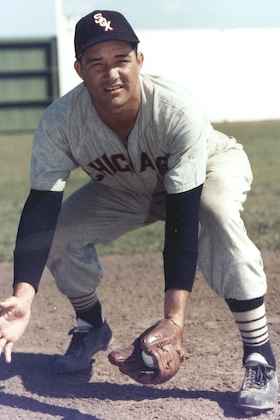

Chico Carrasquel

Alfonso “Chico” Carrasquel was the first great Hispanic defensive player in the major leagues. His play at shortstop made him as recognizable a big-leaguer as there was for several years. Carrasquel may not have revolutionized the position defensively like latter-day greats Ozzie Smith and Omar Vizquel – but he brought panache, born of his innate love for the sport and the excitement and joy he felt while on the baseball field. Some athletes, in the way they look or the way they play, are naturally appealing to the sports public at large. Carrasquel was one of them. From his minor league days, and for much of his time in the majors, the four-time All-Star was someone whom many people came to the ballpark with particular interest to watch.

Alfonso “Chico” Carrasquel was the first great Hispanic defensive player in the major leagues. His play at shortstop made him as recognizable a big-leaguer as there was for several years. Carrasquel may not have revolutionized the position defensively like latter-day greats Ozzie Smith and Omar Vizquel – but he brought panache, born of his innate love for the sport and the excitement and joy he felt while on the baseball field. Some athletes, in the way they look or the way they play, are naturally appealing to the sports public at large. Carrasquel was one of them. From his minor league days, and for much of his time in the majors, the four-time All-Star was someone whom many people came to the ballpark with particular interest to watch.

In Spanish-speaking nations outside of his home country, Carrasquel was known as El Gato de Venezuela because of his cat-like fielding movements. As sportswriter Ray Gillespie put it, “Chico has a natural talent for putting color into his tosses across the infield by using a graceful follow-through.” 1 His throws on double-play pivots also added flavor to the game, as Carrasquel said years after his retirement. He recalled that to avoid being spiked, “I was one of the first shortstops to throw the ball from second to first underhanded during double plays. Throwing the ball underhanded, the runner would have to slide or get hit with the ball.”2 Former teammate Minnie Miñoso recalled Carrasquel’s defensive brilliance in this manner: “I had seen so many good shortstops, but Chico played like no one I had ever seen. Gee whiz, this guy never misses a ball! What a glove. What hands. Perfect throw to first base all the time.”3

Alfonso Colón Carrasquel was born on January 23, 1926, in Caracas, Venezuela. He was one of 11 children and the first boy in the family of María Lourdes Carrasquel and her husband Cristóbal Colón. They lived in a canton of the capital city called Caserio Corao. Cristóbal worked as a laborer in a brewery in La Guaira, a town on the coast north of Caracas. María Lourdes supplemented the household income as a street vendor of home-cooked products such as arepas (corn cakes), which Alfonso also helped sell starting around the age of nine.

María Lourdes was the sister of pitcher Alejandro “Alex” Carrasquel, who became the very first Venezuelan in the majors in 1939. More than 300 have followed since – Alfonso was third overall after his uncle and Chucho Ramos. He was comfortable using his mother’s family name instead of his father’s – no doubt because of the repute associated with the name Carrasquel in Caracas. No other boy in all of Venezuela, outside of his own family, could say that he had an uncle who had played in the major leagues. Young Alfonso especially enjoyed listening to his uncle’s baseball reminiscences, involving some of the game’s greatest names. This was a source of pride for the boy, who (when not hustling around the neighborhood on behalf of his large family) was playing baseball.

Many members of Alfonso’s extended family also played professional baseball. His nephew, also named Cristóbal Colón, made it to the majors for 14 games with the Texas Rangers in 1992. Cris was a shortstop too. Two of Alfonso’s brothers, Domingo and Martín, played in the U.S. minors. So did his first cousin, Manuel Carrasquel, and three other nephews: Domingo and Emilio Carrasquel and Alfonso Collazo. Yet another nephew, Juan Muñoz, played briefly in Venezuela’s winter league, La Liga Venezolana del Béisbol Profesional (LVBP).

Alfonso was a sensation in junior league ball from the age of 17. He played (and also pitched) with various local clubs, including El Triunfo, La Vega, and the team of the city’s electric company, Electricidad de Caracas. When he was 19, he became a member of the team that represented Venezuela in the Amateur World Series of 1945. The following year, the country formed a professional league, which played its first season in the summer before switching to the winter. Carrasquel joined the Cervecería Caracas team. He played seven seasons with that club and eight more after it was rechristened as the Caracas Leones in 1952. He went on to play 21 total in his homeland.

