolate, that is no other club could have a right to approach or sign them without the consent of said club.” This initial vestige of the reserve clause in the future standard player contract negated player leverage in salary negotiations and effectively constrained salaries.9

At the December league meeting, Sage and Smith proposed resolutions to lower the league’s mandated 50-cent admission charge, since the BBBA still viewed this as a revenue impediment. While their proposals were voted down, the other club owners did stipulate that the 50-cent levy applied just to “each adult person,” which gave Buffalo some room to maneuver (especially with its then understood male-only implication). While the BBBA directors considered leaving the National League to return to the lower-status International Association, they decided to remain in the League by accepting the operating principle that “the kind of people whom it is desired to attract are they who are willing to maintain honorable sport by paying a liberal price toward its support.”10

For the 1880 season, the same slate of officers and directors was reelected to operate the BBBA, with Sage in charge of securing players. The five-man rule was of little help, though, as catcher John Clapp and pitcher Galvin both jumped to non-League clubs. Sage did retain Hardy Richardson and Jack Rowe, one-half of the vaunted Big Four of future incarnations of the Buffalo team. Sage eventually had to overpay Galvin to get him to return to the Buffalo team in late spring.11

The 1880 season was dismal: Buffalo finished in seventh place in the league standings and the BBBA incurred a sizable financial loss in the ledger books. In early September, the Buffalo Express reported that “it will take about $1,500 to run the team through the rest of the season.” Stockholders were approached for another round of subscriptions, as the directors hoped to raise $5,000 not only to cover the 1880 deficit but also to provide an economic cushion for 1881.12

On the salary-reduction front, Smith objected to the continuation of the five-man reserve rule at an early October league meeting. “Mr. Smith of Buffalo was opposed to the rule,” the New York Clipper reported. “The Buffalo representative opposed it vigorously and made a desperate fight, but he was outnumbered.” It was a last-ditch effort by sportsman Smith to salvage player rights. However, his stance was in opposition to that of many BBBA stockholders, who believed salary reduction was the easiest way to improve club profitability, since salaries typically equaled half of club expenses. Smith did not remain club vice president for much longer.13

On the same night as the league meeting, the BBBA stockholders demonstrated their lost confidence in Smith and Sage by voting to make sweeping changes in the board of directors for the 1881 season. The stockholders ousted all seven men on the existing board and replaced them with more business-minded men. The board of directors for 1881 consisted of Josiah Jewett, James Moffat, Spencer Clinton, John Bush, Albert Jones, James Mugridge, and Richard Evans Jr. The new board named Jewett as president and Moffat as vice president, with Elihu Spencer the secretary and George Hughson the treasurer.14

Jewett came from a wealthy family that operated a stove manufacturing business as well as the Bank of Buffalo. Moffat operated a local brewery (which bottled Moffat’s Pale Ale) while Hughson was engaged in real estate. Jewett and the other BBBA directors differed from prior management. They were capitalists and operators of midsized commercial enterprises, whereas Smith and Sage were small-business owners and sportsmen actively engaged in archery and riflery clubs as well as the baseball club. Jewett’s group believed the BBBA should be a profit-making operation, not a sporting venture, to generate national recognition and thus enhance opportunity for Buffalo businessmen.15

The new officers of the BBBA relinquished many of the baseball-related functions performed by the previous management (including salary negotiation with the players) and delegated them to a professional manager. They initially hired Frank Bancroft, who had excelled as full-time nonplayer manager of the Worcester ballclub in 1880. However, Bancroft jilted Buffalo and instead took the manager job with the Detroit team. The BBBA then hired Jim O’Rourke to perform the same mission (despite O’Rourke being a player-manager), which resulted in the team being stronger on the field, with the acquisition of Deacon White and Dan Brouthers, the second half of the Big Four, and the BBBA becoming more financially viable.16

One of the first financial matters undertaken by the new management was to increase the BBBA’s capital stock by $2,000 to bring the total outstanding capital stock to $7,000. It’s not clear how many shares of the $50 stock were actually bought, nor what management did with the money.17

