Eight Myths Out: Appendix of errors in ‘Eight Men Out’ book and film

In conjunction with SABR’s Eight Myths Out project, here are specific examples of factual errors or misinformation that appear in Eight Men Out, both the 1963 best-selling book written by Eliot Asinof and the 1988 film directed by John Sayles.

Certain entries on this list may seem like pedantic nitpicking: surnames misspelled, Abe Attell’s boxing record exaggerated, erroneous player batting averages presented. Other, more significant, errors may be deemed somewhat excusable, as accurate baseball player salary data, partial Black Sox grand jury transcripts, and other recently recovered scandal artifacts were not available to Asinof when Eight Men Out was being written.

But some of the book’s failings — unquestionably bogus 1919 player salary numbers presented as bona fide, the distortion of events attending the theft of grand jury confession evidence, the assertion of fix cover-up theories grounded in “facts” belied by the contemporaneous historical record — cannot be so lightly dismissed. If nothing else, the sheer number of factual errors and misstatements in Eight Men Out undermines confidence in the credibility of its narrative.

In fairness to Asinof, baseball literature had not yet outgrown its anecdotal roots at the time Eight Men Out was published. A factually scrupulous narrative with copious citation of source materials, now expected of serious baseball works, had not yet become the norm. That said, Eight Men Out suffers greatly from the absence of a knowledgeable fact-checker and rigorous peer review.

Large and small, here is a list of what Asinof and Sayles got wrong in both versions of Eight Men Out.

Click on a link below to scroll down to that section:

Errors in the 1963 Eliot Asinof book

- Part I: Factual errors and misstatements made by Eliot Asinof

- Part II: Fictional characters, invented dialogue, and manufactured events

- Part III: Narrative omniscience in Eliot Asinof’s Eight Men Out

Errors in the 1988 John Sayles film

- Part I: Factual errors in John Sayles’ Eight Men Out

- Part II: Fictional characters and invented scenes

Note: All page numbers listed below are from the 1987 Owl Book paperback edition of Eight Men Out.

EIGHT MEN OUT: THE 1963 BOOK BY ELIOT ASINOF

PART I: FACTUAL ERRORS AND MISSTATEMENTS MADE BY ASINOF

1. Preface; p. xii: “Rothstein’s partner, Nat Evans, dies in 1959, permitting [Asinof informant] Abe Attell, another ex-Rothstein associate, to reveal his participation in the fix.” Fact: Nat Evans died in a Manhattan hospital on February 6, 1935. See Bruce Allardice’s comprehensive bio of Nat Evans for the SABR BioProject, citing the Evans obituary and a follow-up article published in the Saratoga Springs (New York) Saratogian, February 6 and 10, 1935.

2. Preface, p. xii: “Three of the eight ball players signed confessions, but they were stolen from the Illinois State’s Attorney’s Office before trial.” Facts: There were no signed confessions in the Black Sox case. Actually stolen from the Cook County (not Illinois) State’s Attorney’s Office were the original typed transcriptions of the grand jury testimony of Eddie Cicotte, Joe Jackson, and Lefty Williams. Like all grand jury testimony transcripts, these documents were unsigned. The theft was discovered well in advance of trial, and the missing transcripts were recreated with the handwritten shorthand notes of grand jury stenographers Walter J. Smith and Elbert Allen. During the Black Sox criminal trial, the grand jury testimony of Cicotte, Jackson, and Williams was read to the jury at length, as reported in the Chicago Herald Examiner, Chicago Tribune, and elsewhere, July 26, 1921.

3. Preface, p. xiii: “Many of the sources spoke in complete privacy and chose to remain anonymous. Many dialogues and incidents recounted in the book are the result of invaluable reminiscences of these people.” Fact: As revealed by Asinof himself years later, he had only two 40-years-after-the-fact, insider-type scandal informants: White Sox outfielder Happy Felsch and gambler Abe Attell. None of the other surviving Black Sox players would speak to Asinof about the fix, while the in-the-know gamblers besides Attell were long dead. See Eliot Asinof, Bleeding Between The Lines (New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1979). For exposure of the often-imaginary nature of the “many dialogues and incidents recounted in the book,” see Part II, below.

4. Page 11: “In 1878 … the St. Louis weekly The Spirit of the Times published…” Fact: The Spirit of the Times was published in New York City. [Note: Asinof may have confused the paper with The Sporting News, published in St. Louis beginning in 1885.]

5. Page 11: “In 1876, the Louisville Club had the pennant all but clinched … [but] they began throwing games.” Fact: The Louisville game-throwing scandal occurred during the 1877 season. See William A. Cook, The Louisville Grays Scandal of 1877: The Taint of Gambling at the Dawn of the National League (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2005).

6. Page 13: Regarding the effects of American entry into World War I in 1917, Eight Men Out states: “the government shut down race tracks for the duration.” Fact: This is categorically untrue. See Wikipedia or any other encyclopedia-type source for the names of Triple Crown and other horseracing stakes winners during 1917-1918. See also, Gene Carney, “Notes from the Shadow of Cooperstown,” No. 439, March 20, 2008.

7. Page 15: Re Chicago White Sox club owner Charles Comiskey: “his ballplayers were the best and were paid as poorly as the worst.” Fact: This is the central myth of the Black Sox scandal. Analysis of player salary cards and related evidence now reposited at the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library in Cooperstown establishes that the 1919 White Sox had one of the highest player salary payrolls in baseball. See Bob Hoie, “1919 Baseball Salaries and the Mythically Underpaid Chicago White Sox,” Base Ball, A Journal of the Early Game, Vol. 6, No. 1, Spring 2012, 17-34. (Note: Use password “McFarland” to open the PDF.)

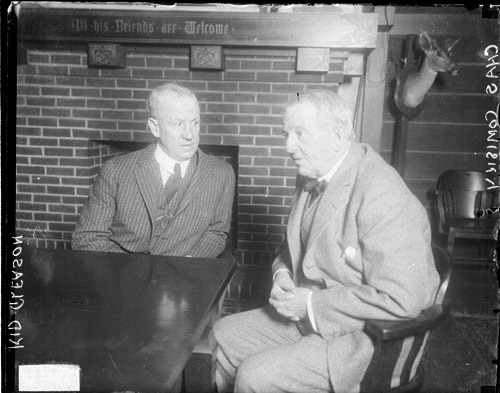

Chicago White Sox owner Charles Comiskey, right, and manager Kid Gleason talk in a room at Comiskey Park during the 1919 season. (CHICAGO HISTORY MUSEUM, CHICAGO DAILY NEWS COLLECTION)

8. Page 16: Regarding Eddie Cicotte’s salary for the 1919 season: “Many players of less stature got almost twice as much on other teams.” Fact: Cicotte’s 1918-1919 compensation made him the second-best paid pitcher in major-league baseball. Only Washington Senators ace Walter Johnson made more money. See Bob Hoie, “Black Sox Salary Histories, Part II,” The Inside Game, Vol. XIII, No. 2, May 2013, 23-24.

9. Page 18: “Gandil set out after … George ‘Buck’ Weaver, ‘Shoeless’ Joe Jackson, and Oscar ‘Happy’ Felsch. Somehow Gandil got them all to a [fix conspiracy] meeting on the following night.” Fact: The grand jury testimony of Eddie Cicotte (which Asinof did not consult) places Jackson at the Ansonia Hotel meeting. But according to all other accounts (Lefty Williams, Sleepy Bill Burns, Billy Maharg, as well as Jackson himself), Joe Jackson never attended a fix conspiracy meeting.

10. Page 19: “On September 21, the eight ballplayers assembled after dinner in Chick Gandil’s room at the Ansonia [Hotel for a fix meeting].” Fact: Joe Jackson was likely not present during the fix meeting at the Ansonia. See above.

11. Pages 20-21 include contrast of salaries paid to members of the 1919 Chicago White Sox as opposed to those paid to the Cincinnati Reds. “Compared with their 1919 World Series rivals from Cincinnati, [White Sox salary] figures seemed pitiful. Outfielder Edd Roush … made $10,000. Heinie Groh, at third base, topped Weaver’s [$6,000] salary by almost $2,000. First baseman Jake Daubert … earned $9,000. It was the same all around the leagues. Many second-rate ballplayers on second-division ball clubs made more than the White Sox.” Facts: The player salary data at the Baseball Hall of Fame establish that Buck Weaver was paid $7,250 in 1919; Reds counterpart Heinie Groh made less, $6,500. Edd Roush’s salary for the 1919 season was also $6,500 (not $10,000), while Jake Daubert played that year for $5,000. The total player payroll of the National League (not second division) Cincinnati Reds was more than $11,5000 less than that of the 1919 Chicago White Sox. See again, Hoie, “1919 Baseball Salaries,” 27-29. See also, Jacob Pomrenke, “1919 American League Salaries,” Scandal on the South Side: The 1919 Chicago White Sox (Phoenix: SABR, 2015), 294-298.

