Los Angeles/Brooklyn Dodgers team ownership history

This article was written by Andy McCue

This article was published in the Team Ownership History Project

From its beginnings in the 1880s, the franchise now known as the Los Angeles Dodgers has provided a parade of well-known players and managers, 23 pennant winners, and six World Series victories. Off the field, it has been associated with some of the most recognized front-office talent in the game’s history. Names such as Charles Byrne, Charles Ebbets, Larry MacPhail, Branch Rickey, Buzzie Bavasi, and Walter O’Malley have been posted on Dodger offices.

Yet, the standard works on the team are riddled with mistakes and misconceptions about who really owned the team as opposed to who ran it. For, in over 130 seasons, only once has one man owned the Dodgers completely, and then for only about 4½ years.

Born in Brooklyn — Ferdinand Abell, Joseph Doyle et al.

The Dodgers began modestly, and in Manhattan. In the fall of 1882, George Taylor’s doctor had suggested he find a less stressful line of work. The 30-year-old Taylor was night city editor at the New York Herald.1 A baseball fan, Taylor decided he’d like to try his hand at running a team and he felt the New York area was ripe for one.

There hadn’t been a major league baseball team in New York since 1876, when the city’s entry had been kicked out of the National League for refusing to complete its schedule with a Western road trip. Six seasons later, the National League was looking to get back into the country’s premier city. And the National League had been so successful that another group of entrepreneurs was considering a second major league, to be called the American Association. The Association also wanted a franchise in New York, giving Taylor two opportunities. Taylor’s eyes focused on Brooklyn, where real estate for a ballpark was less expensive than in Manhattan.

Taylor’s initial plans hit the rocks when his unidentified financial angel backed out, leaving Taylor with only a lease on some open land just east of the Gowanus Canal. Taylor spoke to an attorney, John Brice, and Brice mentioned Taylor’s plans to a 39-year-old real-estate agent named Charles H. Byrne, who shared Brice’s office.2

Byrne’s brother-in-law was Joseph J. Doyle, and the two men were partners in a gambling house on Ann Street in Manhattan.3 After investing $12,000 in equipping the team and grading the Gowanus ballpark site, Doyle paled at the cost of erecting a grandstand.4 He told Byrne to go ahead worrying about how to spend the money while he raised it. Doyle’s gambling connections led him to the man who would be the franchise’s financial mainstay for two decades.

Ferdinand A. Abell came from one of the older and more established families in the country. His uncle had founded the Baltimore Sun, which was then being run by Abell’s first cousin. Abell himself ran a casino in the fashionable Newport, Rhode Island, area, a casino frequented by Vanderbilts. He had other business interests throughout the Northeast.5 When the team took out its incorporation papers in March of 1883, Abell’s name was listed first among the partners, although Byrne was the president of the team.6

The ownership breakdown within the group is fuzzy. Neither The Sporting News nor Sporting Life existed while the team was being organized. Most of what is known about ownership during this period comes from interviews done decades later and with at times conflicting details. In retrospect, it seems clear Abell and Doyle kicked in most of the money, Byrne a small amount of money and Taylor the lease. But Byrne, the team’s president, and Taylor, its manager, were the men in the public eye and Abell’s importance was not clear to the public for almost a decade.

While Taylor was trying to round up financial backers, the National League and the American Association had found their New York connections. Byrne’s group settled on joining the Interstate Association, a minor league operating mostly in New Jersey and Pennsylvania, and began play May 1, 1883. Their home debut was delayed until May 12 while they waited for the grandstand at what they called Washington Park to be completed. It was at the southern corner of 3rd Street and 4th Avenue near the Gowanus Canal in the Brooklyn neighborhood known as Red Hook. It was a working-class Irish neighborhood, well served by trolley and street-car lines.7

As president, Byrne performed all the jobs a team’s front-office staff would do today. He supervised tickets, concessions, ballpark acquisition and maintenance, sometimes delegating duties to a young employee named Charles Ebbets who joined the club the day of its first game at Washington Park. In addition, Byrne had significant input on trades and purchases, a job he shared with the team’s manager.

Byrne was a small man, a Napoleon to his admirers. Sporting Life described him as “a nervous little man, full of life and grit, a good talker, very earnest and aggressive…” Byrne was to grow into one of the most influential voices in the American Association and, later, the National League.8

But for the moment, he was leading a team that was going nowhere in the Interstate Association. Then, in July, the league-leading Merritts of Camden, New Jersey, folded. Byrne snapped up five of their best players and the Dodgers surged to the pennant. Flushed with this success, Byrne talked his way into the American Association for the 1884 season.

In the Association, Byrne’s team was clearly outclassed, falling to ninth place in a 13-team league in 1884. Byrne realized that to compete at this higher level, he would need to be aggressive about acquiring better, and presumably more expensive, players. Taylor was replaced as manager before the 1885 season, and left the partnership around the same time.9 Abell and his money took a more prominent role in the team. Byrne scooped several players out of the National League’s Cleveland franchise when it collapsed. He picked up more from the American Association’s original New York Mets when that team disbanded after the 1887 season. By 1889, Byrne’s strengthened team won the American Association.

In 1890 Byrne moved the Dodgers into the National League and into a highly competitive race of attendance. The New York metropolis boasted five major-league teams in 1890. The new Players League, grown out of the Brotherhood of Professional Base Ball Players, had created franchises in both Brooklyn and Manhattan. And the American Association had cobbled together a Brooklyn team to replace the Dodgers.

Adding the Players League Magnates

While other National League magnates refused to match Players League salary offers, Byrne paid. It was to be his salvation. With the 1889 American Association pennant-winning lineup virtually intact, Brooklyn swept to the National League flag in 1890, edging Chicago by six games. The victory enabled the team to lose less money, $25,000, than any of the other New York teams.10 It also left Byrne’s group in a strong negotiating position when the Players League magnates began to sell out the Brotherhood that winter.

Chauncey and his fellow Brooklyn Brotherhood owners had more ready cash, but that was their only asset. Byrne’s group had the franchise in the more stable league, the better players and the better prospects.

Eventually, a deal was cut. The Chauncey group agreed to pay Abell, Byrne, and Doyle $30,000 in cash and to give them another $10,000 out of future profits. This implied a value for the franchise of approximately $80,000, although it now was capitalized at $250,000. A new corporation was created, with Abell, Byrne, and Doyle controlling 50.4 percent of the shares initially. Byrne remained as president and three of the five directors slots went to this triumvirate. Chauncey’s group got the other two seats on the board and the remainder of the stock. In addition, Chauncey won the transfer of the Dodgers to Eastern Park on land he owned in the East New York section of Brooklyn, land served by trolley lines in which other members of the Chauncey group owned interests.11

As if setting a pattern for Dodgers ownership for the next quarter-century, the Players League group didn’t fulfill its part of the merger agreement. They paid only $22,000 of the $30,000 cash, and then began ceding stock to Abell and Byrne.12 When baseball profits weren’t forthcoming in subsequent years, they ceded more stock to Abell rather than come up with the unpaid balance. Over the next few years, several smaller members of the Players League group would sell out to Abell.

Abell’s dominance was also cemented by the withdrawal of Doyle from the partnership. Doyle’s previously close relationship with Abell had deteriorated over the years. Ebbets said Doyle was frustrated by the poor attendance caused by Eastern Park’s location even though the Dodgers were the reigning National League champions. Doyle wanted out and came up with an offer from two men The Sporting News identified only by their last names, Marx and Jolly, and their occupation, gamblers.13

Abell the casino operator said he was dismayed at the idea of gambling men coming into baseball. More believably, he also was reported to be worried that Doyle would persuade his highly esteemed brother-in-law, Byrne, to go with him and start another American Association team in Brooklyn. Abell persuaded Doyle to sell out to him in January 1892. Byrne also sold some shares to Abell during the early 1890s.

These years perhaps also saw the first appearance of the name Charles Ebbets on the rolls of the franchise’s owners. Chauncey reportedly took a shine to Ebbets and sold him a small piece of his own shares.14 It must have been a very small piece. By the mid-1890s, Abell told a reporter, he owned 51 percent of the team, Byrne 12 percent, and the Chauncey group 37 percent.15

The Gay Nineties weren’t for the Brooklyn team. Attendance, which had hit 353,690 in 1889, averaged 184,000 during the 1890s.16 Ebbets in later years made it clear he thought the major problem was the location. East New York was just too far for most people. The mediocre quality of the team didn’t help much either.

