August 16, 1922: Chicago American Giants outlast New York Bacharach Giants in 20-inning pitchers’ duel

Harold Treadwell wasn’t the best pitcher on the 1922 New York Bacharach Giants roster. The submarining right-hander’s 6-9 won-lost record and 4.35 ERA against Negro League competition wasn’t outstanding, but he was one of the two most-used Bacharach hurlers on a mediocre team.1

Harold Treadwell wasn’t the best pitcher on the 1922 New York Bacharach Giants roster. The submarining right-hander’s 6-9 won-lost record and 4.35 ERA against Negro League competition wasn’t outstanding, but he was one of the two most-used Bacharach hurlers on a mediocre team.1

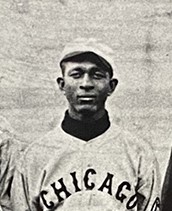

Dave Brown of the Chicago American Giants (13-3, 2.90) was among the best pitchers in the Negro Leagues at the time. The 25-year-old Texas-born left-hander was likely en route to being one of the best ever until he had to run from the law three years later.

On August 16, 1922, though, in the third season of the Negro National League (founded in 1920), they were both the stars of a 20-inning marathon at Chicago’s Schorling Park, the American Giants’ home. Treadwell, who had pitched a nine-inning complete-game win against Chicago three days before, went the whole long way for the Bacharachs. Brown, a little late to the party, came on in relief in the fifth. He had gone nine innings in a win against the New Yorkers only two days prior, then threw 16 innings of shutout relief. Brown was the winning pitcher when Treadwell finally weakened in the 20th, giving Chicago a 1-0 victory.

The American Giants were their usual winning selves that season, taking their third straight Negro National League pennant by a hair over the Kansas City Monarchs with a .607 winning percentage.2 The Bacharach Giants were associate members of the league, meaning they were encouraged to play regular league teams, all of which were based in the Midwest, and had their rosters protected from “raiding” by other league members, although they couldn’t compete for the league title.

They weren’t that successful against the NNL, however, with only a .448 winning percentage. The Bacharachs might have had a better record had the franchise not split in half in the spring due to an ownership wrangle. A second Giants squad, run in Atlantic City, kept star infielder Dick Lundy and other players who could have made a combined roster more formidable.

If the second inning of this marathon game was to be any example, scoring opportunities would present themselves in vain. For the Bacharachs, first baseman Robert Hudspeth and right fielder Frank Duncan singled off Chicago starter Ed Rile, putting runners on first and second with one out.

Then Treadwell singled to center with two outs, but the bases-loaded situation lasted only a few seconds. The lanky Hudspeth,3 rounding third and intent on scoring, observed Chicago right fielder Cristóbal Torriente’s dead-aim throw to the plate. He braked, retreated, and was out at third by 10 feet on catcher Jim Brown’s peg.4

Torriente made it to second in the bottom of the inning on a single and steal, but Bacharach third baseman Oliver Marcell helped kill any scoring chance with a “running catch of [shortstop Bobby] Williams’ foul off his shoes with his bare hand.”5

Treadwell, who gave up nine hits, walked seven, and hit two batters in his 19⅓ innings, was in some trouble on and off, but his 12 strikeouts and many harmless infield grounders and popups came at the right time to get out of innings.

He also had help from a poor choice by Dave Brown himself. In the bottom of the fifth, American Giants first baseman Leroy Grant hit a leadoff single and was forced at second on Brown’s grounder. But then right fielder Jelly Gardner reached first on Marcell’s error and second baseman Bingo DeMoss walked to load the bases. Jimmie Lyons, the left fielder, launched what looked like a run-scoring fly to his counterpart in left, Elias “Country” Brown. Country Brown nailed Dave Brown at the plate, and it was on to the sixth.

Lyons, described by Negro Leagues historian James Riley as “one of the fastest men ever to wear a baseball uniform,”6 figured in another failed Chicago attempt in the 17th. Using his famous wheels, he started the inning by beating out a slow roller and was sacrificed to second. He then “thrilled the crowd” by stealing third, but definitely didn’t please the Chicago fans an out later when he was caught stealing home.7 An unsuccessful steal also killed a Chicago rally in the 19th. Gardner had reached second via a walk and a hit batsman when catcher Julio Rojo threw him out at third on a steal attempt.

Riles had given up a leadoff hit in the top of the fifth, the fourth he had yielded along with a walk and a hit batsman. The reason for Chicago manager Rube Foster’s decision is lost to history, but Foster brought Brown in with no outs. From there Brown was spectacular – in 16 innings he struck out 10 and walked only two. He faced only six batters above the minimum, assisted by two double plays and a Bacharach miscue in the 12th when Country Brown left second base too early on a fly ball to right and was called out on an appeal play.

The 18th was almost Brown’s undoing, though. He had cruised through the previous three innings, nine up and nine down, when Hudspeth led off with his second single of the game. Then Rojo was hit on the arm by a pitch. An infield out and a fly out later, Treadwell “dumped one in front of the plate and beat it out to first.”8

Faced with a bases-loaded, two-out dilemma, Brown seemed to emulate the behavior of his boss when Foster had been an ace pitcher. (In an essay on “How to Pitch,” Foster wrote “do not worry” with runners on the sacks: “I have often smiled with the bases loaded.”)9 Smiling or not, Brown coolly struck out center fielder George Shively.

