Jim Creighton

James Creighton was the greatest pitcher of his day. Famous principally for his exploits on behalf of the champion Excelsiors of Brooklyn in the years 1860 to 1862, he possessed an unprecedented combination of speed, spin, and command that virtually defined the position for all those who followed. Prior to Creighton, pitchers had been constrained by the rule that “the ball must be pitched, not thrown, for the bat.” This meant that (a) the ball had to be delivered underhand, in the stiff-armed, stiff-wristed manner borrowed from cricket’s early days and (b), in the absence of called strikes, an innovation of 1858, or called balls, which came into the game six years later, the ball had to be placed at the batter’s pleasure: the infant game of baseball was designed to display and reward its most difficult skill, which was neither pitching nor batting, but fielding.

James Creighton was the greatest pitcher of his day. Famous principally for his exploits on behalf of the champion Excelsiors of Brooklyn in the years 1860 to 1862, he possessed an unprecedented combination of speed, spin, and command that virtually defined the position for all those who followed. Prior to Creighton, pitchers had been constrained by the rule that “the ball must be pitched, not thrown, for the bat.” This meant that (a) the ball had to be delivered underhand, in the stiff-armed, stiff-wristed manner borrowed from cricket’s early days and (b), in the absence of called strikes, an innovation of 1858, or called balls, which came into the game six years later, the ball had to be placed at the batter’s pleasure: the infant game of baseball was designed to display and reward its most difficult skill, which was neither pitching nor batting, but fielding.

The 1850s did produce some pitchers who tried to deceive batters with “headwork”- which meant changing arcs and speeds, and sometimes bowling wide ones until the frustrated batter lunged at a pitch. (The latter tactic produced such incredible, documented pitch totals as that in the second Atlantic-Excelsior game of 1860, when the Atlantics’ Matty O’Brien threw 325 pitches in nine innings, Creighton 280 in seven.) On balance, however, the pioneer pitcher and batter were collaborators in putting the ball in play rather than the mortal adversaries they have been ever since Creighton added an illegal but imperceptible wrist snap to his swooping low release.

Known to few fans today and an unlikely, if deserving, candidate for the Baseball Hall of Fame, Jim Creighton was a remarkable embodiment of transecting trends in America and in baseball: cricket vs. baseball, amateur vs. professional, North vs. South, playing by the rules or playing with them. The legion of baseball players followed along the path that Creighton blazed. In life he was a star performer, but it was his startling death that transformed his life into legend.

Born to James and Jane Creighton on April 15, 1841, in Manhattan, Jim moved to Brooklyn with his widowed father in February 1858, when he was age 17. Indeed, his baseball precocity may have secured for him and his father a fine income.1 By the age of 16, his abilities in cricket and baseball had become evident, particularly with the bat. He and some neighborhood youths started a junior baseball club, which they called Young America. It played a handful of games in 1857, and then disbanded. Jim then joined the fledgling Niagaras of Brooklyn, for whom he claimed second base. Playing shortstop was George Flanley, another accomplished young player.

In 1859 the Niagaras challenged the Star Club, then the crack junior team. In the fifth inning of the game, with the Niagaras trailing badly, their regular pitcher, Shields, was replaced by Creighton. Peter O’Brien, captain of the Atlantics, witnessed this game, and “when Creighton got to work,” he observed, “something new was seen in base ball—a low, swift delivery, the ball rising from the ground past the shoulder to the catcher. The Stars soon saw that they would not be able to cope with such pitching. Their captain, after consulting other base ball players present, sent in his wildest pitcher. They, by these tactics, were enabled to win the game, which resulted in the breaking up of the Niagara Club, and Creighton and Flanley at once joined the Stars. The next year he with Flanley joined the Excelsior Club.” 2

How to explain all this movement? That old snake in the garden: money. In the 1860s such restlessness came to be termed revolving; today it would be called free agency. According to the sporting press, Creighton was a high-principled, unassuming youth whose gentlemanly manner and temperate habits were ideal attributes for the amateur age of baseball; all the same, he became (at the same time as Flanley) baseball’s first professional, through under-the-table “emoluments” from the Excelsiors, who were hungry to surpass the rival Atlantics. Just as he changed the game forever more by breaking the rule against the wrist snap, so did he assure that skilled baseball players could never again be content with field exercise followed by groaning banquets.

In 1860 the Excelsiors embarked on the first tour by any baseball club, with stops in Albany, Buffalo, Canada, Philadelphia, Washington, and Baltimore, among others. That year, in 20 match games, Creighton scored 47 runs while being retired only 56 times. Not once did he strike out. He also started baseball’s first recorded triple play, on September 22, and threw baseball’s first recorded shutout, on November 8.