The team lost money virtually every year. Appeals were made to the shareholders to make up the deficits, but only Abell responded. Ebbets called him “the human war chest.”17 The Rhode Island financier slowly hiked his share of the team. It wasn’t as if he wanted to. Abell had a standing offer to his partners that he would either buy them out or sell to them, but only a few of the smaller investors took up his offer, and then only to sell out.18 By 1897, Abell said, he had lost $100,000 on his investment in the team.19 Almost all of the losses had occurred beginning with the Players League competition, but he had lost $25,000 in the 1896 and 1897 seasons alone.20

Abell is a somewhat vague figure. Reporters of the period loved to call him Chesterfieldian, a term that conveyed upper-class English regard for manners, rectitude, and a gallant attitude toward women. The source of most of his wealth was referred to coyly. Ebbets skated around it by saying that when Abell joined team ownership he “knew a great deal about some sports, but nothing whatever about baseball.” He developed a reputation of being hard to deal with, but Ebbets said that once you knew his ways, you could get yours.21

The Emergence of Charles Ebbets

Charles Ebbets was taking a larger role in Brooklyn management. Born in Manhattan’s Greenwich Village on October 29, 1859, of an old Dutch family, Ebbets was the son of a bank president and an associate of Alexander Cartwright, whose Knickerbocker Baseball Club had played an important role in codifying baseball’s early rules.22 Charles had left school early, joining an architectural firm where he worked as a draftsman on the Metropolitan Hotel and Niblo’s Garden, a famous amusement center. He later went to work for publishing houses, selling cheap fiction and keeping the books. All these skills were to stand him in good stead when he ran the Dodgers.23 At first Ebbets was a bookkeeper but he pitched in doing whatever Byrne needed. Soon, Byrne was delegating substantial tasks.

Charles Ebbets was taking a larger role in Brooklyn management. Born in Manhattan’s Greenwich Village on October 29, 1859, of an old Dutch family, Ebbets was the son of a bank president and an associate of Alexander Cartwright, whose Knickerbocker Baseball Club had played an important role in codifying baseball’s early rules.22 Charles had left school early, joining an architectural firm where he worked as a draftsman on the Metropolitan Hotel and Niblo’s Garden, a famous amusement center. He later went to work for publishing houses, selling cheap fiction and keeping the books. All these skills were to stand him in good stead when he ran the Dodgers.23 At first Ebbets was a bookkeeper but he pitched in doing whatever Byrne needed. Soon, Byrne was delegating substantial tasks.

Ebbets was a marketing campaign all by himself. He was a joiner, founding the Old Nassau Athletic Club among others. He was active in the Masons, bicycling and Democratic Party politics. He participated in at least four bowling clubs and many secret societies. He had been elected a state Assemblyman and a city alderman and lost an 1897 race for city councilman by literally the narrowest of margins, 23,183 votes to 23,182. He also lost a 1904 race for the state Senate when Democrats were buried in the Theodore Roosevelt landslide.

With the Dodgers’ losses mounting in late 1897, Ebbets made his move. He arranged to borrow money to buy the Chauncey group’s shares. The reported purchase price of $25,000 implied a value of around $70,000 for the whole team.24 Ebbets then secured an option on Abell’s shares. On January 1, 1898, he invited the reporters who covered the Brooklyn team to a dinner and announced that he now controlled 85 percent of the team. The remaining shares were owned by Byrne, who was on his deathbed. Three days later, on January 4, the man who had run the team since it was founded 15 years before died.

The results for Ebbets were mixed. On the positive side, he quickly assumed Byrne’s role. With Abell’s backing, he was elected president. He would exercise control over the team until his own death in 1925, while his stable of financial backers and partners changed several times.

But Ebbets didn’t gain ownership. He didn’t come anywhere near it. His option to buy Abell’s controlling shares ran out February 1 and Ebbets conceded he hadn’t been able to raise the money to exercise it. Abell decided not to sell out to anyone else and continued to invest in the team.25 What happened to Ebbets’ purchase of the Chauncey shares isn’t clear, but by the next winter Ebbets owned only 18 percent of the team, although Chauncey would later claim he’d been paid in full and on time.26 Presumably Abell picked up some of these shares as well.27

However, Ebbets’ management was already bearing fruit. He moved the team back from Eastern Park to a location diagonally across the corner from the old Washington Park. It was a location much more convenient for fans. Ebbets’ problem was finding $25,000 to build a new ballpark. He’d hocked himself to buy out the old Players’ League magnates and Abell was reluctant to sink any more money.

Ebbets’ white knights were trolley-car magnates, including Al Johnson, once president of the Players League. Johnson’s Nassau Railroad and the Brooklyn Heights Railroad companies bought the site, graded it, and built what became known as the New Washington Park for about $15,000. In addition, they agreed to charge only $5,000 in annual rent, $2,500 less than the team had paid in Eastern Park.28

But Ebbets also needed a better club than the one that finished a dismal 10th in 1898. He saw the potential for what was called syndicate baseball. Essentially, syndicate ownership was control of more than one team by one management group. The owners would then move all the best players to the team in the better market, leaving the other team to languish.

Perhaps Ebbets realized its potential because Abell was looking at other ways to cut his losses. One New York newspaper reported that Abell was in talks with Cleveland owners Stanley and Frank Robison, and also with streetcar magnate Albert Johnson. Importing players from Cleveland and $20,000 from Johnson would leave a Brooklyn franchise split among Abell (50 percent), the Robisons (30 percent), and Johnson (20 percent). Ebbets would have been cut out and the Brooklyn Eagle suggested that there was no substance to the rumor.29 The Robisons eventually struck a syndicate deal with the team now known as the St. Louis Cardinals.

Looking elsewhere, Ebbets and Abell got in touch with Harry Von der Horst. Von der Horst was a Baltimore brewer who had owned the Orioles since they had been in the American Association with Byrne’s teams. But even in the early and mid-1890s, when the Orioles were winning National League pennants and establishing a reputation as a cradle of managers and one of the great teams of all time, they hadn’t made much money.

Ebbets and Von der Horst decided they could put Baltimore’s better players — Wee Willie Keeler, Joe Kelley, Joe McGinnity, and Dan McGann for example — with Brooklyn’s population of fans and come up with a winner on and off the field. In early 1899, the two camps struck a deal to split ownership of both franchises. Baltimore manager Ned Hanlon would come to Brooklyn as manager and part-owner. Ebbets would remain as team president. Von der Horst and Hanlon would own 50 percent, as would Abell and Ebbets. Ebbets’ share was variously reported as 9 percent and 10 percent. Hanlon’s was 10 percent.30

The deal was an initial success in Brooklyn. The team won the 1899 National League race and drew 269,641 fans, 120 percent more than a year before. They won again in 1900, although attendance slumped to about 183,000 and Ebbets had to fend off rumors that the team would be moved to Washington.31 Then the team fell on harder times. Brooklyn lost stars such as Keeler and McGinnity to the new American League, which had proclaimed itself a major league in 1901. Attendance fell. Ebbets’ partners were skittish.

Von der Horst had become unhappy with Hanlon for reasons that remain obscure. His confidant on the team was now Ebbets. Early in 1905, Ebbets was able to persuade an ailing Von der Horst to sell him virtually all of his shares. Ebbets newest financial angel was an old friend, Brooklyn furniture manufacturer Henry W. Medicus.32 The two had been extremely active in Brooklyn bowling circles for years. Medicus was elected an officer of the team and kept some shares in his name, but he was willing to remain even further in the background than Von der Horst.33 This gave Ebbets effective control of the team, although his personal holdings were well under 50 percent.34

By the end of 1906, Von der Horst had died and Hanlon had signed to manage the Cincinnati Reds. It wasn’t until November of 1907 that Ebbets got rid of Hanlon completely. At that time, he and Medicus bought out Abell, Hanlon, and the tiny holding of Von der Horst’s estate. Ebbets announced that he controlled 70 percent of the team, including 10 percent owned by Charles Ebbets Jr., while Medicus had the rest. Medicus again provided most of the cash, although the shares were in Ebbets’ name.35 The transaction didn’t go smoothly. Abell and Hanlon had deferred payment for some of their shares and had to sue Ebbets to get their money back.36 It was later reported that Medicus had paid $30,000 for his shares, putting the franchise value at around $100,000.37

The team entered a period of relative prosperity. Attendance was steady (averaging about 238,000 over the decade of the 1900s), and even if the team wasn’t performing very well on the field, it was apparently providing modest profits. In 1909, at a postseason banquet, the long-winded Ebbets reviewed the history of baseball and concluded that the sport was still in its infancy. The audience dissolved in catcalls and Ebbets was nearly heckled off the stage. But he believed what he said, and was emboldened to try his most enduring venture.

