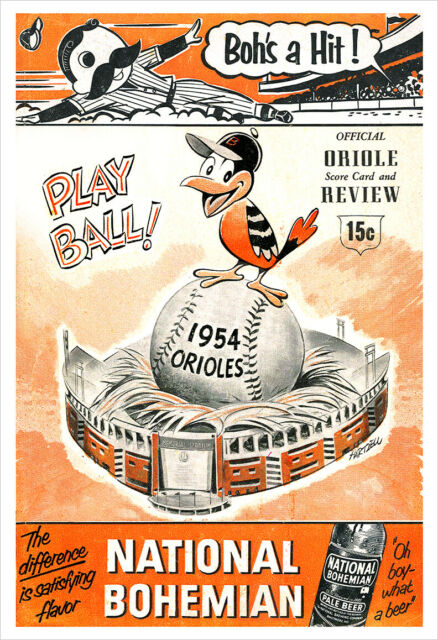

April 15, 1954: Orioles return to Baltimore after 52 years

The streets of Baltimore were jam-packed with an estimated 350,000 baseball fans who warmly welcomed (at least in name) their Orioles home. “A wonderful, wonderful parade!” exclaimed one fan, Blanche McGraw.1 She was the widow of John McGraw, the longtime New York Giants manager whom old-timers would tell you was first a star on the diamond with the original Orioles of the 1890s. Baltimore cherished its rich baseball heritage, which included native son Babe Ruth, but had suffered a huge void for over half a century. The old Orioles left Baltimore for New York after the 1902 season and later became known as the Yankees. Except for the brief Federal League era, Baltimore became a minor-league town. However, the St. Louis Browns, usually the doormat of the American League, were given new life and moved east to become the new Orioles in 1954.

The streets of Baltimore were jam-packed with an estimated 350,000 baseball fans who warmly welcomed (at least in name) their Orioles home. “A wonderful, wonderful parade!” exclaimed one fan, Blanche McGraw.1 She was the widow of John McGraw, the longtime New York Giants manager whom old-timers would tell you was first a star on the diamond with the original Orioles of the 1890s. Baltimore cherished its rich baseball heritage, which included native son Babe Ruth, but had suffered a huge void for over half a century. The old Orioles left Baltimore for New York after the 1902 season and later became known as the Yankees. Except for the brief Federal League era, Baltimore became a minor-league town. However, the St. Louis Browns, usually the doormat of the American League, were given new life and moved east to become the new Orioles in 1954.

As the parade wound down, rain began to fall, complicating the traffic situation. But who cared? “To Baltimore baseball fans,” wrote Patrick Skene Catling of the Baltimore Sun, “it was the parade of the century.”2 With streets being closed for the parade, some fans parked three-quarters of a mile away and walked in the rain.3 It was a “bleak and blustery afternoon,” according to Lou Hatter of the Baltimore Sun, who nevertheless added that it was a “never-to-be forgotten day in the sports history of Baltimore.”4

Vice President Richard Nixon had no trouble arriving to throw out the ceremonial first pitch. “This is a great day for baseball and a great day for Baltimore,” he said.5 Memorial Stadium, home to the International League Orioles, had received a $6.5 million upgrade, yet was still lacking in amenities at game time. Both the team and the ballpark were works in progress. “There was still some wooden scaffolding covering uncompleted brick facing around the outside of the park,” wrote Herb Heft in The Sporting News. “Only six of the nine runways connecting upper stands with the lower were in operation, and some of the approaches to the turnstiles were still unpaved. However, every seat was in place, the grass was a lush green, the infield smooth, and the baseball-hungry fans of Baltimore, impatient for deliverance from the minor leagues after more than half a century, were all too happy to forgive any slight inconvenience.”6

The Orioles hoped for a fresh start and distance between themselves and the disheartening history of the Browns. A charter member of the American League in 1901 (actually spending their first year in Milwaukee), the Browns had only 12 winning seasons in their history and one pennant, during the World War II years when replacement players donned major-league uniforms. St. Louis could boast of two major-league franchises for half a century, but the Cardinals always outshone the Browns, and fans in Baltimore dreamed of the day when they could just have a team again. Baltimore supported their Triple-A minor-league Orioles yet longed to see major-league stars again. While the Braves, Athletics, Dodgers, and Giants moved west during the 1950s, taking their team names and identities with them, the 54-100 Browns moved east, and the Orioles were born.

The Orioles had split their first two games in Detroit. Bob Turley was given this historic home opener for the Orioles. The 23-year-old right-hander had finished 2-6 with a 3.28 ERA in 10 appearances with the Browns at the end of his rookie season of 1953. Turley later won both a Cy Young Award and World Series MVP, but those honors did not come while he was wearing an Orioles uniform. Turley was opposed by the 37-year-old veteran Virgil Trucks. Trucks was a household name throughout baseball, having won 20 games in 1953, a season split between the Chicago White Sox and the Browns. This was the eighth time in 11 seasons that Trucks reached double-digit wins, and his strikeout totals frequently ranked in the top 10 of American League pitchers. Throwing a shutout was always a possibility: He threw 33 of them in his career.