12. Page 21-22: “There were betrayals too. Like Comiskey’s promise to give Cicotte a $10,000 bonus in 1917 if he won 30 games. When the great pitcher threatened to reach that figure, it was said that Comiskey had him benched.” Facts: The 1917 bonus claim (and the one for 1919 made in the Sayles film) has been completely discredited by modern Black Sox researchers Rob Neyer in Bill James’s The Baseball Book 1990 (New York: Villard, 1991), Gene Carney in Burying the Black Sox: How Baseball’s Cover-Up of the 1919 World Series Fix Almost Succeeded (Washington, DC: Potomac Books, 2006), and Bob Hoie, “1919 Baseball Salaries.” Nor was Cicotte prevented from winning 30 games either season, as he was given the late-campaign starts needed to achieve 30 wins, bonus or not. See Retrosheet, 1917 and 1919 Chicago White Sox game logs. See also, Gene Carney, “The Mysterious Mr. Cicotte,” in Mysteries from Baseball’s Past: Investigations of Nine Unsettled Questions, Angelo J. Louisa and David Cicotello, eds. (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2009), 93-94.

13. Page 26: “In Rothstein’s entourage, there was a unique little man. Raised in San Francisco, with the name Albert Knoehr, he later changed it to Abe Attell. For twelve years, this little man had held the featherweight championship of the world.” Facts: Reputedly born on Washington’s Birthday in 1883, Attell’s birth name was Abraham Washington Attell. He was the son of Jonas Attell and his wife Sarah (nee Semel), and the older brother of world bantamweight champion Monte Attell. For the Attell family tree posted by a great-grandson of another boxing Attell brother (Caesar, a decent West Coast middleweight), click here. Abe Attell won the world featherweight crown in 1904, lost it later the same year, and thereafter reigned as featherweight champion from 1906 to 1912.

14. Page 26: Abe Attell “fought 365 professional fights, was beaten only six times. He was never knocked out. He weighed no more than 116 pounds.” Facts: Whatever his other failings, Attell was a great fighter, and a durable one. But he had nowhere close to 365 pro fights. The authoritative boxing records website BoxRec credits Attell with 157 bouts. Attell’s 18 losses (not six) include the 5th-round round knockout by Tommy Sullivan in 1904 that cost him the featherweight belt and three late-career TKOs. In Attell’s day, the featherweight limit was 122 pounds (now 126) but like most lighter champions, he often fought over the division weight limit in non-title bouts.

15. Page 27: In 1912, Attell “lost the [featherweight] championship to Johnny Kilbane and finally quit the ring.” Fact: According to BoxRec, Attell had 15 more bouts after losing the crown to Kilbane, finally retiring after a January 1918 TKO loss to Phil Virgets.

16. Page 42 and thereafter: Misspells the surname of Black Sox gambler defendant David Zelcer.

17. Page 42 and thereafter: Refers to Chicago gambling kingpin Mont (Jacob) Tennes as “Monte” Tennes.

18. Page 46: Christy “Mathewson had been assigned to cover the [1919] Series by the New York World.” Fact: Mathewson was special World Series correspondent for the New York Times. See e.g., Christy Mathewson columns published in the New York Times, September 30 through October 10, 1919.

19. Page 49: During his major-league playing career, White Sox club owner Comiskey had been a “fair hitter (lifetime average .269).” Fact: According to the authoritative site Baseball-Reference.com, Comiskey compiled a lifetime .264 batting average.

20. Page 52: During his career as a major league pitcher, White Sox manager Kid Gleason “had won 129 games and lost the same number.” Fact: Per Baseball-Reference, Gleason’s record was 138-138.

21. Page 60 and thereafter: Chronic misspelling of Cincinnati pitcher Dutch Ruether’s surname.

22. Page 60: “Cicotte was fully aware that the Cincinnati pitcher, Dutch Reuther [sic], after two years in the majors, was getting almost double” Cicotte’s salary. Fact: Ruether’s 1919 salary was $2,340, far less than that of Cicotte. See again, Hoie, “1919 Baseball Salaries,” 28-29.

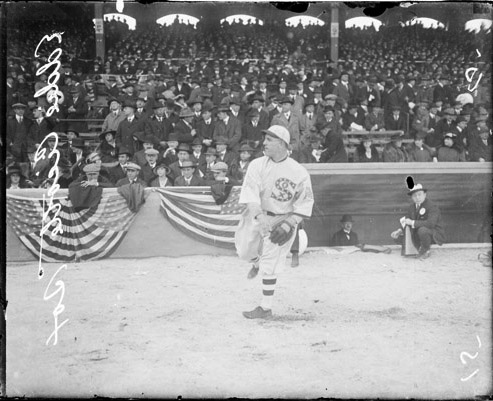

Chicago White Sox pitcher Eddie Cicotte, shown warming up before a game during the 1917 World Series, was the second-highest paid pitcher in the American League behind Walter Johnson, according to salary records maintained by the National Baseball Hall of Fame. (CHICAGO HISTORY MUSEUM, CHICAGO DAILY NEWS COLLECTION)

23. Page 62: For Game One, the home plate umpire was “black-suited John Rigler.” Fact: Umpire Cy Rigler’s rarely-used first name was Charles. See the SABR BioProject profile of Cy Rigler by David Cicotello.

24. Page 74: National Commission chairman Garry Herrmann “was also owner of the Cincinnati Reds.” Fact: Herrmann was club president of the Cincinnati Reds, but had only a small stake in club ownership. The principal owners of the 1919 Reds were the Fleischmann brothers, Julius and Max. See William A. Cook, August “Garry” Herrmann: A Baseball Biography (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2008).

25. Pages 130 and 134: Include the Levi brothers among the St. Louis gamblers involved in the fix. Fact: Ben and Lou Levi were from Kokomo, Indiana. See Bruce Allardice, “The Levi Brothers: Kokomo’s Black Sox Gamblers,” SABR Black Sox Scandal Research Committee newsletter, Vol. 6, No. 2, December 2014, 8-10.

26. Page 130: Identifies Maclay Hoyne as the “Illinois State’s Attorney.” Fact: Hoyne was the Cook County (Chicago) State’s Attorney.

27. Page 136 and elsewhere: Misspelling of the surname of sportswriter John B. Sheridan.

28. Page 137: Gives the major league pitching record of Babe Ruth through the 1919 season as “90 wins, 39 defeats.” Fact: According to Baseball-Reference, Ruth’s 1914-1919 pitching log was 89-46.

29. Page 140: States that in the 1919 offseason, Sox boss Comiskey offered Joe Jackson a three-year contract at $9,000 per season. Fact: The contract offer (which Jackson accepted) was for three years at $8,000 per season. See Bob Hoie, “Black Sox Salary Histories, Part I,” The Inside Game, Vol. XIII, No. 1, February 2013, 5.

30. Page 140: Joe Jackson “had a fine year in 1919, batting .354, second only to [Ty] Cobb.” Facts: Per Baseball-Reference, Jackson batted .351 that year, coming in fourth in the American League batting race behind Cobb (.384), Bobby Veach (.355), and George Sisler (.352).

31. Page 143: Angry by his apparent blacklisting, Lee Magee “hired a lawyer and challenged the National League Commissioner, John Heydler, to do battle.” Fact: Heydler was the President (not Commissioner) of the National League.

32. Page 147: According to Asinof, Joe Jackson batted .385 in 1920. Fact: According to Baseball-Reference, Jackson hit .382 that season.

33. Page 152: Gets wrong the first name of the Black Sox grand jury foreman. He was Henry (not Harry) Brigham.

34. Page 153: “Chief Justice Charles MacDonald [sic] of the Criminal Courts Division, an ambitious man, was clearly eager to ride an investigation for whatever it was worth. Hoyne had no choice but to give him the green light. The Grand Jury would be summoned.” Facts: Apparently, Asinof did not understand that the grand jury is an arm of the judicial branch of government, not the executive. As presiding judge, McDonald (not MacDonald) did not require the approval, permission, or “green light” of State’s Attorney Hoyne to convene a grand jury and commence an investigation of unlawful gambling on baseball. McDonald could act unilaterally.

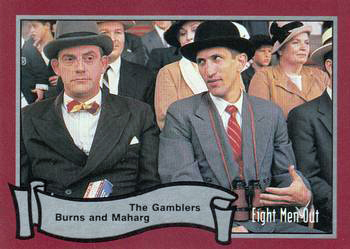

35. Page 162: Describes Billy Maharg as “a tough, burly middleweight.” Facts: According to BoxRec, Maharg stood just over 5-foot-4, and fought as a lightweight (135 pounds).

36. Page 162: Maintains that veteran Philadelphia North American sportswriter James Isaminger “had reason to believe his real name was not Maharg at all. It was George Frederick Graham — Maharg spelled backwards, if you will. ‘Peaches’ Graham, the ballplayer had been a catcher in the big leagues for about ten years.” Facts: Billy Maharg was born William Joseph Maharg, one of three children born to Philadelphia laborer-turned-farmer George Alexander Maharg and his wife, the former Catherine Carney. The inane claim that Billy Maharg and Peaches Graham were the same person was invented by Black Sox criminal defense lawyers in Chicago, not Philly sportswriter Isaminger who knew both men. For more detail, see the author’s SABR BioProject profile of Billy Maharg.