In 1948, Fresco Thompson of the Brooklyn Dodgers signed Carrasquel to his first professional contract in the United States. The bonus was US$1,000. The scout traveled all the way to Caracas to secure the player. “I didn’t know where he [Carrasquel] lived,” Thompson said shortly after the signing. “The owner of the team didn’t have his address either. I had to wait around in my hotel room…until his team played again. We got along all right once he spelled out the name ‘Dodgers’ on my business card. That’s a universal word.”4

After winning the Venezuelan batting title with a .373 mark (in 118 at-bats), Carrasquel reported to spring training with the Dodgers at their “atomic-age” camp in Florida in 1949. The 23-year-old – who, like many players, took a couple of years off his age for professional purposes – made his way around Vero Beach with the help of Roy Campanella, who had picked up Spanish while playing ball in the Caribbean and Mexico. But when camp broke, Campanella headed with the team to Brooklyn, and Carrasquel was shipped to Triple-A Montreal before being transferred to the Dodgers’ Double-A team in Fort Worth. Shortstop was the wrong position for a Brooklyn prospect in the 1940s and ’50s because Pee Wee Reese was entrenched there.

Carrasquel, as did nearly all Hispanic players of the era, faced the challenge of a new language. Montreal manager Clay Hopper did not play him because he could not speak English. Slightly more than four decades after his rookie season, Carrasquel recalled, “I was very lonely that year. I would go to my hotel room and look at myself in the mirror and say: ‘Buenos días, Chico. Como estás?’ I had to talk to someone, and that someone was me. But I was determined to be a big league player. I wasn’t going to let anything stop me.”5

Carrasquel had a fine year with the bat at Fort Worth: a .315 batting average, with 6 homers and 69 RBIs. This end-of-season report delved further into the minor-leaguer’s potential: “Most of the experts believe the Cats possess by far the hottest prospect in Chico Carrasquel, who is called the league’s greatest postwar shortstop, and one of the finest to perform in the Texas League.”6 It was at Fort Worth, incidentally, that the infielder received the nickname “Chico” from teammates.

In October 1949, Frank Lane, general manager of the Chicago White Sox, obtained Carrasquel. The initial terms were $25,000 and two minor-league players.7 The deal was among the best of many by the man called “Trader Frank.” Just weeks after the exchange, John P. Carmichael of the Chicago Daily News wrote, “Lane is just as happy he got Carrasquel from Branch Rickey as if he’d taken Montreal’s Sam Jethroe, for whom the Braves paid $125,000.” Meanwhile, Rickey said, “It was a bad deal. It was a mistake.”8 The following year, renowned sportswriter Bob Broeg said, “Rickey reportedly has labeled [the trade] as his worst mistake.”9

The White Sox trained in Pasadena, California, in the spring of 1950. After just a year in the minor leagues, Carrasquel was appointed the successor to Hall of Famer Luke Appling, who had been a fixture at Comiskey Park since the early 1930s. At 42 years of age, Appling had played 141 games at short in 1949, hitting .301. However, sportswriter Ed Fitzgerald later echoed a sentiment no doubt held by the White Sox brass at the time. “Appling could still hit the ball hard, but he had slowed up so badly that the White Sox pitchers weren’t getting anything like the protection they deserved. It wasn’t Luke’s fault. It was just a case of time winning another victory.”10

Carrasquel had a prominent role to fill and from Opening Day 1950 he measured up to the task. In his major-league debut that April 18, against Ned Garver of the St. Louis Browns, he walked in his first plate appearance and then singled in his first official at-bat. Number 17 – which he wore nearly throughout his career because there are 17 letters in Alfonso Carrasquel – also handled six chances in the field without fault. The White Sox lost at home, 5-3.

Carrasquel hit his first of 55 major league home runs on May 5, at Fenway Park, against Joe Dobson of the Red Sox. His overall play helped prompt the following mid-season prediction from GM Lane: “The new sparkle given our infield by Chico Carrasquel’s play at shortstop and outfielder Gus Zernial’s potential greatness at bat may enable us to finish this season in the upper division for the first time since 1943.”11 (The White Sox finished sixth in the eight-team league.)

On July 16, 1950, a mid-summer afternoon at Yankee Stadium, Carrasquel was at the center of a distinctive and significant ceremony. It was remarkable in that the honoree was a rookie who had played barely three months in the major leagues – the shower of gifts and praises he received would usually be reserved for elite players nearing the end of their careers. It was significant in that a Latin American player, for the first time, was receiving public esteem from North American baseball.