The general prosperity led Ebbets and other major-league owners to deal with one of their most persistent problems — the quality of their facilities. Wooden grandstands were cheap to erect, but they crumbled, collapsed, and burned. (A fire that destroyed the old Washington Park grandstand in May 1889 had occasioned the first appearance in the New York Times of the name Charles Ebbets, misspelled Ebbitts).38

The second Washington Park was a wooden firetrap in an often smoky industrial area near the malodorous Gowanus Canal. Ebbets had added so many seats that he’d severely restricted foul territory. Its main advantage was its central location, but Brooklyn’s center was moving south and east. Ebbets had to choose his site carefully. He had put much of the blame for the Dodgers’ bad decade in the 1890s on their move to Eastern Park — too far from the center of downtown Brooklyn. But now it was almost 20 years later and the city had grown enormously. The 1890 census, taken the year the Dodgers won their first National League pennant, showed 806,343 people in the city of Brooklyn. By the time of their sixth place finish in 1910, there were 1,634,351 people in the borough of Brooklyn.39

Over a dozen years, Ebbets bought up plots of land in an area known as Pigtown It was relatively cheap because of its population of squatters, but it was also along the path of rapid growth. His site, as Ebbets noted excitedly in a letter to August Herrmann, chairman of the National Commission, the three-man body that oversaw baseball before the commissioner system, was served by nine mass-transit lines. “Between 3,000,000 and 4,000,000 people can reach the new site by surface, subway or elevated in thirty to forty five minutes,” Ebbets wrote. It was within easy reach of the older neighborhoods but poised to be in the middle of the borough’s future expansion.40

In January 1912 Ebbets announced that he had put together the parcel and intended the Dodgers to have a modern ballpark on the site. Asked what he would call it, Ebbets said he didn’t know, but the reporters began calling it Ebbets Field. Modest Charlie didn’t object. The new stadium was a focus of civic pride for Brooklyn. In a magazine article, Ebbets crowed that his stadium would fill “all demands upon it for the next thirty years.”41 Just to show he was on the cutting edge, he planned a parking garage capable of holding a few hundred automobiles or carriages.42

Enter the McKeever Brothers

Ebbets began construction in March 1912. His public cost estimate was $750,000 including land.43 But in his letter to Herrmann, he gave a construction budget of about $325,000 plus almost $200,000 for the land, $100,000 of which had already been paid. He estimated that the money would be raised from a bond sale of $275,000, a bank loan for $100,000 that he would secure personally, and the team’s $50,000 profit from 1912. He was probably closer with the public estimate.

The 18,000-seat ballpark was supposed to be finished by June, or maybe August, 1912.44 It wasn’t. Excuses were given about undelivered materials and labor troubles. Apparently, though, the real trouble was money. Ebbets really hadn’t put together a realistic financial plan. In late August he announced that he had bought out Medicus and taken new partners. They were two politically-connected brothers, Ed and Steve McKeever, who were in the construction business.45 Ebbets wouldn’t say how big the brothers’ stake was, but subsequent events proved that they each had received 25 percent for their investment. The breakdown of stock blocs created by this transaction was to persist for almost 50 years.

The brothers McKeever had textbook careers on how the nineteenth-century Irish got ahead. Steve was born in 1854 and Ed in 1859, both in Brooklyn, sons of a cobbler. Both received minimal education, Steve’s being interrupted when he ran away in an unsuccessful attempt to join the Union Army as a Civil War drummer boy. He went to work as a horse boy for a trolley line near the Fulton Street Ferry and was eventually apprenticed to a plumber. One of Steve’s first contracts was for plumbing work on the Brooklyn Bridge. Ed also left school at 14, first working for a brass wholesaler and then joining with Michael J. Daly to form the Hudson River Broken Stone Company.46

Within a few years, the brothers combined their expertise in plumbing and stonework to form the E.J. & S.W. McKeever Contracting Company. They had also learned well from Daly, who got government contracts through his excellent (Republican) political contacts. When Steve McKeever married in 1892, one of his ushers was Hugh McLaughlin, boss of the Brooklyn Democratic Party. The McKeevers built their company with lucrative government contracts to install sewers and water mains and pave streets. Steve, the more gregarious of the two, was a former city alderman. Ed was more the businessman. With New York’s growth, filling government construction contracts was an excellent business. In the early twentieth century, the brothers moved into homebuilding. And they had a lucrative city contract to take Brooklyn’s garbage out to sea and dump it. When the McKeevers’ identity was revealed, sportswriters outdid one another suggesting which of the Dodgers should be given one-way rides on the brothers’ fleet of scows.47 The sale of the garbage contract, for over $1 million, provided the brothers with the cash to buy into the Dodgers.

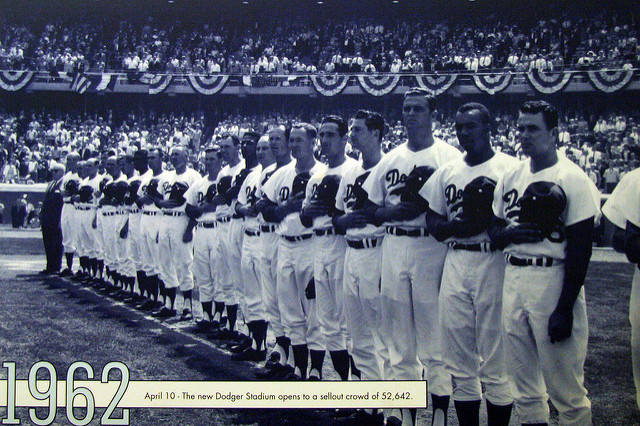

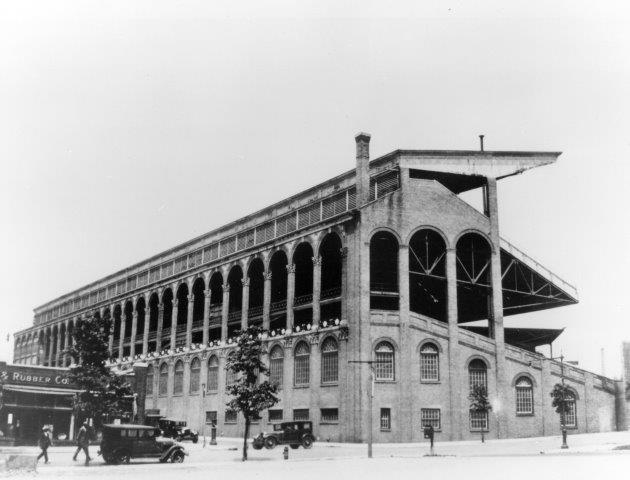

Ebbets Field, circa 1920s. (National Baseball Hall of Fame Library)

How much the brothers paid for their shares isn’t clear. Most of the contemporary sources say $100,000, but The Sporting News obituary of Steve McKeever said it was $250,000 and Robert Creamer’s biography of Casey Stengel lists it as $500,000.48 The Ebbets heirs said Ebbets had borrowed $150,000 from the McKeevers and pledged 50 percent of the stock as collateral.49 When the cost of building the stadium caused him to miss payments, they took over the stock and turned some of their construction expertise to finishing the new stadium on time and at less cost.

The stadium was done in time for the 1913 season. Attendance rose 43 percent to 347,000. With more income and the McKeevers’ bankroll behind him, Ebbets brought Wilbert Robinson in as manager and began to invest in ballplayers. Casey Stengel arrived during the last year in Washington Park, joining Zack Wheat. In the next couple of years, Ebbets, Robinson, and scout Larry Sutton added Jeff Pfeffer, Larry Cheney, Sherry Smith, and Rube Marquard, the nucleus of the pitching staff that would win the 1916 pennant.

The pennant-winning season portended a prosperous era, which would leave Charles Ebbets with an estate worth over $1 million. The improvement started with the quality of the team. A second pennant was added in 1920 and an unexpectedly fine team in 1924 led to a tight pennant race and another attendance record. It was helped by the new ballpark, which was expanded to 22,000 seats for the 1917 season.

The second boost was the collapse of the Federal League after the 1915 season. The Federal League lasted two years and had little success either on or off the field. Ebbets had to compete with a Federal League franchise in Brooklyn, but did so successfully at the gate. He even managed a $30,000 profit in 1914 despite attendance falling by two-thirds, while the Brooklyn Federals lost $800,000 in 1915.50 But, he also had to compete with the Feds on salaries. In 1916 many of those salaries persisted because of multiyear contracts granted to tie up the better players.