37. Page 175: States that Joe Jackson telephoned Judge McDonald’s chambers from the Jackson apartment. Fact: According to Jackson himself and others, he made the telephone call to McDonald from the law office of Alfred Austrian, corporate counsel for the Chicago White Sox. See the Chicago Tribune, September 28, 1920.

38. Page 177: Describes Joe Jackson as “red-eyed, unshaven, smelling of alcohol” when he entered Judge McDonald’s chambers. Facts: Newspaper photographs of Jackson taken that same afternoon show him clean shaven and nattily dressed, and reveal no visible sign of dissipation. See e.g., Jackson photos published in the Chicago Daily News, September 29, 1920. Nor do Jackson’s responsive and coherent answers under questioning before the grand jury show signs of excessive drinking or other impairment. See Transcript of Jackson Grand Jury testimony, September 28, 1920.

39. Page 177: Presents as fact the Jackson claim that he was promised non-prosecution by Austrian prior to his grand jury appearance. Fact: This claim was disputed by prosecution witnesses and rejected as not believable by Judge Hugo M. Friend after a mid-trial courtroom hearing conducted outside the jury’s presence. See the Chicago Herald Examiner, Chicago Tribune, and Savannah Daily News, July 26, 1921. See also, William F. Lamb, Black Sox in the Courtroom: The Grand Jury, Criminal Trial and Civil Litigation (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2013), 118-124.

40. Page 177: Alleges that Alfred Austrian presented Jackson with a waiver of immunity which Jackson signed prior to entering the grand jury room. Fact: As reflected in the transcript of the Jackson grand jury testimony, Jackson was read his rights by Assistant State’s Attorney Hartley Replogle and signed the waiver of immunity in the grand jury room in the presence of the grand jury members. See grand jury testimony of Joe Jackson, [JGJ] page 1, lines 5 to 22.

Shoeless Joe Jackson, right, speaks with Assistant State’s Attorney Hartley Replogle at the Cook County Courthouse in Chicago. Jackson testified to the grand jury that he accepted a $5,000 bribe from gamblers to throw the 1919 World Series. On the field, he tied a World Series record with 12 hits, including the Series’ only home run. (COURTESY OF BLACKBETSY.COM)

41. Page 177: States that Jackson told the grand jury about being propositioned about the fix and his “gradual feeling out by Gandil and Risberg. They had been at him for days.”‘ Fact: As reflected in the grand jury record, Jackson testified that he was approached about the fix privately by Chick Gandil. Swede Risberg was not involved in Jackson’s recruitment. See JGJ 5-11 to 13; JGJ 20-11 to 24.

42. Pages 177-178: States that Jackson finally “agreed, but he got only $5,000 — $5,000 in a dirty envelope, delivered to his room by Lefty Williams. He’d get the other $15,000 after the Series — after he had delivered the goods. He took Lefty’s word for it.” Fact: Nowhere does such testimony appear in the grand jury record. Rather, Jackson told the panel that he was supposed to be paid a portion of his $20,000 payoff after each Series game, an arrangement reached with Gandil. See JGJ 6-17 to 24.

43. Page 178: Continues the recitation of purported Jackson testimony before the grand jury by quoting the complaints that Jackson made to Gandil and Risberg about not getting “the rest of his dough. If [he did] not, he was going to squawk. They told him: ‘You poor simp. Go ahead, etc.’” Facts: The above remarks do not appear in the transcript of the Jackson grand jury testimony. Rather, Jackson made his complaints about the payoff shortchange to reporters gathered outside the grand jury room after he had completed his testimony. See the Chicago Journal, Chicago Tribune, Cincinnati Post, and New Orleans State, September 29, 1920.

44. Page 178: Jackson informed the grand jury that “he hadn’t played good baseball, despite his incredible .375 World Series average.” Fact: Here, Asinof reiterates a canard about the Jackson testimony published over the Associated Press wire. See e.g., the Los Angeles Times, September 29, 1920. In fact, Jackson said no such thing. Despite agreeing to the fix and later accepting a $5,000 payoff, Jackson testified that he had played to win at all times during the Series. See JGJ 11-11 to 24; JGJ 12-20 to JGJ 13-24.

45. Page 178: “Jackson rambled on [before the grand jury] for about two hours.” Fact: The Jackson grand jury transcript indicates that the afternoon session of September 28, 1920 began at 1:00 p.m., but that Jackson did not testify until 3:00 p.m. The transcript does not specify the time when Jackson was excused. But based on the writer’s professional experience (which includes over 4,000 grand jury appearances during 30+ years as an urban New Jersey prosecutor), the testimony embodied in the 29-page transcript would have consumed no more than 20 minutes, tops.

46. Page 198: Declares that baseball executives felt threatened by “the District of Columbia Supreme Court Decision of April, 1919, that marked baseball as a combination in restraint of trade, a violation of the Sherman Anti-Trust Act.” Facts: The “decision” was a bench ruling on a legal question by Justice Wendell Philips Stafford made during a jury trial conducted in the United States District Court for the District of Columbia, a trial-level tribunal, not an appellate level or supreme court. For more and comprehensive analysis of the complex legal questions involved, see Nathaniel Grow, Baseball On Trial: The Origins of Baseball’s Antitrust Exemption (Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press, 2014).

47. Page 210: on September 29, 1920, “Sport Sullivan … learned that Lefty Williams had named him before the Illinois Grand Jury.” Fact: The Williams testimony was given to the Cook County grand jury.

48. Page 212: Asserts that in October 1920, Sport Sullivan fled to Mexico per instructions of attorney William J. Fallon, the architect of post-indictment defense strategy. Fact: Sullivan, a resident of Sharon, Massachusetts, did not go anywhere. He remained a local presence observed almost daily in nearby Boston by the Boston police, as reported by the Boston Globe on April 27, 1921.

49. Page 217: Asserts that prior to Arnold Rothstein’s appearance before the Cook County grand jury, attorney Fallon accompanied him to a meeting with White Sox counsel Austrian in Austrian’s Chicago law office. Facts: Although he used Fallon as a sort-of behind the scenes consigliere, Rothstein was never represented by Fallon (during the Black Sox case or at any other time, as Rothstein was troubled by Fallon’s drinking and erratic behavior). More to the point, Fallon never left New York during the Black Sox case. On the October 26, 1920 date of Rothstein’s meeting with Austrian and grand jury testimony, Fallon was on his feet in the Manhattan courtroom of Judge Joseph F. Mulqueen, successfully opposing a prosecution motion to postpone the imminent trial of conspiracy/war bonds robbery charges against Fallon client Nicky Arnstein, as reported (with mention of Fallon by name) in the New York Evening World, October 26, 1920. See also, “Arnstein Bond Case Is Ready for Trial,” New York Herald, October 26, 1920, and “Arnstein Trial Is Set for Early Next Week,” New York Tribune, October 26, 1920.

50. Page 218: States that “For the first and only time during its lengthy session, a witness was permitted the company and support of counsel during questioning. William J. Fallon accomplished this by holding that condition as the price of his client’s testimony. If they wanted Rothstein, they had to take Fallon with him.” Facts: Negotiations to get Rothstein, a New York resident beyond the subpoena power of the Cook County grand jury, to appear and testify voluntarily were conducted with Rothstein attorney Meier Steinbrink, not Fallon. See the Chicago Tribune and Richmond Times-Dispatch, October 20, 1920. Nor did Fallon accompany Rothstein to Chicago; Fallon never left New York City. See 49, above. While he was in Chicago, Rothstein was accompanied by another of his regular attorneys, Hyman Turchin, as reported in the Chicago Evening Post, October 26, 1920, and confirmed by the testimony of Alfred Austrian at the trial of the civil lawsuit later filed by Jackson in Milwaukee. Austrian identified Hyman Turchin as the attorney attending Rothstein at the October 26, 1920 meeting held in the Austrian law office. See Transcript of Jackson Civil Trial, pp. 929-937. The historical record, however, yields no evidence that Turchin, or any other lawyer, was present in the grand jury room during the Rothstein testimony.

51. Page 218: Says State’s Attorney “Maclay Hoyne treated [Rothstein] like a friendly witness. His questions presumed Rothstein’s innocence, spared him the possibility of embarrassment.” Facts: Apart from an October 1, 1920 appearance to endorse the grand jury’s work to date, Hoyne never set foot inside the grand jury room. The questioning of witnesses in the Black Sox probe was done by his subordinates, usually ASA Hartley Replogle, occasionally assisted by ASA Ota P. Lightfoot. For a detailed account of the grand jury proceedings, see Lamb, Black Sox in the Courtroom, 37-79.