The tribute, or first “International Day” as Collier’s magazine called it, occurred between games of a Sunday doubleheader that was also broadcast in Spanish throughout Latin America. The politically motivated homage was the idea of Walter Donnelly, then U.S. ambassador to Venezuela. Donnelly sought “to focus attention upon the United States as a land of opportunity for all and to combat untruths about this country with which the Communists were poisoning the minds of young Venezuelans.”12

Carrasquel’s bounty included an automobile, luggage, watch, a television set and radio, plus an array of medals (from baseball and various fraternal orders) – not to mention 16,300 Venezuelan bolivars. That sum was then equal to about US$5,000 – five times his signing bonus. Carrasquel’s sister and mother were among those on hand at the New York event. Alfonso himself had just returned from Caracas a week earlier. He had taken advantage of the All-Star break to visit his wife, Marcela Rodríguez. She had given birth to a new son, Omar, born June 5. The couple had married on February 25, 1948, and welcomed their first child, Edgar, 12 months later.

Less than two weeks after “Carrasquel Day” at Yankee Stadium, Chico’s team was preparing for their sixth series meeting of the season against the New York Yankees. Chicago sportswriter Edgar Munzel previewed the series. “Although the White Sox in general are sinking in the American League race like a lead weight in a millpond,” wrote Munzel, “there was one among them who was definitely on the rise. In fact, he was rising to stardom so rapidly he seemed jet-propelled. The shooting star was none other than Alfonso ‘Chico’ Carrasquel, rookie shortstop.”13 When the story came out, Carrasquel’s 24-game hitting streak had just ended.

Carrasquel finished third behind Walt Dropo and Whitey Ford in the American League Rookie of the Year Award balloting. Dropo was the clear choice, with 34 homers and a league-leading 144 RBIs. Though he pitched only half a season, Ford made a strong impression with his 9-1 record and 2.81 ERA. Carrasquel – with 4 homers, 46 RBIs, a .282 average (his best in the majors), and sparkling play at short – also finished 12th in the voting for AL Most Valuable Player.

“The only thing that keeps general manager Frank Lane from grinning all over the place,” wrote Bob Broeg shortly after the season, “is a recent knee operation necessitated by Chico’s habit – like that of Pepper Martin – of jamming abruptly to a stop after sprinting from the batter’s box to first base.”14 The damaged knee cartilage forced Carrasquel to miss the last week of his rookie season, but he came back the next season without missing a defensive beat.

Early in the 1951 season, John C. Hoffman of Collier’s described Carrasquel in a feature called “Chicago’s Chico – Baseball’s New Mr. Shortstop.” “Physically, Chico suggests the late Tony Lazzeri, famed Yankee second baseman. High cheekbones betray some Indian blood and he smiles through dark-brown eyes adorning an expressionless countenance. There is good humor in his manner, and his temper is even. He walks with the stride of a panther, dresses elegantly off the field.”15

Hoffman also depicted Carrasquel in the field. “Carrasquel plays deep at his position. His strong accurate arm permits him to stand far back. On fast grounders hit to his left or right, when he is caught off balance, he leaps high into the air after snaring the ball and throws to first base with both feet off the ground.”16 The latter part brings Derek Jeter to mind, though Jeter’s range was not comparable. Carrasquel also had to deal with an occupational hazard of shortstops – he received over 100 stitches for spike wounds throughout his playing days.

At least as early as 1951, his spectacular glove work also made Carrasquel one of the first Latin American players in the United States to receive a national endorsement deal. The Nocona Athletic Goods Company, a small Texas-based manufacturer of gloves, used his photo to complement their “major league quality” products. “Chico handles the hot ones with ease using his Nokona 59 glove…made especially for him,” one of the print ads (from 1954) proclaimed.

After winning just 60 games in 1950, the White Sox picked up to 81 in 1951. This included a 14-game winning streak – the first 11 on the road – from May 15 through May 30. The South Side of Chicago was infected with early pennant fever, as an Associated Press story described. “A crowd of more than 1000 rolled cheers through the LaSalle Street Station as Sox stalwarts detrained. Perhaps the loudest salvo of applause was directed at shortstop Chico Carrasquel.”17

In July 1951, Carrasquel enjoyed what he later described as “my greatest thrill in baseball … my first All-Star Game … because I was the first Latin player to play in one.”18 The fans voted him in over reigning AL MVP Phil Rizzuto. Chico’s selection was reinforced this way by Washington Post columnist Shirley Povich: “If you’re asking how Carrasquel got into the All-Star act with a sub-.300 average, that’s easy. There isn’t a shortstop who’s outhitting him, and there isn’t a rival who deserves mention in the same inhalation with Carrasquel as a defensive man.”19 The AL’s shortstop went 1-for-2, his hit (a single) coming against NL starter Robin Roberts.

