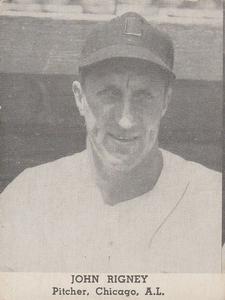

August 14, 1939: Chicago native Johnny Rigney pitches White Sox to historic win in first night game at Comiskey Park

On a warm August Monday night in Chicago, the sports news centered on baseball at Comiskey Park, where the White Sox would be playing their first night game at home. Afterward, the Chicago Tribune described the event: “In the inaugural of night major league baseball in Chicago more than 30,000 watched John D. Rigney of River Forest turn in a handsome three hit performance to beat the St. Louis Browns, 5 to 2.”1 Playing under the lights had been the ambition of J. Louis Comiskey, White Sox president-owner, but he had died a month before (July 18). Instead, “baseball under the stars was a hit from the moment young Charles Comiskey II [Louis’s son] pressed two switches at 8.25 o’clock that brought out the green in relief. It was as though one had suddenly walked into bright sunshine.”2

On a warm August Monday night in Chicago, the sports news centered on baseball at Comiskey Park, where the White Sox would be playing their first night game at home. Afterward, the Chicago Tribune described the event: “In the inaugural of night major league baseball in Chicago more than 30,000 watched John D. Rigney of River Forest turn in a handsome three hit performance to beat the St. Louis Browns, 5 to 2.”1 Playing under the lights had been the ambition of J. Louis Comiskey, White Sox president-owner, but he had died a month before (July 18). Instead, “baseball under the stars was a hit from the moment young Charles Comiskey II [Louis’s son] pressed two switches at 8.25 o’clock that brought out the green in relief. It was as though one had suddenly walked into bright sunshine.”2

The crowd3 was five to ten times bigger than in previous Chicago-St. Louis meetings in 1939 at Comiskey Park. In June, the first game of a three-game series between the two teams drew 3,000, while the next day’s doubleheader brought just 6,000 to the ballpark.

Chicago’s starter, 24-year-old Johnny Rigney, was in his third season with Chicago. He had his only winning season in 1939, and he brought a six-game winning streak into this contest against St. Louis. He was opposed by Bill Trotter, a 6-foot-2-inch righty for the Browns who had won four of his last five decisions.

The White Sox “started the scoring business in the second inning,”4 when Rip Radcliff hit a single to left with one out. Eric McNair flied out, and with Mike Tresh batting, Radcliff swiped second base. Tresh then knocked an RBI single to left, plating Radcliff with the game’s first tally.

With two outs in the bottom of the fourth, McNair launched a double to right-center. Tresh “sent McNair home with a single to center.”5 Rigney tried to help his own cause with a double, but Tresh stopped at third base. Both runners were stranded when Jackie Hayes hit a comebacker to Trotter for the third out.

An inning later, Chicago added another run. Joe Kuhel led off with a single to right. He stole second and then stopped at third when Mike Kreevich singled to center. Gee Walker hit a grounder that went off Trotter’s hand and beat the pitcher’s throw to first. Kuhel scored and Kreevich moved to second. Kreevich then stole third. Browns backstop Joe Glenn faked a throw toward third base but instead threw to first, as Walker had been lured off the bag by the fake. This put Walker in a rundown, during which Kreevich broke from third for home. St. Louis second baseman Johnny Berardino “threw to Glenn to harpoon Kreevich,”6 for the inning’s first out. Walker managed to get to second, but the White Sox would not score again in the inning.

Rigney, Chicago’s big right-hander, faced the minimum through the first five innings, fanning six. A leadoff walk to Glenn in the sixth ended the perfect game. Then Chicago shortstop Luke Appling had “an almost unprecedented fit of the fumbles.”7 Obviously affected by the lights, Appling botched three grounders and a catch, each of which could have resulted in a double play. Instead, Appling’s miscues resulted in two force outs and two errors, presenting the St. Louis squad with two runs “on a hit production of one single [by Berardino], the first hit off Rigney, some ten minutes after the inning should have been over.”8 Every one of the four balls hit into the infield during the top of the sixth was misplayed by Appling.