52. Page 225: “The Illinois Grand Jury finally completed its investigation. On October 22, [1920], it handed down its final indictments.” Facts: This is wrong. The Cook County grand jury’s work was far from finished on October 22. On October 26, the grand jury took the testimony of witnesses Arnold Rothstein, St. Louis Browns second baseman Joe Gedeon, East St. Louis gambler Harry Redmon, and J.G. Taylor Spink and Al Herr of The Sporting News. Three days later, AL president Ban Johnson and Chicago Chief of Police John J. Garrity appeared before the panel. See again, Lamb, Black Sox in the Courtroom, 72-74 and contemporaneous authority cited therein. The grand jury formally returned its Black Sox case indictments on the afternoon of October 29, 1922, as reported in the Chicago Herald Examiner, Chicago Tribune, and newspapers nationwide, October 29-30, 1920. On November 6, the panel concluded its work by delivering a six-page report on the baseball pool-selling aspect of its investigation, and returning indictments against three baseball pool operators, as reported in the Chicago Daily News and Chicago Evening Post, November 6, 1920. The grand jurors were thereupon discharged from service with the thanks of the court by Judge McDonald. See the Chicago Tribune, November 7, 1920.

53. Page 226: States that “before [lame duck incumbent] Hoyne left office, he had a mission to perform. Along with an assistant, Henry Berger, he went to the files in which the voluminous Grand Jury testimony was kept. … The real purpose of the maneuver was plunder. Berger, already familiar with the material, knew exactly what to look for. Fallon had been explicit enough [and wanted Berger to remove any transcript excerpts mentioning Rothstein]. Hoyne, meanwhile, had a simpler assignment: he lifted the confessions of Cicotte, Jackson, and Williams along with the waivers of immunity they had signed before giving testimony.” Facts: The numerous errors in this narrative include identification of Henry Berger as a Hoyne assistant. More than a year earlier, Berger had resigned his position in the Cook County State’s Attorney’s Office. See the Chicago Tribune, May 4, 1919. At the time of the incident, Berger was in private practice and had been retained by Fallon as local Chicago counsel for Fallon client Abe Attell. See Bill Lamb, “Bulldog Barrister: Black Sox Defense Counsel Henry Berger,” SABR Black Sox Scandal Research Committee newsletter, Vol. 10, No. 1, June 2018, 12-17. When later confronted by Judge McDonald, Hoyne admitted collecting the grand jury material, explaining weakly that he wanted to make sure everything was in order for his successor, incoming SAO Robert E. Crowe. See the Boston Globe, Chicago Tribune, and Washington Post, December 8, 1920. Hoyne had no idea how the grand jury material had disappeared from his vault. Crowe later hauled Hoyne, Berger, and others connected to the Black Sox case before a Cook County grand jury, but the disappearance of the evidence remained a mystery. Some years later, Fallon’s friend and former law partner, disbarred attorney Eugene F. McGee, told Joe Vila of the New York Sun that Rothstein had given Fallon $50,000 to procure the grand jury minutes. Fallon then transmitted $15,000 to Berger who used the bulk of the money to bribe the actual thief, Hoyne’s office secretary George Kenney, as per correspondence and other material contained in the Black Sox Scandal file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

Maclay Hoyne was the Cook County State’s Attorney whose office led the grand jury investigation into the Black Sox Scandal in the fall of 1920. His secretary, George Kenney, stole the Black Sox grand jury transcripts and files from the office prior to the incoming SA Robert Crowe taking office, but the theft was discovered well in advance of the Black Sox criminal trial. The grand jury testimony was re-created from courtroom stenographers’ notes and read into the record during the trial. (CHICAGO HISTORY MUSEUM, CHICAGO DAILY NEWS COLLECTION)

54. Page 227: States that AL President Ban Johnson hired “two notable lawyers,” former ASA James “Ropes” O’Brien and George Barrett, to assist 2nd ASA George Gorman, the newly-designated lead trial prosecutor in the Black Sox case. Facts: Johnson retained O’Brien to represent American League interests in the proceedings. Recently-retired judge George Barrett was subsequently retained to replace O’ Brien after “Ropes” switched sides to represent defendant Chick Gandil. For more on this, see Lamb, Black Sox in the Courtroom, 89-90. Barrett argued a pretrial motion to delay the Black Sox trial denied by Judge William E. Dever in mid-March 1921. After that, no evidence of further participation by AL counsel Barrett in the Black Sox proceedings was discovered by the writer. O’Brien, meanwhile, represented Gandil through the not guilty verdict returned against him. See Bill Lamb, “Ropes at the Ready: Defense Counsel James C. O’Brien,” Black Sox Scandal Research Committee newsletter, Vol. 10, No. 2, December 2018, 10-13.

55. Page 227: States that lead trial prosecutor “George Gorman was a worried young man.” Facts: Gorman may have been worried, but he was hardly young. A one-time Illinois Congressman, Gorman had been admitted to the bar in 1895, and was the oldest and most experienced member of the Black Sox legal cast on either side. Gorman was also older and far more experienced than then-novice trial judge Hugo M. Friend.

56. Page 228: “Gorman spent the Fall [of 1920] ignoring the case and busying himself with other matters.” Fact: Gorman was not a member of the Cook County State’s Attorney’s Office in Fall 1920. He did not assume his position of 2nd ASA until the Crowe administration was installed in office in early December.

57. Page 230: States that during adjournment motion proceedings conducted in mid-March 1921, Gorman’s revelation that the Cicotte, Jackson, and Williams grand jury transcripts were missing “forced Judge Dever’s hand: he had to grant the State’s motion. He declared the entire case stricken from the call. This meant that the State would have to hand in new indictments.” Facts: This is entirely wrong. The court denied the adjournment motion, setting a peremptory May 2 trial date for the Black Sox case instead, as reported in the Chicago Journal, March 14, 1921, Boston Globe, March 17, 1921, and elsewhere. It was State’s Attorney Crowe (not Judge Dever) who then decided, for strategic reasons, on the grand jury do-over. Crowe administratively dismissed the original Black Sox indictments, coupling this stunning development with announcement that the matter would immediately be re-presented to a new grand jury for the return of superseding indictments. See the Chicago Journal, March 17, 1921, and Chicago Tribune and New York Times, March 18, 1921. Those superseding indictments were returned days later, as reported in the Chicago Tribune, Los Angeles Times, New York Times, and elsewhere, March 26, 1921.

58. Page 243: States that Judge Friend “acquiesced” in an eve-of-trial defense motion to interview prospective prosecution witnesses Bill Burns and Joe Gedeon. Fact: Judge Friend did not “acquiesce” in anything. His granting of the defense motion was compelled by an Illinois pretrial discovery statute. Perhaps curiously, the same statute that mandated prosecution witnesses submit to pretrial interview by defense counsel did not require the witnesses to answer any of the attorneys’ questions, and Burns and Gedeon did not.

59. Page 245 and elsewhere: Misspells the surname of prosecution trial counsel Edward A. Prindiville. Asinof also gets his title wrong. A former First Assistant, Prindiville had left the Cook County State’s Attorneys Office to enter private law practice in 1920. Newly installed SA Crowe retained Prindiville as a special prosecutor for the Black Sox trial. See “A Closer Look: Edward A. Prindiville,” SABR Black Sox Scandal Research Committee newsletter, Vol. 7, No. 2, December 2015, 12.

60. Page 254 and elsewhere: Misspells surname of Max Luster (not Lusker), defense counsel for gambler defendants David Zelcer (not Zelser) and the Levi brothers.

61. Page 257: Prosecutor “Gorman then advised the Court that the original copies of the signed confessions … had disappeared.” Fact: There were no “signed confessions” in the Black Sox case. See No. 2, above.

62. Page 259: “If there were carbon copies … [of the Cicotte, Jackson, and Williams grand jury confessions], at least there were no signatures on them.” Facts: There were no “carbon copies” of the grand jury testimony. The testimony was re-typed by the grand jury stenographers from their retained handwritten stenographic notes of the proceedings.

63. Page 257: Confuses the order of witness appearances, putting defendant David Zelcer on the witness stand before the prosecution had presented Billy Maharg and rested its case-in-chief.

64. Page 261: “Billy Maharg … had been mixed up in the fight game as a middleweight.” Fact: The weight limit for middleweight boxers is 160 pounds. According to BoxRec, Maharg fought as a lightweight (135 pounds).

65. Pages 267-268: Asinof fouls up the order in which the attorneys made their closing arguments to the jury. The correct order was Prindiville for the prosecution, followed by various defense counsel, then ending with brief rebuttal remarks for the prosecution by 2nd ASA Gorman. See Lamb, Black Sox in the Courtroom, 138-148, and contemporaneous sources cited therein.

66. Page 270: Like other commentators, Asinof misapprehends the significance of part of Judge Friend’s instructions to the jury on the issue of intent. For explanation regarding why this aspect of the court’s charge lacked the capacity to influence the verdict, see William Lamb, “Jury Nullification and the Not Guilty Verdicts in the Black Sox Case,” SABR Baseball Research Journal, Vol. 44, No. 2 Fall 2015, 54-55.

67. Page 271: Regarding Joe Jackson’s first experience in major-league baseball, Asinof relates that Jackson “never wanted to come North in the first place, back in 1909,” and how “he fled the first train ride to Philadelphia in the middle of the night.” Fact: Wrong year. Jackson first came north to join the Philadelphia A’s in 1908. See Shoeless Joe Jackson’s BioProject article by David Fleitz for details.