The White Sox were still in first place at the All-Star break, but they soon fell out of the hunt, despite Carrasquel’s continued fine play. On July 13 at Comiskey, Chico accepted 18 chances without fault in a 19-inning game against Boston. Two days later, he established a new AL shortstop record of 289 chances without an error. The streak (since surpassed by various players) reached 297. Also, on July 15, Carrasquel kept Sam Zoldak of the Philadelphia Athletics from throwing a no-hitter with a third-inning single.

In August, Look magazine ran a five-page feature centered around Carrasquel and how the White Sox pennant chances were tied to him. It described Carrasquel “at shortstop, covering ground like sunlight, inspiring the rest of the team to outdo itself in trying to match him.”20

As the weekly magazine hit the newstands, a third Carrasquel “edition,” Alfonso Carrasquel Jr., made his happy arrival into the clan. Alfonso Sr. and Marcela had six children in total. Rosalia (born in October 1952) and Roberta (born in August 1956) were numbers four and five; the name of number six is not currently available. In a 2003 interview, Chico admitted to fathering other children from relationships he had with women during the 1960s. He stated that he took responsibility for all of them and that the offspring all bear his last name.21

Manager Paul Richards reasserted the shortstop’s importance to his team and how much he wanted Carrasquel to stay in Chicago: “He’s unquestionably the standout player in our lineup,” said Richards. “He’s so brilliant, in fact, that he pulls the whole ball club up with him, because the rest give out that extra effort to try and keep up with him. If Chico ever got homesick and jumped the ball club like Luis Garcia [a player who went home to Caracas after four days in White Sox training camp], I’d hop a plane and go down to Venezuela after him myself. And if he refused to return, I’d keep right on going.”22

Carrasquel had made such an impact in just two years that after the season his name was even bandied about in one-on-one trade talk involving a supposedly slipping Ted Williams. (The Red Sox great had hit “only” .318 that year.) “We stopped talking about Carrasquel almost simultaneously the moment his name was mentioned,” Frank Lane said in November 1951. “We’ll take Williams and pay him his Boston salary, not the $125,000 given out to gullible reporters in Boston. In return, we’ll gladly pay the proper and required price in player, money, marbles and bubble gum. But,” added a pompous-sounding Lane, “no proper price can possibly include our All-Star shortstop, especially in a deal for a 33-year-old outfielder who couldn’t play shortstop with the aid of three arms and a lacrosse racquet.”23

A Chicago-based fan club also sprang up around the White Sox shortstop. Although the Carrasquelites may have sounded like a musical group from the emerging rock ’n’ roll era, they did not do any singing – except for the praises of their idol. An initial fee of $1.00 brought a one-year membership, with an official card, monthly bulletins, an annual journal, and invitations to monthly meetings during the season. There were periodic autograph parties too, also attended by other White Sox players.

The Carrasquelites had their share of female constituents, who called themselves “Carrasquelettes.” The handsome South American’s appearance brought them together as much as – if not more than – his stylish play. White Sox management appreciated Chico’s appeal to his feminine fans, who regularly boosted home ticket sales.

Carrasquel had signed his 1952 contract for a published $20,000, a good amount then for a third-year player and shortstop. But much to the disappointment of his boosters, their hero floundered in 1952. As the season drew to a close, Edgar Munzel was brutally frank in his criticism. “What has happened to Chico Carrasquel? The most brilliant young shortstop in baseball in 1950 has been playing like just another short fielder. Chico was hog fat last spring. He had slowed down afield and wasn’t hitting anywhere near his 1950 or 1951 pace.”24 Listed at six-foot-even and a normal playing weight of 170 pounds, Carrasquel did not have enough height to distribute the excess, something he could afford even less at his position. A broken finger in late June added to the misery of an inadequately played season of 100 games. “It [the injury] eliminated the possibility that he might play himself into condition through the summer heat,” wrote Munzel.25

Willy Miranda – a Cuban shortstop who was also known for fancy fielding, but who never hit much – subbed for Carrasquel. Over the last two months of the 1952 season, the White Sox (who finished in third place) regularly fielded a lineup of four Hispanic position players – something never seen before in major league baseball. In the infield, either Carrasquel or Miranda played alongside first-year third baseman Héctor Rodríguez. In the outfield, Jim Rivera (a New Yorker whose parents were Puerto Rican) played next to left fielder Minnie Miñoso.