Chicago “pulled out of danger in the seventh.”9 With the score 3-2 and Roxie Lawson now pitching for the Browns, Kuhel singled and Kreevich doubled to start the action. Walker received an intentional pass, loading the bases. Appling forced Walker at second, with Kuhel scoring on the play. When Radcliff sent a grounder to second, Berardino fired home and Kreevich was declared out at the plate for the second time in the game. McNair then delivered a single to center, driving in Appling. The 5-2 score stood to the end.

The victory in the first night game at Comiskey Park “lighted the White Sox’ way right back into third place a half-game ahead of the Cleveland Indians.”10 Rigney earned his 10th victory of the season, and Chicago scored its ninth win against St. Louis in 11 games to this point of the season.11 Had Appling’s defense been a bit more solid, Rigney would have pitched a shutout; both of the runs scored in the sixth inning were unearned. As reported in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, “even the lights couldn’t help [the Browns] see Johnny Rigney’s fast one.”12 In the complete-game victory, his 10th of the season, Rigney struck out 10 Browns batters, scattering three hits with one walk. Trotter was saddled with the loss, his record dropping to 5-6.

It appeared that only Appling was affected by the new nighttime venue, although some players complained that “a ground ball makes a shadow as it skips across the turf, thus increasing the hazard of fielding.”13 Chicago’s skipper, Jimmy Dykes, told reporters, “The umpires still look the same to me under the lights.”

Four nights later, on August 18, the White Sox hosted the Cleveland Indians for the second home night game of the season. According to Retrosheet, 46,000 witnessed the White Sox’ 1-0 victory, as Eddie Smith beat Cleveland’s Bob Feller in 11 innings. Chicago played five night games at Comiskey Park in 1939, going 4-1 with a swarm of fans at each game. The only loss came on August 22, when the New York Yankees blasted the White Sox, 14-5, before a season-high crowd of 50,000. Johnny Rigney earned victories in three of the four night-game wins.

While the White Sox and Browns were making history at Comiskey Park on August 14, the two cities’ other teams (Cubs and Cardinals) played each other in a day game at Sportsman’s Park in St. Louis. The Cubs won, 4-0, extending their winning streak to five games. Members of the Cubs’ front office were in attendance at Comiskey for the White Sox’ historic event. Charles Drake, assistant to P.K. Wrigley, told reporters that “Wrigley Field would not be lighted until the Cubs were certain their fans wanted night baseball. He declared that under no circumstances would the Cubs join the night baseball movement next year [1940].”14 That certainty took another 49 years, as the lights didn’t go on at Wrigley Field until August 8, 1988, “breaking a 72-year tradition of sunshine baseball.”15 That game was rained out and the first official game was played the following night.

Sources

In addition to the sources mentioned in the Notes, the author consulted baseball-reference.com and retrosheet.org.

Notes

1 Edward Burns, “Sox Win 1st Night Game, 5-2, Before 35,000,” Chicago Tribune, August 15, 1939: 15.

2 Edward Prell, “Cub Officials See Sox Play Under Lights,” Chicago Tribune, August 15, 1939: 15.

3 The Chicago Tribune reported a crowd of 35,000. The St. Louis Post-Dispatch reported “slightly more than 30,000.” Both retrosheet.org and baseball-reference.com list the attendance as 30,000.

4 Burns.

5 Ibid.

6 Ibid.

7 Ibid.

8 Ibid.

9 Ibid.

10 Ibid.

11 The White Sox were 19-4 against the Browns in 1939.

12 “Browns Idle After Losing at Night in Chicago,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, August 15, 1939: 11.

13 Prell.

14 Ibid.

15 Jerome Holtzman, “Lights! Action! And then …,” Chicago Tribune, August 9, 1988: 37. The Cubs-Phillies game was rained out, delaying the first complete night game at Wrigley Field until the next night, August 9.

Additional Stats

Chicago White Sox 5

St. Louis Browns 2

Comiskey Park

Chicago, IL

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.