A second important financial matter initiated in 1881 was the addition of a second game on the Independence Day holiday, the biggest payday on the Buffalo home schedule. On July 4, 1881, Buffalo played morning and afternoon games against the Troy, New York, ballclub. This twin bill was “the first separate-admission morning-afternoon two-game set on the Independence Day holiday” in major-league history. The combined attendance for both games was reported to be 4,248 people, roughly 15 percent of the club’s total home attendance for the entire season. For the remainder of its existence, whether the BBBA earned a financial profit for the season was highly dependent upon home gate receipts from the Independence Day twin bill.18

Hughson, the BBBA treasurer, released a detailed 1881 financial statement to the Buffalo press. The statement showed total receipts of $28,632 and total disbursements of $25,954, which ostensibly indicated a net profit of $2,678 (the “cash on hand” at end of period). However, contained within the receipts was a line for “stock subscriptions” equaling $4,465, and within disbursements a line for “paid 1880 club for lease and property” equaling $1,842. The net of these two items totals $2,623 – the actual net cash infusion from stockholder subscriptions – and comprises 98 percent of Hughson’s specified $2,678 profit. More realistically, therefore, operating profit totaled just $55, essentially a breakeven year for the BBBA with its third-place Buffalos team.19

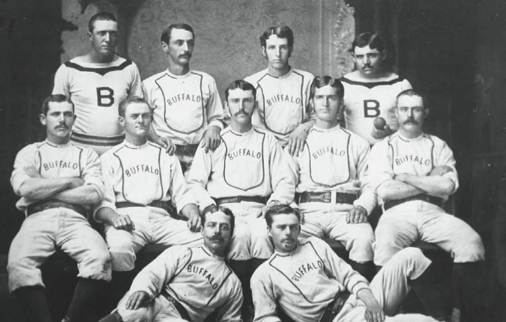

1878 Buffalo Bisons, International League champions. Back row: Tom Dolan, Dick Allen, Bill McGunnigle, Pud Galvin. Middle: Bill Crowley, Dave Eggler, Steve Libby, Chick Fulmer, Denny Mack. Front row: Davy Force, Trick McSorley. (Public Domain)

For the 1882 season, Jewett and Moffat retained their respective positions in the BBBA as president and vice president. Spencer was quietly eased out as secretary, with that position now combined with the treasurer. Hughson now held both offices. This three-man officer lineup remained unchanged into the 1885 season.20

The BBBA engaged in two publicity schemes in 1882 to encourage more Buffalo businessmen to leave their office early to attend an afternoon ballgame. The Buffalo Base Ball Grounds was renamed to be Riverside Park, evoking a pastoral image despite the fact that the ballpark was several blocks away from the Niagara River. The Buffalo press was also encouraged to refer to the team as the Bisons, evoking more cachet than the generic Buffalos. While there had been sporadic references to Bisons in previous years, the nickname gained general acceptance in 1882.21

Discounted admission for women and children was a promotional strategy rolled out late in the season, a novel interpretation of the league’s 50-cent admission requirement for “each adult person.” The BBBA promoted Children’s Day with special admission pricing at the Saturday, September 2, ballgame “when all youngsters under 15 years of age will be admitted for ten cents.” The presumption was that happy youngsters would then encourage adult men in their family to attend future games at full price. The Children’s Day promotion continued the following three Saturdays.22

On September 16, ladies day was added to the 10-cent admission policy on Children’s Day, when 600 women and kids reportedly attended the Bisons game. There was a second ladies day the following Saturday, September 23, when women were admitted for 35 cents. The presumption for adult women was that it would be scandalous for them to sit alone in the grandstand, so they would arrange for a male to escort them and buy a full-price ticket. This was a full nine months before the generally accepted popularization of ladies day by the New York Giants in the summer of 1883, when women were admitted free when accompanied by a gentleman paying full-price admission to the grandstand.23

