April 6, 1973: Something’s missing: No Clemente in right field for Pirates

“You kept looking in right field, and he wasn’t there,” said Pittsburgh Pirates manager Bill Virdon on Opening Day in 1973. “I kept looking out there.”1

“You kept looking in right field, and he wasn’t there,” said Pittsburgh Pirates manager Bill Virdon on Opening Day in 1973. “I kept looking out there.”1

It was the dawn of a new era for the Pirates. Immensely popular Roberto Clemente had died about three months earlier, on New Year’s Eve, when his plane crashed off the coast of San Juan on his home island of Puerto Rico. The 18-year veteran, who had collected his 3,000th hit in his last official at-bat of the 1972 season, had been involved in a humanitarian mission to Nicaragua to assist victims of a massive earthquake.

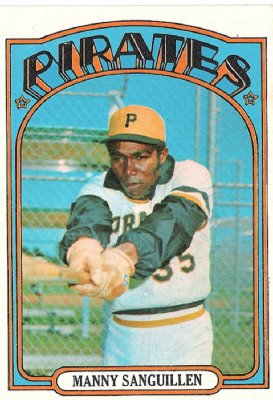

The Pirates clubhouse was subdued on April 6 as players prepared to take on their divisional rival St. Louis Cardinals to kick off the season. Lacking was the typical raucous party atmosphere as reminders of Clemente’s absence were everywhere. The “Great One’s” two lockers stood empty. Affable Manny Sanguillen, a two-time All-Star catcher, had the unenviable task of replacing Clemente in right field. “Last night I dreamed about him,” said Sanguillen about his close friend, whom he had seen the day he died. “I thought about when we were in the ocean hunting for him. I don’t want to talk too much about it.”2 GM Joe L. Brown, fully aware of the pressure-laden task, offered words of reassurance. “Sanguillen is a good ballplayer, he’ll handle the job well,” he declared.3 Other Pirates echoed Sangy’s comments; their reluctance to talk about Clemente was not a desire to forget the player; rather, they were eager to erase the bitter memories of their decisive Game Five walk-off loss to the Cincnnati Reds in the NLCS and begin their quest for a fourth straight NL East title.

Spring training had produced a few surprises for the Bucs lineup. Sanguillen’s move paved the way for highly touted prospect Milt May behind the plate; slugger Willie Stargell with his creaky knees was shifted to left field to make room at first base for Bob Robertson,who had apparently recaptured in spring training the power stroke that had produced 53 home runs in 1970-1971. Rennie Stennett, a flashy 22-year-old Panamanian, started at second instead of Dave Cash, who had taken over taken the same positionfrom another legend, Bill Mazeroski two years earlier.

The pitching matchup featured two of the league’s marquee right-handers. Toeing the rubber for the Pirates was 31-year-old Steve Blass. Coming off his best season (19-8, 2.49 ERA), Blass had a 100-67 slate and was making his third Opening Day start. Skipper Red Schoendienst’s Cardinals were coming off their second losing season (75-81) in three years, but as usual, Bob Gibson was on the mound – inaugurating a season for the ninth straight time. The 37-year-old was coming off a strong season (19-11, 2.46 ERA), which had pushed his career record to 225-141.

Three Rivers Stadium, was packed with 51,695 spectators for the Friday afternoon game. It was the then-largest crowd in the history of the round, all-purpose stadium, home to both the Pirates and NFL Steelers. No doubt many were on hand for the somber and tear-jerking pregame ceremony honoring Clemente. In attendance were the player’s wife, Vera; their three children, Roberto Jr., Luis, and Enrique; and his mother, Luisa Walker Clemente. Situated near home plate, NL President Warren Giles presented Mrs. Clemente with her husband’s 12th Gold Glove Award and a lifetime golden pass to attend NL games. The Pirates also announced formally that they were retiring Clemente’s number 21. Hanging from the right-field wall, just above where Clemente had patrolled, was another visual reminder of his absence, a homemade banner, “Thank you, Roberto… We’ll never forget the Great One.”4

Blass labored from the outset. After walking two in the first, he unraveled in the second, issuing another free pass and yielding three singles and a double, and heaving a wild pitch. The Cardinals scored three runs, but it could have been worse. Blass threw out Ken Reitz trying to stretch his single and picked off Lou Brock at first. It was a tough start to the season for the then six-time stolen base champ Brock, who had been thrown out trying to steal an inning earlier. No one could have surmised that Blass’s performance was the beginning of his sudden and psychologically distressing exodus from the big leagues. His loss of control seemingly overnight led to what pundits began calling “Steve Blass Disease,” an unwelcomed moniker still used four decades later. In the third, Blass loaded the bases with a single, walk, and hit batter. Groundouts by Ted Simmons and Reitz brought home two more runs and the Cardinals led, 5-0.

