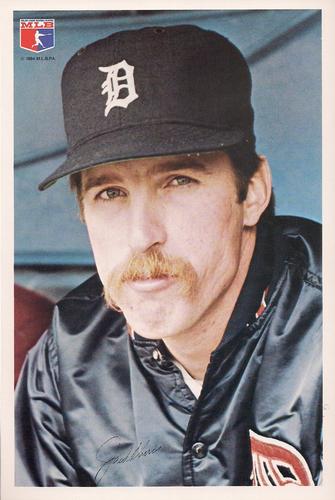

April 7, 1984: Jack Morris throws a no-hitter against the White Sox

No-hitters are often remembered for the dramatic defensive plays that preserved them. The later it comes in the game, the more dramatic the play is; sometimes it’s even the 27th out.1 Other times it’s the very first out, when no one could imagine what is at stake.

No-hitters are often remembered for the dramatic defensive plays that preserved them. The later it comes in the game, the more dramatic the play is; sometimes it’s even the 27th out.1 Other times it’s the very first out, when no one could imagine what is at stake.

Rudy Law of the Chicago White Sox led off the bottom of the first inning against the Detroit Tigers on April 7, 1984, and launched a blast to right field. The home crowd cheered, thinking extra bases or maybe a round-tripper. But Kirk Gibson raced back and made the catch at the wall. Gibson had been stymied by swirling winds the day before on a deep double that scored a run, but today he made the play. “When … the ball [left] the bat I didn’t think Gibson was going to catch up with it,” said commentator Lorn Brown on the White Sox radio broadcast. “He played it perfectly.”2 That was the first out. Jack Morris then struck out Carlton Fisk and Harold Baines to end the frame.

It was a chilly Saturday afternoon at Comiskey Park. The season was less than a week old. The game marked the season debut of NBC’s Game of the Week, with Vin Scully and Joe Garagiola starting their second year together in the booth. NBC chose the game in order to feature the American League debut of new White Sox pitcher Tom Seaver, but a rainout earlier in the week bumped back Seaver’s start and spoiled that storyline.3 It was too early to draw any conclusions, but the Tigers were 3-0 after beating Tony La Russa’s defending AL West champion White Sox 3-2 the day before and looking to finish out a perfect first week.

In the top of the second, Lance Parrish drew a leadoff walk off White Sox starter Floyd Bannister, and Chet Lemon– who played for the White Sox for seven seasons before being traded to Detroit – homered to give the Tigers a 2-0 lead.

Morris retired the White Sox in order his first time through the lineup. But in the bottom of the fourth, Morris seemed to go from dominant to derailed. Law led off and worked the count to 2-and-0. Then Morris licked his hand and home-plate umpire Durwood Merrill charged Morris with a ball for going to his mouth on the mound. An angry Morris walked toward the plate and waved his arms, but the count was 3-and-0. Morris walked Law, then walked Fisk, and a;so walked Baines. The bases were loaded with nobody out. It was still too early to think about a no-hitter; Morris was just looking for a way out of the inning.

But the next batter, Greg Luzinski, checked his swing and bounced back to the mound. Morris fired to Parrish for the force out at home, and Parrish relayed to first to retire Luzinski. Suddenly there were two outs and still no runs across. Morris later called it “the turning point of the game.”4 Then Morris struck out Ron Kittle to end the inning and leave the White Sox not only without a run, but still without a hit.

Lemon led off the fifth inning with a double, and Gibson followed with another double to bring him home. After moving to third on a sacrifice bunt by Tom Brookens, Gibson headed home on a grounder to second by Lou Whitaker. Julio Cruz threw to home plate, but Gibson beat the tag. The Tigers led 4-0.

Morris gave up a walk but nothing else in the fifth. That’s when he, the crowd, and a national TV audience started thinking seriously about a no-hitter. “I knew I had it going in the fifth inning,” he said. “Usually by the fifth inning I don’t have a no-hitter going. I looked up at the board and saw zero.”5

Morris would need more defensive help to keep it that way. Dave Bergman came in as a defensive replacement at first base in the seventh inning and immediately made his mark.

