April 19, 1897: Beaneaters’ furious comeback falls short against Phillies

At the start of the 1897 season, the Boston Beaneaters set out to regain the National League crown. Winners of three league titles earlier in the decade, the Beaneaters suffered through injuries, aging of key performers, and a ballpark fire in 1894 as the Baltimore Orioles built a new championship team. The Orioles, managed by Ned Hanlon, surpassed the Beaneaters and won three titles of their own from 1894 to 1896. Boston manager Frank Selee, who in 1896 led the club to a fourth-place finish, was determined to build another champion.

At the start of the 1897 season, the Boston Beaneaters set out to regain the National League crown. Winners of three league titles earlier in the decade, the Beaneaters suffered through injuries, aging of key performers, and a ballpark fire in 1894 as the Baltimore Orioles built a new championship team. The Orioles, managed by Ned Hanlon, surpassed the Beaneaters and won three titles of their own from 1894 to 1896. Boston manager Frank Selee, who in 1896 led the club to a fourth-place finish, was determined to build another champion.

Right-hander Kid Nichols, a perennial 30-game winner, anchored the pitching staff, but the rest of the rotation needed help. Jack Stivetts won 22 games in 1896, but suffered from chronic arm pain and was no longer able to take the mound in a regular turn. Stivetts was a fine hitter, though, and found more playing time in the outfield. Jim Sullivan, 11-12 in 1896, was mediocre, so Selee promoted two youngsters, right-hander Ted Lewis and lefty Fred Klobedanz, to regular roles. Lewis and Klobedanz had limited experience, but the Boston manager saw both as future stars.

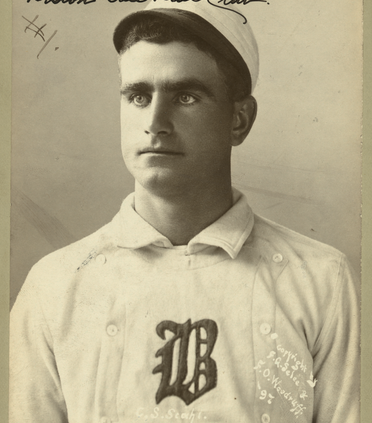

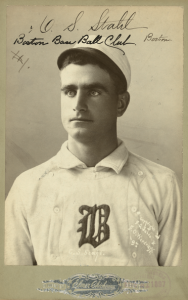

In the outfield, captain Hugh Duffy remained from the championship days, and speedy Billy Hamilton was the top leadoff man in the game. Right field, however, was a problem area, as Jimmy Bannon fell off so sharply that Selee released him and gave his roster spot to a rookie named Charles “Chick” Stahl. Stahl began the campaign on the bench. Second baseman Bobby Lowe and shortstop Herman Long gave the Beaneaters a solid keystone combo, while third baseman Jimmy Collins was headed for stardom in his third season. Veteran Charlie Ganzel and second-year player Marty Bergen took care of the catching.

Perhaps the key addition to the Boston lineup was Fred Tenney, who had joined the club in 1894 as a catcher but spent most of the 1896 campaign in the outfield. Selee was dissatisfied with veteran first baseman Tommy Tucker, a behavioral problem who had often clashed with his manager. Tucker’s best days were behind him, so the manager toyed with the idea of moving Tenney to first. Though Tenney was only 5-feet-9-inches tall, this was the position the Brown University product was born to play. “Tenney’s way is far different from that of other first basemen,” wrote a Chicago News reporter in 1897. “He reaches his hands far out for the ball, and stretches his legs, so that he is farther out from the bag on every throw than any other first baseman in the league.”1 On Opening Day, however, Tucker manned the first sack while Tenney played right field.

The Boston club had won six National League titles in their history, but their opponents, the Philadelphia Phillies, had captured none since joining the league in 1883. Still, the Phillies harbored championship aspirations of their own. They possessed the most powerful offense in the game, led by hard-hitting outfielders Sam Thompson and Ed Delahanty. The Phillies also counted on a big season from the best young player on the club, a rookie first baseman named Napoleon Lajoie. A strongly built 22-year-old from Rhode Island, Lajoie had impressed the Philadelphia fans in a 39-game trial in 1896.

The Phillies, a hard-drinking team known for their curfew-breaking exploits, began the season with a strict disciplinarian at the helm. Philadelphia management hired a 29-year-old former outfielder, George Stallings, to keep the players on the straight and narrow. Stallings was a sharp-tongued perfectionist, often sarcastic and cutting in criticizing his men. The Sporting News called him “the gentleman whose mouth is always in a state of volcanic eruption,”2 and it remained to be seen how the Phillies would respond to his leadership. Stallings was also keen to improve a pitching staff that had allowed more than five earned runs per game in 1896. Pitching was a perennial problem for the Phillies, and the team had finished in eighth place in 1896 despite scoring more runs than every other club except the Orioles.