Blass’s struggles contrasted sharply with Gibson’s early dominance. He yielded his first hit, a triple by Al Oliver, with two outs in the fourth.

Through five innings the Cardinals maintained their 5-0 lead. After southpaw swingman Luke Walker, in relief of Blass, tossed his first of two scoreless frames, the Pirates finally got on board in the sixth when Stennett drew a leadoff walk, scampered to third on a passed ball and Sanguillen’s single, and then scored on Oliver’s sacrifice fly. The Bucs tacked on another run in the seventh on Richie Hebner’s solo shot, which bounced off the top of the right-field wall. Ironically, Hebner had been given, but missed, the “take” sign from third-base coach Mazeroski.

The Pirates had an explosive offense, even without Clemente. In 1972 the team had led the majors in batting average (.274) and slugging (.397), and finished third in runs scored (691), just 17 fewer than the league-leader Houston Astros. A five-run deficit didn’t concern Blass, in the Pirates clubhouse. “A pitcher can get behind on this team,” he said. “[Y]ou never know when this team is going to get a ton of runs.”5

After an offseason acquisition, left-hander Jim Rooker, held the Redbirds scoreless in the eighth, the Pirates erupted in the bottom of the frame. Consecutive one-out singles by Sanguillen and Oliver and a walk to Stargell sent Gibson to the showers. He was replaced by Diego Segui, a crafty right-hander from Cuba who had led the AL with a 2.56 ERA as a swingman for the Oakland A’s in 1970. Segui fanned Robertson, then Hebner knocked in two runs with a bloop to pull the Bucs to within one run. “I was lucky,” said Hebner, whom sportswriters affectionately called “The Gravedigger” because of his offseason job. “It was a good pitch. I broke my bat.”6Pinch-hitting for Rooker, Gene Clines smashed a hard liner into the left-center-field gap. With his dazzling speed, Brock ran down the ball, but it hit off the tip of his glove and rolled away (no error was charged). Clines raced to third, while Stargell and Hebner scored, giving the Pirates a 6-5 lead. Clines, whom most sportswriters expected to be the everyday left fielder and was coming off a superb campaign, batting.334, was upset about his role as a bench player and expressed his desire to be traded. After May was walked intentionally to place Pirates on the corners, Cash, who had pinch-hit for Walker the previous inning and took over at the keystone bag, hit a grounder which shortstop Ray Bussemisplayed for his second error of the game, enabling Clines to score.

Pirates left-handed reliever Ramon Hernandez worked around a leadoff walk in the ninth, retiring the next three hitters on outfield flies to preserve the Pirates’ come-from-behind victory in 2 hours and 2 minutes.

Rooker earned his first NL victory, after 21 wins (and 44 losses) for the Kansas City Royals, and Hernandez picked up the save. The loss went to Segui. The Pirates were led by Hebner, who collected three of the team’s eight hits, scored twice, and knocked in three runs. Stargell, who had assumed Clemente’s mantle as clubhouse and team leader, recognized the importance of the game. “Man, it’s a big win,” he said. “It means a lot to a team winning this way, coming from behind like we did. It means a lot more when we do it against a pitcher like Gibson.”7

The game underscored the Pirates’ resiliency on an emotionally charged afternoon. The trauma of Clemente’s tragic death at the age of 38 was still on everyone’s mind whether the players talked about it or not. “I don’t really want to be there (in right field),” said Sanguillen after the game, “but I have to go on because God, you know, take the Great One away from us. So I have to do my best because that’s the only way.”8

It was difficult for the Pirates to acclimate to life without Clemente in 1973. The Sanguillen experiment in right field failed miserably and he was moved back to catcher beginning June 15. In early July, Richie Zisk, in his first full season, took over right field. The Pirates finished with their first losing season (80-82) since 1968.

This article appears in “Moments of Joy and Heartbreak: 66 Significant Episodes in the History of the Pittsburgh Pirates” (SABR, 2018), edited by Jorge Iber and Bill Nowlin. To read more stories from this book at the SABR Games Project, click here.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also accessed Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, SABR.org, and The Sporting News archive via Paper of Record.

Notes

1Phil Musick, “Now Playing Right Field …,” Pittsburgh Press, April 7, 1973: 6.

2Ibid.

3Charley Feeney, “Robby, 1B, Stargell, LF, Take Up Slack,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, April 6, 1973: 10.

4Musick.

5Bob Smizik, “Pirates Teach Rooker a Lesson in Winning,” Pittsburgh Press, April 7, 1973: 7.

6Ibid.

7Pat Livingston, “Well, Maybe the First Is the Toughest,” Pittsburgh Press, April 8, 1973: D3.

8Ibid.

Additional Stats

Pittsburgh Pirates 7

St. Louis Cardinals 5

Three Rivers Stadium

Pittsburgh, PA

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.