The White Sox had been in contention for the AL pennant in the early part of 1953, but despite an 89-65 record were 11½ games behind the Yankees. The White Sox of the 1950s had strong teams but were always looking up at the Yankees until they finally got to the World Series in 1959. The White Sox had lost their first two games of this season to the visiting Indians.

Eddie Rommel umpired at home plate while Larry Napp (first base), Red Flaherty (second), and Johnny Stevens (third) worked the bases.

Turley surrendered a leadoff single to Chico Carrasquel and walked Bob Boyd. With two out, Ferris Fain lofted a foul pop to left. Sam Mele chased it down and made the catch, leaping into the Opening Day red, white, and blue bunting. Both teams were scoreless after one inning. The White Sox put runners on again in the second with singles by Sherm Lollar and Johnny Groth. Turley came back to shut the door by striking out Trucks and Carrasquel.

The first run in the history of Memorial Stadium happened in the third when Orioles catcher Clint Courtney launched a home run to right. “The grinning, bespectacled ‘toy bulldog,’” Lou Hatter of the Baltimore Sun said of Courtney, “circled the bases with Baltimore’s first American League home run in 52 seasons.”7 The Orioles went on to load the bases on a single and two walks. Mele hit a screaming grounder to short, where Minnie Miñoso leaped to his left, made the stop, and threw to second for the force out, preventing further damage.

Vern Stephens had a power surge as well and lined a home run to left into “the eager grasp of the cheering bleacherites near the ‘Good Luck Birds’ sign on a supplementary scoreboard — near the 380-foot marker,” wrote Hatter.8 The infant Orioles had a 2-0 lead after four innings.

The lead held until the top of the seventh. With two out, Carrasquel reached on an infield single and scampered to third on Nellie Fox’s single to right. Bob Boyd singled to center to score Carrasquel, but Miñoso struck out to end the inning. The White Sox had cut the lead to 2-1.

The Orioles had an immediate answer in their half of the seventh. Baltimore native Bobby Young doubled just inside the left-field line, driving Trucks to the showers. In from the bullpen came the lefty Billy Pierce, as Chicago manager Paul Richards was strategizing with three left-handed-batting Orioles due up. Pierce was a regular feature in the Chicago rotation. He won 18 the year before and started the All-Star Game for the American League. He also usually pitched a few innings of relief every year. The first lefty was Eddie Waitkus, who laid down a perfect bunt single along the third-base line, where the hustling Young ended up. Orioles manager Jimmy Dykes countered Richards‘ lefty-on-lefty strategy by sending up right-hander Don Lenhardt to hit for center fielder Gil Coan. Richards then came out to get Pierce and bring in right-hander Fritz Dorish. Lenhardt turned away from an inside pitch but inadvertently got the bat on the ball and tapped to second, where Fox threw out Young, who was caught in a rundown. Vic Wertz singled sharply to right and the Orioles scored the run anyway. Mele grounded into a double play to end the inning, but the Orioles led, 3-1.

Chuck Diering jogged in to play center field for the Orioles to start the top of the eighth. He closed the inning by catching a fly ball off the bat of Jim Rivera as the White Sox went down 1-2-3. The Orioles were also blanked in their half of the inning.

The White Sox started the ninth with two veteran left-handers being sent up to pinch-hit against Turley. Willard Marshall, batting for Groth, grounded out to short. Bud Stewart batted for the pitcher Dorish and lined to first, where a leaping catch by Waitkus “brought the house down.”9 Carrasquel and Fox both walked, putting the tying run on first in what the Sun’s Hatter called a “spine-tingling ninth.”10 Boyd grounded back to Turley, however, and the pitcher tossed him out to put the finishing touches on a historic day in Baltimore. “Delirium prevailed,” Hatter wrote.11

The Orioles played 3,005 more games at Memorial Stadium and won 1,686 more times before moving into the new Oriole Park at Camden Yards in 1992. The 46,354 fans there on April 15, 1954, witnessed the beginning of a new era in Baltimore baseball history. It was an event that was a half-century in the making.

Sources

Besides the sources mentioned in the Notes, the author relied on Retrosheet.org and Baseball-reference.com for information on the game.

Notes

1 Patrick Skene Catling, “The Parade,” Baltimore Sun, April 16, 1954: 1.

2 Catling.

3 Charles G. Whiteford, “Plane-Directed Traffic Plan Reduces Jams to Minimum,” Baltimore Sun, April 16, 1954: 1.

4 Lou Hatter, “The Game,” Baltimore Sun, April 16, 1954: 16.

5 John Van Camp, “Sun Is Happy Omen for Oriole Partisans,” Baltimore Sun, April 16, 1954: 1.

6 Herb Heft, “Baltimore Flips Lid — 500,000 at Parade, 46,354 See Game,” The Sporting News, April 21, 1954: 13.

7 Hatter.

8 Hatter.

9 Hatter.

10 Hatter.

11 Hatter.

Additional Stats

Baltimore Orioles 3

Chicago White Sox 1

Memorial Stadium

Baltimore, MD

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.