The players were playing as hard as they could but scoring no runs. Perhaps the razor-sharp baseball mind of Chicago’s Foster subtly made the difference in the end.

Chicago Defender sports editor Fay Young, doubling as official scorer, was sitting on the American Giants’ bench next to Rube when Duncan got his third single of the game in the top of the 10th and Bacharachs manager John Henry Lloyd sent Ramiro Ramirez to run for him and then take his place in the field.

Foster, taking in the Bacharachs’ warmups before the bottom of the inning, turned to Young and observed that the new right fielder “hasn’t the best throwing arm in the world.”

Ramirez was still still out in right when the bottom of the 20th began. Torriente worked Treadwell for a walk and moved to second on Williams’s sacrifice. This brought up Dave Malarcher, the Americans’ third baseman. In a retrospective column in 1948 Young said that Foster wanted his batter to hit to right: “Rube got up off the bench and yelled to Dave ‘just meet it’, and that’s exactly what he did. He dumped one into right field. It was a hit.”11

Ramirez was a good fielder, and he scooped the ball on one bounce and fired home. But the throw was a little wide, and Torriente scored.

“[M]any fans” [at least the Defender sportswriter, probably Young himself, did] – “believed if Duncan had stayed in the game Torrienti would never have scored and the clubs would have battled on until darkness.” 12 Even after 20 innings, though, darkness was nowhere in sight. The entire game took only 3 hours and 38 minutes.13

Harold Treadwell continued his Negro League career through most of the rest of the decade, coincidentally wrapping up in 1928 with the American Giants.

By then Dave Brown had disappeared, following a murder in Harlem in 1925. The Bacharachs by then had reconsolidated in Atlantic City, and with five other Eastern Seaboard teams had formed the Eastern Colored League to challenge the NNL in 1923. The ECL teams gave up roster-raiding protection from the NNL, but also felt free to entice players from the other league.

Thus, Brown became the ace hurler for New York City’s Lincoln Giants. He began 1925 by defeating the Bacharachs again on Opening Day, and then went on a multiday gambling and drinking bender with a couple of teammates. The good times ended at 3:25 A.M. on April 28 when a street confrontation with a man named Benjamin Adair turned violent. Adair drew his pistol, but Brown had one, too. According to the police Brown, as on the mound, was fast, and his aim was true.

Brown and his two mates caught a taxi and left the scene. The two other Lincolns, Oliver Marcell and pitcher Frank Wickware, were soon interviewed by police, but released from custody. Brown, however, left New York, where he was officially wanted for murder. It seems he pitched semipro ball in the Midwest for several years, known as Bill “Lefty” Wilson. Several current or former Negro Leaguers played against him there, but no one ever ratted him out.

He moved to North Carolina, where he lived under his given name and was picked up by the police there in 1938 for the New York case. But time had gone by, none of the witnesses to the shooting could be found, and New York authorities were no longer interested in him.14

Brown was 63-24 with a 2.46 career ERA in the Negro Leagues when he went on the lam.

Acknowledgements

This article was fact-checked by Kevin Larkin and copy-edited by Len Levin. Tom Thress of Retrosheet.org helpfully provided the 1948 Chicago Defender article referenced in the article.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted the Seamheads.com Negro League Database website and Retrosheet. org for individual and team statistics. In addition, “American Giants Even up the Count with N.Y. Bacharachs” in the Chicago Defender of August 19, 1922, page 10, provided additional information on the American Giants-Bacharach Giants series leading up to this game.

Notes

1 Treadwell’s fellow workhorse was Dick “Cannonball” Redding, a Hall of Fame nominee and included on many all-time Negro League teams. Treadwell is recorded as having one more start and nine more innings pitched in 1922, both accounted for by this single game.

2 When all games against Negro League-level competition are taken into account (this game, for example), Chicago was slightly outplayed by the Monarchs and Indianapolis ABCs. Among the NNL championship teams, though, they were first.

3 “The huge first baseman is considered the largest man in semi-pro baseball,” a New Jersey newspaper observed of Hudspeth in 1925. “Hudspeth is a star if there ever was one. He can field his position exceptionally well in spite of his length – he measures some good six feet eight inches above the ground.” “Carl Deetgen Will Twirl in Twilight Game for Madonnas,” Bergen (New Jersey) Evening Record, July 29, 1925: 17.

4 “Record Game to American Giants, 1 to 0,” Chicago Defender, August 26, 1922: 10.

5 “Record Game to American Giants, 1 to 0.”

6 James A. Riley, The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues (New York: Carroll & Graf, 1994), 500.

7 “The Game Play by Play,” Chicago Defender, August 26, 1922: 10.

8 “The Game Play by Play.”

9 Andrew Foster, “How to Pitch,” in Sol White’s History of Colored Baseball, with Other Documents on the Early Black Game, 1886-1936, Jerry Malloy, ed. (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1995), 96-100.

10 Fay Young, “Foxy Rube Foster’s Order to Dave Malarcher Broke Up 20-Inning Game 26 years ago, 1-0,” Chicago Defender, September 4, 1948: 11.

11 Young, “Foxy Rube Foster’s Order.”

12 “Record Game to American Giants, 1 to 0.”

13 “The Game Play by Play.”

14 Frederick C. Bush, “Dave Brown,” SABR Baseball Biography Project, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/dave-brown-2/.

Additional Stats

Chicago American Giants 1

New York Bacharach Giants 0

20 innings

Schorling Park

Chicago, IL

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.