The most important factor that helped Ebbets was the final victory of Sunday baseball. In New York state, the ban on Sunday baseball was generally an upstate, rural, Republican, Protestant imposition on a metropolitan, Democratic, Catholic city. Nationally, it was a battle that had gone on for 30 years, with New York one of the last holdouts. In a day when many working people still labored six days a week, the ability to stage a game on their day off was a tremendous shot in the arm for attendance. Sunday baseball was finally legalized in 1919.51 Beginning that year, Ebbets Field attendance would never again fall below the 300,000 Ebbets estimated he needed to break even.

The fourth factor was sheer population growth. By 1920 Brooklyn’s population had hit 2 million, an increase of 23 percent for the decade. By 1930 Brooklyn had passed Manhattan as the city’s most populous borough. The South and East Brooklyn communities — Flatbush, Borough Park, Brownsville, Gravesend, Bensonhurst, New Lots, Bay Ridge, Brighton Beach — were leading the way. Perhaps more important, the percentage of foreign-born Brooklynites had peaked at the 1910 census. The children of the immigrants were a growing percentage of the population and were starting to turn to baseball as part of their pledge of allegiance to their country. In the pennant-winning year of 1916, the Dodgers had drawn more than their share of National League fans for the first time since 1901. They wouldn’t do it again until Sunday baseball arrived in 1919 but then did it every year but two until Walter O’Malley uprooted the team.

Ebbets’ Death and Ownership Deadlocks

Ebbets died near the peak of his success as an owner. He fell ill early in 1925 and died of heart failure in April in the suite at the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel that he now could afford. His funeral was held on a raw day and when the cortege got to Green-Wood Cemetery, it was discovered that the grave had been dug too small for the oversized casket. The funeral party, including Ed McKeever, stood in the rain for an hour while gravediggers widened the muddy hole. McKeever caught a cold, which turned into pneumonia and killed him only 11 days later.

The team’s ownership was thrown into turmoil and a pattern was set that was to last for 13 years. The Ebbets heirs and the McKeever interests fell to feuding and with ownership split equally, decisions were often deferred rather than made. Management was weak, and when the Depression hit, the losses mounted, putting the team effectively under the control of its lenders.

Even with their fans, who were more vociferous than numerous, the Dodgers had fallen on exceedingly hard times by the end of the 1937 season. Phone service had been cut off because the bills weren’t being paid. The team’s office was crowded with process servers seeking payment.52 Ebbets Field was a mass of broken seats, begging for a paint job. Charles Ebbets’ pride, the beautiful rotunda, was covered with mildew.53 The heirs had borrowed heavily against the value of their Dodgers stock, and the stock was worth less and less.

The Brooklyn Trust Co. was the team’s bank, and also served as trustee of the Ebbets and Ed McKeever estates. Its president was George V. McLaughlin. By late 1937 the Dodgers owed $700,000 to the bank, $470,000 on a refinanced mortgage for Ebbets Field.54 It had lost $129,140 in 1937 and hadn’t turned a profit since 1930.55 New York bank examiners were pressuring McLaughlin about overdue loans to the team.56 National League President Ford Frick was threatening to take the franchise back for unpaid bills.57

The board remained divided. McLaughlin, anxious to get repaid, cut off any future advances to the team unless the board found a strong executive. Thrashing around for a solution, Jim Mulvey, husband of Steve McKeever’s daughter and heir, Dearie, approached Frick. He thought Cardinals vice president Branch Rickey might be interested. Rickey said no, but suggested he might have someone who wanted the job, Leland Stanford “Larry” MacPhail. McLaughlin consulted Frick and got the go-ahead.58

The board remained divided. McLaughlin, anxious to get repaid, cut off any future advances to the team unless the board found a strong executive. Thrashing around for a solution, Jim Mulvey, husband of Steve McKeever’s daughter and heir, Dearie, approached Frick. He thought Cardinals vice president Branch Rickey might be interested. Rickey said no, but suggested he might have someone who wanted the job, Leland Stanford “Larry” MacPhail. McLaughlin consulted Frick and got the go-ahead.58

When he came to Brooklyn, the 47-year-old MacPhail carried a large and speckled reputation.59 In Columbus, Ohio, after World War I, MacPhail was refereeing college football games while moving from glass manufacturing to car sales to construction. He was making money but remained restless. He formed a group to buy the minor-league team in Columbus after the 1930 season. He ran the team for three seasons, making it profitable and selling it to the Cardinals as a farm club. He had impressed Rickey despite a clash that got MacPhail fired. In late 1933, when the National League was casting around for someone to run the struggling Cincinnati Reds for the team’s bankers, Rickey had suggested MacPhail.

In three years with the Reds, MacPhail turned the team into a profitable franchise. He was one of the game’s first marketing innovators, from such seemingly obvious things as keeping the ballpark nicely painted and the seats in good repair to touches such as spiffy uniforms for ushers and pretty young women wandering the stands selling cigarettes. There were fireworks and bands.

But MacPhail also broke new ground. He greatly expanded the reach of the Reds’ radio network. Not the least of the reasons for radio’s success in Cincinnati was MacPhail’s use of a young announcer from Florida named Walter “Red” Barber. His most spectacular promotion was night baseball. While night games had been used in exhibitions as far back as 1883, they had gained wide acceptance only with the Depression, when they proved the savior of many minor-league teams. Still, nobody had done it in the majors until MacPhail’s Reds hosted the league doormat Phillies on the night of May 24, 1935, in front of 20,422 fans. With the team itself, he added farm clubs and built the nucleus of the clubs that would win pennants in 1939 and 1940.

But he also wore out his welcome. “There is no question in my mind but that Larry MacPhail was a genius,” said Leo Durocher, who managed the Dodgers for him. But “there is that thin line between genius and insanity, and in Larry’s case it was sometimes so thin you could see him drifting back and forth.” MacPhail was an abrasive man whose abrasiveness was made worse by a drinking problem. “Cold sober he was brilliant. One drink and he was even more brilliant. Two drinks — that’s another story,” said Durocher.60 He would look for scapegoats on his staff, get into fights with one and all and offend many. By the end of the 1936 season, Cincinnati owner Powel Crosley had had enough and MacPhail spent 1937 with a family business in Michigan.

As the 1938 season loomed, MacPhail began the first steps toward creating the solid franchise the Dodgers are today. Some of those changes were cosmetic, but others were fundamental. The cosmetics began with $200,000 McLaughlin had agreed to provide before MacPhail would take the job. Ebbets Field, a monument to peeling paint and mildew, was cleaned and painted turquoise. Its many broken seats were repaired. The infamous corps of usher/thugs was weeded out and retrained. The baseball moves began with his new manager, a loud-mouthed, light-hitting, clotheshorse who was playing shortstop for the team. Leo Durocher was one of MacPhail’s noncosmetic moves. Another was using an additional $50,000 from McLaughlin to buy first baseman Dolf Camilli from the even more hapless Phillies.

MacPhail began to spend money on other players. With Durocher as manager in 1939, the team moved into a competitive third-place finish and the fans started to come back. He scheduled Brooklyn’s first night game, and was rewarded when the fates tossed up Cincinnati left-hander Johnny Vander Meer as the opposing pitcher. Vander Meer’s last outing had been a no-hitter, and under the lights that night, he became the only major-league pitcher ever to throw consecutive no-hitters.

MacPhail also broke the gentleman’s agreement among New York teams not to broadcast their games on the radio. He imported Barber from Cincinnati and locked up a powerful channel and a strong sponsor before the Yankees or the Giants moved. It took Brooklyn fans a while to get used to Barber’s Southernisms such as the catbird seat and the rhubarb patch, but once they did, he became a valuable tool for building interest in the improving product on the field.

With the ballpark fixed up, the team improving, and the Depression finally being dispersed by the onset of World War II, the results quickly showed at the box office and in the team’s books. Attendance was up 37 percent in 1938, despite a drop in the standings from sixth to seventh place. In 1940 the Dodgers led the National League in attendance for the first time. The next year, with a pennant-winning team, attendance hit a franchise-record 1.2 million.