The 1882 season was the first (and only) time that the BBBA earned a significant operating profit, after three years of needing ad hoc stockholder subscriptions to offset net losses or bolster a breakeven status. Citing a brief summary provided by Hughson, the Buffalo Courier reported that “the receipts for the season were $34,166.63 and the disbursements $27,526.11, leaving a net profit of $6,640.52.” Since the receipts likely included the year-end $2,678 cash on hand of the 1881 financial statement noted above, the true operating profit during 1882 was undoubtedly closer to $3,962, still a sizable result.24

The Jewett-Moffat-Hughson regime seemingly was all in with the National League’s reserve rule to depress player salaries and thus lower ballclub expenses, which no doubt assisted in creating this zenith of BBBA profitability (even though no salary expenditure figures were provided by Hughson). While 1882 was a good year financially for the third-place Bisons, this was the last year the BBBA publicly disseminated any specific financial information.

For the 1883 season, the National League admitted two new ballclubs located in New York City and Philadelphia, the nation’s two largest cities. This was good news for the BBBA, as the additions enhanced the League’s national image and could help attract more patrons to Buffalo ballgames. However, to make room for these two new cities, the League jettisoned the Worcester and Troy clubs (having had the lowest home attendance counts in the League). This was not a good sign for Buffalo’s future, as the Bisons had the sixth-best attendance in 1882, barely above that of Worcester or Troy.25

BBBA management was hamstrung from the outset to try to earn a profit in 1883, because the National League schedule did not contain any holiday home dates for Buffalo. The incoming New York and Philadelphia ballclubs got preferential treatment, receiving home dates for holiday twin bills on both Decoration Day and Independence Day. The lack of the usual big holiday gate on Independence Day was a huge burden for Buffalo to overcome. The expansion of the league schedule to 49 home games in 1883 (seven additional games) was small consolation.26

The BBBA introduced special grandstand-seat pricing for women to attend Buffalo ballgames on a regular basis in 1883, rather than continue the ad hoc promotion of ladies day. “Ladies’ coupon tickets, in packages of five, will be sold for $3,” the Buffalo Commercial Advertiser reported, “but with each package sold will be presented a package of five more, so that in reality the price of ladies’ tickets will be but 30 cents each,” 50 percent off the standard cost of 60 cents for grandstand admission that the women’s expected male companion would pay.27

Children’s Day with its 10-cent admission continued to be a regular event in 1883, with the promotion offered at most Saturday home games at Riverside Park.28

While the Bisons finished in fifth place in the 1883 league standings, Buffalo experienced by far the lowest home attendance of any ballclub in the National League. Hughson, the BBBA treasurer, released no specific numbers for the 1883 season, saying the financial situation was “a little more than self-sustaining, but the net profit was quite insignificant.” This aligns with a detailed estimated calculation published by the Buffalo Express that concluded that operating profit was negligible. The Express estimate carried forward the $6,640 cash on hand at year-end 1882 and contained a similar value at year-end 1883, which very likely mirrored Hughson’s actual BBBA financial statement for 1883.29

The Bisons needed a new ballpark for the 1884 season, since the owner of the land beneath Riverside Park declined to renew the lease. Olympic Park was built on leased land at the corner of Richmond Avenue and Summer Street, several blocks east of Riverside Park. The $6,000 capital expenditure for the new ballpark was a death knell for the BBBA, though, since “a large share of the [club’s] earnings will be expended on the new grounds.” The $6,000 cost to erect Olympic Park approximates the BBBA net profit for the 1882 season, as announced by Hughson, as well as the estimated cash on hand at year-end 1883, both as noted above. The BBBA had little money left as a cash cushion for the 1884 season.30

Jewett, president of the BBBA, apparently expected increased patronage at Bisons ballgames in 1884 following his January inauguration as mayor of Buffalo. However, Jewett was defeated by his Democratic opponent in the mayoral election held in November 1883. He then seemed to lose interest in the Bisons, as Hughson began to attend league meetings and became the primary public spokesman. Hughson acted as the de facto head of the BBBA in 1884 and 1885, much more visible than Jewett.31