In 1953, Chicago finished third again, albeit with an improved win total of 89. Carrasquel had regained his prior form and it plainly showed. After having ballooned to 192 pounds the previous spring, he had arrived at camp at 180. The trimmer shortstop lifted his average to .279 and made only 18 errors in 758 chances. The fans voted Carrasquel onto the All-Star team over Rizzuto again (he was held hitless in two trips).

In 1954, Chicago fielded its strongest team since 1920, winning 94 games. That was still only enough for third place in the AL behind the Cleveland Indians (who won 111) and the Yankees (who won 103). Carrasquel sustained his All-Star level of play, hitting 12 homers (the most he had in any big-league season). Though he hit just .255, he drew 85 walks – contrary to the perception of Latinos as free swingers, Chico had a good eye, as befit the team’s leadoff hitter. Carrasquel played in every one of the White Sox games in 1954. He was second on the team in RBIs (62) and third in runs scored (106). With the glove, he remained a standout.

That year’s All-Star game had an unprecedented international scope. Chicago Daily Tribune writer Arch Ward, who had conceived of the Midsummer Classic in 1933, wrote that the balloting was conducted “with the cooperation of more than 200 newspapers, radio and television stations, representing the United States, Hawaii, Mexico, Puerto Rico, Cuba, Venezuela and Panama. Orestes Minoso, Chico Carrasquel and Bobby Ávila learned they have many amigos in Latin American countries by landing on the starting squad.”26 Having three Hispanics in the starting lineup was a first in All-Star play. Carrasquel, who played the entire game, was 1-for-5.

The 1951 Collier’s article on Carrasquel had called him “Baseball’s New Mr. Shortstop” – so it was ironic that there was friction between him and baseball’s original “Mr. Shortstop,” Marty Marion, in 1955. Paul Richards had left the White Sox with nine games to go in 1954, after signing a three-year deal to manage the Baltimore Orioles. Marion, a coach, completed the season as manager with a one-year pact to return in the same capacity.

In spring training 1955, Marion fined Carrasquel $100 for missing practice. Carrasquel was said to be ill, but reportedly, a check of his room found it unoccupied. Once the season started, Marion criticized Carrasquel’s defensive play, coming out and saying his shortstop was letting fieldable balls turn into hits from lack of effort. Previously, Carrasquel’s harshest critics had inferred that he “let up” when the game was decided or out of hand, that his level of play was too often equal to the competition, that only first division teams brought out his best. Carrasquel always refuted the charges by responding, “I play hard whether we are winning or losing.”27

In spite of the criticisms, Carrasquel made the All-Star team for the fourth time in five years. Though Chico didn’t match his offensive numbers from 1954, he made double figures (11) in home runs again. At Municipal Stadium in Kansas City, on April 23, he enjoyed perhaps the finest day of his career at the plate. He sprayed five singles and scored five times in a 29-6 rout of the Athletics.

Marion decided to give Carrasquel a few days off before the All-Star Game amid worries about his play in the field.28 It might have been an even more embarrassing message if Carrasquel had been selected to the AL All-Star squad as a starter, but even as a substitute, it still could not have felt good. After the mini-break in mid-season, Carrasquel was back in the lineup and homered in each game as Chicago swept a doubleheader from the Washington Senators.

The White Sox had another respectable year in 1955, but in the end, their 91 wins were still good enough only for third place in the AL. A month after the end of the regular season, they traded Carrasquel to Cleveland. The front office thought he had lost a step, and another Venezuelan shortstop was ready to take over: Luis Aparicio. In 2005, the Hall of Famer said, “Chico was my hero and mentor. He took me under his wing, and I’m grateful to him for making me the ballplayer that I turned out to be.”29 Several days later, another countryman, Luis Sojo, added, “When you talk about shortstops in Venezuela, you mean [Carrasquel]. He was a mentor to everyone, Aparicio, Vizquel. All the Venezuelan players wanted to play shortstop because of him.”30

Lane was not involved in the Carrasquel deal, at least not when it took place; he had become GM of the St. Louis Cardinals. However, a Chicago newspaper report from July 1955 offers additional insight:

“Venezuelan sportswriters burn up the long distance wires to the Comiskey Park office of Frank Lane to keep abreast of Chico’s moves. Lane’s latest contact with south of the border journalists came when one excitedly telephoned to check a rumor that Chico was feuding with field boss, Marty Marion.

