August 22, 1912: Honus Wagner hits for the cycle, but Pirates fall to Giants

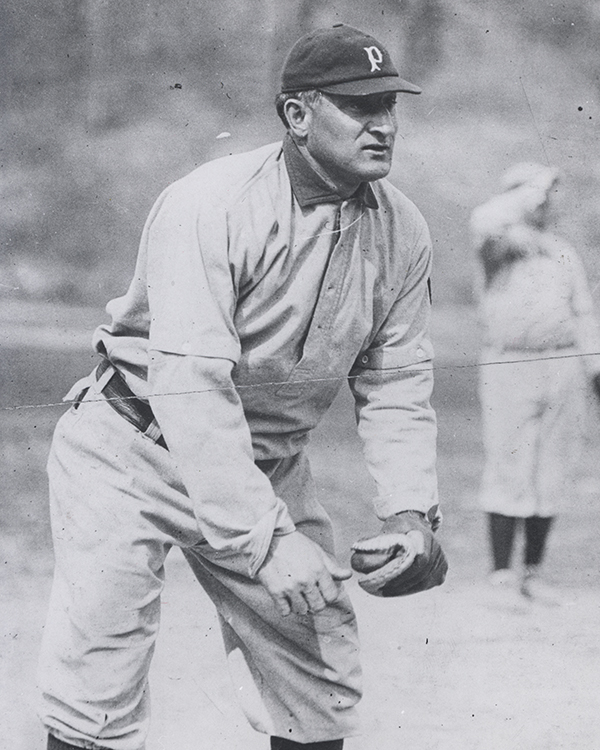

Before a sold-out and boisterous Forbes Field crowdi , future Hall of Famer Honus Wagner “had his bat working overtime,”2 producing seven hits (in two games) as his Pittsburgh Pirates split a doubleheader with the visiting New York Giants. About 25,000 were on hand to witness the pair of contests.3 In the opener, Wagner had two singles, a double, and a stolen base, and he scored two of his team’s runs, ensuring that Pittsburgh edged past the Giants, 3-2. Howard Camnitz outdueled New York ace Christy Mathewson, holding “the Gotham gang to half a dozen hits.”4 In the second game, Wagner accomplished the rare feat of hitting for the cycle, unfortunately in a losing cause.

Before a sold-out and boisterous Forbes Field crowdi , future Hall of Famer Honus Wagner “had his bat working overtime,”2 producing seven hits (in two games) as his Pittsburgh Pirates split a doubleheader with the visiting New York Giants. About 25,000 were on hand to witness the pair of contests.3 In the opener, Wagner had two singles, a double, and a stolen base, and he scored two of his team’s runs, ensuring that Pittsburgh edged past the Giants, 3-2. Howard Camnitz outdueled New York ace Christy Mathewson, holding “the Gotham gang to half a dozen hits.”4 In the second game, Wagner accomplished the rare feat of hitting for the cycle, unfortunately in a losing cause.

Despite banging out 16 hits in the second contest, the Pirates could not beat New York’s Rube Marquard, who tossed a complete game to secure his 25th win of the season. The left-handed-throwing Marquard had won his first 19 starts of the season before losing to the Chicago Cubs on July 8. His confidence was high each time he took the ball. His opponent on the mound was Pittsburgh right-hander Claude Hendrix, who “suffered a bombardment in the first four innings.”5 From July 4 through August 14, Hendrix had 11 straight starts of at least eight innings, but in his last starting effort before this game, he had been knocked out after three innings and was used out of the bullpen once; for four innings two days earlier.

Pittsburgh started the action in the bottom of the first inning, as leadoff batter Solly Hofman doubled down the right-field line and scored on a single by Wagner. The Flying Dutchman promptly stole second base, his second steal of the day, but Dots Miller grounded out to pitcher Marquard to end the threat.

In the top of the second, New York’s Red Murray led off with a triple, and scored on a double down the right-field line by Fred Merkle. After Buck Herzog sacrificed Merkle to third, Chief Meyers followed with a single, but Merkle did not score. So with Art Fletcher batting, Giants manager John McGraw put on the double steal. Pirates catcher George Gibson threw the ball into center field trying to get Meyers at second, and the error allowed Merkle to motor home. Merkle was credited with a stolen base as well. The Giants now led, 2-1.

In the fourth inning, Herzog tripled, Meyers singled, and Fletcher tripled, and New York had two more tallies to make the score 4-1. In the fifth inning, Pirates skipper Fred Clarke replaced Hendrix with Ed Warner, a rookie left-hander. Hendrix had yielded seven hits to the 19 batters he faced. Warner would also face 19 batters and give up four runs.

In the sixth inning, each team scored once. New York manufactured its run when Herzog was hit by a pitch, motored to third on a single by Meyers, and scored on a fielder’s choice when Fletcher grounded to Wagner, who forced Meyers at second. “The Corsairs got this run back”6 when Wagner led off with a triple to the fence in left-center. He trotted home when Miller singled up the middle to cut the Giants’ advantage to 5-2. Then, in the bottom of the seventh, Pittsburgh struck again as Hofman singled to right, followed by Max Carey, who lifted a fly ball down the left-field line that dropped in for a double as New York’s Fred Snodgrass, who had raced over to make a shoestring catch, instead saw the ball slip through his fingers. Hofman halted at third. Snodgrass insisted that the ball had landed foul, but umpire Bill Klem, from home plate, “declared it safe.”7 Wagner drove a ball to center, and this time it was Beals Becker who couldn’t make the play, and the ball dropped in. This double enabled Wagner to trade places with Carey, who scored behind Hofman. Miller then singled again, and “Wagner carried the tying run across the pan.”8 The score was now tied at 5-5.