“That’s got to be tough, in the cold, coming off the bench to play defense in a no-hitter,” Scully said on NBC.6 As soon as Scully said it, Tom Paciorek hit a hard line shot toward first. Bergman reached and made the backhand stab.7

After the seventh inning, everyone in the Tigers dugout seemed tense except Morris. A couple of hecklers next to the dugout were loudly reminding Morris what was at stake – the only ones in the vicinity who dared to bring it up. But Morris turned to the hecklers and stated, “I know I’ve got a no-hitter, and you just sit back and watch the next two innings because I’m going to get it.” Tigers pitching coach Roger Craig, who was in the Brooklyn Dodgers dugout for Don Larsen’s perfect game in the 1956 World Series, said, “That shocked the superstitious types in our dugout, but also broke the tension.”8

“I’m not superstitious,” said Morris, whose only career one-hitter so far, in 1980, featured a first-inning single and thus no suspense. “I told Roger, ‘Hey, I’ve come this far, I’ve got to do it.’ Sure, I’m cocky, but I have to be.”9

Morris was known for his ego and his volatile temperament, which could alienate umpires, the media, and even teammates at times. Sometimes it seemed to be his undoing, as it was when he walked the bases loaded in the fourth after being penalized. And yet his fiery drive could also push him to beat the odds, as he did in escaping that inning unscathed. Now it may have given him an edge as the tension mounted.

But if Morris was staying loose, the rest of the Tigers were nursing nerves. They remembered what happened at Comiskey Park not quite one year earlier. On April 15, 1983, Detroit’s Milt Wilcox took a perfect game into the ninth inning and had two outs. Then pinch-hitter Jerry Hairston came up for Chicago and singled to center. Wilcox got the next batter to ground out to finish one hit short of perfection.

“Because of what Milt went through, I wanted this one double for Morris,” said Tigers shortstop Alan Trammell.10

Improbably, in the eighth inning – in the same park and nearly the same date and situation – Jerry Hairston came in to pinch-hit for the White Sox. Sure enough, he hit a hard groundball down the first-base line. But Bergman shone again. He slid to his knees and snared the ball, and threw to Morris at first for the out. After two more groundouts, Morris was three outs away.

Morris started the bottom of the ninth by getting Fisk to pop out to Bergman at first. “I wanted to get the first hitter out. I threw Fisk a good forkball and got him,” he said. “Then I got gung-ho about the no-hitter.”11

Next up was Baines. Morris considered him the toughest out in the White Sox lineup.12 But Baines bounced back to the mound, and Morris was one out away.

Luzinski, the cleanup hitter, stepped in. “How about the loneliness of a man on a mound one out away from a no-hitter?” said Scully.13 With the count 2-and-2, one strike away, pouring everything he had into the pitch, Morris fell off the mound in his delivery and bounced the ball to the plate. Then, with a full count, Morris fired a beauty that just missed the outside corner. Parrish rose out of his crouch to celebrate but stalled when he didn’t hear the call. The Comiskey crowd, on its feet and hoping to see history, booed Merrill, the umpire.

Morris slapped his hip in disbelief but kept his cool. He saw Dave Stegman come into the game to run for Luzinski. Stegman played for the Tigers when Morris broke into the big leagues and roomed with him on the road. “Relax, roomie,” Morris called over to Stegman. “You’re not going anywhere.”14

Kittle was up next. He had struck out to end that nearly calamitous fourth inning. Morris got ahead of him in the count, 1-and-2, and then unfurled his signature pitch, the forkball. Kittle waved at the pitch as it tailed away for strike three.

The crowd cheered, the dugout emptied. Parrish rushed toward the mound, and he and Morris collided in an embrace.

“I’m so excited I can hardly talk,” Morris said afterward. “I’ve had better stuff before, but anytime you throw a no-hitter or even a shutout, you have to have luck.”15

“It wasn’t a Picasso, but it might have been a Rockwell,” said Merrill.16

Few fans had been watching as nervously as Carol Morris, in Birmingham, Michigan. She had two televisions and a radio all tuned to the game, but couldn’t bear to idle near any of them as her husband collected hitless innings. “I was so nervous, I cleaned my whole house,” she said.17 After waxing the kitchen floor, she finally settled in front of the TV to watch the last three innings. “It seemed like an eternity. I got more nervous with each inning, each out, each pitch.”