‘Marion and Chico aren’t having any trouble,’ Frank said.

‘Are you and Chico having any trouble?’ the Venezuelan asked. Lane said no.

‘Well, is Chico having any trouble with anybody?’

‘Yes,’ said Lane. ‘With American League pitchers.’”31

Carrasquel and outfielder Jim Busby brought slugger Larry Doby from Cleveland, a pretty good indication of Carrasquel’s perceived value around the league. Doby was one year removed from leading the American League in home runs and runs batted in. (Busby was known more for his speed and defense.) In a stamp-of-approval quote, Indians general manager Hank Greenberg said, “By acquiring Carrasquel, generally recognized as the American League’s outstanding shortstop, and Busby, a speedster, who is one of the fine fielders of the league, we believe we have improved our club.”32

Though the shortstop regretted leaving Chicago, he welcomed the trade as a needed parting of the ways from Marion, with whom he had sparred. Chico stated that Marion had his own different way of playing shortstop and that Marion tried to change the way he played.33 The manager said publicly, “We couldn’t stir him up anymore and maybe he’ll do better somewhere else.” Marion took a swipe at Chico’s fielding habits, saying that he would waste time by not moving toward the ball on a double play, that sometimes he would squat to field a ball and sometimes not, and that balls which he would have gobbled up the previous year were going through his legs.34

Carrasquel looked forward to his new team and to another major-league first: a Hispanic double-play combination with Mexican second baseman Bobby Ávila. Carrasquel believed he and Ávila would form the “best such pairing in the American League.”35

Carrasquel had two more of his best days at the plate in 1956. On April 26, against Kansas City, he had a career-best seven RBIs (making him the second Hispanic player after Luis Olmo, and the first in the AL, to get as many in a single big-league game). On August 27, he hit two homers off Hal Griggs of the Senators, marking his only multi-homer game in the majors. Overall, though, he hit a disappointing .243-7-48 in 141 games for his new team.

In 1957, the Indians fell into the second division for the first time in 11 seasons under new manager Kerby Farrell, who replaced Al López. That July, Carrasquel got his one thousandth hit – a single against Chicago’s Jack Harshman. He became the second Hispanic after Bobby Ávila to reach that milestone. Chico also got the last two of his four big-league grand slams that season. The second, also against Chicago, came on August 15. Left fielder Minnie Miñoso nearly brought the homer back into Comiskey Park “when he leaped over the left field fence and had the ball momentarily but it dropped out of his glove over the fence.”36

Though he boosted his average to .276 for the season, with eight home runs, Chico’s playing time was curtailed to 125 games. His fielding seemed to have regressed; he committed 24 errors.

The Indians hired Frank Lane away from the Cardinals over the winter in an effort to improve the club and its attendance. Lane brought in Bobby Bragan – Carrasquel’s manager back at Fort Worth in 1949 – as skipper. Through 1957 and 1,099 major league games in the field, Carrasquel had made only one appearance away from shortstop (two innings at third base in 1956). In 1958, however, he began to appear at third with some frequency. Chico became more acquainted with third base than ever before after the Indians traded him to Kansas City on June 12 for Billy Hunter (who had followed Carrasquel at shortstop at Fort Worth). The Athletics had a good-fielding shortstop in Joe DeMaestri; after acquiring Carrasquel, they moved third baseman Héctor López over to second.

Shortly after joining his new team, Carrasquel tore off seven hits as the A’s swept a doubleheader from the Red Sox. The infielder had five hits, including a double, in the opener, and drove in five runs for the day. Overall, though, he managed only a combined .234-4-34 line for his two clubs, a drop from his .276-8-57 marks of 1957.

As the 1958 World Series was being played, the Athletics sent the 32-year-old Carrasquel to the Baltimore Orioles in an even-up deal for Dick Williams. In Baltimore, Carrasquel was reunited with his former manager, Paul Richards, and (briefly) with Bobby Ávila. Carrasquel was the primary shortstop for the so-so 1959 Orioles. (Willy Miranda, Baltimore’s starter much of the time from 1955, played sparingly in his last big-league season.) Hampered by an injury that left him with just 50% vision in his left eye,37 he hit only .223 in 114 games, the lowest average of his career. His last appearance in the majors came at Fenway Park on September 23, 1959.