But the best was to be saved for last. After another championship campaign in 1861, Creighton went through the 1862 season as not only the game’s peerless pitcher but also its top batsman, being retired only four times, either in plate appearances or on the basepaths.

At the same time that Creighton was extending the frontier in baseball he was also a prominent member of the cricketing fraternity. The national sport of England and its boyish variants like wicket had been played in America since the Colonial period, and the first formal American cricket club had taken shape in Boston in 1809 (the Union Club of Philadelphia followed in 1832, and the St. George of New York in 1838). When the all-England team crossed the Atlantic to play against (and drub) selected American clubs at the Elysian Fields and elsewhere, Creighton took part in the contests. In a match of 11 Englishmen against 16 Americans, Creighton clean bowled five wickets out of six successive balls. English Cricketer John Lillywhite, on seeing Creighton pitch a baseball, instantly saw the dilemma that overmatched American batsmen faced: “Why, that man is not bowling, he is throwing underhand. It is the best disguised underhand throwing I ever saw, and might readily be taken for a fair delivery.”3

Cricket continued to be a source of pleasure and profit for Creighton through the next two years, during which he and the Excelsiors were proving themselves to be the top baseball team in the land. Coincidentally, several other Excelsiors were good enough at cricket to play for established clubs – John Whiting, A. T. Pearsall, John Holder, and Asa Brainard, later to become famous as Creighton’s successor with the Excelsiors and as the pitcher for the undefeated Cincinnati Red Stockings of 1869. Creighton performed for the American Cricket Club in both 1861 and 1862, joined by Brainard in both years but with John “Death to Flying Things” Chapman of the Atlantics taking the place of the Virginian Pearsall in 1862; he had returned to Richmond when hostilities broke out to enlist in the Confederacy.

In 1861 Brainard and Creighton had jumped the gentlemanly Excelsiors for the working-class Atlantics, no doubt lured once again by covert lucre. After three weeks, without having played a game in the hated rivals’ uniforms, the pair sheepishly returned to the fold.

On October 14, 1862, in a match against the tough Unions of Morrisania, Creighton played the field while Brainard pitched the first five innings. In four trips to the plate, he hit four doubles. In the sixth he came in to pitch, and then in the next inning something happened. John Chapman later wrote: “I was present at the game between the Excelsiors and the Unions of Morrisania at which Jim Creighton injured himself. He did it in hitting out a home run. When he had crossed the [plate] he turned to George Flanley and said, ‘I must have snapped my belt,’ and George said, ‘I guess not.’ It turned out that he had suffered a fatal injury. Nothing could be done for him, and baseball met with a severe loss. He had wonderful speed, and, with it, splendid command. He was fairly unhittable.” 4

Creighton had swung so mighty a blow – in the manner of the day, with hands separated on the bat, little or no turn of the wrists, and incredible torque applied by the twisting motion of the upper body – that it was reported he ruptured his bladder. (Later review of the circumstances, aided by modern medical understanding, pointed to a ruptured inguinal hernia.) After four days of hemorrhaging and agony at his home at 307 Henry Street, Jim Creighton passed away on October 18, at the age of 21 years and 6 months, having given his all to baseball in a final epic blast that Roy Hobbs (the cinematic one, that is) might have envied.

But is that the way it really happened? Creighton’s last run home instantly ascended to the realm of myth, giving baseball its martyred saint. Obsequies included such syrupy statements as: “He was very modest, and never severe in his criticisms of the play of others. He did not care to talk about his own playing, was gentlemanly in his deportment, and very correct in his habits, and to sum up all, was a model player in our National Games [understood here not as a typo, but signifying baseball and cricket]. His death was a loss not only to his club but to the whole base ball community, which needed such as he as a standard of honorable play and ability.”5 Rule-breaking, revolving, sub rosa professionalism, all were now to be dismissed. Icon-making was in full production.

Creighton’s Excelsior teammates mourned his loss at their black-draped clubhouse at 133 Clinton Street and subscribed toward a fine monument over his remains, in Brooklyn’s Greenwood Cemetery. (Both the clubhouse and the monument are still standing, and represent two of baseball’s oldest and greatest shrines; if you go to Greenwood to pay homage to Creighton, as I did, stop at Henry Chadwick‘s gravesite, too. I signed baseballs to each and placed them on top of their tombs; you’ll know what to do.) But the Excelsiors were not at all sure that it was a good thing for baseball to take the blame for Creighton’s death; this might not promote the healthful properties of the new game. What if his injury had been sustained a day or two earlier, say, at a cricket match?