Morris became the fourth Tiger to throw a no-hitter, the first since Jim Bunning in 1958.18 He also tied the mark for the earliest date of a no-hitter. Ken Forsch threw one for the Astros on the same date in 1979.19 (Bob Feller pitched a no-hitter on Opening Day in 1940, but that happened on April 16.)

Detroit News columnist Joe Falls said the no-hitter showed how much Morris had grown.

“Something always seemed to be going wrong with this scowling right-hander,” Falls wrote. “He seemed to be fuming all the time. … Now, at the age of 28, the man has matured. … More than mastering the best team in the American League West, he has learned to master himself.”20

The timing was right for the Tigers, who improved to 4-0 and would quickly take control of the AL East. Morris’s no-hitter provided a hint that a historic April might be in store for the 1984 Tigers — as well as a memorable October.

Sources

In addition to the sources mentioned in the Notes, the author obtained pitch count information from an NBC recording of the game on Youtube (since removed from access) as well as consulting Baseball-reference.com and Retrosheet.org:

http://www.baseball-reference.com/boxes/CHA/CHA198404070.shtml

http://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1984/B04070CHA1984.htm

Notes

1 A recent example is Steven Souza Jr.’s diving catch to complete Jordan Zimmermann’s no-hitter on the final day of the 2014 season.

2 Detroit Tigers at Chicago White Sox. WMAQ, Chicago, April 7, 1984. Accessed at youtube.com/watch?v=UBu9a0Jyi4I.

3 “Garagiola, Scully Take ‘Giant Egos’ Into 2d Year,” Detroit Free Press, April 7, 1984: 32.

4 Joe Mooshil, “Morris No-hits the White Sox,” Spokane (Washington) Spokesman-Review, April 8, 1984: 45.

5 Ibid.

6 Jerry Green, “Scully, TV Cameras Capture Drama Perfectly, Detroit News, April 8, 1984: 1C.

7 Roger Craig noted that Bergman was playing off the bag with a runner on first only because the slow-footed Luzinski (who had walked) wasn’t a threat to steal. “Sparky admitted later that he would have had Bergman holding almost any other runner on first, which would have allowed Paciorek’s line drive to reach right field for a base hit.” See Roger Craig and Vern Plagenhoef, Inside Pitch: Roger Craig’s ’84 Tiger Journal (Grand Rapids, Michigan:Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1984), 15.

8 Craig, 16.

9 Bill McGraw, “The Right Stuff,” Detroit Free Press, April 8, 1984: 33.

10 Tom Gage, “Morris’ Masterpiece Silences White Sox,” The Sporting News, April 16, 1984: 25.

11 Mooshil, “Morris No-hits the White Sox.”

12 McGraw, “The Right Stuff.”

13 Joe Lapointe, “NBC Covers All Bases on Morris’ No-hitter,” Detroit Free Press, April 8, 1984: 42.

14 Gage, “Morris’ Masterpiece.”

15 “Tigers’ Morris Hurls No-Hitter,” Detroit Free Press, April 8, 1984: 1.

16 McGraw, “The Right Stuff.”

17 Anne Tobik, “Carol Morris Worried Along With Her Husband,”Detroit Free Press, April 8, 1984: 42.

18 The other two were Virgil Trucks, who threw two no-hitters in 1952, and George Mullin in 1912. As of 2017, Justin Verlander has since thrown two no-hitters for Detroit (in 2007 and 2011), while Armando Galarraga was robbed of a perfect game in 2010 on a bad call on what would have been the final out.

19 Mooshil, “Morris No-hits the White Sox.”

20 Joe Falls, “Maturity 1st, Greatness 2nd for Morris,” Detroit News, April 8, 1984: 1C.

Additional Stats

Detroit Tigers 4

Chicago White Sox 0

Comiskey Park

Chicago, IL

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.