Carrasquel rejoined the White Sox in January 1960 as a free agent, but Chicago released him in late April before he played a game. He then went to the Los Angeles Dodgers organization, playing 35 games with their Triple-A team in Montreal. That marked the end of Carrasquel’s career in the U.S., but he remained active in Venezuelan winter ball until 1967. In 816 regular-season games in his homeland, he hit .278 with 46 homers and 357 RBIs. He was a member of four champion teams in the LVBP with Caracas (1947-48, 1948-49, 1951-52, and 1956-57) plus another as a playoff reinforcement with Valencia (1957-58).

While still a star player in Venezuela, Carrasquel managed his Caracas Leones squad to a third-place finish in the 1957-58 winter season. Chico ended up managing in all or parts of 10 winter-league campaigns in his home country. In 1982, again as the manager of the Leones, the 56-year-old Carrasquel became the first Venezuelan to lead his national team to a Caribbean Series title. The Lions captured the bragging rights to Latin American winter ball in Hermosillo, Mexico, winning 5 and losing 1. Carrasquel is one of 11 players to have his uniform number (17) retired by the Caracas club.38

For several years after retiring as an active player, Carrasquel was a scout for the Kansas City Royals and New York Mets. Starting in 1980, he also served as a broadcaster covering the Venezuelan winter league. Carrasquel became a Chicago White Sox Spanish-language radio color man from 1990 to 1996, stepping down at the age of 70. As an extended part of his radio duties, Chico represented the White Sox community relations department. The position offered the outgoing former player an opportunity to interact frequently with a new generation of Chicago fans.

In 1991, the LVBP honored Carrasquel by naming its reconstructed Puerto la Cruz Stadium after the country’s first big league all-star. The stadium, home to the Anzoátegui Caribes, hosted the 1994 and 1998 Caribbean Series.

In 2003, the former shortstop was among the inaugural class of players enshrined in his country’s Baseball Hall of Fame in Valencia. That January, in Caracas, Chico suffered an armed carjacking at the hands of two thugs. Luckily no one was seriously injured, including his sister, who was with him at the time.

Carrasquel, throughout his later years, stayed close to the game. His fame helped him as a tireless promoter of youth baseball in Venezuela. In 2004, he established a non-profit organization in his name to help broaden the horizons of underprivileged children in his nation. His sister, Emilia Carrasquel, remained one of the foundation’s Venezuelan board members as of 2014.

One of the last public appearances for Carrasquel occurred on April 13, 2004, at U.S. Cellular Field. Confined to a wheelchair, he joined three other great Venezuelan shortstops – Hall of Famer Luis Aparicio, Dave Concepción, and Ozzie Guillén (then the White Sox manager) – in throwing out ceremonial first pitches before Chicago’s home opener against the Kansas City Royals.

The fondly-remembered player, who had been suffering from diabetes, died of a heart attack on May 26, 2005, in Caracas. He was 79. He was predeceased by his first wife, Marcela, and second spouse, Conny (both women died several months apart in 2000). During a nationally televised speech, Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez declared two days of mourning for the idol. “¡Viva Carrasquel!” he shouted. Ozzie Guillén said, “I don’t think he was the greatest player ever to come from the country. But to me, he was the greatest man to come from Venezuela.”39

Sources

Internet resources

baseball-reference.com

retrosheet.org

ChicoCarrasquel.org

purapelota.com (Venezuelan statistics)

Books

Rich Westcott, Splendor on the Diamond, Gainesville, Florida: University Press of Florida, 2000.

Notes

1 Ray Gillespie, “Veeck, in Deepest Plunge, Comes Up With a Shortstop.” The Sporting News, October 22, 1952, 13.

2 Marcos Bretón and José Luis Villegas. Away Games: The Life and Times of a Latin American Player, New York, New York: Simon & Schuster, 1999: 121.

3 Tim Wendel, The New Face of Baseball: The One-Hundred-Year Rise and Triumph of Latinos in Baseball, New York, New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2004: 75.

4 Harold C. Burr, “3 Rookies Brighten Brooks.” The Brooklyn Eagle, January 6, 1949, B1.

5 Dave Nightingale, “Lost in America,” The Sporting News, August 3, 1992, 11-15.

6 John Cronley, “Texas to Send Bumper Crop to Main Tent,” The Sporting News, September 21, 1949, 13.

7 The trade stipulated that if the minor-leaguers – pitcher Chuck Eisenmann and infielder Fred Hancock – did not show enough promise to suit Rickey, Lane would take either player back and add another $10,000 to the transaction. Hancock did not live up to his billing, in Rickey’s eyes, and was returned for the additional subsidy.