68. Page 272: After the Not Guilty verdicts had been rendered, “Cicotte leaped across the room and grabbed the juror, William Barrett, the foreman.” Fact: The jury foreman was William Barry (not Barrett). See the Chicago Tribune, July 16, 1921.

69. Page 275: Places the salary of newly installed MLB commissioner Landis at $42,500. Fact: Including his $7,500 expense account, Landis’s compensation as Commissioner was $50,000/year. See David Pietrusza, Judge and Jury: The Life and Times of Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis (South Bend, Indiana: Diamond Communications, Inc., 1998), 166-170.

70. Page 280: Confuses the chronology of events in the civil lawsuit instituted against White Sox by Buck Weaver. Facts: The Weaver lawsuit was not settled out of court in 1924. According to Black Sox researcher Gene Carney, settlement was not reached until 1930, with Weaver getting $3,500, or about half of his unpaid salary for the 1921 season. See Gene Carney, “Notes from the Shadows of Cooperstown,” No. 487, May 17, 2009.

71. Page 284: After their expulsion from Organized Baseball, the Black Sox “maintained a solid front of silence to the world. It was as if a pact existed between them and the forces that had brought them to it. It was a silence of shame and sorrow and futility.” Facts: While it is true that Happy Felsch was the only one who would speak to Asinof, Black Sox players spoke to many other writers about the scandal. For Joe Jackson, see Shirley Povich, “Say It Ain’t So, Joe,” Washington Post, April 11, 1941; Carter (Scoops) Latimer, “Joe Jackson, Contented Carolinian at 54, Forgets Bitter Dose in His Cup and Glories in His 12 Hits in ’19 Series,” The Sporting News, September 24, 1942; “This Is the Truth,” by Joe Jackson as told to Furman Bisher, Sport, October 1949. For Chick Gandil, see “This Is My Story of the Black Sox Series,” by Arnold (Chick) Gandil as told to Mel Durslag, Sports Illustrated, September 17, 1956. A complete accounting of statements uttered by the Black Sox is provided by Jacob Pomrenke in “No ‘Solid Front of Silence’: The Forgotten Black Sox Scandal Interviews,” SABR Baseball Research Journal, Vol. 45, No. 1, Spring 2016.

72. Page 286: Arnold Rothstein was fatally shot during a 1928 poker game but “principal suspect George McManus … was never prosecuted, for no one would talk.” Fact: McManus was indicted and brought to trial for the Rothstein murder, but a court-directed verdict of not guilty was returned during that trial by a Manhattan jury on December 5, 1929, as reported in the New York Times, New York Tribune, and elsewhere, December 6, 1929.

73. Page 289-290: Asinof provides a false and disingenuous account of the circumstances attending the acquisition and use of the transcript of the Jackson grand jury testimony by attorneys defending the White Sox corporation against the civil lawsuit filed by Jackson. This may have been the result of Asinof “not having the time” (or so Asinof told Black Sox researchers Gene Carney and David Fletcher years later) to make the trip to the law office of Jackson attorney Cannon necessary to review the civil trial transcripts while doing his Eight Men Out research. For detailed deconstruction of Asinof spin on the civil trial, see Lamb, Black Sox in the Courtroom, 167-177.

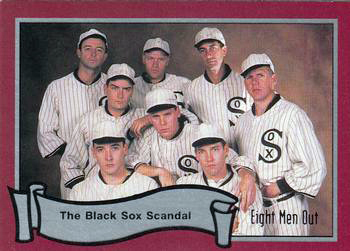

Former boxing champion Abe Attell, seen here in 1910, was one of the few living participants who agreed to an interview with Eliot Asinof, who was researching the Black Sox Scandal for “Eight Men Out” decades later. Attell, whose credibility in telling the truth was questionable, told Asinof a dramatic and compelling version of the 1919 World Series fix, but his story was only one part of a multi-faceted conspiracy that involved many other participants. (CHICAGO HISTORY MUSEUM, CHICAGO DAILY NEWS COLLECTION)

PART II: ASINOF FICTIONAL CHARACTERS, INVENTED DIALOGUE, AND MANUFACTURED EVENTS

A. Fictional Characters: As Asinof explains in Bleeding Between the Lines, a desire to keep the scandal action moving was not the only impetus behind the insertion of fictional characters in Eight Men Out. He was also acting on his attorney’s advice. At the time Asinof was fashioning his manuscript, he did not have the Black Sox to himself. Other treatments of the scandal were in the works. Historic events attending the corruption of the 1919 World Series were, of course, in the public domain, free for anyone to write about. In order to provide Eight Men Out with copyright protection and to serve as a ready tell upon plagiarism of his book, Asinof was advised to insert original and identifiable author-created content into his story. One of the components unique to Eight Men Out would take the form of fictional characters.

In Bleeding, a conversation between Asinof and a television executive named Diana Kerew indicates that Asinof placed two fictional characters in Eight Men Out. One of these characters has been exposed; the other remains a matter of speculation. There is no dispute regarding the identity of Fictional Character #1. He is Harry F., the memorable thug “with a bored, raspy voice” who intimidates Lefty Williams into his first-inning blow-up in Game Eight. See Eight Men Out, 113-114. In a late-life interview, Asinof described Harry F. as “a dash of fiction” designed to substantiate unauthorized use of his work. See again, Gene Carney, Burying the Black Sox, 204-205. Whether or not Williams (or his wife) was threatened prior to Game Eight is probably unknowable. The evidence is slim, circumstantial, and cuts both ways. But whatever the case, Harry F. or a Harry F.-type character has become an indelible part of the Black Sox saga, incorporated into the Sayles film, and other post-Eight Men Out accounts of the Black Sox scandal.

B. Invented Dialogue: A far-larger problem for Asinof than that posed by potential plagiarists was his lack of inside scandal info. Of the flesh-and-blood Eight Men Out, four (Joe Jackson, Fred McMullin, Buck Weaver, and Lefty Williams) were already dead by the time Asinof began his Eight Men Out research, while three (Eddie Cicotte, Chick Gandil, and Swede Risberg) refused to speak to him about the fix. The only player source left to Asinof was Happy Felsch, an amiable dunce who never fully understood the conspiracy that he had joined or knew much about those who were supposed to finance the World Series fix.

Worse yet was the situation with fix gamblers. Already middle-aged men in 1919, the gambler ranks had been reduced to one survivor by 1960: ancient Abe Attell, an engaging but incorrigible rogue not overly fussy about the truth. With a grain of salt that grew larger as the project continued, Asinof would use Attell as a resource for providing readers with a take on the gambler action — first in a ghost-written Cavalier Magazine expóse in 1961 and then in Eight Men Out two years later. But Abe Attell was only one actor in a multi-faceted conspiracy that involved many. And the most important gamblers — Arnold Rothstein, Sport Sullivan, Nat Evans, David Zelcer, Carl Zork — were not only long-dead; they had been tightlipped about the Series fix when alive.

To remedy the situation, particularly as it pertained to private conversations to which informants Felsch and Attell had not been a party, Asinof would employ literary license. Readers would be informed of what non-cooperating or dead-and-silent characters MIGHT have said. As a result, the pages of Eight Men Out crackle with riveting dialogue, largely courtesy of the imaginative powers of its author. Below is a non-exhaustive list of Eight Men Out conversations for which Asinof had no known first-person source.

1. Page 17: Chick Gandil-Swede Risberg locker room conversation supposedly overheard by White Sox utility infielder Fred McMullin that served as McMullin’s entrée into the fix. Note: According to the grand jury testimony of Eddie Cicotte, McMullin was actually one of the fix instigators.

2. Page 30: Arnold Rothstein-Sport Sullivan conversation at the Rothstein residence on September 26, 1919.

3. Page 30: Follow-up telephone call by Rothstein to Nat Evans.

4. Page 34: Quotes attributed to Sullivan and “Brown” during a player-gambler fix meeting at the Warner Hotel in Chicago.

5. Page 35: Telephone conversation between Rothstein and oil tycoon Harry Sinclair about the teams playing in the 1919 Series.

6. Page 35: Rothstein exchange with gambler Nick “The Greek” Dandolis.

7. Page 37: Sullivan-Gandil dialogue attending the delivery of $10,000 of the fix payoff.

8. Page 71: Conversation between White Sox manager Kid Gleason and his wife at the entrance of the Sinton Hotel on the eve of Game One.

9. Page 100: Conversation between Sullivan and (perhaps fictional) Chicago gambler Pete Manlis about Series betting.

10. Page 113: Rothstein-Sullivan conversation about the fix after Game Seven.

11. Pages 113-114: Telephone conversation between Sullivan and fictional thug Harry F.

12. Pages 116-117: Invented exchange between Lefty Williams and Harry F. on the evening before Game Eight.

13. Pages 128-129: Recount details of a private conversation about Series fix ramifications between White Sox club owner Charles Comiskey and White Sox corporation counsel Alfred Austrian.

