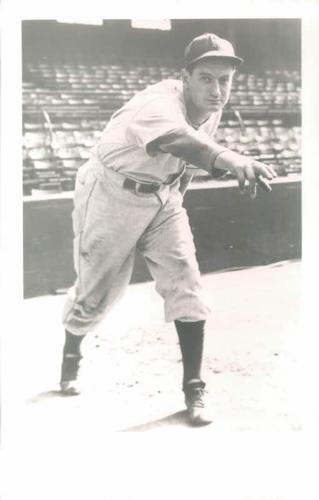

July 10, 1947: Don Black pitches first no-hitter at Cleveland Stadium

Don Black reached the end of the line in Philadelphia. A’s manager Connie Mack was a patient man. But the Tall Tactician had his limits. For Don Black was an alcoholic. It was a disease that Black could not control, and like all diseases, there were residual effects that were equally damaging.

Don Black reached the end of the line in Philadelphia. A’s manager Connie Mack was a patient man. But the Tall Tactician had his limits. For Don Black was an alcoholic. It was a disease that Black could not control, and like all diseases, there were residual effects that were equally damaging.

Black showed promise in the minor leagues. He posted excellent records, and hurled two no-hitters. The first was on July 22, 1941, a 1-0 win over the Staunton Presidents. Black’s second no-hitter occurred on August 4, 1942, a 4-0 victory over the Pulaski Counts. Based on his fine performance, Mack paid $5,000 for his services. He was added to the A’s mound staff, and showed some promise. In his fourth career start, he threw a one-hitter against the St. Louis Browns at Shibe Park on May 30, 1943. But the remainder of his season was not exactly earth-shattering; Black (6-16, 4.20 ERA) made 26 starts and totaled 12 complete games.

Mack more than once took the fatherly approach with some of his players. Especially with those players who were going through difficult times away from the diamond. It was one of the reasons for his popularity. If anything, he gave Black multiple chances when the talk of his hitting the bottle became common knowledge in the clubhouse. Mack was no fool. In five decades of professional baseball, he had seen it all.

Black’s tenure came to a head in Boston on June 5, 1945. At the Somerset Hotel, Black joined Dick Siebert, Al Simmons, and Charlie Metro for breakfast. Black ordered a bowl of split pea soup. “We’re eating our eggs and he’s fumbling with the spoon to eat his soup,” said Metro, “and Simmons moves over a little to block Mr. Mack’s view of what’s going on, and the guy leans over to spoon up some soup and falls face down right into the bowl. We’re all moving in close to try to cover it up and Connie Mack says, ‘You don’t have to do that. I’ve seen it.’”1

Mack suspended Black for 30 days. The reason given was that Black broke “training regulations.” And although he returned to the A’s in early July, his destiny had already been decided by Mack. Black did take his place in the A’s pitching rotation. But his 4-8 record after the suspension yielded a 4.22 ERA.

Mack traded Black to Cleveland for an unannounced sum in October 1945. “He should be a great pitcher, but he’s a bad boy,” said Mack.2 In writing about the deal, the Philadelphia Inquirer mentioned that Black did not measure up in his potential with the Athletics and that he was often wild. In three seasons with Philadelphia, Black walked 254 batters in 510 2/3 innings while striking out 194.

“That fellow is a good pitcher, and I could use him,” said Indians skipper Lou Boudreau.3 But Black started only four games for Cleveland in 1946. He was optioned to Milwaukee of the American Association for the balance of the season.

Cleveland had the foundation for a good pitching staff in 1947. Bob Feller led the league in wins (20) and strikeouts (196). Bob Lemon was transitioning to the pitching mound from center field and would pitch the first of seven 20-win seasons in 1948.