After the team’s steep losses from 1931 through 1937, MacPhail cut the loss to a paltry $3,751 in 1938 and began making profits the next year. And all that financial improvement came despite MacPhail’s buying ballplayers left and right. The club owed Brooklyn Trust $230,000 when MacPhail arrived, with another $470,000 owed on the Ebbets Field mortgage. Spending money on players and paint, he ran the club’s debt to $501,000 by early 1939. By mid-July 1941, the deficit was gone as attendance turned into profits.61 The mortgage remained, but was down to $300,000 and the team had $300,000 in the bank, MacPhail told reporters.62 The team’s bookkeeper would tell MacPhail’s replacement that there was $143,768.99 in the bank and $358,000 still owed on the mortgage.63

That wasn’t as much money as the board thought there should be, however. When Mulvey had sought Rickey’s advice on hiring MacPhail, Rickey had warned that MacPhail would not pay the heirs dividends. And MacPhail’s whole record was a long rap sheet of welcomes worn out. The erratic behavior and drinking eventually overcame extraordinary performance. Despite the profits, the Ebbets and Ed McKeever estates and the Mulveys hadn’t received a dividend since 1932.64 And they’d begun to hear stories. MacPhail was known to dip into the cash drawer before going to the race track.65 They were outraged when, in August 1942, MacPhail called the whole team to a meeting, included all the newspaper reporters, and then predicted that the Dodgers would lose the pennant race, where they had taken an eight-game lead.66 That he was right only made it worse.

A state banking examiner ordered McLaughlin to find out “what the hell is going on with the Dodgers’ books.” McLaughlin’s investigator found that the team was grossing somewhere between $2.5 million and $4 million, but that not all of it was making its way to the bank.67 This had to be stopped.

Whether MacPhail quit or was fired is a matter of dispute. MacPhail said he’d been talking about going back into the Army beginning in March 1942. The Sporting News printed a rumor to that effect in August. Then MacPhail reportedly irritated the board yet again by disobeying specific orders and paying $40,000 for pitcher Bobo Newsom.68 In September MacPhail announced he was going into the Army.

Mulvey turned once again to Branch Rickey.

Wesley Branch Rickey

Wesley Branch Rickey had been born on November 20, 1881, in Scioto County, Ohio, to a poor farming family. He finished grade school, but then farm labor called. With help from a sympathetic retired educator, he read as widely as the resources of Scioto County allowed in the 1890s. He educated himself enough to become the teacher at the local grade school, saving money for college. Eventually, he went off to Ohio Wesleyan University. For the next decade, Rickey’s life was a welter of sporadic academics, sports, and, eventually coaching. He played baseball and football at Ohio Wesleyan and realized he could make money to pay for his studies. He spent part of several seasons in the majors, getting himself a reputation as a marginal catcher, a poor hitter, and an odd duck for honoring a vow to his deeply religious mother never to play baseball on Sundays.

Wesley Branch Rickey had been born on November 20, 1881, in Scioto County, Ohio, to a poor farming family. He finished grade school, but then farm labor called. With help from a sympathetic retired educator, he read as widely as the resources of Scioto County allowed in the 1890s. He educated himself enough to become the teacher at the local grade school, saving money for college. Eventually, he went off to Ohio Wesleyan University. For the next decade, Rickey’s life was a welter of sporadic academics, sports, and, eventually coaching. He played baseball and football at Ohio Wesleyan and realized he could make money to pay for his studies. He spent part of several seasons in the majors, getting himself a reputation as a marginal catcher, a poor hitter, and an odd duck for honoring a vow to his deeply religious mother never to play baseball on Sundays.

In 1911, on the verge of 30, Branch Rickey graduated from law school and chose Boise, Idaho, as the site of his law office. He was, by his own accounts, a miserable failure. The impressions he had made as a baseball player and coach came to his rescue. Even while in Boise, he’d spent his summers scouting for Robert Hedges, owner of the American League’s St. Louis Browns. After his second unsuccessful winter in Boise, Rickey was only too happy to respond to Hedges’ request for a meeting in Salt Lake City to discuss a full-time job with the Browns. He borrowed the train fare from Hedges and began a half-century of life in professional baseball.69

By mid-1913, Rickey was the manager of the Browns. In 1916 a new Browns owner made him business manager, and a year later he moved to St. Louis’s National League entry, the Cardinals, in that role. He also added the job of field manager through the 1925 season. Rickey’s managerial record was mediocre and he gained a label as too much of a theorist, inclined to lecture his players how to do things, but unable to motivate them. The proof they pointed to was that in 1926, with the players Rickey had chosen and trained, but with Rogers Hornsby as manager, the Cardinals won their first pennant.

Rickey’s bosses and his rivals all recognized his brilliance as a baseball man, but thought he was too intellectual for the tobacco-stained game on the field. Baseball simply didn’t know what to do with him. In those days, baseball was a game of entrepreneurial owners, who functioned in the roles twenty-first-century teams split among a general manager, a business manager, a scouting director, and a president. It was only when Rickey was kicked upstairs from the Cardinals’ dugout that he found his true role. “Rickey practically created the office of business manager as it is understood today,” wrote the New York Times’ John Drebinger in 1943.70

Rickey’s first great innovation was the farm system. The Cardinals eventually created a chain of minor-league teams for which they could sign players cheaply, winnow the good from the great, win pennants, and make money. Rickey would sell the good to others and keep the great for the Cardinals.

By late 1942, Rickey’s relations with Cardinals owner Sam Breadon could best be described as rocky. Beginning in 1926, the Cardinals had won a third of the National League’s pennants plus four World Series. The team Rickey had constructed would win three more pennants and two World Series in the four years immediately after he left. Yet Sam Breadon was unhappy. He said Rickey earned more money than he did.71 The two were fighting over Rickey’s bonus payments and Breadon’s dismissal of Rickey protégés in the farm system.72 Rickey reportedly was upset at Breadon’s refusal to back him in a dispute with Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis, and with Breadon’s paying a large bonus to himself while cutting Rickey’s budget for salaries.73 Rickey was considering a top executive post with a large insurance company.74

In 1937, when Jim Mulvey first approached Rickey, he reportedly had been authorized to offer an ownership stake.75 Rickey had quietly been making inquiries about buying the Dodgers.76 Now there were even more compelling reasons for McLaughlin to facilitate this. The team’s finances had improved, but they were not solid, and the advent of World War II made the future of professional sports uncertain. With Rickey’s reputation, and the Dodgers’ financial improvement, it would be logical to think the trust company could fulfill more easily its responsibilities to the Ebbets and McKeever estates. A sale in which Branch Rickey gained some ownership and remained to run the team would be attractive to many potential buyers. Ownership was a positive inducement to complement Rickey’s desire to escape Breadon.

The wooing was relatively quick. The New York Times first reported Brooklyn-Rickey talks on October 4, 1942. The move was announced on October 29, a day when Rickey was introduced as the new general manager at a lunch at the Brooklyn Club.

Branch Rickey, Walter O’Malley and John Smith

George V. McLaughlin needed an exit strategy for Brooklyn Trust’s entanglement with the Dodgers and he was lining up the dominoes.

McLaughlin had multiple — at times conflicting — obligations centered on the Dodgers. The bank was a trustee of both the Charles Ebbets and Edward McKeever estates and thus bound to protect the heirs’ interests, getting them the greatest return possible on their Dodgers stock. And since much of the stock had been used as collateral for loans from the bank, a higher price for the stock would make it more likely that those loans would be repaid. Like the shareholders, the team still owed money to Brooklyn Trust and McLaughlin had to make sure his bank was repaid. The Dodgers were the most visible symbol of Brooklyn, and any misstep could be a public-relations boondoggle for the borough’s biggest bank. In early 1942 McLaughlin had attempted to end the bank’s role as trustee for the Ebbets heirs in part because of the bad publicity the bank was receiving for the perceived conflict of interest.77 He needed to sell the team to a person or a group who could satisfy the heirs, the bank, and the borough’s fans.

Branch Rickey was the first piece of the puzzle. For the team to pay off the debts, it would have to be successful and well managed. Who better to do that than Rickey? Success would be necessary to provide Rickey with the money he would need to buy a share of the team, and McLaughlin was in a position to make sure Rickey had the opportunity to buy. But there would have to be other pieces of the puzzle. Rickey would need partners with their own substantial funds. And McLaughlin would like to keep his own man around to make sure things continued to run well, someone who had both McLaughlin’s confidence and the skills to watch the business end of the team while Rickey concentrated on the baseball end.