According to a contemporary account, at the National Association convention of 1862, the Excelsior president, Dr. Jones, “briefly made allusion to the death of Creighton, and paid high tribute to his memory; in doing which he availed himself of the opportunity to correct a mis-statement that has found its way into print in reference to his death being caused by injuries sustained in a baseball match. This, he said, was not so; the injury he received in a cricket match.”6

The battle for the nation’s sporting allegiance was at a crucial point. Cricket had been the favored sport until only recently, when the Excelsior tour and Creighton’s exploits had created a mania for baseball and had elevated it into parity. Now, with Creighton gone and the Excelsiors falling back into the pack, might the British import be restored to primacy? These fears may have been running through the minds of some in the baseball community, already concerned with the new game’s incipient professionalism, and thus may have moved them to propagandize for baseball’s spotlessness, as well as Creighton’s. Jim had carried the game to new heights; in death he would prove even more useful.

Smart lad, to slip betimes away

From fields where glory does not stay

And early though the laurel grows

It withers quicker than the rose.

— A. E. Housman

Creighton preserved, even enhanced, his purity by dying young. Celebrated though he was, at the time of his demise he was not the game’s greatest player – by general acclamation the laurels went to his catcher, Joseph B. Leggett. Who hears of him today? (I know, who hears of Creighton – well, at least a thousand for every one that recognizes Leggett’s name.) Creighton died when he was all potential – no possibility of loss through aging, change, even growth. He became a plaster saint onto whom one could project whatever social or moral values one wished to promote in the population at large. Cut off in his prime, he joined other such deified national figures – mostly martial ones like Nathan Hale or Davy Crockett. Those golden boys who die young, from Arthur Rimbaud to Harry Agganis, from Charlie Ferguson to Buddy Holly, from Ernie Davis to Lyman Bostock, are forever young in the land of might have been, safe.

A Johnny Appleseed of baseball through his role in the grand tour of 1860, Creighton won far-flung fame. His death, coming as it did “in action” and at a time when the nation was preoccupied with the destruction of a generation, became emblematic of the losses of the Civil War. At the end of all the carnage, the lamented pitcher even became a symbol of national reconciliation.

On July 5, 1866, the Nationals of Washington visited the Excelsiors, reciprocating the favor of their visit six years earlier. The Brooklyn team gave them a warm reception, capped by a visit to Creighton’s monument (according to the New York Times report, “a silent tear was dropped to the memory of the lamented James Creighton, whose beautiful monument is a prominent feature of the city of the dead.”)7 Two years later, a team in Norfolk, Virginia took the name “Creightons.” And in 1872 a Creighton club was formed in Washington, D.C. Oddly, on this team named in homage to the fallen hero – whose appetite for money had given rise to professionalism and, even in his lifetime, gambling – was a young player named Albert Nichols who in 1877 would be one of the four Louisville players expelled from baseball for game-fixing.

In death Creighton’s real accomplishments rapidly took on an accretion of myth, much as his death itself may have. Baseball, today universally recognized as a vibrant anachronism, was not always a backward-looking game in which the plays and players of yore set unsurpassable standards of excellence. In the 1850s and ’60s, baseball was new, and strictly a “go ahead” business, in the watchword of the day. Creighton’s death implanted the game with nostalgia. More than 20 years after his passing, veteran observers might say without fear of challenge that Keefe and Radbourn were fine pitchers, sure, but they “warn’t no Creighton.”

Sources

Most of my research into the exploits of baseball’s first great pitcher was conducted at the New York Public Library, where I found news clippings among the Chadwick and Spalding scrapbooks. Odd bits –Clipper and Mercury notes, as well as Will Rankin columns from the Charles Mears Collection at the Cleveland Public Library were also helpful. Retrospective notes about the late lamented Creighton were plentiful in the decade after his death, and beyond. The National Chronicle, The Ball Players’ Chronicle, and the Beadle Guides supplied good material, as did The Spirit of the Times and the Baltimore Sun

Secondary sources provided some additional data, but these are potential land mines for the researcher, as even the basic facts of Creighton’s death were in dispute before the body was laid to rest. Tom Shieber’s excellent reconstruction of the medical facts underlying Creighton’s fatal injury was valuable.