On Monday, April 19, 1897,3 a state holiday celebrated in Massachusetts as Patriots Day, more than 14,000 Bostonians squeezed inside the South End Grounds. The club erected rope barriers in the outfield and along the sidelines to house the overflow. Outside, another several hundred fans milled around, unable to gain entry. On this day, the Beaneaters and Phillies had the attention of the baseball world all to themselves, as the rest of the teams did not begin their schedules until Thursday of that week. It was, according to an optimistic headline in Sporting Life, “The Brilliant Opening a Happy Augury of a Successful Season Artistically and Financially.”4 The crowd settled down to watch the duel between Boston’s Kid Nichols and Philadelphia right-hander Al Orth.

While Orth breezed through the Boston lineup, allowing no hits in the first four innings, Philadelphia scored in the fifth. Sam Gillen led off with a single and Billy Nash, after a failed sacrifice attempt, singled down the first-base line as Gillen reached third. Orth, a good-hitting pitcher, then drove in the first run of the 1897 season with a bloop hit. Two groundouts scored Nash, and the Phillies led, 2-0.

Boston finally hit safely off Orth in the bottom of the fifth, when Lowe singled with two outs but was stranded on first. Hamilton singled and stole second in the sixth but advanced no farther. By the time Lajoie scored the third Philadelphia run in the eighth, Orth had allowed only three Boston hits.

The Phillies tacked on three more runs in the ninth. With Orth and Bill Hallman aboard with singles, Lajoie belted his third hit of the day, a line drive over the left-field fence for a three-run homer, the first in the National League in 1897. This blow put the Phillies ahead 6-0, and the game appeared to be over.

However, Orth faltered in the bottom of the ninth, and the Beaneaters nearly pulled out a victory. Manager Selee sent Chick Stahl, his rookie outfielder, to bat for Nichols. Stahl, in his major-league debut, worked Orth for a walk. Orth retired Billy Hamilton, but Fred Tenney drilled a single to right. Stahl raced for third as Sam Thompson’s throw from the outfield had him beaten easily, but third baseman Nash dropped the ball as Stahl slid into third safely.

Herman Long, who committed three errors that day (his “fingers were all thumbs,” according to Sporting Life5), then flied out to Delahanty in left, scoring Stahl. Duffy singled to score Tenney. Collins and Lowe followed with singles, loading the bases with two out. This brought Tommy Tucker to the plate, and the veteran first sacker drove a liner to right that nearly tied the game. The ball hit the top of the fence, inches from going over, and Tucker made it to second for a double while all three runners crossed the plate. The score was now 6-5, with the potential tying run on second.

Charlie Ganzel, the ninth batter of the inning, could have tied the score with a safe hit, but he batted a weak grounder to Gillen, who threw to Lajoie at first to end the game. The Phillies had escaped with a win in George Stallings’ managerial debut. “The visitors,” said the Boston correspondent to The Sporting News, “played the better ball and deserved to win.”6

After the loss on Patriots Day, the Beaneaters went on the road and won only one of their next seven games (with one tie), dropping to last place by the end of April. Still, Chick Stahl, who may have impressed Selee with his daring baserunning in the opener, found more playing time and emerged as one of the game’s brightest rookie stars. Before long Selee placed Stahl in right field, moved Fred Tenney to first base, and shifted Tommy Tucker to the bench. So successful was this arrangement that Tucker appeared in only three more games before Selee sold him to Washington in early June. Tenney and Stahl sparked Boston’s climb up the standings, and a 17-game winning streak in June boosted the Beaneaters into first place. They held the lead until mid-September, lost it briefly to the surging Orioles, then rallied to win the pennant.

The Phillies, in the meantime, were unable to build on their Opening Day victory. Napoleon Lajoie emerged as a major star in his first full season, batting .361 and leading the league in slugging percentage, but the players quickly grew tired of their sarcastic new manager. Torn by dissention and their annual pitching woes, they finished the 1897 season in 10th place. Stallings was fired after a poor start in 1898, and not until 1915 would the Phillies finally win their first National League title.

Notes

1 Mark Sternman, “Fred Tenney,” sabr.org/bioproj/person/40c98ad2.

2 The Sporting News, July 3, 1897: 5.

3 This was also the date of the first Boston Marathon, which was run a few hours earlier.

4 Sporting Life, April 24, 1897: 2.

5 Ibid.

6 The Sporting News, April 24, 1897: 2.

Additional Stats

Philadelphia Phillies 6

Boston Beaneaters 5

South End Grounds

Boston, MA

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.