8 John P. Carmichael, “Sox Shaking Leg for Lane,” The Sporting News, December 14, 1949, 10.

9 Bob Broeg, “Strong Rookie All-Stars Show .283 Mark,” The Sporting News, November 1, 1950, 5.

10 Ed Fitzgerald, “How the White Sox Are Building a Winner,” Sport. April 1954.

11 Jack Cuddy, “Quick-quality Farming Policy Is Paying Rapid Dividends for Chisox,” United Press, July 17, 1950.

12 John C. Hoffman, “Chicago’s Chico Baseball’s New ‘Mr. Shortstop’ ” Collier’s, April 28, 1951, 24-28.

13 Edgar Munzel, “Carrasquel Zooms to Stardom as White Sox Continue to Sink,” The Sporting News, August 9, 1950, 14.

14 Broeg, “Strong Rookie All-Stars Show .283 Mark”

15 Hoffman, “Chicago’s Chico Baseball’s New ‘Mr. Shortstop’”

16 Hoffman, “Chicago’s Chico Baseball’s New ‘Mr. Shortstop’”

17 “11-game Streak Has Fans Joyous.” The Washington Post, May 29, 1951, 14. Richards’ squad won 15 straight road games, two short of the AL record of 17, set by Washington in 1912.

18 Rich Marazzi, and Len Fiorito, Baseball Players of the 1950s, Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2004: 58.

19 Shirley Povich, “This Morning,” The Washington Post, July 2, 1951, 12

20 Tim Cochrane, “The Great Chicago Fire…” Look, August 5, 1951, 40 (five non-concurrent pages).

21 Milagros Socorro, “Alfonso Carrasquel,” Analitica.com, September 12, 2003.

22 Edgar Munzel, “Chico Gives Pale Hose Chic Trick at Short,” The Sporting News, May 16, 1951, 3.

23 Ed Burns, “Lane Bars Ted-Chico Deal,” The Sporting News, November 21, 1951, 7.

24 Edgar Munzel, “Senor Chico Due For Plain English Winter Warning,” The Sporting News, September 24, 1952, 8.

25 Munzel, “Senor Chico Due For Plain English Winter Warning”

26 Arch Ward, “4,272,470 Fans Pick All-Star Lineups.” The Chicago Daily Tribune, July 5, 1954.

27 Jack Orr, “Are Chico’s Troubles Behind Him?” Sport, June, 1954, 34-37.

28 Edgar Munzel, “Old Master Marty Critical of Chico’s Work at Shortstop,” The Sporting News, July 20, 1955, 16.

29 “Former White Sox shortstop Chico Carrasquel passes away,” MLB.com, May 26, 2005.

30 Anthony McCarron, “Sojo Fondly Remembers Carrasquel,” New York Daily News, May 31, 2005.

31 David Condon, “In The Wake of the News.” Chicago Daily Tribune, July 22, 1955.

32 Hal Lebovitz, “‘We Needed Bat Threat at Short’–Senor,” The Sporting News, November 2, 1955, 3.

33 “Chico Likes Lopez Better,” United Press, March 19, 1956.

34 Hal Lebovitz, “Rivals Won’t See Wooden Indians on Paths–Senor,” The Sporting news, December 7, 1955, 21.

35 Gordon (Red) Marston, “Nothing Could Surprise Me Since Lane Left Chicago – Chico,” The Sporting News, November 2, 1955, 4.

36 “Carrasquel Drives Grand Slam as Indians Beat White Sox, 5-4,” New York Times, August 16, 1957.

37 “Chico Carrasquel Has a Serious Eye Injury,” Associated Press, September 17, 1959.

38 The other ten: Pompeyo Davalillo, César Tovar, Vic Davalillo, Antonio “Tony” Armas, Baudilio “Bo” Díaz, Urbano Lugo, Gonzalo Márquez , Omar Vizquel, and Andrés Galarraga. José Luis Guaymare, “El Caballero del Béisbol,” personal blog, (http://guayma.blogspot.com/2009/12/el-caballero-del-beisbol.html)

39 Bob Vanderberg, “‘Chico’ Carrasquel, first Latin player in All-Star Game, dies at 77 [sic],” Chicago Tribune, May 26, 2005.

Full Name

Alfonso Carrasquel Colon

Born

January 23, 1926 at Caracas, Distrito Federal (Venezuela)

Died

May 26, 2005 at Caracas, Distrito Federal (Venezuela)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.