14. Page 130: Conversation between Comiskey and Cook County State’s Attorney Maclay Hoyne in Hoyne’s office.

15. Page 137: Telephone call by Comiskey to White Sox catcher Ray Schalk to discourage further talk of a Series fix.

16. Page 161: Private discussion between Comiskey and Alfred Austrian about the probe of the World Series being conducted by the grand jury.

17. Page 167: Exchange between Buck Weaver and an antagonistic patron in a Detroit tavern.

18. Page 217: Three-way conversation involving Austrian, Rothstein, and attorney William J. Fallon in the Austrian law office in Chicago on October 26. [Note: On that date, Fallon was in a Manhattan courtroom to oppose a prosecution motion for postponement in the Arnstein conspiracy/war bond theft case.]

C. Manufactured Events: Two events central to the Black Sox Scandal as Asinof depicts it never happened. Reputed behind-the-scenes defense strategist William J. Fallon did not accompany Arnold Rothstein into the grand jury room. Indeed, Fallon was not even in Chicago on that date. As reflected in the newspaper reportage cited in Part 1, Nos. 49 and 50, above, Rothstein was attended by attorney Hyman Turchin during his trip to Chicago. Fallon, meanwhile, was handling a pretrial motion in the Nicky Arnstein case in a Manhattan courtroom. Rothstein’s Chicago adventures, at least as recounted in Eight Men Out, are contrived.

Unlike the real-life Rothstein and Fallon, the Eight Men Out character Harry F. is pure fiction, an Asinof literary creation with a copyright protection objective. As previously noted, the evidence of a pre-Game Eight threat directed at Lefty Williams is thin and contradictory. But one thing is certain, if Williams was threatened, it was not by the fictional Harry F.

Joseph “Sport” Sullivan is perhaps the most shadowy of the major characters involved in the Black Sox Scandal. The Boston-based gambler had a nationwide reputation for baseball betting and prognostication, and was a prominent figure at World Series games beginning in 1903. He began fixing sporting events long before the 1919 World Series and was arrested at least six times for gambling-related offenses. (BOSTON HERALD)

PART III: ASINOF AND THE NARRATIVE OMNISCIENCE OF EIGHT MEN OUT

One of the signature features of Eight Men Out is its penetration of the minds of its characters. No private thought is left undisclosed to the reader. And this is accomplished despite the fact that Eliot Asinof never met most of the men involved in the corruption of the 1919 World Series, much less put them on his couch. Samples of mind-reading by Asinof include the following:

1. Page 9: Sport Sullivan’s thoughts after Chick Gandil proposed fixing the 1919 World Series.

2. Page 35: Nat Evans “approved” of the Rothstein plan to place $40,000 in the safe of the Congress Hotel and “anticipated no trouble doing that in Chicago.”

3. Page 35: Chick Gandil’s “apprehensions were growing” and the strain of the fix plan led to “annoying stomach pains, not at all typical of him.”

4. Page 36: Sullivan “was surprised” when Evans gave him $40,000, because Sullivan “never actually believed” the fix plan “would reach this point.”

5. Page 37: Sullivan was “far from delighted” by the prospect of meeting Gandil with only $10,000 of the payoff.

6. Page 43: Gandil had to place his own Series bets with a “second-rate gambler he knew, fully aware that such a tactic only added to the possible exposure of the fix.”

7. Page 44: During the Sinton Hotel fix meeting, “the ballplayers had spoken the words of their own complicity, but they did not actually believe in them.”

8. Page 44: “Gandil was worried” after the Sinton Hotel fix meeting.

9. Page 48: Provides thoughts of Black Sox before Game One and the basis for their nonchalance about agreeing to the Series fix: “If all this bothered the eight ballplayers, they didn’t show it. … They weren’t going to get stirred up about the fixed ball game they were about to play, even if they got swindled out of the money.”

10. Page 65: As he warmed up to begin the fourth inning, Eddie Cicotte “didn’t want any trouble from [catcher Ray] Schalk now.”

11. Page 66. After a circus catch by co-conspirator Happy Felsch in center field, Cicotte knew “how right he had been” to suspect that the other Black Sox would “dump [all the responsibility for losing Game One] on him.”

12. Page 68: Cincinnati school children “wondered why the score to complete the fourth inning was taking so long” to be posted on their inning-by-inning World Series bulletin boards.

13. Page 78. On the morning of Game Two, “Gandil woke with the same thought he had taken to sleep: Where the hell was Sport Sullivan?”

14. Page 81: “The Cincinnati ballplayers themselves were a little stunned by their previous day’s victory [in Game One].”

15. Page 83: As he readied to pitch Game Two, Lefty “Williams had one thing on his mind. How could he lose this game without looking bad?”

16. Page 92: Following the $10,000 fix payoff shortchange delivered by Bill Burns after Game Two, “Gandil began thinking how he, too, could play the [shortchange] game.”

17. Page 95: “Gandil had lied [about Black Sox intentions for Game Three]. If he could, he was going to make Burns and Attell sweat. And he was going to force Sport Sullivan out of the woodwork.”

18. Page 100: After informing Arnold Rothstein about the status of the Series fix in the lobby of the Ansonia Hotel, “Sullivan left the meeting elated. He had carried it off well and Rothstein seemed pleased.”

19. Page 100. Sullivan’s “elation” was quickly doused; he felt “threatened” by a hotel front desk conversation with gambler Pete Manlis about Series betting.

20. Page 112: After the White Sox victory in Game Seven, “Arnold Rothstein was also worried. He did not have to remind himself how little he had liked the whole scheme from the beginning. His qualms had persisted. Too many people involved.”

21. Page 113: Sullivan “saw now how badly he’d handled the whole thing. He had lost control of the players, having taken too much for granted.”

22. Page 114: As he took the mound to begin Game Eight after being threatened by Harry F., “Lefty Williams thought of himself as a decorous man, very good at his job, well liked by those who knew him and worked with him. But Lefty Williams was in trouble. In all his life, he never dreamed that anything like this could happen to him. It seemed so fantastic that even the fact that it was all very logical meant little to him.”

23. Page 125: Reveals what Gandil is thinking privately when Sullivan finally delivers $40,000 of the promised payoff money to him, Swede Risberg, and Fred McMullin at the Warner Hotel.

24. Page 125: White Sox corporation counsel Alfred Austrian’s thoughts and attitudes are exposed. Austrian “could understand [club owner Charles] Comiskey’s rather highhanded tactics with players’ salaries.” Regarding the grand jury investigation, “To Austrian, there seemed to be little danger to his client’s interests. At least, at this time. If there had been a sellout, as Comiskey so strongly indicated, Austrian was not going to argue the point!”

25. Page 129: Comiskey “was taken by [an Austrian] proposal” to initiate his own investigation of Series fix rumors.

26. Page 136: Arnold Rothstein “noted the lack of action [to investigate Series fix rumors by baseball executives] with a sense of relief. It reaffirmed his sense of order, all these big millionaires running the baseball world were like a squawling bunch of idiot kids. He felt he could walk all over them. They were just like politicians; they would end up working for him, …”

27. Page 166: “Sometimes [Buck] Weaver wondered how other clubs ever beat the Sox. There were other times when he wondered how the White Sox ever managed to get through nine innings together.”

28. Page 180: Goes inside head of White Sox club secretary Harry Grabiner as Comiskey reads a telegram from Billy Maharg.

29. Page 180: “Kid Gleason looked at [Comiskey] and felt frightened for himself. There was something so monstrous about this [fix rumor] business, he sensed his inability to cope with it.”

30. Page 192: After interviewing Happy Felsch, Chicago Evening American reporter “Harry Reutlinger was moved. How much of Felsch’s story was honest and accurate, he had no idea. What evoked his admiration was the genuine remorse and lack of self-pity. Felsch was guilty, yet he had pride in himself.”

31. Page 234: Fugitive gambler defendant Bill “Burns’ ” first reaction [to the offer to turn State’s evidence in return for immunity] was to cringe. He feared reprisal from gamblers. The world of stool pigeons was an eerie one. [AL president Ban] Johnson had to smile: And what was the world of a fugitive from justice, a paradise?”

32. Page 253: At the criminal trial, “Joe Jackson sat through [the testimony of Bill Burns] like a kid listening to a fascinating story he had never heard before. Somehow he’d assumed that it was the gamblers who had started it all.”

EIGHT MEN OUT: THE 1988 FILM BY JOHN SAYLES

Recitation of instances where the Sayles film faithfully reproduces an already noted Asinof fact error or incorporates Asinof’s invented dialogue and made-up events is redundant. The following list is confined to errata that Sayles injected into the film version of Eight Men Out entirely on his own. The non-exhaustive roster includes:

PART I: FACTUAL ERRORS CONTAINED IN THE 1988 SAYLES FILM

1. In its very first baseball scene, the film depicts lefty-batting Eddie Collins hitting from the right-hand side of the batter’s box. Seconds later and against a St. Louis Browns right-handed pitcher, switch-hitter Buck Weaver also bats righty. Facts: For the ways that the two players actually batted, see the Baseball-Reference entries for Collins and Weaver.