McLaughlin’s choice was a 39-year-old lawyer named Walter Francis O’Malley. In the decade since he’d passed the bar, O’Malley had established a large practice mostly involved with bankruptcy cases, a lucrative niche during the Depression. He’d also become a protégé of McLaughlin’s, attending baseball games with the older man and sometimes pouring him into bed after a social evening. McLaughlin had ensured that O’Malley served on the boards of a number of troubled borough companies which, like the Dodgers, needed their finances restructured by Brooklyn Trust.78

Rickey had his own motivations for accepting O’Malley as the team’s lawyer. The Dodgers’ legal business had been handled by a large Wall Street firm that also represented the National League. Rickey recognized that the two might come into conflict and he wanted his own man.79 He also wanted to cut costs and consulted George Barnewall, who represented Brooklyn Trust on the Dodgers’ Board of Directors. Barnewall, not surprisingly, recommended O’Malley, and Rickey soon recognized that O’Malley was “the personal representative, in all legal matters, of Mr. George V. McLaughlin.”80

To all appearances, Walter O’Malley was a casual fan at that point. A boyhood interest in the Giants had evolved into a more practical relationship with the game. He recalled seeing his first Ebbets Field game about 1935, as his relationship with McLaughlin was flowering, and he became a box-seat holder because he could get better seats for entertaining clients there than he could at Yankee Stadium.81 Working with Brooklyn Trust’s financially troubled customers was the core of Walter O’Malley’s law practice, and adding a high-profile client like the Dodgers could only enhance his law firm’s reputation. “I never realized O’Malley would be this interested in baseball,” Rickey said later, but Rickey was impressed by how quickly O’Malley got a property near Ebbets Field condemned by city authorities so the Dodgers could use it.82

To all appearances, Walter O’Malley was a casual fan at that point. A boyhood interest in the Giants had evolved into a more practical relationship with the game. He recalled seeing his first Ebbets Field game about 1935, as his relationship with McLaughlin was flowering, and he became a box-seat holder because he could get better seats for entertaining clients there than he could at Yankee Stadium.81 Working with Brooklyn Trust’s financially troubled customers was the core of Walter O’Malley’s law practice, and adding a high-profile client like the Dodgers could only enhance his law firm’s reputation. “I never realized O’Malley would be this interested in baseball,” Rickey said later, but Rickey was impressed by how quickly O’Malley got a property near Ebbets Field condemned by city authorities so the Dodgers could use it.82

Rickey and O’Malley settled into their roles. Rickey began to remake the Dodgers roster and build up the farm system. O’Malley began learning the world of marketing, broadcasting contracts, ticket sales, and stadium operations. He would straighten out the bookkeeping system left by Larry MacPhail. The team’s on-field operations stumbled as players left for the military, but the business operations improved, and others noticed.

A number of offers for the team surfaced through the World War II years, especially as the end of the war appeared on the horizon.83 These offers highlighted another complication for McLaughlin. For the smooth future operations of the club, an ownership group that could exercise full control was necessary and that meant obtaining both the Ebbets shares and one of the McKeever blocs. As the team’s banker, McLaughlin had watched throughout the 1930s as the team’s management stagnated while the 50-50 stock split of the McKeever and Ebbets blocs strangled daily operations, much less attempts to deal with long-term problems. Rickey noted that the bank had found it impossible to get an offer for the Ebbets shares throughout that decade because potential buyers knew their investment would bring them not control, but a few seats on the Board of Directors with the necessity of sitting through rancorous, often unproductive meetings.

Rickey and O’Malley, who had been discussing the potential problems that new ownership could produce, began exploring. They clearly had the inside edge with the bank, but they had to raise the money, which they knew would be $240,000. “Mr. O’Malley took hold of things at this point,” wrote Rickey. O’Malley put down $25,000 of his own money to get an option on the Ed McKeever heirs’ shares.84

Rickey was a man who constantly lived at the edge of his income and would have to borrow to enter ownership. O’Malley could come up with his share and put down the option money, but they needed partners. By March 1944 Rickey was soliciting old acquaintances, but didn’t want to get too many more people involved.85 By the fall, another social and business acquaintance of McLaughlin and O’Malley entered the fold. He was Andrew Schmitz, a highly successful insurance executive with Brooklyn ties. Rickey borrowed $20,000 from Brooklyn Trust in September and the purchase of the Ed McKeever bloc closed on October 27.86

The newspaper accounts focused on Rickey’s move into ownership, with lesser attention paid to Schmitz and O’Malley. But several of the stories noted that this was only a preliminary to gaining the Ebbets shares and full control of the team.87

The Ebbets shares would be harder as the Ebbets family was divided, borrowed to the hilt on their shares and fully lawyered up. Many rested their hopes for the future on the sale of their Dodger stock. Ebbets had divided his estate among his second wife, four children by his first wife, and various grandchildren. The will was also encumbered by promised annuity payments to his first wife and son. By 1944 the Surrogate’s Court handling the case had 59 separate claimants or litigants, many of whom had borrowed money from Brooklyn Trust using the team’s stock as collateral. The file contained claims from 25 law firms totaling $150,000.88 O’Malley would have to guide an offer through the Surrogate’s Court that satisfied all parties.

While O’Malley worked behind the scenes, other potential buyers clouded the public picture. Early in 1945, the Brooklyn American Legion announced that it was interested in buying the team.89 Rickey and his partners said little in public and didn’t respond to the Legion’s request to see the books.90 The Legion’s offer dribbled into silence.

For the partners, anxious to strike a deal with both Brooklyn Trust and the Surrogate’s Court for the Ebbets shares, the problem these offers presented was the price they were willing to pay. The Legion had said it would pay $2 million for all the shares. (The Yankees had recently sold for $2.8 million). Another bidder said he would pay $1 million for the Ebbets shares alone. Both of these offers ran up against the problem that had dogged the club since Ebbets’ death. The Ebbets shares, even at $1 million, wouldn’t buy control, but only a chance for head-butting. For the Legion, the Mulvey share, and presumably the Rickey-O’Malley partners share, weren’t for sale at all, leaving their bid in limbo. Nevertheless, the price that was being put on half the franchise was $1 million, more than the $650,000 the partners hoped to pay, or the $750,000 they were willing to pay.91 And Brooklyn Trust, with its fiduciary duty to the trustees, had seen both offers.

By early May 1945, the partners were making their first formal offer for the Ebbets shares, and examining how they could finance it out of team revenues.92 In June, the Surrogate’s Court refused the $650,000 offer at the behest of the Ebbets heirs. In July, with the bid raised to $800,000, the court approved the sale. It was announced in mid-August. In all the newspapers, it was Rickey who had bought the team, with his partners relegated to the lower paragraphs. In the Brooklyn Eagle, Harold C. Burr confidently reported that the sale gave Rickey “absolute control of the Dodgers, to run as he pleases.”93

In the background, that control was not so clear, as events were to prove over the next five years. The partnership had changed in important ways. When the sale of the Ed McKeever estate’s shares had been announced the previous year, the buyers had been presented as Rickey, O’Malley, and Schmitz. Silent in the background was a fourth partner, John L. Smith, president of Brooklyn-based Pfizer Chemical. In May, while they were making their first formal offer, the group had approached James Mulvey about buying 5 percent of his family’s 25 percent share of the team. This 5 percent was to be split among Rickey and his three partners, giving each of the five shareholders 20 percent of the team assuming the partners bought the Ebbets shares. Such a distribution would prevent 50-50 standoffs in the boardroom.94 Mulvey was not interested.

The failure of this gambit led Schmitz to drop out of the partnership.95 And it led McLaughlin to require a partnership agreement among Rickey, O’Malley, and Smith to prevent boardroom stalemates. This agreement was to set the stage for governing the team over the next five years, and set the ground rules that led to O’Malley’s final control. In the agreement, Rickey, O’Malley, and Smith agreed that they would each own 25 percent of the team separately, but that they would pool their shares for purposes of voting in the boardroom.96 Thus, if there was a disagreement between, say, Rickey and O’Malley, whoever could swing Smith to his point of view would control how 75 percent of the stock was voted.

Smith’s role was also enhanced because he had the money to make the deal go smoothly. Brooklyn Trust had agreed to finance the triumvirate’s purchase. The $240,000 to purchase the Ed McKeever shares was turned over into a new financial package totaling $1,046,000, a sum that also included buying out Schmitz. The bank loaned the triumvirate $650,000 against the value of the Dodgers stock. O’Malley and Smith financed the remainder of their shares out of their own pockets. Rickey borrowed $99,500 from the bank using stock and life-insurance policies as collateral. With his personal assets used up, the bank loaned him another $72,000 based on guarantees from Smith and O’Malley.97 Smith could have handled his share with a check, but chose to go along with his partners in the overall financial agreement.