“Don Black should be a leading candidate for one of our starting jobs,” said Boudreau. “Everyone knows he belongs in the major leagues. We’ll certainly give him the chance to stay there.”4

The confidence Boudreau expressed did wonders for Black, who was having his best season thus far in the big leagues. He was the starting pitcher in the first game of a doubleheader against Philadelphia on July 10, 1947. Black’s record was 6-5 with a 3.84 ERA. The A’s countered with spot starter Bill McCahan (1-1, 4.35 ERA). The Indians and A’s were in fourth and fifth place of the American League standings, both double-digit games behind front-runner New York.

The ballgame was interrupted by a sudden downpour between the top and bottom half of the second inning. When play resumed 45 minutes later, the Indians scored three runs. Jim Hegan, George Metkovich, and Black each knocked in a run. Black’s RBI came on a sacrifice bunt. And although he also had two hits, it was Black’s work on the mound that got the most notice. For Black outhit the entire Athletics team as he tossed the first no-hitter ever at Cleveland Stadium. The 3-0 victory was witnessed by 47,871 fans.

Black was far from dominating, as he walked six while striking out five. But he was just good enough to earn the no-no. In fact, the game started off a bit rocky as Black threw eight wide ones at the outset, giving consecutive walks to Eddie Joost and Barney McCosky. After a groundout by Ferris Fain, Joost moved up to third base, and that was as far as any A’s baserunner would advance.

“He really had it tonight,” said Boudreau. “I went over in the seventh when he walked Fain to tell him to slow down a little. We all knew he was going for the no-hitter.”5

Mack was more thrilled for Black the man than for Black the baseball pitcher. “As we didn’t make any runs, I’m pleased that Don was able to pitch a no-hitter,” he said. “Our boys said his slider was working wonderfully — that’s why he was so successful. I was especially glad for Don because — well, you know he’s taking better care of himself these days.”6

One of the reasons Black was taking better care of himself was because of Bill Veeck. The Cleveland owner absorbed a debt of $1,500 that Black had borrowed against the club. Veeck, a recovering alcoholic himself, suggested that Black join Alcoholics Anonymous. “Listen, give this thing a good try,” he told Black. “You won’t have to worry about your debts. I’m paying them all off. The only man you’re going to owe is me, and I’m not going to be tough on you.”7

Black’s career came to an untimely end the following season. He was at bat in the second inning of a game against the St. Louis Browns on September 13, 1948. He fell to the ground, collapsing with a cerebral hemorrhage. The hemorrhage in the blood vessel was caused by an aneurism, causing blood to run into the spinal fluid. His brain and his spinal column were bathed in blood. Although he made a full recovery, Black never pitched again.

Nine days after the collapse, Veeck, ever the showman, held a “Don Black Day” at Cleveland Stadium on September 22 before a game against Boston. The game was switched from an afternoon affair to a nighttime start. Boston manager Joe McCarthy balked at the switch, as Feller was on the mound for Cleveland and the Red Sox would rather face him in the afternoon light. But the game went on and Cleveland won 5-2 to pull even with Boston in the AL pennant race.

Black’s teammates paid their way into the park as a sign of solidarity for the fallen pitcher. They walked through the turnstiles in full uniform, purchasing a ticket as they entered. All of the gate’s receipts went to the cause for Black. A total attendance of 76,772 brought in more than $40,000. After Cleveland won the World Series, Black also received a full share of the team’s winning pot, which came to $6,970.

Sources

Besides the sources cited in the Notes, the author accessed Baseball-Reference.com for box scores/play-by-play information (baseball-reference.com/boxes/CLE/CLE194707101.shtml) and other data, as well as Retrosheet (retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1947/B07101CLE1947.htm).

Notes

1 Norman Macht, Connie Mack: The Grand Old Man of Baseball (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2015), 324.

2 Tony Lariccia, “Frayed and Forgotten,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, July 8, 2017: S3.

3 Ibid.

4 Lariccia: S4.

5 Charles Heaton, “Don Knew He Had No-Hitter on Fire,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, July 11, 1947: 15.

6 Ibid.

7 Lariccia: S4.

Additional Stats

Cleveland Indians 3

Philadelphia Athletics 0

Cleveland Stadium

Cleveland, OH

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.