2. After the Sox defeat the Browns to clinch the 1919 pennant, their bonus for the achievement from club owner Comiskey was a case of flat champagne. Fact: The impetus of this phony scene is likely Chick Gandil’s notoriously unreliable 1956 Sports Illustrated article which stated: “I recall only one act of generosity on Comiskey’s part. After we won the World Series in 1917, he splurged on a case of champagne.” To fit his portrayal of movie villain Comiskey as a “cheap bastard,” Sayles moved the event to 1919, made the champagne flat, and presented it as a substitute for (fictional) cash bonuses promised the Sox players for winning the 1919 AL pennant.

3. Swede Risberg is portrayed throughout the film as Gandil’s co-partner in the effort to recruit Cicotte and other Sox players as fix participants. Fact: As reflected in the grand jury testimony of Cicotte himself and the trial testimony of Bill Burns, Cicotte and Gandil were the fix architects, with Fred McMullin also active in the player recruitment process. Risberg, while an enthusiastic fix participant, was not a significant actor in putting the fix together.

4. The film has Joe Jackson recruited to join the fix by Swede Risberg. Fact: Jackson told the grand jury that he did not attend any World Series fix meetings and was recruited privately by Chick Gandil, not Risberg. See JGJ 5-7 to 13; JGJ 7-13 to 24.

5. Presumably to economize on characters, the film has fellow Chicago sportswriter Ring Lardner serve as Hugh Fullerton’s partner in circling suspicious World Series plays on their scorecards: Fact: Joining Fullerton in this exercise was New York Times special correspondent Christy Mathewson, not Lardner. See Carney, Burying the Black Sox, 78.

6. Just before Game One begins, the film places fix gamblers Bill Burns and Billy Maharg settling into their seats at Redland Field. Fact: Neither Burns nor Maharg attended Game One. See Rob Edelman, “For the Record: The Movies, Eight Men Out, and Historical Accuracy,” Base Ball: A Journal of the Early Game, Vol. 6, No. 1, Spring 2012, 103.

7. Prior to Game One, manager Gleason spots a withdrawn Joe Jackson seated alone in the dugout. When Gleason speaks to him, Jackson tells his manger that he does not want to play. An astonished and angry Gleason thereupon orders Jackson to take the field. Facts: Jackson told a variety of unlikely and irreconcilable stories about his involvement in the Series fix. The one that Sayles chose to present as fact is a variant of the implausible narrative that Jackson unveiled in 1949. In same, Jackson maintained that he was so distraught by rampant pre-Series fix rumors that he went to club owner Comiskey’s hotel room on the night before Game One and begged to be kept out of the lineup, lest his reputation be besmirched by playing in a rigged game. See “This Is the Truth,” by Shoeless Joe Jackson as told to Furman Bisher, Sport, October 1949. Interestingly, between his September 1920 grand jury confession of fix complicity and this story, Jackson contended that he had been unaware of the fix while the Series was ongoing and had only been informed of it after Game Eight was played. See e.g., the April 1923 civil trial deposition of Joe Jackson, as quoted verbatim by friendly sportswriter Frank G. Menke in the Lincoln (Nebraska) Star, April 23, 1923, and elsewhere.

8. In his DVD interview, screenwriter/director Sayles states that he had the play-by-play of each 1919 World Series game. So, after Eddie Cicotte signals that the fix is on by hitting Reds leadoff batter Morrie Rath with the second pitch of Game One, the film demonstrates Buck Weaver’s innocence of fix involvement by having him making a diving grab of a hot shot to third and throwing a strike to scowling first baseman Chick Gandil for the putout. Fact: Jake Daubert, the Reds second batter, singled to right-center, sending Rath third whence he scored on a sacrifice fly hit by next Reds batter Heinie Groh, as per the Game One scorecard that Sayles had in his possession while making Eight Men Out. For a more accessible batter-by-batter account of the game, see William A. Cook, The 1919 World Series: What Really Happened? (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2001), 17-26.

9. The film has Cicotte removed by manager Gleason from Game One after surrendering a fourth-inning triple to Reds pitcher Dutch Ruether. Fact: Cicotte remained on the mound after the Ruether three-bagger and was not yanked until after he had yielded the singles to Morrie Rath and Jake Daubert that stretched the Reds lead to 5-1, See Cook, The 1919 World Series, 21-22.

10. Sayles has Fred McMullin delivering a fix payoff to Joe Jackson in his hotel room following Game One. Jackson, meanwhile, is depicted as depressed by his participation in the fix and indifferent to the money. Facts: The lone fix payoff made to Jackson ($5,000 of a promised $20,000) was delivered by Lefty Williams (not McMullin) the evening before the Sox left for Cincinnati to play Game Five (not after Game One). See JGJ 5-14 to JGJ 6-14. See also, grand jury testimony of Claude Williams, September 29, 1920, WGJ 26-30 to WGJ 27-26. And Jackson was far from indifferent about the money, having quizzed Gandil about non-delivery of expected payoff installments after Game One, Game Two, and Game Three. See JGJ 9-24 to JGJ 10-18. Jackson was still rankled about the shortfall in his promised fix payoff a year later, complaining about it to the press following his grand jury testimony, as reported in the Chicago Journal, Chicago Tribune, Cincinnati Post, and elsewhere, September 29, 1920.

11. In the film, Dickey Kerr, the White Sox starting pitcher and shutout winner in Game Three, is depicted as a right-handed pitcher. Fact: The undersized Kerr was a lefty. See Dickey Kerr’s SABR BioProject article by Adrian Marcewicz.

12. As Kerr warms up for Game Three, he recalls the first major league game he ever attended: a no-hitter thrown by now-manager Kid Gleason in a victory over the celebrated Cy Young: Fact: Kerr was 2 years old when Gleason quit pitching in 1895, and Gleason never threw a no-hitter against Young (or anyone else) during his big leagues career. See Edelman, “For the Record,” 102-103.

13. Sayles has the actress portraying Lefty Williams’s wife (Nancy Travis) speak in a decided Southern accent. Fact: Utah-born and raised Lyria Wilson Williams was not a Southerner and did not speak in a Southern accent. For more, see Jacob Pomrenke, “Lyria Williams, Wife of a Baseball Exile,” SABR Black Sox Scandal Research Committee newsletter, Vol. 10, No. 2, (December 2018), 15-21.

14. The film portrays the fix being exposed in the almost-immediate aftermath of Game Eight. Facts: Apart from a handful of Hugh Fullerton columns and a few by others, Series fix rumors were largely ignored by the sporting press and by baseball fans. The 1920 baseball season was played by the Black Sox players (except Gandil who refused his 1920 contract offer), and no Series-related investigative action was undertaken by the Cook County grand jury until September 22, 1920. See Lamb, Black Sox in the Courtroom, 37-47.

15. In a crowded barroom, Happy Felsch admits his involvement in the Series fix and jokes about it with fellow patrons. Facts: A seemingly contrite Felsch confessed his fix involvement to Chicago newsman Harry Reutlinger while being interviewed privately at the Felsch apartment. See the Chicago Evening American, September 30, 1920.

16. Sometime after the World Series, Sayles has Chicago newsmen Hugh Fullerton and Ring Lardner eavesdropping on a barroom conversation in which an inebriated Abe Attell talks about the Series fix. Fact: Fullerton was not involved. The Attell barroom admissions were overheard by Chicago Tribune reporter James Crusinberry and Lardner. See the accounts of the Crusinberry grand jury testimony published in the Chicago Journal, September 22, 1920, and Chicago Evening American and Los Angeles Times, September 23, 1920, and Crusinberry’s first-person account in Sports Illustrated on September 17, 1956.

Author’s note: The Sayles portrayal of Black Sox-related legal proceedings is a farce, with imaginary events and/or preposterous courtroom scenes pervading the final third of the film. The entirely invented matters are specified below. The ensuing points are confined to the legal proceedings-related facts that Sayles got wrong or misrepresented.

17. Both the book and film versions of Eight Men Out assert that legal representation of the Black Sox players was arranged by Charles Comiskey. In Bleeding Between the Lines, Eliot Asinof revealed that this plot development was inspired by a conversation he had with trial judge Hugo Friend some 40 years after-the-fact. Friend offered no proof, but speculated that the high-priced lawyers who represented the accused ball players must have been paid by Comiskey. Facts: In the almost 60 years that have elapsed since the Friend-Asinof conversation, not an iota of actual proof has been discovered to substantiate Friend’s speculation. It would also seem irreconcilable with White Sox corporation counsel Alfred Austrian’s public endorsement of the grand jury’s already revealed intention to indict the Black Sox. The Austrian commentary was timely and crucial to public validation of any grand jury true bills, being delivered in response to prosecutor Maclay Hoyne’s opinion that no indictable offense had been committed, only piddling misdemeanors, and that the probe should be discontinued. See the Chicago Tribune and New York Times, October 1, 1920, for Austrian’s tutorial on the statutory justification for the indictable offenses under consideration by the grand jury. In the wake of Austrian’s rebuke, and those of Judge McDonald and grand jury foreman Brigham, as well, Hoyne (the lame-duck State’s Attorney who had been absent and on vacation) promptly backed off and permitted the grand jury to resume its inquiries without further interference. See Lamb, Black Sox in the Courtroom, 66-68.