In March 1884 Hughson gave the Buffalo Evening News a rundown on the team’s ballplayers, the new Olympic Park, and for the first time publicly a list of stockholders. Hughson noted that the BBBA’s capital stock was $7,000, but only $5,000 had been issued, so that $2,000 was still available for sale (40 shares at $50 per share). Apparently, the 1881 increase in capital stock was hugely unsuccessful, or more likely some shares of the initial 1878 stock issue had been returned to the BBBA (to avoid those pesky stock subscription requests to bail out the club’s net losses). On the list of 45 men that Hughson identified as current BBBA stockholders were several of the original investors, including former BBBA officers Edward B. Smith and John B. Sage, the latter now having secured a contract with the National League to print colorized posters and scorecards for its ballclubs.32

Hughson gave an extensive interview to the Buffalo Commercial Advertiser, describing the new ballpark as well as the ticket policy for the 1884 season (with its expanded 56-home-game schedule). Pricing for women’s and children’s tickets was now institutionalized and there were price increases for male patrons. “Ladies’ coupons will be sold the same as last year, five for $3 with five complimentaries,” which now applied to a special Ladies Stand section of the Olympic Park grandstand that contained armchairs for seating rather than a wooden plank. “The general admission fee per game will be 50 cents for adults [same cost] and 25 cents for minors,” as 10-cent Children’s Day was eliminated. “A grandstand seat will cost 15 cents [increase of 5 cents] and a gentleman may enjoy an arm-chair by his lady for 25 cents.”33

There was nothing Hughson could do about the weather in Buffalo, though, as the scheduled Independence Day twin bill between the Bisons and the Boston club was rained out, eliminating an anticipated $2,500 in revenue. For a second consecutive year, the lack of holiday baseball was a huge deterrent to the BBBA’s overall profitability. Hughson’s lukewarm “satisfied with the season financially” likely indicates another breakeven season for the third-place Bisons, which was the conclusion of one observer. Hughson also noted that he thought it good that the new ballpark was paid for out of retained earnings from previous seasons, and quipped that “stockholders were so used to assessments that they probably considered it a good thing to come out of the [1884] season without any.”34

During the four years from 1881 to 1884, the Buffalo Bisons compiled four winning seasons, but the BBBA had only one truly profitable year (1882), with the other three being essentially breakeven. The National League’s minimum admission charge of 50 cents proved unsuccessful in Buffalo, a city where 25-cent admission arguably could have made the BBBA financially viable. This, however, would have clashed with the League’s desired to see middle-class and upper-income businessmen as patrons.

There were early indications of the forthcoming demise of the Buffalo Bisons ballclub. In October 1884 O’Rourke resigned as player-manager, when he signed with the New York Giants. Hughson named Galvin to replace O’Rourke as team captain on the field, but left the manager position vacant. Hughson handled most of those off-field duties (The expanded reserve rule now included up to 11 players, making player re-signings less onerous. O’Rourke, by his contract, was not subject to that rule.) More ominously, in February 1885 the BBBA directors actively discussed alternatives to baseball at Olympic Park. Proposals included a roller-skating rink, bicycle race track, and lawn tennis courts.35

By July 1885 the BBBA was hemorrhaging money. Spencer Clinton, a club director, told the Buffalo correspondent to Sporting Life that there were “slim prospects of getting out [of the red ink], and the club could certainly be no worse off with new men than with the old.” The BBBA directors looked to reduce expenses by jettisoning its highest-paid ballplayers. Galvin was the first to go, as the BBBA received $1,500 to release him to the Pittsburgh club in the American Association. Presumably, that money was used to reduce the BBBA’s deficit in the current season. The directors then tried to auction off several other players, particularly the Big Four of Brouthers, Richardson, Rowe, and White. However, the Big Four “upset all calculations by refusing to become party to any deal.”36