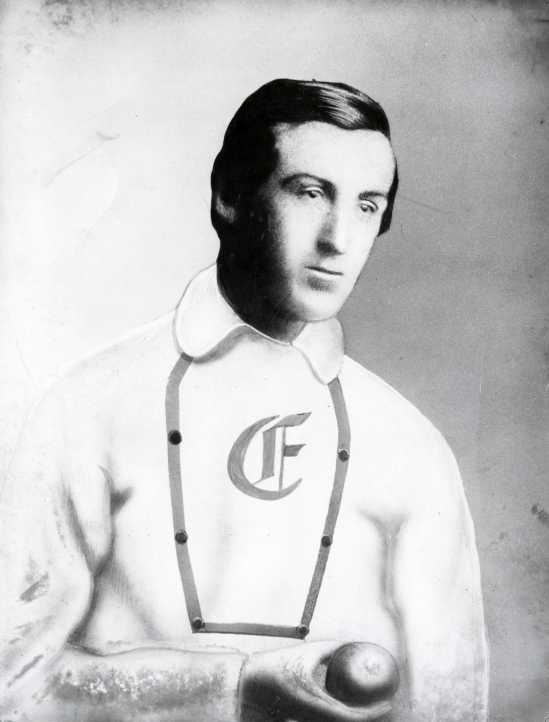

In 1983, if memory serves correctly, Mark Rucker and I were scouring the photo archives of the Northeast, public and private, looking for images of nineteenth century baseball to fill our upcoming “special issue” of The National Pastime. At the Culver Studio in New York City, we came upon several great finds, one of them a unique carte de visite of Jim Creighton posed in the backswing of his pitching motion. Glued to the back of the card was a tattered and torn biographical note, likely issued three or four years after his death and as such a testament to his already legendary status.

Here is the text of that note, transcribed as the fragments permitted; gaps are noted with an ellipsis:

“It would be useless to attempt to do justice to the many qualities that rendered James Creighton so popular a member of the baseball and cricket fraternity. His is a record that […] may well be proud of, and although he was taken away … age of … in his brief career, made such a clear […] has a […] dear to every base ball player in …. [other gaps in paragraph indecipherable].

“James Creighton was born in New York city … a child his parents removed him to Brooklyn, where they […] resided. When base ball was first introduced in this [city?] Creighton took a great interest in the game, and with the assistance of several others, started a little club which was known as the Young America, which, however, lasted but a brief season. He next assisted in starting the Niagara Club, for whom he played second base, George Flanley, now captain of the Excelsior club (18__) [1864?] playing short stop.

“They played many matches in which they were successful, which gave them such a confidence in their prowess that they resolved to play the Star Club, then the crack Junior Club, and it was in this match that Creighton gave evidence of those qualities that afterwards made him so renouned [sic]. On the fifth inning of this game, when the Stars were a number of runs ahead of the Niagara the pitcher of the latter was changed, Jimmy taking that position. Peter O’Brien witnessed this game, and when Creighton got to work something news [sic] was seen in base ball — a low, swift delivery, the ball rising from the ground past the shoulder to the catcher. The Stars soon saw that they would not be able to cope with such pitching. Their captain, after consulting [other?] base ball players present, sent in his wildest pitcher. They, by these tactics, were enabled to win the game, which resulted in the breaking up of the Niagara Club, and Creighton and Flanley at once joined the Stars. The next year he with Flanley joined the Excelsior Club. He was very modest, and never severe in his criticisms of the play of others. He did not care to talk about his own playing, was gentlemanly in his deportment, and very correct in his habits, and to sum up all, was a model player in our national Games. His death was a loss not only to his club but to the whole base ball community, which needed such as he as a standard of honorable play and ability. The Excelsior Club erected a fine monument over his remains, in Greenwood. Members of other clubs attended his funeral, and at times even [wept over?] the grave where poor “Jim” lies. His age at the time of [his death?] was twenty-one years and six months.”

A version of this biography is included in “Nuclear Powered Baseball: Articles Inspired by The Simpsons Episode Homer At the Bat” (SABR, 2016), edited by Emily Hawks and Bill Nowlin. For more information, click here.

Notes

1 Outstanding research on Jim’s father, his recruitment by Brooklyn baseball clubs, and his likely sub rosa payments, appears here: Tom Gilbert, “Searching for James Creighton,” Base Ball, 2014: 17-35.

2 Creighton posed for a photographer in the backswing of his underhand motion; the image is preserved as the front of a carte de visite issued after his death. Glued to the back of the card was a tattered and torn biographical note, the source of the Pete O’Brien quotation cited. Mark Rucker and I found his card in the archives of Culver Pictures in 1983.}

3 New York Clipper, August 5, 1911: 12.

4 Alfred Henry Spink, National Game, 128. Spink credits the Chapman quote to “a recent article in the Boston Magazine.”

5 Creighton carte de visite, op. cit.

6 Albert Spalding Baseball Collections, Chadwick Scrapbooks, vol. 5 (Clipper, 1862, undated: 293).

7 “Out-Door Sports,” New York Times, July 7, 1866: 8.

Full Name

Creighton

Born

April 15, 1841 at New York, NY (US)

Died

October 18, 1862 at New York, NY (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.