18. In pretrial conferences with their lawyers and in the courtroom, all eight Black Sox player defendants are depicted as present. Fact: Los Angeles resident Fred McMullin did not arrive in Chicago until after jury selection had already commenced. The charges against McMullin, therefore, had to be severed from those against the other seven White Sox players and deferred for trial at a later date, as subsequently reported in the Chicago Evening Post, Washington Post, and others on August 4, 1921. McMullin never sat in pretrial conference with his codefendants or set foot inside the trial courtroom.

19. In pretrial conferences and in the courtroom, the Sayles film presents only eight defendants (including the absent Fred McMullin). Fact: In the Black Sox case, 11 defendants stood trial: seven accused White Sox players, plus gambler defendants David Zelcer, Carl Zork, Ben Levi, and Lou Levi. See Lamb, Black Sox in the Courtroom, 101-148.

20. As the trial begins, Hugh Fullerton comments that the prosecution has “three signed confessions” to use against the accused. Fact: As explained in the Asinof section above, there were no “signed confessions” in the Black Sox case.

21. The closing cast credits list Ban Johnson and John Heydler among the baseball club owners portrayed in the film. Fact: Neither man was a club owner. Johnson was President of the American League, while Heydler was National League President.

PART II: FICTIONAL CHARACTERS AND INVENTED SCENES IN THE SAYLES FILM

1. As a vehicle for the film’s portrayal of Buck Weaver as a non-fix participant wrongly accused, Sayles’s opening scene introduces Scooter and Bucky, the fictional Chicago street urchins who will later serve as sounding board for Weaver professions of innocence.

2. As the pennant-clinching White Sox win over the Browns unfolds in late September, Sayles has gamblers Bill Burns and Billy Maharg seated in Comiskey Park, discussing the amenity of various Chicago players to their fix proposition. Fact: This never happened.

3. A linchpin of the film’s sympathetic treatment of fix conspirator Eddie Cicotte is a scene set late in the 1919 season wherein club boss Comiskey holds 29-game winner Cicotte to the letter of their purported 30-win bonus agreement. Immediately thereafter, Cicotte joins the Series fix conspiracy. Facts: No such meeting between Cicotte and Comiskey ever occurred, as the 30-win bonus on which the event is premised is apocryphal. See again, Carney, Burying the Black Sox, 193-198, and Hoie, “1919 Baseball Salaries,” 29-30. And by the time of the purported Cicotte-Comiskey meeting, Cicotte and Chick Gandil already had put the Series fix plan in motion.

4. After a sterling Weaver fielding play in the Series, Swede Risberg accuses Buck of reneging on a commitment to participate in the fix. Fact: No historical evidence of an on-field Weaver-Risberg confrontation exists.

5. When Bill Burns and Billy Maharg come to the Attell hotel room following Game Two to pick up the players’ payoff money, Attell cohort Bennett (David Zelcer) threatens the pair with a handgun, pointing it directly at Burns. Fact: In their trial testimony and subsequent civil depositions, Burns and Maharg recount the details of their visit to the Attell hotel room. No mention is made of their being threatened by a gun-pointing Attell associate because it never happened.

6. As rumors of White Sox corruption swirl after Game Five, Buck Weaver tells Scooter, Bucky, and other kids that he (Weaver) has to stand up for his teammates during troubled times. Fact: Given that the street kids are a Sayles creation, no such encounter could have happened in real life.

7. To deliver the threat to lose Game Eight to Lefty Williams, the film interposes New York City thug Monk Eastman between Sport Sullivan and the film’s unnamed Harry F.-type character, and thereafter puts Eastman in Comiskey Park to observe Game Eight. Fact: Unlike the make-believe Harry F., Eastman was a real-life gangster. There is no historical evidence, however, that Eastman was in any way connected to the fix of the 1919 World Series or that he was in Chicago for Game Eight. Such events resided only in Sayles’s imagination.

8. After the White Sox loss in Game Eight, the film has Kid Gleason and Weaver engaged in a locker room conversation in which Gleason bares his affection for Weaver and states his belief that Buck was not involved in the Series fix. Fact: No historical evidence of such a locker room conversation exists.

9. During a pretrial conference of Black Sox defendants and lawyers assembled by White Sox corporation counsel Alfred Austrian, Buck Weaver angrily demands to know who is paying for the defense lawyers. Austrian, who does almost all of the talking at the meeting, then tells Weaver that in a conspiracy case, the less those accused know, the better. Facts: The pretrial conference is a Sayles fabrication for which utterly no historical support exists. Moreover, the very notion of such a meeting or that the able and experienced criminal defense attorneys supposedly at the meeting would have sat silent and let a corporate lawyer dictate their defense strategy borders on laughable. There is simply no evidence that Austrian had any contact whatever with the Black Sox accused (or their lawyers) once Lefty Williams had made his grand jury appearance on September 29, 1920.

10. As the Black Sox trial opens and during proceedings thereafter, Sayles places baseball commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis in the courtroom gallery to observe the proceedings firsthand. Facts: For the first two years of his commissionership, Landis remained a sitting federal district court judge with a full calendar of his own cases. On the date that the Black Sox case went to the jury, for example, Landis was engaged in the arraignment of defendants taken into custody on federal mail robbery charges. See e.g., “Arrest Alleged Head of Mail Robbery Gang,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, August 2, 1921; “Round Up 26 Indicted in Mail Thefts,” Rockford (Illinois) Republic, August 2, 1921. Simultaneous to the Black Sox trial, Landis was also busy working on a ruling in a sticky labor dispute between local builders and construction unions that he had agreed to arbitrate. See “Judge Landis Issues Set of Business Tenets,” Wilkes-Barre (Pennsylvania) Times-Leader, and “Landis Issues Labor Tenets” (Cheyenne) Wyoming State Tribune, August 2, 1921. In reality, Landis never set foot inside Cook County Courthouse during the Black Sox case. But he did keep abreast of its courtroom developments via daily delivery of a trial transcript to his chambers in the federal courthouse, as reported in the Chicago Evening Post, August 3, 1921.

11. During defense cross examination of Billy Maharg, gathered press and courtroom spectators are stunned by prosecutors’ revelation that the player confessions have been stolen, the unstated implication being that as a consequence, the jury will never hear the confession evidence. This, in turn, allows disillusioned newsmen Hugh Fullerton and Ring Lardner to reaffirm aloud their suspicion that the trial’s outcome has been prearranged and that Not Guilty verdicts are assured for the Black Sox. Facts: As the historical record establishes, the missing confessions were old news by the time that Maharg took the witness stand on July 27, 1921. More than seven months earlier, the theft of grand jury testimony and other evidence had been publicly revealed and widely reported in the press. See e.g., the Boston Globe, Chicago Tribune, and Washington Post, December 8, 1920. Left unmentioned by filmmaker Sayles is the fact that the missing transcripts of the Cicotte, Jackson, and Williams grand jury testimony had been recreated well in advance of trial and deemed admissible in evidence by Judge Friend. And by the time that Maharg testified, the jury had already heard the Cicotte, Jackson, and Williams grand jury testimony at length, as reported in the Chicago Herald-Examiner, Chicago Tribune, Savannah Daily News, and elsewhere, July 26, 1921, and even acknowledged by Eliot Asinof in the book version of Eight Men Out, 257-260.

12. During the defense case, Buck Weaver jumps up and announces his displeasure with defense counsel, his frustration with their decision not to have the defendants testify, his desire to have a separate trial, and the like, only to be threatened with contempt by Judge Friend for the outburst. Fact: As reflected in extensive press coverage of the proceedings, Weaver did not utter an audible word during the course of the trial. Like much else in the film’s depiction of alleged trial events, the incident never happened.

13. After explaining what might lead a previously honest ballplayer astray, the cinematic Kid Gleason delivers a glowing testimonial to the 1919 Chicago White Sox that evokes a standing ovation from the courthouse gallery. Facts: As reflected in the trial reportage of the Chicago Tribune and New York Times, July 29, 1921, the brief appearance of Gleason and several Clean Sox on the witness stand was intended to cast doubt on Bill Burns’ account of the Sinton Hotel gambler-player fix meeting. Press failure to mention the film’s Gleason testimonial and gallery ovation is not surprising. Those things never happened.

14. After the jury has been returned to the courtroom to deliver its verdict but before same is announced, Judge Friend declares that if anyone in the courtroom wants to make a statement, now is the time. At this, Buck Weaver rises to protest his innocence, complain about his not being able to testify, etc. Facts: No speeches are sought or permitted once a deliberating jury has returned to the courtroom to deliver its verdict. The pre-verdict Weaver soliloquy is pure Sayles fantasy, and a ludicrous one at that.

15. The film’s final scene has the banished Buck Weaver watching from the seats while the exiled Joe Jackson, playing under the alias Brown, slams a triple for a semipro team from Hoboken, New Jersey. Facts: As Eight Men Out screenwriter/director Sayles himself admits in an interview contained on the 20th anniversary DVD, the scene is entirely imaginary.

To go back to the Eight Myths Out page, click here.