When he died in 1950, the headline on John Lawrence Smith’s New York Times obituary called him a “noted chemist,” a label the unassuming executive would have appreciated.98 It wasn’t until later that the story mentioned he was a part-owner of the Brooklyn Dodgers. To the nonbaseball world, Smith had made his name as an executive of Charles Pfizer & Co. and especially for his role in leading the Brooklyn company’s pioneering effort in the mass production of penicillin. His leadership was critical in moving Pfizer from a chemical supplier into an international pharmaceuticals giant.99

But to the baseball world of the late 1940s, Smith was the pivot on which the ownership of the Dodgers balanced. His financial resources and his relationship with McLaughlin made him a useful partner, and he soon struck up a relationship with Rickey based on their parallel rags-to-riches stories and their religious sympathies. With O’Malley, the tie was less significant, but older. As a young man, Smith had worked with Edwin O’Malley on the Hollis Volunteer Fire Company. After a fire, Smith would slip Walter and his friends a few dollars for sodas when they did the dirty work of rolling up the wet hoses.100

Smith was born in Krefeld, Germany, on February 10, 1889, as Johann Schmitz, the son of Gottfried and Johanna Schmitz.101 Krefeld was a center of the German velvet industry and Gottfried moved his family to Stonington, Connecticut, in 1892 to pursue opportunities in Stonington’s velvet mills. While they spoke German at home, the family formally changed its name to Smith in 1918, presumably as the result of anti-German agitation during World War I. John, who was naturalized in 1908, used the anglicized version from the time he entered the working world.

In 1914 he got his degree in chemistry, married Mary Louise Becker and moved to E.R. Squibb, where he oversaw the development of a large-scale ether-making facility at Squibb’s Brooklyn plant. By 1919, he returned to Pfizer, becoming plant superintendent. He would remain at Pfizer the rest of his life.

Smith continued to work his way up, emphasizing frugal management and research. During World War II, under his management, Pfizer would become the first company to figure out how to manufacture penicillin inexpensively in large volumes. In the first half of 1943, enough penicillin was produced to treat about 180 severe cases. In the second half, production could handle over 9,000 cases. By D-Day, it was just under 40,000 cases worth of production per month. Half of the world’s penicillin was coming from Pfizer’s Brooklyn plants, and the price per dose had dropped from $20 in early 1943 to $1. The company’s first public stock offering was oversubscribed and the shares value soared on Wall Street.102 Smith’s reward was Pfizer’s presidency in 1945.

One of Smith’s favorite ways to relax was to go to Ebbets Field of an afternoon to watch the Dodgers. He was encouraged in this relaxation by George V. McLaughlin, president of the Brooklyn Trust Company, which served as the bank for Pfizer and most of Brooklyn’s largest companies.

Reading the minutes of the board meetings from 1945 to 1950, it’s easy to see each member constantly returning to his major concern. With Rickey, the emphasis is on acquiring and nurturing talented players. With Smith, it is about economy and using money wisely. With O’Malley, it is about renovating or replacing Ebbets Field. Within the context of their ownership agreement, it was always a triangular discussion as each partner sought the ally he needed to carry his position. Smith had no ambitions to run the Dodgers. His partners, however, were men of ambition and confidence and each knew because of the partnership agreement that Smith was the key ally.

Murray Polner, a sympathetic Rickey biographer who was the first to have access to Rickey’s papers, argues that Rickey and Smith admired each other as self-made men and devout Christians. “Eventually, when Smith lay dying of cancer, O’Malley would wean him away and turn him against Rickey,” Polner writes.103 But the minutes of the board of directors meetings and the press reports of the time paint a picture of Smith considering a host of issues over several years before he counseled his wife to vote with O’Malley in the partnership agreement after his death.

Two years before Smith died, John Drebinger was writing in the New York Times that “the majority stockholders, represented by Walter O’Malley and John L. Smith, were not seeing eye-to-eye with Brother Rickey on a number of things.”104 That same year, Jimmy Powers, forever a Rickey critic, wrote, “The rumor mill is working overtime these days producing hints that Branch may not be as firmly anchored in his Brooklyn post as he used to be.”105

The reasons for Smith’s decision are found in a host of issues, in which he allied himself at various times with both of his partners. But they are rooted in his own path to success, investing for the future while keeping costs down.

The Dodgers were profitable throughout the late 1940s, but John Smith saw economies that could have made them even more profitable. As a young Pfizer executive, he had required his people to justify a request for a new pencil by producing the stub of the old one. When he gave his first major interview as an owner, the reporter’s questions were all framed around Rickey’s reputation as “El Cheapo.” Eventually, Smith counterattacked. “I have read that Rickey is cheap. As treasurer of the Brooklyn club, I think he is extravagant. He makes financial gambles you wouldn’t dare make in any other business.”106 By 1949, the board granted Smith’s request to go deeply into the company’s books.107

Most historians and biographers of the period have approached the story of Rickey, O’Malley, and the Dodgers through the lens of Jackie Robinson or the team’s Rickey-created successes on the field. But it is clear that O’Malley and Smith, the experienced businessmen on the board, used an additional lens. In March 1949, the board minutes reported, “Mr. Rickey was authorized, as usual, to use his best judgment in the baseball department of the corporation’s activities.”108 While the “as usual” affirmed and limited Rickey’s primacy to one area, the whole of the sentence clearly implied O’Malley and Smith’s determination to get involved in the business end.

Some of the early disagreements were indicative. Rickey, on moral grounds, was opposed to beer sponsorships for the radio broadcasts, even when he was having trouble finding sponsors.109 There were regular disagreements over the farm system, where Rickey’s focus on producing future talent collided with O’Malley’s desire to save money to refurbish Ebbets Field or build a new ballpark. While the farm teams were generally profitable in this period, there were significant costs in scouting and acquiring players.110

Smith did not move firmly into O’Malley’s camp immediately. There were important issues on which they disagreed or which aroused Smith’s tightfisted ways. Smith supported Rickey’s investment in the Vero Beach training camp, which could both train all 700 or so Brooklyn minor leaguers and provide a bubble within Florida’s Jim Crow laws for the team’s African Americans. O’Malley balked at the money needed to turn a naval base into a baseball facility. Smith also was suspicious of a contract O’Malley signed with a company to provide maintenance for Ebbets Field. After several years of growing questions, Smith insisted that he, rather than O’Malley, negotiate the contract for 1949.111

O’Malley and Smith constantly deferred to Rickey in baseball matters, but they would use their experience to judge his performance as a businessman.112

Rickey’s biggest management blunder, however, came in football. He was persuaded, against O’Malley and Smith’s judgment, to take over the Brooklyn Dodgers of the fledgling All-American Football Conference. The team lost money in 1948, and then was merged with the New York Yankees of the same league.113 It lost more money in 1949, approximately equal to an annual profit for the baseball team. At the last meeting before Smith’s terminal illness in early 1950, the size of the football loss was revealed and this apparently contributed mightily to Smith’s telling his wife to vote with O’Malley in board matters.

The trigger for O’Malley’s buyout of Rickey was the latter’s contract. For its time, it was very lucrative. It called for an annual salary of $50,000 plus 10 percent of the team’s annual profit and a $5,000 expense account that Rickey didn’t have to account for. In the five years of the extended contract, Rickey would earn just over half a million dollars in salary, expense accounts, and bonuses. Then there was $43,312.50 in his share of the stockholder dividends declared by the board. Over the same years, the highest paid Dodger player would earn less than $120,000.114 The contract was due to run out in October 1950.

Ultimately, it was a game of King of the Mountain, with Smith serving as the referee. Branch Rickey had been trying to get into ownership since his earliest days with the St. Louis Browns and he wasn’t about to give it up easily now.115 “Rickey wanted a one-man operation, which he hadn’t been able to get in St. Louis,” said New York newspaperman Leonard Koppett, who covered baseball beginning in the late 1940s.116 Bill Veeck would later slap at O’Malley for his way of getting his way, but he also said, “Papa Branch is incapable of moving into any kind of any organization without maneuvering to establish himself as the dominant force.”117 Or, as Jane Rickey said of her husband, “No one could make friends easier than Branch. But he can’t take a back seat.”118 Nor could anyone accuse Walter O’Malley of being less than ambitious.

There were also different styles. Branch Rickey was a Midwestern Methodist Victorian and proud of it. He counseled all his players to marry. He wanted nothing to do with alcohol, or Democrats. Even with all his innovations in baseball, he was a man whose concept of marketing was to put a talented, interesting team on the field and let the fans flock to it. The reporters were a necessary evil.

O’Malley, like Smith, was a product of the corporate world. Owners owned. Managers managed. Players (employees) played. It was to be a cooperative effort aimed at maximizing profits, but it was not a cooperative. You needed to market your product and innovate off the field as well as on. You needed to coddle the reporters, who were your best source of free publicity.

And there were differences in style. Both men could be charmers, but O’Malley was more apt to slap your back, buy you a drink, and tell some jokes, many with a little sting at the end. Rickey retained a lot of the farmboy, and O’Malley was New York City born and bred. Both were masters at parsing their sentences, their meanings, and their implications like surgeons. They could dodge a question or cover it with ambiguity as they felt the situation demanded.