In mid-September, Jewett administered the coup de grace that would extinguish the life of the BBBA and the Bisons team. He struck a deal with Frederick K. Stearns, president of the Detroit ballclub, to receive $7,000 to release the Big Four to Detroit and for Stearns to operate the depleted Buffalo team for the remaining three weeks of the 1885 season. After paying off the rest of the BBBA’s current financial obligations, the residue of the $7,000 payment was placed in the hands of a trustee for the benefit of BBBA stockholders. Jewett anticipated that this trust would return to stockholders their original purchase price plus a 20 percent dividend.37

The new board of directors of the BBBA consisted of six men from Detroit – Stearns, Charles H. Smith, Joseph A. Marsh, James L. Edson, Edgar O. Durfee, and John B. Maloney – and one man from Buffalo, James Campbell. These directors named Smith as president, Stearns as vice president, and George Hughson as secretary-treasurer, the only holdover from the prior ownership.38

The Buffalo Bisons officially exited the National League at the league meeting in December 1885.39

CHARLIE BEVIS is the author of eight books on baseball history. He is a retired adjunct professor of English at Rivier University in Nashua, New Hampshire.

Notes

1 “Base-Ball Match on Saturday,” Buffalo Express, July 27, 1877; “Base Ball,” Buffalo Express, October 22, 1877; “The Stockholders of the Buffalo Base Ball Association in Council,” Buffalo Express, August 13, 1879.

2 “Base Ball,” Buffalo Express, November 14, 1878. The fiscal year of the Buffalo ballclub was November 1 to October 31. For simplicity, references to financial results in this article are labeled to the baseball season included within the fiscal year.

3 “Sporting News,” Buffalo Commercial Advertiser, November 13, 1878; “Base Ball,” Buffalo Express, November 18, 1878; Peter Morris, ed., Base Ball Pioneers, 1850-1870: The Clubs and Players Who Spread the Sport Nationwide (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2012), 106, 114; Buffalo City Directory, 1879, 560, 590.

4 “Base-Ball: The Buffalos and the League,” Buffalo Commercial Advertiser, November 26, 1878; “The Regular Meeting,” New York Clipper, December 14, 1878.

5 “Base-Ball,” Buffalo Commercial Advertiser, March 8, 1879; Buffalo City Directory, 1879, 53; Spalding’s Official Base Ball Guide, 1879, 111. The Spalding Guide did note that the information was as of February 24, 1879, two weeks before Smith and Sage switched roles. The Buffalo City Directory had the correct information since it was published at a later date.

6 “Base Ball,” Buffalo Commercial Advertiser, June 17, 1879.

7 “Sporting News,” Buffalo Commercial Advertiser, July 5, 1879.

8 “Next Year’s Nine,” Buffalo Express, August 13, 1879.

9 “The League Meeting,” New York Clipper, October 11, 1879; “The Base-Ball Interest,” Buffalo Express, October 2, 1879.

10 “The League Convention,” New York Clipper, December 13, 1879; “The League and Its Fifty-Cent Tariff Discussed,” Buffalo Commercial Advertiser, December 23, 1879.

11 “Stockholders’ Meeting,” Buffalo Courier, October 1, 1879; Buffalo City Directory, 1880, 52; Brian Martin, Pud Galvin: Baseball’s First 300-Game Winner (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2016), 88-89.

12 “Stockholders’ Meeting,” Buffalo Express, September 15, 1880; “Sporting News,” Buffalo Commercial Advertiser, October 5, 1880.

13 “The Rochester Meeting,” New York Clipper, October 16, 1880.

14 “Sporting News,” Buffalo Commercial Advertiser, October 5, 1880; Buffalo City Directory, 1881, 50.

15 Buffalo City Directory, 1883, 449, 457, 562.

16 “Sporting News,” Buffalo Commercial Advertiser, October 5, 1880; Mike Roer, Orator O’Rourke: The Life of a Baseball Radical (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2005), 90-93.

17 “The National Game,” Buffalo Express, January 5, 1881.