Four New York hits resulted in three more runs in the Giants’ half of the eighth. With one out, Herzog singled. Meyers doubled him home, and then scored on Marquard’s single into center field. Snodgrass drove a triple to deep left, and “Marquard waltzed home.”9 Pittsburgh manager Clarke called on right-hander King Cole to pitch the ninth, and Cole retired the Giants in order.

The Pirates tried to mount a two-out rally in the ninth. According to the Pittsburgh Daily Post, “Wagner sailed the sphere over the left field fence above the twelfth panel, but nobody was on when it happened and the jig was up.”10 Miller, who was 3-for-5 in the game, came up next and doubled to center, but he was stranded as Alex McCarthy, pinch-hitting for Chief Wilson, flied out to Larry Doyle past second base for the final out of the game. The Giants had won, 8-6.

TheNew York Timesdescribed Wagner’s performance with great praise. His “quartet of hits figured in every Pittsburgh run, three being scored by the Teuton and the other three chased home by his timely smashes. On the paths he showed that Father Time is still a stranger by stealing two bases, and in the field he galloped nimbly on all sides of his position, accepting fourteen chances out of a possible fifteen.”11 In the last four innings of the tight second game, the 38-year-old Wagner had come to bat three times, and produced a triple, double, and home run.

Of the 29 hits between the two squads, 13 went for extra bases. Wagner hit the only home run, but there were five triples and seven doubles. The distances to the fences in left, center, and right field were 360 feet, 462 feet, and 376 feet, respectively,12 so the spacious stadium allowed for extra-base hits. In the cycle, Wagner was 4-for-5 and added a stolen base. His fifth home run of the season instantly became “the longest over-the-fence home run ever poled at Forbes Field.”13 The game was “an old-fashioned slugging bee, with doubles and triples coming so fast that the outfielders were legweary from chasing the ball.”14 In addition to Wagner’s four safeties, Pittsburgh’s Hofman, Carey, and Miller each had three hits in the losing effort. Gibson and Warner were the only other Pittsburgh players to get hits.

For Pittsburgh, Hendrix and Warner combined to allow eight earned runs to the Giants; Cole pitched one scoreless inning. Warner picked up the loss, the only loss of his major-league career.15 Every New York batter except Becker got at least one hit. Meyers had the most productive day for New York, going 4-for-4 with two runs scored and two batted in. Five different New Yorkers pushed runs across home plate.

At the end of the day, the Giants stood at 78-33, atop the National League, while the third-place Pirates had a record of 67-45. In the first two weeks of September, the Pirates won 12 games in a row, but remained mired in third. After September 2, they went 21-5, finally climbing to second by the season’s last week. They ended the campaign with a sterling record of 93-58-2, but 10 games behind New York.

New York fans might have been disappointed, as McGraw used his two aces, Mathewson and Marquard, and his Giants lost a half-game in the standings to the second-place Cubs, who were now four games behind. The Giants had been alone in first place since May 21, due to three nine-game winning streaks and another of 16 games, which carried through to July 3. McGraw’s team finished at 103-48-3, taking the second of three consecutive National League pennants.

Wagner’s cycle was the fifth in Pittsburgh franchise history. Fred Carroll had the first, on May 2, 1887. Player-manager Clarkecycled on July 23, 1901, and again on May 7, 1903. Chief Wilson accomplished the rare feat on July 3, 1910. After Wagner’s accomplishment, Pirates fans would have to wait nine years before Dave Robertson hit for the cycle on August 30, 1921. From Fred Carroll (May 2, 1887) to John Jaso (September 28, 2016), 24 Pirates have hit for the cycle, the most of any major-league team, as of the beginning of the 2017 season.

This article appears in “Moments of Joy and Heartbreak: 66 Significant Episodes in the History of the Pittsburgh Pirates” (SABR, 2018), edited by Jorge Iber and Bill Nowlin. To read more stories from this book at the SABR Games Project, click here.

Sources

https://www.baseball-reference.com/boxes/PIT/PIT191208222.shtml

http://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1912/B08222PIT1912.htm

Notes

1 Ed F. Balinger, “Buccaneers and Giants Break Even in Bargain on Forbes Field,” Pittsburgh Daily Post, August 23, 1912: 13.

2 Ibid.

3 Retrosheet lists the attendance at 25,000. The Pittsburgh Daily Postproclaimed 20,000 fans, the New York Timeslisted 27,000 spectators, but the Pittsburgh Post-Gazetterecorded 25,000. According to Forbes Field: Essays and Memories of the Pirates’ Historic Ballpark, 1909-1971, the stadium capacity was 25,000. See David Cicotello and Angelo J. Louisa, Forbes Field: Essays and Memories of the Pirates’ Historic Ballpark, 1909-1971(Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2007).

4 Balinger.

5 James Jerpe, “Wagner and Camnitz Star While Pirates and Giants Draw Even,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, August 23, 1912: 8.

6 Balinger: 14.

7 Ibid. In 1912, only two umpires worked the game. Klem was behind home plate and Jim Johnstone worked first base.

8 Ibid.

9 Ibid. Marquard was a decent hitter, sporting a .215 average at this point in the season. In 1912, he had 10 runs batted in, helping his cause on the mound.

10 Balinger: 13.

11 “Giants Divide With Pirates,” New York Times, August 23, 1912: 7.

12 Michael Gershman. Diamonds: The Evolution of the Ballpark(Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2003), 90.

13 Jerpe. Forbes Field opened in 1909, so it had been home to the Pirates for just three seasons.

14 New York Times.

15 Warner’s major-league career lasted for two months.He appeared in 11 games in 1912, starting three. He got one victory, a shutout of the Boston Braves.

Additional Stats

New York Giants 8

Pittsburgh Pirates 6

Game 2, DH

Forbes Field

Pittsburgh, PA

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.