Ebbets Field in Brooklyn during its 1950s heyday. (National Baseball Hall of Fame Library)

Rickey Leaves, O’Malley Triumphant

By the summer of 1950, with Smith beginning to criticize, Rickey clearly had moved beyond any thought of staying with the Dodgers.119 The terms of the partnership agreement began to exercise their control. Any partner wishing to sell must offer the others the chance to buy his shares. When Rickey approached O’Malley, he was offered $346,666.66 for his shares, the price he, O’Malley, and Smith had paid in 1944 and 1945. This was not the $1 million price tag Rickey had established in his own mind, a price that was far closer to the real value of the franchise.120

O’Malley clearly was lowballing Rickey. Apparently he calculated that no one would pay much for a nonmajority interest in a team where O’Malley’s influence over the Smith bloc would leave him in control. He would also say he was concerned for Mrs. Smith, as a sale at $1 million would raise the taxes on her husband’s already substantial estate.121 It was a sentimental argument that he knew buttressed his desire to pay less, but it also was an argument that knit Mrs. Smith closer to O’Malley.122

In addition, O’Malley knew Rickey was, as usual, hocked to his substantial eyebrows.123 O’Malley evidently hadn’t paid attention to a situation a year earlier when one owner of the St. Louis Cardinals had leveraged a similar agreement and an outside offer to gain a higher price from his partner.124 The partnership agreement gave Rickey a similar right to find an outside buyer whose presumably higher offer would have to be matched. Walter O’Malley had miscalculated.

Rickey had a fraternity brother named John Galbreath, a highly successful real-estate developer based in Columbus, Ohio. Galbreath was a part-owner of the Pittsburgh Pirates who had substantially raised his stake that summer and assumed the team’s presidency.125 Galbreath was looking for a baseball man to run the team. Rickey was looking for a buyer willing to pay $1 million for his shares. Who approached whom isn’t clear, but Galbreath eventually referred Rickey to a New York real-estate man named William Zeckendorf.

Rickey spent two meetings with Zeckendorf and his associates. Arthur Mann reported that Zeckendorf was at first resistant to Galbreath’s overtures. Playing to Galbreath’s love of horse racing, Zeckendorf asked, “(W)ould you buy a racing stable if they retired the best horse (meaning Rickey)?”126 Assured Rickey would stay if he bought in, Zeckendorf began to listen. He didn’t balk at the $1 million price tag, but was taken aback when Rickey told him the partnership agreement would force Rickey to allow O’Malley to counteroffer. “You’re using me to force a price. I can’t tie up capital” for that. Rickey agreed to a $50,000 fee for Zeckendorf if O’Malley bought the stock.127

On Friday, September 22, 1950, Rickey presented the offer to O’Malley and Mrs. Smith. Brooklyn Eagle sports editor Lou Niss broke the story on page 1 the next day.

O’Malley said immediately that he would match the offer.128 Dick Young of the New York Daily News described O’Malley as “stunned” and “peeved.”129 For years, O’Malley would complain that Zeckendorf wasn’t a real buyer, simply doing Galbreath a favor and pocketing $50,000 in the process.130 But Zeckendorf described himself as a real baseball fan. He had made an earlier attempt to buy the St. Louis Browns.131

The newspapers were most concerned with whether Rickey was moving to Pittsburgh, whom O’Malley might name as general manager and whether Burt Shotton would return as the manager for 1951. Two New York papers reported that Mrs. Smith’s shares were for sale, an unlikely event as her husband’s estate was deep in probate court.132

O’Malley was most concerned with where he was going to raise $1 million. He said he intended to take full advantage of the 60-day window to come up with the money.133Three weeks later, O’Malley started to show his hand. He announced that he and Mrs. Smith would buy out Rickey, and each would own 37.5 percent of the team.134 Two days later, Rickey resigned. In early November few were surprised to learn that he had joined the Pirates as executive vice president and general manager.135 His contract was virtually identical to the contract O’Malley had offered him two months earler.136

O’Malley was still struggling to raise the money. He formally accepted the $1,025,000 offer on November 1.137 Mrs. Smith dropped out of her agreement to participate in buying the Rickey stock on November 20.138 Whether this had been contemplated all along isn’t clear. Rickey’s success in winning his price was certainly an additional financial burden for her husband’s estate.139 O’Malley now had to come up with the full price by himself. He was helped by the terms Rickey had negotiated with Zeckendorf, which called for a 10-year payoff. On November 24 he wrote Rickey that he’d match those terms, paying $175,000 down on December 5 and another $125,000 by March 1, 1951. The remaining $750,000 would be paid in 10 annual installments beginning in 1952.140 The payments over the next decade could be financed out of the Dodgers’ earnings.141

O’Malley’s path to full ownership was accomplished quietly over the next quarter-century. In 1957 he bought out Mrs. Smith’s one-quarter share and divided it with the Mulveys. O’Malley now owned two-thirds of the team and the Mulveys the rest.142 After the deaths of Dearie (1968) and Jim (1973), the Mulvey heirs sold their stock to O’Malley in January 1975.

Los Angeles City Councilwoman Rosalind Wyman, a strong Dodger supporter throughout the maneuvering to bring the team to Los Angeles and build Dodger Stadium, presents a commendation from the Beverly Hills B’nai Brith to owner Walter O’Malley. (Courtesy of the Los Angeles Dodgers)

The rise of cable television owners

Shortly afterward, columnist Jerome Holtzman wrote that there were reports the Dodgers were for sale, reports denied quickly by the Dodgers. Holtzman reported that O’Malley was willing to sell only if he got his price, which was said to be $45 million in December 1977 and $50 million to $60 million nine months later.143 This was clearly a substantial gain over the $300,000 at most that he had laid out from his own wallet in the 1940s. He had also forgone several million in Dodger profits that were spent buying out the original bank loan, and later paying off Rickey, Mrs. Smith, and the Mulveys. Even if the team was for sale, O’Malley evidently didn’t get his price.

With O’Malley’s death in 1979, the Dodgers passed in a trust to his two children, Teresa and Peter, with Peter running the club.

With Peter as chairman and his sister and her husband sitting on the board, the Dodgers continued to set attendance records. In the 18 years from 1980 through 1997, the second-generation O’Malley management drew average attendance of over 3 million a year.

But other issues were clouding Peter O’Malley’s horizon. By 1997 he was approaching 60. His sister was four years older. He had three children and she had 10. A possibly very costly tax situation was approaching if they tried to pass team control intact to the next generation. When Peter announced that the team was for sale in January of that year, the necessity for estate planning was the first reason he gave.144

He also said he thought the days of family ownership of franchises had passed. Only corporations would have the financial depth to handle higher payrolls, absorb time lost from strikes, and smooth out the ups and downs. Too much of the family’s wealth was tied up in one business.

There were also some issues O’Malley didn’t address. The influence at the national level that Walter and then Peter O’Malley had exercised during the Bowie Kuhn years had dwindled with each successor as commissioner until he helped oust Fay Vincent, a move he later regretted.145 Another key factor was a failed initiative by O’Malley to win a National Football League franchise and build it a new facility on the Dodger Stadium property. The city council’s decision to push for the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum site foreclosed what O’Malley saw as a way to stabilize the family’s assets and income.146

O’Malley said his “responsibility was to find the best possible owner for the ballclub.” He added, “I think commitment to the community, to Los Angeles, to Southern California (are) the No. 1 criteria.”

Buying interest was immediate. Former Commissioner Peter Ueberroth said he’d like to buy the team.147 Corporations such as Arco (oil), Sony (electronics), and Nike (sporting goods) had their names trotted out.148

The name that kept coming back, however, was the Fox Group, the US television arm of Rupert Murdoch’s News Corp. For Fox, it was a natural. They already had local television contracts with 21 of the 30 major-league teams. They were trying to build up their Fox Sports West channels in the Los Angeles area, where the Walt Disney Co. and its ESPN affiliate planned to start a rival sports channel but needed a baseball team and its 162 games of programming to provide a foundation.149

In May 1997 O’Malley allowed as how Fox and the Dodgers were in serious negotiations, something Fox confirmed two days later.150 By mid-August, they were close to an agreement in principle and received permission from Major League Baseball to open the Dodgers’ books to Fox.151 Less than three weeks later, the deal was struck. Fox would get the franchise, the Dodger Stadium property, and the team’s training complexes in Vero Beach, Florida, and the Dominican Republic. Over the next several months, the Associated Press would consistently report the selling price as $350 million, while the Los Angeles Times would quote “sources” as saying $311 million and the New York Times would peg it at $320 million.152