18 Charlie Bevis, Doubleheaders: A Major League History (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2011), 19-20, 205; “Twice Beaten,” Buffalo Express, July 5, 1881. Detroit shares this baseball first, as it also conducted a twin bill on the same date.

19 “Financial Statement of the Buffalo Base Ball Association,” Buffalo Commercial Advertiser, December 2, 1881.

20 “Preparing for Base Ball Season,” Buffalo Evening News, March 6, 1882; Buffalo City Directory, 1882, 48; Buffalo City Directory, 1883, 43; Buffalo City Directory, 1884, 73; Buffalo City Directory, 1885, 60.

21 “Sporting,” Buffalo Commercial Advertiser, April 29, 1882; “A Brilliant Game,” Buffalo Express, May 4, 1882; “Base Ball Matters,” Buffalo Express, May 18, 1882.

22 “Sporting Notes,” Buffalo Express, September 2, 1882; “Sporting,” Buffalo Commercial Advertiser, September 16, 1882.

23 “Sporting,” Buffalo Commercial Advertiser, September 16 and 23, 1882; Charlie Bevis, “Ladies’ Day at Boston Red Sox Games: How Discounted Admission for Women Impacted Game Schedules,” NINE: A Journal of Baseball History & Culture, Fall-Spring 2021-22: 114.

24 “Brief Mention,” Buffalo Express, December 20, 1882. Beyond a breakdown of the gate receipts by home and road games, Hughson provided no additional detail.

25 Robert Tiemann, “Major League Attendance,” in Total Baseball: The Official Encyclopedia of Major League Baseball (Kingston, New York: Total Sports Publishing, 2001), 74.

26 Bevis, Doubleheaders, 22.

27 “Sporting News,” Buffalo Commercial Advertiser, March 28, 1883.

28 “Children’s Day Next Saturday,” Buffalo Evening News, May 17, 1883; “Sporting News,” Buffalo Evening News, July 14, 1883.

29 “Notes and Comments,” Sporting Life, February 20, 1884; Tiemann, “Major League Attendance,” 74; “A Statement Furnished for the Benefit of Stockholders in the Buffalo Base Ball Club,” Buffalo Express, October 29, 1883. The figures are very fuzzy and difficult to read in the digital version of the Express article, creating an unreadable final cash-on-hand number.

30 “The Buffalo Club,” Sporting Life, October 15, 1883.

31 “Mayor Scoville,” Buffalo Evening News, November 7, 1883.

32 “The Buffalos for 1884,” Buffalo Evening News, March 3, 1884; John Thorn, “Who Was John B. Sage? A Forgotten Titan of Buffalo Baseball,” Our Game (mlblogs.com).

33 “Olympic Park,” Buffalo Commercial Advertiser, March 8, 1884; “The Buffalo Club,” Sporting Life, October 15, 1883.

34 “From Buffalo,” Sporting Life, November 26, 1884; “The Financial Part of It,” Sporting Life, October 22, 1884; “Buffalos for 1885,” Buffalo Times, February 23, 1885.

35 “A Buffalo View,” Sporting Life, December 17, 1884; “Sporting News,” Buffalo Commercial Advertiser, February 27, 1885.

36 “The Bisons: They Will Stick,” Sporting Life, July 22, 1885. The sale of a player to another ballclub in 1885 was a complicated logistical process, not the simple contract transfer of today. Such transactions then actually happened in reverse of today’s sale process – the player first agreed to terms with the buying club, then the selling club released him after receiving the negotiated payment from the buying club. Otherwise, a released player could sign with any club he wished.

37 “The Franchise Sold: The Buffalo Base Ball Club Bought by the Detroit Managers,” Buffalo Commercial Advertiser, September 17, 1885; “A Stunner: Bisons Sell Out,” Sporting Life, September 23, 1885.

38 “Finale of the Buffalo Baseball Club,” Buffalo Express, September 19, 1885; “A Base Ball Muddle,” Buffalo Sunday Morning News, September 20, 1885.

39 “The League Convention,” New York Clipper, November 28, 1885.